Abstract

The persistence, and international expansion, of food banks as a non-governmental response to households experiencing food insecurity has been decried as an indicator of unacceptable levels of poverty in the countries in which they operate. In 1998, Poppendieck published a book, Sweet charity: emergency food and the end of entitlement, which has endured as an influential critique of food banks. Sweet charity‘s food bank critique is succinctly synthesized as encompassing seven deadly “ins” (1) inaccessibility, (2) inadequacy, (3) inappropriateness, (4) indignity, (5) inefficiency, (6) insufficiency, and (7) instability. The purpose of this paper is to examine if and how the contemporary food bank critique differs from Sweet charity’s “ins” as a strategy for the formulation of synthesizing arguments for policy advocacy. We used critical interpretive synthesis methodology to identify relationships within and/or between existing critiques in the peer-reviewed literature as a means to create “‘synthetic constructs’ (new constructs generated through synthesis)” of circulating critiques. We analyzed 33 articles on food banks published since Sweet charity, with the “ins” as a starting point for coding. We found that the list of original “ins” related primarily to food bank operations has been consolidated over time. We found additional “ins” that extend the food bank critique beyond operations (ineffectiveness, inequality, institutionalization, invalidation of entitlements, invisibility). No synthetic construct emerged linking the critique of operational challenges facing food banks with one that suggests that food banks may be perpetuating inequity, posing a challenge for mutually supportive policy advocacy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Food banks, where recipients obtain donated food items directly from a charitable organization for preparation and consumption elsewhere, have been in existence for at least three decades in Canada, the United States (US), Australia and New Zealand. They are becoming well established in other high-income countries such as the United Kingdom (UK), Germany, and the Netherlands.Footnote 1

For many members of the public, food banks are familiar as a societal response to poverty. It has also been argued that the existence of food banks signals government failure to provide adequate social welfare and nutrition safety nets for vulnerable citizens—despite the commitments of 185 countries at the 1996 World Food Summit in Rome, during which almost 10,000 participants discussed measures to eradicate hunger both within and across member countries. The Rome Declaration committed governments, in partnership with civil society, to “ensur[ing] an enabling political, social, and economic environment designed to create the best conditions for the eradication of poverty” and in Article 20, Objective 2.2, item (c), to “Develop within available resources well-targeted social welfare and nutrition safety nets to meet the needs of the food insecure, particularly needy people, children, and the infirm” (Food and Agricultural Organization 1996).

In 1998, Poppendieck published a book, Sweet charity: emergency food and the end of entitlement (Sweet charity), based on her critical analysis of data accumulated on emergency food programs from across the US. These programs included food pantries (see below for the American distinction been a food bank and food pantry). The book has endured as an influential critique. Poppendieck (1998) synthesized the food bank critique succinctly as encompassing seven deadly “ins”: (1) inaccessibility, (2) inadequacy, (3) inappropriateness, (4) indignity, (5) inefficiency, (6) instability, and (7) insufficiency.Footnote 2 These “ins” speak primarily to concerns related to food bank operations.

In 20 years of academic writing about food banks since the World Food Summit and the publication of Sweet charity, has the food bank critique changed, and why is this question important? Academic writing is intended to add theoretical, methodological, and empirical insights into topics of societal importance. Academics have been increasingly called upon to mobilize knowledge (Tetroe et al. 2008). In the public policy arena this means producing policy-relevant knowledge that can be disseminated in forms that support evidence-based action (Adily et al. 2009; Elliott and Popay 2000; Tetroe et al. 2008). Knowledge mobilization typically requires precise language and concepts, in order to be used effectively in policy advocacy efforts directed towards specific audiences (Entwhistle et al. 2012). For some research topics, knowledge has converged over time. In other areas, a breadth of academic literature exists, with its various ideas, debates, and theories (i.e. constructs) that requires integration—also referred to as knowledge synthesis—so that the topic as a whole can be understood, and the body of knowledge mobilized toward action.

In 2006, Mary Dixon-Woods and colleagues published a new methodological approach—critical interpretive synthesis, which is directed at synthesizing a diverse literature on a topic in order to create conceptual clarity. Critical interpretive synthesis was envisioned as an alternative to focused qualitative approaches such as meta-ethnography or focused quantitative approaches such as traditional systematic reviews in the health field, designed to synthesize a body of literature comprised of diverse ideas, methods, and approaches. Critical interpretive synthesis methodology has been further explained as an approach that identifies relationships within and/or between existing constructs (ideas or theories containing various conceptual elements) in the literature as a means to create “‘synthetic constructs’ (new constructs generated through synthesis)” (Entwhistle et al. 2012, p. 71). For example, in their original article on critical interpretive synthesis, Dixon-Woods et al. analyzed the example of health care access for vulnerable groups. In their synthesis, they paid particular attention to divergent constructs in the literature and concluded that “access” itself had been inconsistently operationalized across the field. The dominant construct of access was various measures of “utilization.” When diverse ways of understanding access for vulnerable groups were integrated, the researchers arrived at the synthetic construct of “candidacy” which they defined as the way in which people’s eligibility for medical attention and intervention is jointly negotiated between individuals and health services (Dixon-Woods et al. 2006).

The purpose of this paper is to take stock of and synthesize the academic literature within the context of a growth in real-world prevalence of food banks. By examining if and how the contemporary food bank critique differs from Sweet charity’s “ins,” formulated nearly two decades ago, our aim is to produce a solid starting point for academics today wishing to formulate synthesizing arguments for policy advocacy. We use critical interpretive synthesis methodology to consider the constructs underlying the circulating food bank critiques as presented in the academic literature. Our intent is to arrive at a synthetic construct that will support knowledge mobilization efforts for policy advocacy around food banks that is applicable to a growing array of countries in which food banks operate.

Situating food banks

At the beginning of this article, we defined the term food bank as distinct from programs where prepared meals are provided to recipients. The terminology of the food bank varies by country and region. For example, in the US, food is stored in a large central food bank and given to clients locally at a food pantry (Poppendieck 1998). Food hampers are given out in Canada directly to individuals from smaller food banks (Willows and Au 2006). In the UK, a registered franchise known as the Foodbank gives out food parcels (Lambie-Mumford 2013).

We would be remiss if we did not state clearly that food banks are a high-income country response to food insecurity, also referred to as food poverty in the UK, which is defined as income-related lack of access to nutritionally adequate and safe foods or the inability to obtain such foods in socially acceptable ways (Anderson 1990, p. 1560). The governmental measure of food insecurity that uses this definition is the United States Department of Agriculture-developed Household Food Security Survey Module, which is the standard metric used in national household surveys in Canada and the United States (Nord et al. 2008).

We should also emphasize that although we examine Poppendieck’s (1998) Sweet charity as a seminal critique on food banks that has helped to popularize the notion that food bank operations are challenged to adequately respond to households experiencing food insecurity, Poppendieck herself has continued a distinguished career and explored other food system issues. The whole of this academic body of work is beyond the scope of this article (http://www.hunter.cuny.edu/sociology/faculty/janet-poppendieck). Other scholars, in publications preceding Sweet charity or contemporary to its publication, have also appraised food banks with critiques of inappropriateness or that they represent an institutionalized response to food insecurity (e.g. Berry 1984; Curtis 1997; Husbands 1999; Lipsky and Thibodeau 1988; Riches 1986; Tarasuk and MacLean 1990). 14 years before Sweet charity, Berry, for example, critiqued food banks as a distraction to advocacy around program cuts:

“[It] is difficult to convince people that food banks are a step backwards because they seem to combine humanitarianism with good common sense. What can be wrong with taking surplus food out of warehouses and putting it into the mouths of the hungry? What is wrong is that food banks distract attention away from programs that work and thus reduce the pressure on government to stop cutting those same programs” (Berry 1984, p. 151).

Thus, the food bank critique was not originated by Poppendieck; however, her critique embodied in the seven deadly “ins” is the most enduring as illustrated by the potency of Sweet charity used in the title of a paper by Wakefield et al. 2013.

Food banks have long been regarded as emblematic of policy inadequacy to deal with poverty, and remain so today. Olivier De Schutter, the United Nations’ Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food, reiterated in his 2012 mission to Canada, “The reliance on food banks is symptomatic of a broken social protection system and the failure of the State to meet its obligations to its people” (De Schutter 2012, p. 5). Although food bank volunteers are well-regarded in society (Tarasuk and Eakin 2003), academics, policy commentators, and food bank volunteers alike have pointed to the existence of food banks as an indicator of the state’s failure to implement and support social policies that are meant to ensure a minimum standard of living (Lorenz 2012; Riches 1996, 1997, 2002; Rock 2006).

Quite apart from the examination of food bank use as an indictment of weak policy attention to poverty alleviation, the nutritional vulnerability of food bank clients has also been of concern since it was first raised by the nutrition and dietetic community. We trace the origin of this area of inquiry to 1988, when Campbell (an American nutrition researcher) and colleagues (two Canadian nutrition professionals) published a feature article in the Journal of the Canadian Dietetics Association that urged nutrition and dietetic professionals to reformulate the “hunger issue” in a way that could be operationalized within their scope of practice as nutrition experts:

Given that dietitian/nutritionists have justification for involvement in the hunger issue, yet few are involved, some re-formulation of the issue is essential to identify the roles they can play in the elimination of hunger in Canada. To create a constructive action agenda, a positively stated goal is very helpful. Therefore, it is proposed that (1) the goal of eliminating hunger can be reformulated to the creation of food security; and (2) delineation of the characteristics of food security will provide a framework within which to identify constructive action alternatives for nutrition professionals. (Campbell et al. 1988, p. 232)

Following this feature article and the subsequent publication of professional position papers on hunger and food insecurity (American Dietetic Association 1990; Canadian Dietetic Association 1991), concerns regarding the nutritional vulnerability of those attending food banks became a subsequent focus of nutrition-related food insecurity research. Indeed, Tarasuk and Davis suggested:

It is important to recognize that the way a problem gets defined or typified shapes responses to it. It could be argued that the community-based responses described here reflect a typification of the problem of poverty as a food problem—conceptualized either in terms of hunger or as failing under the broader rubric of food insecurity. Naming the problem in this way has framed responses to it and has been influential in shaping the involvement of nutritionists in these initiatives. (Tarasuk and Davis 1996, p. 73)

Accordingly, some scholars have argued that attention to nutritional vulnerability may have played a role in shifting the food bank away from factors precipitating income-related food insecurity and towards dietetic professional concerns regarding the nutritional quality of emergency food (e.g. Campbell 1991; Jacobs Starkey and Lindhorst 1996; Kennedy et al. 1992; Willows and Au 2006; Irwin et al. 2007).

Despite longstanding concerns directed at the rise in food banks in response to increasing rates of poverty and food insecurity, nearly 30 years later, food banks have become the de facto way of both addressing and publicly characterizing food insecurity in Canada (Riches 2011). In March 2014, HungerCount (an annual cross sectional survey of food bank use across the country) reported that its count of emergency food program users for the month was 841,191 or 2.4 % of the total Canadian population, a 24.5 % increase in food bank use since 2008 (Food Banks Canada 2014). In the US, food banks are seen as an integral component of the “private food assistance network” and not “emergency food assistance … a misnomer because the term suggests a short-term, acute reliance on the network” (Daponte and Bade 2006, p. 669). The Hunger in America 2014 study, based on food bank provider data, reported 46.5 million recipients in the United States who were served through 58,000 food pantries and affiliated programs (Feeding America 2014). In the UK, the Trussell Trust Foodbank Network is premised on the notion that “every town should have a Foodbank” (Lambie-Mumford 2013, p. 79). Indeed, Trussell Trust Foodbanks increased from 29 in 2009–2010 to 251 in 2013–2014 (Loopstra et al. 2015).

Today, despite widespread agreement that food banks do not solve the problem of income-related food insecurity in high-income countries, the policy discourse on food banks appears to encompass diverse issues, approaches, and perspectives. We posited that the contemporary food bank critique could be discerned from a new knowledge synthesis of the peer-reviewed literature on food banks since Sweet charity, and by employing a synthesis methodology that could make sense of diverse constructs underlying different academic perspectives. In doing so, we found that the list of original “ins” related to food bank operations has been consolidated over time. We also found additional “ins” that extend the food bank critique beyond primarily an operations focus. The constructs subsuming these new “ins” however, did not yield a synthetic construct linking the original with the new. In fact, the lack of a contemporary food bank critique that is based on conceptual coherence may well explain policy advocacy conflicts which on the one hand seek to improve food bank operations, and on the other hand construe food banks as themselves a vehicle for the perpetuation of inequity and thus a barrier to those advocating for poverty reduction.

Methods

For this study, we applied critical interpretive synthesis (Dixon-Woods et al. 2006; Entwhistle et al. 2012), a research method used to generate a “synthesizing argument” from a diverse body of evidence. Critical interpretive synthesis has been widely applied in the health literature since coined by Dixon-Woods et al. (as of this writing, Google Scholar documents 417 citations). A distinguishing feature of this method is that it is useful for questioning the ways in which the literature constructs a topic and how the findings and assumptions from such an examination relate to action recommendations. In a critical interpretive synthesis, the examination of the literature is dynamic, meaning that it is done iteratively rather than linearly, recursive, meaning that the current analysis builds on previous analyses which can then be revisited and reshaped, and reflexive, meaning that relationships between ideas are consciously considered and then reconsidered to avoid flaws in logic or association produced during the process of synthesizing the literature. Rather than have a stage dedicated to applying specific inclusion and exclusion criteria to the literature that precedes data analysis, the sampling and selection process of material for review itself informs the synthesizing argument (Dixon-Woods et al. 2006, p. 6). This means that the collected literature needs to be continuously assessed and reassessed—and need not be exhaustive based on a priori search criteria. If the assembled literature for any given aspect of the topic is sufficient to draw inferences on, then the element is assigned the qualitative concept known as saturation (Miles and Huberman 1994). Similarly, another aspect of the topic may have insufficient literature to support inference but may be reported as an observation with the caveat that the finding is unsaturated.

Data collection

Our data source was the peer-reviewed academic literature on food banks between 1998, the date of publication of Sweet charity, and 2014. Consistent with critical interpretive synthesis, we employed a number of strategies to identify articles appearing in peer-reviewed journals that examined the food bank as a response to food insecurity. Articles that specifically described the implications of their findings in terms of action recommendations were given preference. In order to identify possible papers, we first searched databases (PubMed, Google Scholar, Scopus, SOCIndex, MEDLINE, CINAHL, ERIC, and Family and Society Studies Worldwide) using the keywords food bank, food pantry, food hamper, and food parcel. Then, manuscript reference lists were reviewed to identify relevant articles that may have been missed in the database search. We also sought suggestions from team members who were familiar with literature from affiliated fields.

Preliminary screening for inclusion was based on year published and content of title and abstract, with secondary screening based on content of introduction, discussion and conclusion of articles. Our inquiry was limited to countries with a similar political and economic structure to Canada, namely the US, Australia, New Zealand, and the countries of Western Europe. Articles could be written in English or French. Articles could describe and interrogate the food bank, its operations, and/or the nutritional quality of the food distributed at the food bank. Articles that discussed the emergency food system or food insecurity in general without direct reference to the food bank were excluded as were articles that focused on food bank users separate from their food bank experience. Articles that examined the rise in food bank use to alleviate food insecurity in the context of a dismantling of emergency food programs like the Food Stamp Program (now Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program [SNAP]) were included.Footnote 3

Included papers were original articles or reviews using either qualitative or quantitative methods. Commentaries were excluded unless they drew upon a synthesis of empirical data. Exclusions were not made on the basis of quality appraisal of study methodology, because the intent of the synthesis was to capture the contemporary food bank critique, not to appraise the quality of evidence overall in the field. Because the aim of critical interpretive synthesis is not to provide an exhaustive review of all data, we delineated the scope of the review using theoretical sampling (by time, countries, and use of various methodological approaches), and saturation requirements as described above (Dixon-Woods et al. 2006). In particular, we should note that the assembly of the vast literature on the quality of food distributed by food banks was curtailed when new articles did not enrich the analysis of this part of the critique. Notes regarding the article selection and exclusion process were recorded, and peer-debriefing assisted in the final selection decisions. In the end, 33 articles were selected for detailed examination (listed in Table 1).

Data analysis

Critical interpretive synthesis emphasizes the steps of research design, data sources, data collection, and ordering of data for analysis; beyond this, Dixon-Woods and colleagues (2006) are not directive about the precise qualitative analysis techniques to be used, but do provide generalized guidance on common qualitative research strategies that are foundational to qualitative research, including immersion, iterative coding, and crystallization for clarity (Borkan 1999; Bryman 2004). As we refined our findings, we also used peer debriefing (Miles and Huberman 1994).

Given our deliberate intent to examine whether the food bank critique has changed since Sweet charity, we used the original seven deadly “ins” as a foundational classification scheme against which articles were coded. As mentioned and defined above, Sweet charity identified seven “ins”: (1) inaccessibility, (2) inadequacy, (3) inappropriateness, (4) indignity, (5) inefficiency, (6) insufficiency, and (7) instability. These codes were applied to the articles using non-force fitting coding. When an article presented a concept that did not fit with the predetermined categories, we gave it a new code, trying to use the initial letters i-n, and considered how other concepts supported the new code or replaced it with one that gave the concept a more precise meaning. Through this method we identified five new “ins” to inform the food bank critique: (1) ineffectiveness, (2) inequality, (3) institutionalization, (4) invalidation of entitlements, and (5) invisibility.Footnote 4 , Footnote 5 Table 1 classifies each article according to applicable “ins.”

We also assigned each article to action recommendations (improve the food bank and/or eliminate or alleviate poverty) as a summative assessment of authors’ statements of what needed to be done, and/or next steps (Table 1). These were intended to be implicit recommendations from the direction of the suggestions made but often matched authors’ explicit recommendations suggesting technical improvements to food bank operations in the former case and strategies that might reduce poverty such as raising minimum wage rates in the latter case.

The emerging analysis also led to the revision and refinement of some of the codes derived from Sweet charity’s “ins.” For example, inappropriateness was expanded to encompass questions about whether some food donated to or distributed by food banks was unsafe to eat, and questions about insufficiency were expanded from strictly raising concerns about whether there was a failure to provide sufficient food to those accessing food banks to encompassing whether there was a failure to provide sufficient resources to these attendees to cope with food insecurity. Papers were manually coded with no limit on the number of codes a single paper could receive. Codes were assessed to be saturated or unsaturated in accordance with qualitative analytic approaches that assessed both the frequency of a code being applied to the articles, and the strength of the critiques that aligned with each code (Miles and Huberman 1994). Table 2 presents a description of the codes, the critique underlying each code, and examples from the literature.

After examining the final codes and the description of their accompanying critique, we worked with the analyses to derive synthetic constructs that would integrate the data. While there was some residual overlap for some codes, the resulting synthetic constructs, presented in Table 2, did not converge.

Findings

Altogether we reviewed 33 articles from Canada (16), the United States (10), Australia (3) and Europe (4). One Canadian author, Tarasuk, has published extensively for more than a decade on food banks (Tarasuk and Maclean 1990; Tarasuk et al. 2014a, b) and was represented in the data set by eight papers published since 1998 which were purposively selected for contributions to the broad food bank critique. Overlapping authorship in the dataset was otherwise rare (Daponte et al. 1998; Daponte and Bade 2006). Disciplinary backgrounds of authors were diverse, encompassing fields from political science to public health (Table 1).

Food bank critiques

Tables 1 and 2 outline in detail how the food bank critiques unfolded in our dataset. The contemporary food bank critique is most often concerned with questions related to indignity, instability, insufficiency, inadequacy, invisibility, and inappropriateness. Less often, it was described as raising questions about invalidation of entitlements, institutionalization, inefficiency, inequality, ineffectiveness, or inaccessibility. These less frequently considered “ins” were judged to be unsaturated and a sample of residual questions left unaddressed by each “in” is listed in Table 2. “Ins” were not necessarily independent of each other; for example, an examination of invalidation of entitlements was often linked to an examination of the invisibility critique, since invisibility was often assumed to be a precondition for invalidation of entitlements.

The food bank critiques were most often concerned with issues that arose from within the food bank. The only saturated critique beyond operations of the food bank was invisibility. As a whole, the dataset did not appear to contain a critique that was founded on the root causes of food insecurity leading to food bank use. This is not to say that academics did not recognize the connection between poverty, income inequality or other structural determinants of food bank use, but their critiques did not explicitly convey this association.

Action recommendations that arise from Food Bank critiques

Action recommendations based on the food bank critiques were split between the two a priori choices—improve the food bank, suggested by 17 papers, and eliminate or alleviate poverty, suggested by 14 papers. Only two authors invoked both action recommendations (Rock 2006; Tarasuk et al. 2014a). We found that the elimination and alleviation of poverty were two distinct concepts in the literature with authors tending to advance either the elimination or the alleviation of poverty, but not both simultaneously. However, these two approaches showed more similarity to each other than improve the food bank and were thus retained as a single category in our analysis.

Authors who described issues arising within the food bank tended to highlight operational aspects that were lacking and thus recommended actions to address such deficiencies. For example, inadequacy could be addressed with nutrition policies that stipulate the distribution of nutritious foods (Akobundu et al. 2004; Rambeloson et al. 2008); instability could be addressed with stable funding streams from government (Berner and O’Brien 2006); and the common critique insufficiency could be addressed with suggestions to increase donation volumes in an attempt to meet clients’ food needs (Booth and Whelan 2014; Tarasuk et al. 2014a). Of note, many of these authors also tended to be affiliated with nutrition- or public health-related disciplines.

In contrast, authors whose critique lay beyond food bank operations, were most often associated with social or political science disciplines, and noted that the food bank not only failed to respond to food security needs of users but also neglected to respond to the broader needs of those living in poverty. For example, the critique invalidation of entitlements could be addressed with suggestions to set a fair living wage that permits an individual to meet their basic needs (Riches 2002); and invisibility could be addressed by conducting research that examines food bank recipients’ actions and capabilities as they pertain to the acquisition of food in light of, or despite, food bank use (Lorenz 2012). An extension of this critique was that institutionalization could be addressed by lobbying policymakers to fight social welfare retrenchment (Lambie-Mumford 2013).

The critiques of ineffectiveness and inefficiency could be construed as comments on food bank operations but they also included questions about the performance of food banks relative to other programming options. Less often, authors’ food bank critique linked perceived failures in food distribution within the food system, and emergency food requirements (Wakefield et al. 2013).

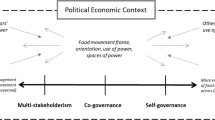

Our attempt to complete the final step of the critical interpretive synthesis methodology by deriving a synthetic construct integrating all results failed. We were left with two unlinked constructs underpinning the literature on food banks since Sweet charity. The first we call “operational challenges” and consolidates and affirms Sweet charity’s concerns with issues related to the day-to-day functioning of food banks that persist today. This synthetic construct incorporates the relative value of food banks in terms of the original “in” of inefficiency which wonders if food bank operations use resources well and the new “in” of ineffectiveness where there is a concern about whether food banks do a better job than other programs, for example the US SNAP program. The second synthetic construct we label “perpetuating inequity” as a way of capturing the academic literature’s concerns with the consequences of food banks persisting as a response today. The tension in this synthetic construct is that it suggests that food banks are to blame for this outcome, rather than inequities being an unintended consequence of food bank activity. When read and re-read, the underlying critiques of indignity, inequality, institutionalization, invalidation of entitlements, and invisibility, have a causal rather than incidental tone. Our findings are summarized in Fig. 1.

Discussion

We found that the contemporary food bank critique, when reviewed in light of Sweet charity, both consolidates the original list of “ins” and has expanded them over time. Newer “ins” specifically raise questions that go beyond looking at food bank operations. Each “in” raises questions about what food banks lack—and thus presents providing what is lacking as a tacit action recommendation. For example, the commonly cited question about whether food banks lack enough food for distribution (insufficiency) has sufficiency as a self-evident action recommendation. Depending on how insufficiency has been defined, sufficiency may mean increasing donation volume in an attempt to meet all clients’ caloric needs (Greger et al. 2002; Irwin et al. 2007) or adding additional services, such as employment counseling, to the food bank in an attempt to meet clients’ non-food needs (Butcher et al. 2014).

The five additional “ins” emerging from our analysis (invisibility, invalidation of entitlements, inequality, institutionalization, and ineffectiveness) suggest a growing academic literature that raises questions about whether the food bank is creating or perpetuating harm. For example, invalidation of entitlements questions whether validating charity as a response to hunger suggests that addressing hunger is optional, while simultaneously eroding public perception that an entitlement to be free from hunger—and thus a government responsibility to eliminate hunger—exists (Riches 2002; Thériault and Yadlowski 2000). The decreased governmental responsibility to address hunger leads to a reduced incentive to create, expand, or even maintain social welfare programs, leaving those vulnerable to hunger dependent on the food bank, with the attendant indignity, insufficiency, and other documented questions raised in the food bank critique.

It is worth noting that institutionalization was only questioned by six authors in the food bank critique. This may be because much of the critique of the risk of institutionalizing charitable food distribution pre-dates 1998. It is also plausible that food banks have become so entrenched and thus normalized as a legitimate component of the food system that their continued presence is often unquestioned—or that their elimination would be, at best, impractical, and at worst, unfathomable. Indeed, Handforth et al. (2013, p. 411) refer to food banks as “the foundation of the US emergency food system” and in fall 2013, a special issue of the Journal of Hunger and Environmental Nutrition, Special section: emergency food, was published. The focus of this issue was the interrogation of “food banks of the future” (Webb 2013), with a call for further formal collaboration between the emergency food system and health care, as well as corporate social responsibility programs: “Future partnerships are envisioned to link the food bank network more consistently with local nutritionists/registered dieticians, health care professionals, and community health clinics to address clients’ immediate food needs and to connect them to other health and nutrition services” (Webb 2013, p. 259).Footnote 6

The disciplinary background of authors appears to have a bearing on their approach to food bank critique. Although food insecurity is firmly rooted in poverty, the nutrition research community has taken ownership of the food bank critique as it pertains to research about the adequacy of food consumption, perceived nutritional vulnerability, and health outcomes of clients (Butcher et al. 2014; Jacobs Starkey and Kuhnlein 2000; Tarasuk et al. 2014b; Willows and Au 2006). Other health professionals have raised questions pertinent to both food banks and their practices leading to a critique that questions how food banks might operationally mitigate barriers (inaccessibility), reduce stigma (indignity), and increase cultural sensitivity (inappropriateness). Health professionals often recognize social structural factors as shaping, but not necessarily constitutive, of individual practices (Crawford 1980). Consequently, advocacy that supports social welfare reforms may be not be taken up and instead replaced with enhanced social inclusion goals of, in this case, food bank clients.

The tendency to focus on some research questions and not others within the food bank literature may also be related to authors’ perceptions regarding aspects of the food bank that could most realistically be studied and improved upon, an explanation that speaks to pragmatic imperatives within the academic enterprise. Similarly, the questions that authors address could be reflective of the interests of granting agencies to support projects likely to produce results that are easily measured and put into practice, i.e. within the realm of capacity of the intended targets. Procedural and operational improvements, nutrition policies, and improvements in access to food banks are more readily actionable than changing social welfare provisions that provide for basic needs, including food.

As a whole, the circulating food bank critiques within the contemporary academic literature since Sweet charity continue to raise questions about food bank operations, including concerns about the relative value of the food bank in relation to other programming options. Research questions on food bank operations focus on specific components of the food bank, e.g. whether the type of food provided is appropriate or whether this is sufficient human and capital resources to run an effective organization (Daponte and Bade 2006; Eisinger 2002; Tarasuk et al. 2014a). Fewer academics (nine papers) present a critique that suggests that the food bank response itself may be perpetuating inequity, through for example cultivating the impression that food insecurity is being adequately addressed. These critiques lend themselves to two synthetic constructs with very different sets of recommendations. The first addresses operational challenges and seeks ways to improve the food bank to reduce the perceived nutritional vulnerability of clients and meet other needs. The second appears directed at recommendations to eliminate or alleviate poverty but which originates from a literature that also implies that the food bank response itself needs to be exposed as one that perpetuates inequity. We would suggest that there is an inherent tension posed by these two synthetic constructs and that the recommendations that proponents would make on behalf of each could easily confuse policy makers if not provide contradictory advice.

Limitations

While attempts were made to find as many articles as possible, the aim was a theoretically systematic, but not exhaustive, literature review and therefore relevant articles may have been missed. It is also possible that other countries use different terminology for the food bank concept, which may have resulted in other relevant literature not being identified in our search. Another limitation is that we assumed that authors’ recommendations in their academic articles were produced for the purpose of policy advocacy as they have been encouraged to do when they address decision makers (Adily et al. 2009; Elliott and Popay 2000; Tetroe et al. 2008). We are also unable to ascertain how reviewer and editorial suggestions may have altered authors’ final recommendations.

The literature reviewed remains dominated by Canada and the United States represented by 26 of 33 papers. European countries have traditionally emphasized social welfare and redistributive policies that reduce poverty and economic inequities; hence their recent adoption of the food bank model is of particular concern as it renders invisible the social conditions that are leading to an increase in food insecurity. We do not think the food bank critique is well-articulated yet in these locales. For example, Loopstra et al.’s 2015 paper on the rise of food banks in the UK during a national election campaign addresses an entirely unique critique centered on: What economic conditions precipitate food bank introduction?

Conclusion

In this paper, we specifically asked: How does the contemporary food bank critique differ from Sweet charity’s seven deadly “ins”? We conducted a critical interpretive synthesis of the academic food bank literature published since Sweet charity in order to discern a synthetic construct that might support knowledge mobilization efforts for policy advocacy that would be applicable to the growing array of countries in which food banks operate today. We found that the list of original “ins” related primarily to food bank operations has been consolidated over time. We found additional “ins” that extend the food bank critique beyond operations to concerns about whether the food bank response itself perpetuates inequity. No construct emerged posing a challenge for mutually supportive policy advocacy.

Certainly, few academics would suggest improving food bank operations without at least the suggestion that the poverty that underpins food insecurity be addressed (Rock 2006); those who adopt structural questioning and raise equity concerns within the food bank critique would likely not suggest that those experiencing acute episodes of severe food insecurity be left to starve until society and its governments sort out the requirements for a fulsome social welfare and nutrition safety net (Tarasuk et al. 2014b). Nevertheless, contemporary scholarly inquiry suggests two disparate synthetic constructs related to food banks and we cannot help but conclude that advocacy efforts that link these constructs to different action recommendations will have a bearing on policy options produced as a result. Moreover, this knowledge synthesis raises practical questions for academics, particularly in multi-disciplinary fields with diverse influences, about whether and how we should deal with forces of convergence and divergence that emerge in an academic literature over time.

Notes

For an in-depth discussion, see the 2014 special issue of the British Food Journal 116(9).

Poppendieck’s (1998, Ch. 7) definitions for these terms were: inaccessibility (food is difficult to obtain because of poor location, hours of operation or transit options); inadequacy (food provided is not nutritious/lacks nutrients); inappropriateness (food provided does not meet dietary needs, or personal/cultural preferences of clients); indignity (using the food bank is a stigmatizing experience in which people may be treated with suspicion, depersonalized or lose some of their independence); inefficiency (emergency food is less efficient than the food stamp system and both systems are less efficient than the cash system, emergency food systems give the illusion of efficiency because they do not count donations as inputs); instability (emergency food supplies depend on donations of money, food, and labor that may be variable or unreliable); and insufficiency (the inability to provide sufficient food to meet clients’ needs).

These were exclusively articles from the US, which has a long history of distributing surplus commodities and food vouchers to people living in poverty. See Daponte and Bade (2006) for further information.

It should be noted that although these five “ins” were not identified in Sweet charity as part of the “seven deadly ‘ins,’” issues identified elsewhere in the book could be classified as describing many of the “ins” described here. We should also clarify that authors did not use the new “in-word” but it is rather the concept that they articulated that was so labelled.

Our definitions for these terms were: ineffectiveness (a critique that questions whether the food bank has met the goal of reducing food insecurity); inequality (creation or replication of unequal relationships in the food bank, usually between different classes); institutionalization (a process in which food banks become institutions and concerns for sustainability supersede service to clients); invalidation of entitlements (a process in which the establishment of the food bank as an acceptable response to hunger overrides the right to food); invisibility (the process by which the presence of food banks gives the impression that poverty is managed and thereby unseen).

This special publication was excluded from the synthesis because of its futurist perspective. Included articles examined the contemporary food bank problematic.

References

Adily, A., D. Black, I.D. Graham, and J.E. Ward. 2009. Research engagement and outcomes in public health and health services research in Australia. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 33: 258–261.

Akobundu, U.O., N.L. Cohen, M.J. Laus, M.J. Schulte, and M.N. Soussloff. 2004. Vitamins A and C, calcium, fruit, and dairy products are limited in food pantries. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 104: 811–813.

American Dietetic Association. 1990. Position of the American Dietetic Association: Domestic hunger and inadequate access to food. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 90: 1437.

Anderson, S.A. 1990. Core indicators of nutritional state for difficult-to-sample populations. Journal of Nutrition 120: 1559–1600.

Berner, M., and K. O’Brien. 2004. The shifting pattern of food security: Food stamp and food bank usage in North Carolina. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 33: 655–672.

Berry, J.M. 1984. Feeding hungry people. Rulemaking in the food stamp program. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press.

Booth, S., and J. Whelan. 2014. Hungry for change: The food banking industry in Australia. British Food Journal 116(9): 1392–1404.

Borkan, J.M. 1999. Immersion/crystallization. In Doing qualitative research, ed. B. Crabtree, and W.L. Miller, 179–194. London: Sage.

Bryman, A. 2004. Social research methods, 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Butcher, L.M., M.R. Chester, L.M. Aberle, V.J.-A. Bobongie, C. Davies, S.L. Godrich, R.A.K. Milligan, J. Tartaglia, L.M. Thorne, and A. Begley. 2014. Foodbank of Western Australia’s healthy food for all. British Food Journal 116(9): 1490–1505.

Campbell, C.C. 1991. Food insecurity: A nutritional outcome or a predictor variable? Journal of Nutrition 121: 405–412.

Campbell, C., S. Katamay, and C. Connolly. 1988. The role of nutrition professionals in the hunger debate. Journal of the Canadian Dietetic Association 49: 230–235.

Canadian Dietetic Association. 1991. The official position paper of the Canadian Dietetic Association on hunger and food security in Canada. Journal of the Canadian Dietetic Association 53: 139.

Crawford, R. 1980. Healthism and the medicalization of everyday life. International Journal of Health Services 10: 365–388.

Curtis, K.A. 1997. Urban poverty and the social consequences of privatized food assistance. Journal of Urban Affairs 19: 207–226.

Daponte, B.O., and S. Bade. 2006. How the private food assistance network evolved: interactions between public and private responses to hunger. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 35: 668–690.

Daponte, B.O., G.H. Lewis, S. Sanders, and L. Taylor. 1998. Food pantry use among low-income households in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania. Journal of Nutrition Education 30: 50–57.

De Schutter, O. 2012. End of mission statement: mission to Canada. Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. http://www.srfood.org/images/stories/pdf/officialreports/201205_canadaprelim_en.pdf. Accessed 14 March 2014.

Dixon-Woods, M., D. Cavers, S. Agarwal, E. Annandale, A. Arthur, J. Harvey, R. Hsu, S. Katbamna, R. Olsen, L. Smith, R. Riley, and A. Sutton. 2006. Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Medical Research Methodology 6(35): 1–13.

Eisinger, P. 2002. Organizational capacity and organizational effectiveness among street-level food assistance programs. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 31: 115–130.

Elliott, H., and J. Popay. 2000. How are policy makers using evidence? Models of research utilisation and local NHS policy making. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 54: 461–468.

Entwhistle, V., D. Firnigl, M. Ryan, J. Francis, and P. Kinghorn. 2012. Which experiences of health care delivery matter to service users and why? A critical interpretive synthesis and conceptual map. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy 17: 70–78.

Feeding America. 2014. Hunger in America 2014, national report. August 2014. http://www.feedingamerica.org/hunger-in-america/our-research/hunger-in-america/. Accessed 16 April 2015.

Food and Agriculture Organization. 1996. Rome declaration on world food security. http://www.fao.org/docrep/003/w3613e/w3613e00.htm. Accessed 5 April 2015.

Food Banks Canada. 2014. Hunger Count 2014. https://www.foodbankscanada.ca/getmedia/7739cdff-72d5-4cee-85e9-54d456669564/HungerCount_2014_EN.pdf.aspx?ext=.pdf. Accessed 23 October 2015.

Frederick, J., and C. Goddard. 2008. Sweet and sour charity: experiences of receiving emergency relief in Australia. Australian Social Work 61: 269–284.

Greger, J.L., A. Maly, N. Jensen, J. Kuhn, K. Monson, and A. Stocks. 2002. Food pantries can provide nutritionally adequate food packets but need help to become effective referral units for public assistance programs. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 102(8): 1126–1128.

Handforth, B., M. Hennick, and M.B. Schwartz. 2013. A qualitative study of nutrition-based feeding initiatives at selected food banks in the Feeding America network. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 113: 411–415.

Husbands, W. 1999. Food banks as antihunger organizations. In For hunger-proof cities: Sustainable urban food systems, ed. M. Koc, and R. MacRae, 103–109. Ontario: IDRC Books.

Irwin, J.D., V.K. Ng, T.J. Rush, C. Nguyen, and M. He. 2007. Can food banks sustain nutrient requirements? A case study in southwestern Ontario. Canadian Journal of Public Health 98: 17–20.

Jacobs Starkey, L., and H.V. Kuhnlein. 2000. Montreal food bank users’ intakes compared with recommendations of Canada’s food guide to healthy eating. Canadian Journal of Dietetic Research and Practice 61: 73–75.

Kennedy, A., J. Sheeshka, and L. Smedmor. 1992. Enhancing food security: a demonstration support program for emergency food center providers. Journal of the Canadian Dietetic Association 53: 284–287.

Kirkpatrick, S.I., and V. Tarasuk. 2009. Food insecurity and participation in community food programs among low-income Toronto families. Canadian Journal of Public Health 100: 135–139.

Lambie-Mumford, H. 2013. “Every town should have one”: Emergency food banking in the UK. Journal of Social Policy 42: 73–89.

Lipsky, M., and M.A. Thibodeau. 1988. Feeding the hungry with surplus commodities. Political Science Quarterly 103: 223–244.

Loopstra, R., A. Reeves, D. Taylor-Robinson, M. McKee, and D. Stuckler. 2015. Austerity, sanctions, and the rise of food banks in the UK. British Medical Journal 350: h1775. doi:10.1136/bmj.h1775.

Lorenz, S. 2012. Socio-ecological consequences of charitable food assistance in the affluent society: the German Tafel. International Journal of Sociology and Social policy 32: 386–400.

Miles, M.B., and A.M. Huberman. 1994. Qualitative data analysis. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Nord, M., M.D. Hooper, and H.A. Hopwood. 2008. Household-level income-related food insecurity is less prevalent in Canada than in the United States. Journal of Hunger and Environmental Nutrition 3(1): 17–35.

Paynter, S., M. Berner, and E. Anderson. 2011. When even the “dollar value meal” costs too much: food insecurity and long-term dependence on food pantry assistance. Public Administration Quarterly 35: 26–58.

Poppendieck, J. 1998. Sweet charity? Emergency food and the end of entitlement. New York: Viking.

Poppendieck, J. 2000. Hunger in the United States: Policy implications. Nutrition 16: 651–653.

Rambeloson, Z.J., N. Darmon, and E.L. Ferguson. 2008. Linear programming can help identify practical solutions to improve the nutritional quality of food aid. Public Health Nutrition 11: 395–404.

Riches, G. 1986. Food Banks and the welfare crisis. Ottawa, Ontario: Canadian Council on Social Development.

Riches, G. 1996. Hunger in Canada: Abandoning the right to food. In First World hunger: Food security and welfare politics, ed. G. Riches, 46–77. London: Broadview Press.

Riches, G. 1997. Hunger, food security, and welfare policies: Issues and debates in First World societies. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 56: 63–74.

Riches, G. 2002. Food banks and food security: Welfare reform, human rights, and social policy. Lessons from Canada? Social Policy & Administration 36: 648–663.

Riches, G. 2011. Thinking and acting outside the charitable food box: Hunger and the right to food in rich societies. Development in Practice 21(4–5): 768–775.

Rock, M. 2006. “We don’t want to manage poverty”: Community groups politicize food insecurity and charitable food donations. IUHPE: Promotion & Education 13: 36–41.

Starkey, L.J., and K. Lindhorst. 1996. Emergency food bags offer more than food. Journal of Nutrition Education 28: 183.

Tarasuk, V. 2001. A critical examination of community-based responses to household food insecurity in Canada. Health Education and Behavior 28: 487–499.

Tarasuk, V.S., and G.H. Beaton. 1999. Household food insecurity and hunger among families using food banks. Canadian Journal of Public Health 90: 109–113.

Tarasuk, V., and B. Davis. 1996. Responses to food insecurity in the changing Canadian welfare state. Journal of Nutrition Education 28: 71–75.

Tarasuk, V., and J.M. Eakin. 2003. Charitable food assistance as symbolic gesture: an ethnographic study of food banks in Ontario. Social Science and Medicine 56: 1505–1515.

Tarasuk, V., and J.M. Eakin. 2005. Food assistance through “surplus” food: insights from an ethnographic study of food bank work. Agriculture and Human Values 22: 177–186.

Tarasuk, V.S., and H. MacLean. 1990. The institutionalization of food banks in Canada: A public health concern. Canadian Journal of Public Health 81: 331–332.

Tarasuk, V., N. Dachner, A.-M. Hamelin, A. Ostry, P. Williams, E. Bosckei, B. Poland, and K. Raine. 2014a. A survey of food bank operations in five Canadian cities. BMC Public Health 14: 1234. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-14-1234.

Tarasuk, V., N. Dachner, and R. Loopstra. 2014b. Food banks, welfare, and food insecurity in Canada. British Food Journal 116(9): 1405–1417.

Teron, A.C., and V.S. Tarasuk. 1999. Charitable food assistance: What are food bank users receiving? Canadian Journal of Public Health 90: 382–384.

Tetroe, J.M., I.D. Graham, R. Foy, N. Robinson, M.P. Eccles, M. Wensing, P. Durieux, F. Légaré, C.P. Nielson, A. Adily, J.E. Ward, C. Porter, B. Shea, and J.M. Grimshaw. 2008. Health research funding agencies’ support and promotion of knowledge translation: An international study. Milbank Quarterly 86: 125–155.

Thériault, L., and L. Yadlowski. 2000. Revisiting the food bank issues in Canada. Canadian Social Work Review 17: 205–233.

Tsang, S., A.M. Holt, and E. Azevedo. 2011. An assessment of the barriers to accessing food among food-insecure people in Cobourg, Ontario. Chronic Diseases and Injuries in Canada 31: 121–128.

van der Horst, H., S. Pascucci, and W. Bol. 2014. The “dark side” of food banks? Exploring emotional responses of food bank receivers in the Netherlands. British Food Journal 116(9): 1506–1520.

Wakefield, S., J. Fleming, C. Klassen, and A. Skinner. 2013. Sweet charity, revisited: Organizational responses to food insecurity in Hamilton and Toronto, Canada. Critical Social Policy 33: 427–450.

Warshawsky, D.N. 2010. New power relations served here: The growth of food banking in Chicago. Geoforum 41: 763–775.

Webb, K.L. 2013. Introduction—Food banks of the future: Organizations dedicated to improving food security and protecting the health of the people they serve. Journal of Hunger and Environmental Nutrition 8: 257–260.

Willows, N.D., and V. Au. 2006. Nutritional quality and price of university food bank hampers. Canadian Journal of Dietetic Research and Practice 67: 104–107.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this project was provided through the CIHR Operating Grant: Programmatic Grants to Tackle Health and Health Equity, ROH—115208.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McIntyre, L., Tougas, D., Rondeau, K. et al. “In”-sights about food banks from a critical interpretive synthesis of the academic literature. Agric Hum Values 33, 843–859 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-015-9674-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-015-9674-z