Abstract

The food sovereignty movement calls for a reversal of the neoliberal globalization of food, toward an alternative development model that supports peasant production for local consumption. The movement holds an ambiguous stance on peasant production for export markets, and clearly prioritizes localized trade. Food sovereignty discourse often simplifies and romanticizes the peasantry—overlooking agrarian class categories and ignoring the interests of export-oriented peasants. Drawing on 8 months of participant observation in the Andean countryside and 85 interviews with indigenous peasant farmers, this paper finds that export markets are viewed as more fair than local markets. The indigenous peasants in this study prefer export trade because it offers a more stable and viable livelihood. Feeding the national population through local market intermediaries, by contrast, is perceived as unfair because of oversupply and low, fluctuating prices. This perspective, from the ground, offers important insight to movement actors and scholars who risk oversimplifying peasant values, interests, and actions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

As an alternative to global industrial agriculture, food sovereignty positions “the peasant way” as the basis for a sustainable and socially just food system. Coined by the international peasant movement, Via Campesina,Footnote 1 food sovereignty calls for a turn away from neoliberal policies which advantage corporate interests. The original definition of food sovereignty put forth in 1996 focused on the rights of nations to develop their capacities to produce their own food. Although the focus has shifted over time, the model is largely oriented toward government-supported, small-scale, agro-ecological production for local consumption. A Via Campesina leaflet from 2007 states:

Food sovereignty organizes food production and consumption according to the needs of local communities, giving priority to production for local consumption. Food sovereignty includes the right to protect and regulate national agricultural and livestock production and to shield the domestic market from the dumping of agricultural surpluses and low-price imports from other countries.

The sixth international conference agenda makes clear “We will continue to promote and defend peasant-based, agro-ecological production as a real answer to the climate crisis” (Via Campesina 2014, p. 32). Despite shifting emphasis from national food self-sufficiency to global climate change, food sovereignty solidly places peasant production for local consumption at the heart of its agenda.

This paper uncovers the assumed linkage between peasant farmers and local consumers. National governments and international institutions have shown increased receptivity to the food sovereignty platform. Yet, peasant farmers themselves are not necessarily in favor of local food and opposed to long-distance international trade. In fact, the peasant farmers in this study prefer export markets.

Ongoing debate about the benefits of and inequalities inherent to global agricultural trade has continued since colonial independence in nineteenth century Latin America (Frank 1978; Cardoso and Faletto 1979; McMichael 2009; Jarosz 2011). Currently, a discursive shift back to national sovereignty is gaining strength. Oliver de Schutter, the United Nations General Assembly Special Rapporteur on the right to food, submitted a report to the UN Human Rights Council titled “The Transformative Potential of the Right to Food” (De Schutter 2014). This report shares criticisms of the global food system and suggests policy changes that are in line with food sovereignty objectives. For example, he reports: “The food systems we have inherited from the twentieth century have failed. Of course, significant progress has been achieved in boosting agricultural production over the past 50 years. But this has hardly reduced the number of hungry people” (4). Most of his initiatives are oriented toward strengthening the ability of countries to increase their own production to meet a greater share of their own food needs—and doing so through support to small-scale farmers.

In October 2013, Via Campesina and UN FAO director general Jose Granziano da Silva formalized an agreement of cooperation which acknowledges the role of smallholder food producers in the eradication of world hunger (Via Campesina 2014, p. 5). They also have a joint partnership with United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) to advance agro-ecology and peasant farming as alternatives to industrial farming. A UNCTAD (2013) report titled “Wake up before it is too late: make agriculture truly sustainable now for food security in a changing climate” states that farming should shift from monoculture toward greater variety of crops, reduced use of fertilizers and other inputs, greater support for small-scale farmers, and more locally focused production and consumption of food.

This discourse has even been adopted in the national constitutions of Venezuela, Ecuador, Bolivia, Mali, Nepal and Senegal. The 2008 Constitution of Ecuador asserts soberanía alimentaria as a strategic goal and governmental obligation to ensure that people, communities, pueblos and nationalities reach self-sufficiency of healthy and culturally appropriate food (Republic of Ecuador 2008, Article 281). It states that “Individuals and communities have the right to safe and permanent access to healthy, sufficient and nutritious food, in accordance with their different identities and cultural traditions, preferably locally produced” (Article 13). Food sovereignty was included in the 2008 constitution largely through the involvement of indigenous movement actors in the constitutional reform process (Becker 2013; Giunta 2013; Clark 2015). In the years leading up to the election of Rafael Correa and his revolución ciudadana (citizens’ revolution) to write a new constitution, the Ecuadorian indigenous peasant movement marched against neoliberal agriculture and trade policies. Escobar (1995) highlights the significance of the Sumak Kawsay cosmology of indigenous and peasant groups in Ecuador as an alternative indigenous development paradigm in opposition to modernization and neoliberalism; Edelman (2005) boasts how the Via Campesina member organizations in Ecuador toppled neoliberal governments on several occasions.

Indigenous peasants in the Ecuadorian Andes were selected as the research subjects for this case study because of their rich recent history with food sovereignty activism. They constitute the base of both national and international peasant movement organizing. Via Campesina routinely emphasizes the importance of peasant voice in the formation of food policies. Against this backdrop, we should pay greater attention to the explicit preferences and perspectives of peasants.

This article analyzes the discourse of a sample of indigenous peasant farmers in Ecuador regarding their experiences selling crops in both national and international markets. The sample is made up of “middle peasant” farmers who derive their livelihood from farm income, as opposed to semi-proletariat peasants who farm only for household consumption. To gather a variety of outlooks, I selected three groups of indigenous peasant farmers, each of which specializes in a different commodity: quinoa, broccoli, and milk. I found that these indigenous peasant farmers did not prioritize agricultural production for local consumption and national self-sufficiency. Based on their experiences supplying export commodity chains and selling crops in the domestic market through local market intermediaries, they prefer export markets for their comparatively stable prices.

This finding should not be surprising given the historically cheap and undervalued price of national staples in Latin America. De Janvry (1981) reveals the structural inequality that characterizes domestic food supply under a system of functional dualism. This finding is surprising, however, in light of food sovereignty discourse that presents peasant agriculture as distinct from capitalist globalization. To romanticize local consumption obscures the history of unequal urban–rural relations. Food sovereignty scholars and activists should attend more closely to peasant trajectories of agrarian modernization, and acknowledge the diverse livelihood interests of contemporary peasant farmers, rather than implying a homogenous group of capitalism’s ‘Other’ (Bernstein 2014). The overwhelming preference for export markets among peasant farmers in this study makes it likely that a large and growing sector of peasant farmers in the Global South hold interests that are not explicitly addressed (and in some cases, even opposed) by the international peasant movement that represents them.

Food sovereignty and international trade

The food sovereignty movement (FSM) has received growing scholarly attention. Within 6 months, two conferences were held on the topic: one at Yale University in September 2013 and the other at The Hague, Netherlands in January 2014. Edelman et al. (2014) point out that food sovereignty is a dynamic process rather than fixed principles set in stone. Although the focus of the movement has shifted over time, agro-ecology and international trade are two central concerns.Footnote 2 Early literature situated food sovereignty as the pillar of transnational peasant movement Via Campesina (Desmarais 2008); more recent scholarship traces the early roots of the concept and breadth of the political agenda beyond Via Campesina (Edelman et al. 2014).

Scholars of the FSM cast it as an alternative political economy of food, pointing to the important role of peasant farmers in the production of food (Van der Ploeg 2014; McMichael 2014). It is estimated that they produce over half—and as much as 70 %—of the world’s food supply (McMichael 2014, p. 951). This literature backs the activists’ rallying cry that peasants “feed the world and cool the planet” through their sustainable methods and localized trade (McMichael 2011). The food security model of comparative advantage, in this view, focuses on increasing the quantity of food through modern technologies at the expense of ecological concerns over where or how it is produced. Yet still, many poor people around the globe are denied access to sufficient food because of the way it is distributed. Therefore, it is argued, small farmers can both feed the world and cool the planet. The food they produce is more likely to reach local hungry populations in poor countries. And in doing so, will reduce the global greenhouse emissions associated with green revolution technologies and long distance trade (Van der Ploeg 2014; GRAIN 2013). The ecological perspective on international trade complements critiques rooted in colonial history: “the reconfiguration of land and social relations to produce commodities for export obviously has old roots in European colonialism” (Edelman et al. 2014, p. 915). For these reasons, the FSM “has tended to view long-distance or foreign trade of agricultural products in a negative light” (p. 915).

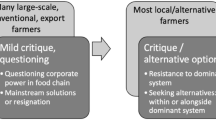

Over time, the FSM has become more open to international trade under certain circumstances. Yet their position on the issue is “ambiguous, unclear and sometimes contradictory” (Burnett and Murphy 2014, p. 6). The original definition of food sovereignty put forth by Via Campesina in 1996 focused on the rights of nations to develop their capacities to produce their own food. It is often described as a way to help food deficit countries move toward greater food self-sufficiency (Edelman et al. 2014). Because of its origin and strict rejection of the WTO, the movement leaves the impression that it remains opposed to international trade. Edelman et al. (2014, p. 916) refer to trade and distance as a “sticky issue for food sovereignty.” Even if their stance has evolved to accept trade under certain circumstances, the FSM clearly prioritizes local market exchange over global trade, assert Burnett and Murphy (2014).

Due to this and vague and ambiguous approach to international trade, a few scholars have begun to question the FSM’s representation of peasants. “What do we make of the millions of smallholders who produce agricultural commodities for export?” ask Edelman et al. (2014, p. 915). Is it possible to incorporate them into a food sovereignty model? Burnett and Murphy (2014) agree. The neglect of international trade, they argue, risks marginalizing the tens of millions of smallholder producers and farm workers who earn their living from growing crops for export. Peasants whose livelihoods are dependent on export markets do not necessarily want to exit international markets; they want to integrate more equitably into the global system. They are looking for practical opportunities instead of radical and ideological change. Above all, producers want to improve their economic bargaining power in the markets they already know.

Whether producing for fair trade markets, or traditional or non-traditional agricultural commodity chains, some fieldwork evidence suggests these producers are motivated to continue their engagement in export markets. Millions of farmworkers, too, want to improve their working conditions, but are also protective of their jobs. They perceive international trade to be important for their livelihoods (Burnett and Murphy 2014, p. 16).

Other scholars have found similar trends among small farmers engaged in export markets (Fischer and Benson 2006; Finan 2007; Walsh-Dilley 2013). Studies of peasant development discourse on export agriculture find that vegetable farmers in Guatemala and Peru hold up exporting as an ideal. They are thankful of the improvements they are able to provide their families with as a result of the higher prices they receive through exporting vegetables like broccoli and snap peas. Walsh-Dilley’s (2013) case study of quinoa farmers in Bolivia provides further empirical support for Burnett and Murphy’s claim that small farmers want to continue exporting. Although traditional forms of production persist (reciprocal labor exchange; preparing the soil by hand instead of with tractors), these traditional practices are utilized strategically in order to improve their returns in the quinoa export market. “This takes place not alongside struggles to resist capitalist processes, but rather precisely as San Juaneños are seeking to become even more closely aligned with markets and market opportunities,” explains Walsh-Dilley (2013, p. 675). And lastly, a number of scholars point to the benefits of fair trade certified export markets compared to selling to local intermediaries (Bacon 2005; Jaffee 2007).Footnote 3

This literature, however, remains largely ignored by food sovereignty scholars. Burnett and Murphy (2014, p. 22) call for empirical research that examines the question of market interests from the perspective of producers themselves: “Dialogue with small-scale producers whose crops are sold in export markets will be an important part of this, to understand their interests and their motivations, and to use this understanding to broaden the scope of food sovereignty.” This is precisely what my research accomplishes. From my sample of indigenous peasant farmers, I found that they prefer to sell their crops in export markets and want to continue exporting more products—largely because of the problems they face in the local market. The following section helps explain this finding by providing context on peasant class categories and the structural disadvantage of supplying food to the national market.

Peasants, capitalism and the national market

Literature on FSM is prone to oversimplify and romanticize peasants (Rossett 2000; Borras et al. 2008; Lawrence and McMichael 2012). Recently, certain scholars have begun to critique the way food sovereignty activists and scholars oversimplify peasants as inherently anti-capitalist (Fitting 2011; Bernstein 2014). Fitting (2011) problematizes the discourse utilized in the anti-GMO corn campaign in Mexico. She warns of the cultural essentialism that can take place in portrayals peasant agriculture: “Peasant communities have been romanticized as being predisposed to simple reproduction, averse to profit, or constituted by egalitarian relations” (p. 22). When Via Campesina activists claim that Mexican indigenous peasant producers have always existed in harmony with nature, they misrepresent those groups as part of a millennial culture, distinct from the capitalist economy of modern Mexico. “In Defense of Maize can slip into peasant essentialism and a bounded, reified conception of culture” (p. 114), Fitting argues.

Distinguished agrarian scholar Bernstein (2014) critiques FSM discourse for giving an abstract and unitary conception of peasants. He problematizes the false binary between capitalist industrial and peasant agriculture under the “overarching framework of the vicious and virtuous” (p. 1031). In contemporary discourse, peasants have become capitalism’s ‘Other’:

They qualify as capital’s other by virtue of an ensemble of qualities attributed to them, which include their sustainable farming principles and practices, their capacity for collective stewardship of the environments they inhabit…and their vision of autonomy, diversity and cooperation (p. 1041).

Bernstein (2014, p. 1057) is skeptical of the way that the FSM “discards crucial elements of agrarian political economy” in order to establish its binary. He situates this view of peasants as noble, moral and ecologically superior as the “trope of agrarian populism”. It did not begin with the FSM, but it is perpetuated by them. Movement rhetoric collapses together the term “peasant” that in fact represents several different agrarian class categories with different interests.

In agrarian scholarship, the definition of “peasant” varies, but one consistent factor holds true throughout: family as the unit of production. Peasants are defined not by the products they produce, or their market destination, but by the social basis of production. Peasants use family members as the primary source of labor; that characteristic is what distinguishes peasant farmers from capitalist farmers. Bryceson (2000) defines peasants based on the criteria that they (1) live in a community settlement, (2) are subordinate to the dominant class; (3) use family labor; and (4) combine subsistence and commodity production. In the introduction to the edited volume Peasants and Globalization, Akram-Lodhi and Kay (2009, p. 3) define peasants as “an agricultural worker whose livelihood is based primarily on having access to land… and who uses principally their own labor and the labor of other family members to work that land.” “Peasants do not live in isolation from wider social and economic forces,” Akram-Lodhi and Kay add, “the subordinate position of peasants affects the complex network of social relationships they enter into with others, [and] the economic transactions they undertake with others” (p. 3). It is understood that peasants maintain a subordinate position in society. Yet their subordinate position still allows for considerable heterogeneity. Two sub-classes of peasants are widely recognized: semi-proletariat and petty commodity producers.

In his classic work, The Agrarian Question and Reformism in Latin America, De Janvry (1981) distinguishes between “lower peasants” and “middle peasants.” Lower peasants are a semi-proletariat class of subsistence farmers and wage earners, while middle peasants are petty commodity producers. Middle peasants are subject to domination by more powerful actors, and characterized by hyper-exploitation of family labor. As such, it is a highly unstable class category that is expected to quickly differentiate into capitalist farmers and semi-proletarian peasants.

De Janvry (1981) did not predict a lasting middle peasantry. However, it clear there remains an agrarian class of petty commodity producers who do not farm for subsistence alone, but rather derive their living from agricultural sales. These peasants are the subject of this study. Distinguishing between middle and semi-proletariat peasants helps clarify the seeming contradiction between peasant livelihoods and the FSM’s stance on international trade. For those peasants whose livelihoods depend on their agricultural commodities, the national market may not be the most appealing option.

Structurally, the relationship between rural food producers and urban food consumers is unbalanced in favor of the urban at the expense of the rural. De Janvry (1981) uses the term ‘functional dualism’ to characterize the national food market after the end of the hacienda system. Functional dualism provided cheap food for the growing urban population through the cheap labor of rural semi-proletarians. The cost of reproduction for urban wage labor is tied to the cost of food. Therefore, lowering food prices in the national market is integral to industrialization. During the mid twentieth century, there was systematic downward political pressure on the price of food staples.

In agrarian political economy, peasants are defined by their family unit of production, not by which crops they grow or the market destination of those crops. Thus, export-oriented peasants are still peasants. Despite movement rhetoric, not all peasants reject globalization in defense of national self-sufficiency. The systematic downward pressure on national market prices, along with peasants’ desires to maintain and improve their rural livelihoods, explain their preference to export.

Methods

Data for this paper comes from 8 months of ethnographic field research in the Ecuadorian countryside. I conducted research in three different communities, which were selected for comparison because they are similar in many indicators—ethnicity, class, land size holdings, age and gender composition—yet differ in the cash crops they grow and commodity chains they supply.

The small farmers in this study all come from the same historically marginalized ethno-class of indigenous peasants. Each of the three communities in this study self-identifies and is legally registered as indigenous. They share similar histories of agrarian reform access to collective land titles (Korovkin 1997). Each community has subdivided communal land into individual family household plots. They hold similar cultural norms, such as traditional gendered division of labor, and a particular style of dress that differs from urban mestizo Ecuadorians and even fellow rural, yet mestizo, peasants.

While some members of these communities have migrated to urban areas, the community members who participated in this study remain stationed in the rural countryside with agrarian-based livelihoods. They sustain their livelihoods through subsistence and commercial agriculture, and sell part of their commercial production to export intermediaries. The farmers in this study supply both local and export markets, yet the markets they supply are vastly different. Such heterogeneous commercialization makes it all the more interesting and noteworthy that they have similar perceptions of local and export markets.

In each of the three communities, campesinos specialize in the same commercial crops as their fellow community members. In Quiloa,Footnote 4 farmers specialize in grains: quinoa, barley, and wheat. In Brocano, farmers specialize in vegetables (hortalizas): broccoli, cauliflower, lettuce, carrots, onions, beets and cilantro. In Lacava, community members specialize in dairy farming. Alongside commercial production, most of the campesinos in Quiloa, some in Lacava, and few in Brocano grow family gardens of staple food crops for self-consumption in addition to eating part of the output of the commercial crops they grow.

The three communities represent variety among export-integrated campesinos. They grow very different crops and supply different commodity chains: (1) broccoli seeds are imported, chemical-intensive, water-intensive, labor-intensive, and harvested every 3 months; (2) quinoa is a native grain, organic, labor-intensive, and harvested once a year; (3) milk is collected twice a day, requires more land and water, yet minimal labor. Each of the farming communities are integrated into different types of markets. Quiloa farmers sell quinoa, barley, and wheat to local market intermediaries at the weekly plaza and export certified organic quinoa through several non-profit development NGOs. Quinoa is then shipped to the US and several European countries. Brocano farmers sell their vegetables to merchants who truck the produce directly to the wholesale market in Guayaquil, the largest city in Ecuador, 5 h away. Brocano farmers also export their broccoli through a national agribusiness firm which processes frozen broccoli to export to the US, Turkey, and Japan alongside other non-traditional export agriculture crops, like mangoes. Dairy farmers in Lacava sell their milk to a small agribusiness firm that processes condensed milk for sale in national supermarkets and export to Venezuela.

Participant observation and informal interviews at the markets provides evidence on the destination of the crops sold to local intermediaries. Broccoli is trucked to the mercado mayorista (wholesale market) in the country’s largest city, Guayaquil, where the intermediaries sell the produce in stalls to other vendors who buy a variety of products to sell at mercado minoristas, smaller markets around the city. Since intermediaries buy 20 or 30 sacks of broccoli at a time, and re-sell one at a time to each vendor, it is likely that the final destination is urban consumption within the country, not export. Milk from the Lacava’s centro de acopio is sold to a few small factories in the nearby city to make yogurt and cheese. The majority of their milk, however, is sold directly to a national company located 70 miles south in Machachi, the agro-export zone just south of the capital city, Quito. From the processing plant, milk products are sold in national supermarket chains and exported to Venezuela. As for Quiloa, local intermediaries purchase quinoa from the small farmers in quantities ranging from a dozen 100-pound sacks (quintales) down to 20 pounds. They then turn around and re-sell all their quintales to different intermediaries with cargo trucks. These intermediaries take the quinoa from the mercado minorista to the mercado mayorista where they supply grain vendors with quinoa in their bodegas (grain stores) to sell directly to consumers by the pound. They also sell to supermarkets who package the quinoa under their own brand name. It is possible that the intermediaries sell some of the quinoa to exporters or smuggle it across the northern border; however, for the most part, quinoa sold to local intermediaries is consumed in the country by urban dwellers who shop at supermarkets and bodegas.

To understand the experiences of indigenous campesino farmers with export agriculture, I resided in each community for a minimum of 1 month, living with families in their homes and participating in their daily activities. In addition to interacting with community members informally on a daily basis, I conducted formal interviews with 85 campesinos total: 21 residents of Brocano, 26 residents of Lacava and 38 residents of Quiloa. The ages of respondents ranged from 20 to 70; the most common respondents were 40-year-old women. This is partly due to my sampling strategy. To recruit people to be in my study, I walked through the community, greeting people as we passed each other on the road, and introducing myself as a researcher. Middle-aged women were most likely to be in these locations and have time to talk. Many of these interviews took place alongside daily chores, such as washing clothes, feeding chickens, or peeling potatoes. These conversations also took place in the fields while harvesting quinoa, fumigating broccoli, milking cows, weeding vegetable gardens, or shoveling manure.

Each community has a similar gendered division of labor: women are responsible for most household chores while men are more likely to earn income from outside of the community through wage labor in nearby cities. Nevertheless, I was still able to interview a good number of men, young and old. Thirty-two interviewees were men, making up 34 % of respondents in Quiloa, 38 % in Brocano and 42 % in Lacava. In addition to interviews and participant observation inside the communities, I accompanied farmers to markets when they went to sell their products. This task is done by both men and women heads of household. Although women are primarily responsible for domestic labor in the home, they also participate in male-dominated activities such as inheriting land, planting commercial crops, and selling goods at the market. I also spent hours on my own each week observing market interactions between farmers and intermediaries.

To analyze my data, I thematically coded what interview respondents said about food production, consumption, trade, protests, and how they felt their experiences with agriculture could be improved. What stood out to me was the continuity between their responses about whether it is better to sell their crops to consumers in Ecuador or export to other countries. Going into this project, I expected to find more heterogeneous responses within and between communities. As it turns out, I did find substantial difference with regard to food production, consumption, and protest practices. However, I found surprisingly little difference on the topic of market trade. Farmers discuss similar experiences with export and local markets.

Findings

The indigenous peasant farmers in this study are strongly in favor of participating in international trade. During my interviews, I asked every farmer the same question: “Is it better to sell your crop in this country, or export to other countries?” The overwhelming response was “it is better to export.” Out of 85 interviews, all but one responded in this way. The one person who initially responded that it is better to sell in the domestic market—a middle-aged female quinoa farmer in Quiloa—qualified her response with “if it was more fair.” This association of export markets with “fair” and domestic markets with “unfair” is common across interviews. Explanations for why export markets are preferred center around the high and fixed price offered by export markets and the low, unstable, and unfair price received in the domestic market by selling to local intermediaries.

This collective response in favor of international trade is interesting given the differences between the commodity chains that these three groups of indigenous peasant farmers supply. One would expect the fair trade farmers to prefer export trade (because of the long-term contracts and guaranteed price), but not necessarily the conventional vegetable and dairy farmers. However, regardless of the commodity—and its distinct production and market characteristics—in all three cases, the local market mechanisms are perceived to be so poor that export chains are the preferred alternative.

From the interview responses below, it is clear to see that solidifying a stable livelihood is foremost important to these indigenous peasant farmers. Neither feeding fellow Ecuadorians or reducing the distance food is transported is of concern to them. The following findings section begins with explanations for market preference that is common among farmers, then differentiates the specific circumstances of each community and its commodity, and ends with a discussion of what constitutes a fair market in their eyes.

Price

Farmers in all communities shared their stories and complaints about the prices they receive for their products when they sell in the domestic market. They reveal the hardships faced by selling their current cash crop, as well as other crops they currently or previously have sold, in the local market. By comparison, they claimed that selling their crops in the export market brings in a stable, constant, predictable price.

Broccoli farmer Alma tells me, “We campesinos are on the land, with the crops, day and night. For us, it is better, more profitable, to export. It is better that there is a lot of movement and trade. It is better not to be stuck only in the national market, but rather the international market.” Indigenous peasant farmers see themselves as deserving of this chance to make extra money because the work they do in the fields is strenuous. It requires a lot of labor to prepare these products, yet they hold little value in the Ecuadorian market. With regard to exporting quinoa, Liana from Quiloa says “It is a good thing how we are producing a few cents more for ourselves here, to benefit ourselves. For us, to work, to grow quinoa, it’s tough, the work is tough.”

The comparison between the price of their products in export markets compared to internal markets came up again and again. Leonardo from Brocano says “it is better that products from here, Ecuador, go abroad and profit a little more. Here it is cheaper. There, when you sell abroad, it is more expensive.” Belén from Lacava shares this same sentiment: “It is better to export because here it’s always cheap.” Gladys from Lacava says it is good to export milk “because they pay us a little more.” If there was not enough milk to meet the demands of Ecuadorians, then would it be better to sell milk only in this country? I asked. “No, I see the better option as always to export.”

Low local market price is attributed to overproduction and too much competition. Gerónimo is a 60-year-old man from Lacava who works on a flower plantation while his wife takes care of their vegetable garden and milks the cows. Even though he has worked 20 years at the same plantation, he makes minimum wage, and most of their family income comes from the sale of milk from their four cows. He says “It is better to sell to other countries because they pay more. Because here they don’t pay the same price, it is very cheap. Because here there is so much.”

Esteban from Brocano also points to overproduction and competition between farmers: “I think that since there is a lot of competition here in Ecuador, it would be better to sell to other countries if there is a market, so the future generations can advance little by little. It’s best these days to look for other markets to sell to other countries.” Quinoa farmer Ana points to the fact that everybody grows the same things as each other, saturating the local market at harvest time. “Sometimes, for example, lettuce or potato, when it is cheap, it is cheap. And everybody has it. Only potato, potato, potato.” Sara from Lacava says when there is a lot of competition, the local market price for milk drops. She thinks exporting is good because it helps their income: export milk “maintains the same price.”

Intermediaries

This unfavorable opinion of the local market has much to do with indigenous peasants feeling taken advantage of by local market intermediaries. It is not that they are not exploited in other markets, but it is not so obviously visible; in the local market they literally see the middleman turn around and sell it to someone else right away for more money. They feel they do not get a fair price because (1) the intermediaries profit more than they do; (2) the prices fluctuate and they never know what the local market price will be; and for quinoa farmers, (3) the intermediaries rob them, rigging the scales to pay less than they owe.

“Like all products, the national price is lower,” Octavio from Lacava tells me. Before the community had a centro de acopio (milk collection center), the dairy farmers in Lacava would sell their milk to intermediaries that drove through the community to buy their milk and re-sell elsewhere to fabricas (processing plants). The intermediary would buy the milk for 13, 14, or 15 cents and re-sell it for 25 cents. He profited at least 10 cents a liter on all the milk he bought from them. “The person who makes the money is the one who carries the milk to other places,” Octavio laments. Dairy farmers in Lacava now sell all their milk for a fixed price at the community centro de acopio. Diana thinks the centro de acopio helps a lot because before, with local market intermediaries, they were practically “giving the milk away for free.” What she cares the most about is that milk has a stable price. Before, they would never know what would happen with the price of milk. If they went out of town, when they got back, they could not guess what the price would be.

In Brocano, however, many farmers still sell their broccoli to local market intermediaries in addition to the community cooperative. They do this because the export cooperative does not buy all that they produce, so community members have extra broccoli to sell elsewhere. A 70-year-old man sitting at the base of the community in Brocano, waiting for a big truck to drive by and pick up his broccoli, tells me about his experience that week selling his broccoli harvest. “Every day the price changes. Wednesday was $4; Thursday was $3 and today is $2.50.” The comerciantes (local market intermediaries) have the power, he assures me. When he goes to the mercado mayorista (wholesale market) to sell sacks of broccoli, if he proposes a price of $5 a sack and the comerciante says “No, $2.50,” then they go with $2.50.

Quiloa farmers think the intermediaries rob them of their grains because they do not weigh honestly. Whether it is quinoa, barley, or wheat, Quiloa farmers complain about peso justo (fair weighing). Alongside precio justo (fair price), peso justo is just as important. When I asked Liana if there are also negatives, or only positives to selling quinoa to the exporter, she responded: “Only positives. Because they pay a fair price and they don’t rob you of pounds like in the plaza. In the plaza they rob you of a good part of your sack.” Cora also talks about being robbed of pounds. “In the plaza, they rob you. This time, they robbed me of four pounds.” She went to the weekly market with 30 pounds of quinoa; the first intermediary she went to weighed it as only 20 pounds, so she went to another and got $26 for it. That day, the local market price was $1 a pound, so she received $4 less than she thought was fair. Even though the local market price for quinoa at that time was high, she didn’t get as much money as she would have if she took the quinoa to the export organization which offers 90 cents a pound, but always weighs honestly.

These clear preferences persist despite some problems farmers have faced with export markets, and despite some advantages offered by local market intermediaries. The biggest problem that farmers have with their secure export links is delayed payment. Farmers in Quiloa, Brocano, and Lacava all complain that exporters do not pay right away. They have to wait weeks, even months, to receive their payment. This is frustrating for them, since they need the money right away to re-pay harvest expenses. Meanwhile, in the local market, they are paid immediately.

For broccoli and quinoa, while local prices fluctuate, the fluctuating price sometimes rises above the stable price offered by the exporter. For example, quinoa export NGOs buy quinoa for 90 cents a pound all year, while the local market price can reach up to $1.10 and as low as 50 cents a pound. The occasionally higher price offered by local market intermediaries can attract farmers to sell at least part of their export crop in the local market. Intermittent higher prices, paired with the immediate cash they receive from local intermediaries, lead broccoli and quinoa farmers to sell a portion of their output locally right after harvest. Still, the consensus remains: export markets are better because they offer a consistent price. As a follow up question to broccoli grower Alma, I asked “But in the national market, if intermediaries pay immediately, and if sometimes their price is better, why do you prefer to export?” She responds, “Yes, but exporting has a good price. It has a good price when the market here is low. When we deliver to export, it’s secure. The price is more secure.” Mariella agrees: “Because of the fixed price. Because in the plaza sometimes it rises, and sometimes it falls. Sometimes it is just low. There is no fixed price. But for exports, there is a fixed price.”

Thus, stability and trust in the intermediary are important considerations. Even if the local market price occasionally pays more, this benefit does not make up for long periods of low prices, or the uncertainty of frequent price fluctuation. Moreover, even if the intermediary says they will pay a given price, in practice they often pay less by claiming the farmer brought in less weight than they actually did. While export prices might occasionally be lower, at the least the farm trusts the intermediary to pay the promised price and weigh the product honestly.

Incentives

The current preference of campesinos to sell their commercial crops in export markets has to do with higher prices, more stable prices, and fairer commodity chains. In some cases, farmers also embraced incentives for healthier production practices. A few of the quinoa farmers in Quiloa (6 out of 38) said they prefer export markets because people in other countries value organic methods. I asked Fanny whether it is better to export quinoa or sell it in national market and her response was “We never use chemicals, only manure from our own animals.” I prompted her further about what that had to do with markets and she said “In the national market, it doesn’t matter if it’s chemical or organic, it doesn’t matter to them at all.” This shared value between themselves and northern consumers is not just about respect for environmental and human health, but also the premium price they pay for certified organic food. Julian thinks it is better to export quinoa because people in other countries pay more for organic certification. “One of the biggest problems,” he says, “is that Ecuadorians don’t care whether quinoa is organic or fair trade, but people in Europe and the US do, and so they pay more. Ecuadorians don’t want to pay more for certified.”

Farmers in the other two communities use chemicals in agricultural production, but they are torn about choosing between health and income, and ultimately make choices that improve their market position. Brocano and Lacava community members apply chemicals in order to meet quality standards and quantity expectations—blemish-free produce and plentiful supply of milk. The certified organic export market for quinoa offers a market incentive for indigenous farmers to use sustainable methods, while the milk and broccoli markets provide incentive for using (and becoming dependent on) agrochemicals. Some export markets value healthy and sustainable production methods and others do not, but none of the local markets offer higher prices for organic products.

Fair markets

Indigenous peasant farmers’ ideas for how to improve agriculture revolve around fairer markets and commodity chains, both local and export. They call for a fixed local market price that covers the cost of production; opportunities to export more of their crops; developing value-added products to export more directly; and government support in achieving these goals.

How could your experience with agriculture be improved? Flavio responds by saying: “Better markets. A fixed price, so it doesn’t rise, drop, rise, drop, but a fair price.” He is in favor of President Correa’s promise to set a minimum price on agricultural commodities so that the price is guaranteed to cover the cost of production. Gladys from Lacava tells me that it would be better if barley—the staple food crop she grows for consumption and occasional sale in the local market—had a fixed price. Why? “Because it would help us pay back what we invest. It would help us recover. Because sometimes you invest in production and then when it is harvest time, the price drops.” Why doesn’t she hold on to the harvest and wait for the price to increase? “Because I have to pay for the harvest machinery, and so I have to sell right away.”

One idea for making the local market more fair is to put in place fixed prices that the market cannot drop below even during harvest time when there is a lot of competition. Another idea is to organize and regulate planting so that overproduction does not occur at time of harvest. Ana from Quiloa tells me: “For us here in Ecuador, I think there is a lack of organization. For example, by zone. There are zones that grow beans and zones that grow vegetables. There are zones that grow only potatoes, only corn, only peas. I think this is a lack of organization. They have to organize, for example, the municipality, juntas parroquiales, the government itself, for us to have a just price.” As it is now, when there is any, there is lots, because of the similar production schedule between community members. Esteban from Brocano has a similar complaint and proposed solution:

Here in agriculture you have to plant thinking ahead, and plant orderly. Because, for example, one person plants lettuce – everybody plants lettuce. And what happens is the market price drops. I think it is better to analyze well what your neighbors plant to plant another thing to balance each other. If your neighbor plants lettuce, everybody plants lettuce. If your neighbor plants broccoli, everybody plants broccoli. What happens is the market drops to the ground. That’s what happens. There should be agricultural studies.

But most farmers do not want to wait for local markets to improve. They want a fair market price now, and for them, that means exporting. All three communities have “fair” links with the export organizations. Whether these organizations are for-profit firms in the case of milk and broccoli or non-profit development NGOs in the case of quinoa, each offers a stable price that remains constant. It does not change day-to-day like selling crops in the local market. Campesinos in all three communities expressed interest in exporting more products, beyond broccoli, quinoa and milk.

The quinoa farmers in Quiloa are interested in exporting their other grains through organic certified markets. They want the export NGOs to purchase barley and wheat in addition to quinoa. Nelson from Lacava also wants to export staple grains. Embra in Lacava wants to export cuy (guinea pig, a regional delicacy), if the government could help her find a market. Many people in Brocano talk about exporting the other vegetables they grow, like carrots, onions and beets. Alma from Brocano wants to grow new “desconocido” export crops: “It would be better, I say, if other, new products came to the community, others like broccoli. We want the governments of other countries to demand other products, that the government here gives us other products, unknown products, like artichokes, asparagus.”

Just as Lacava has a collection center where all the community members bring their milk to sell to the national firm, Nelson is starting an initiative in the community to export grains through a centro de acopio. His idea of food justice is not to sell crops locally, but that they, the farmers—the small-scale, historically marginalized indigenous peasant farmers—be the ones who profit. Teresa also thinks the government should help them sell more products through agricultural centros de acopio instead of always looking for intermediaries to sell to, “because they [the intermediaries] always buy to profit themselves.” Octavio is in favor of exporting milk precisely because the agribusiness middleman they currently supply does not profit too much: they buy for 42 cents a liter and sell for 45, so it is fair in his opinion.

Even though Octavio recognizes that their current market link is more fair than before, he wants to eventually export directly, without going through the processing firm. Lacava community members have a generally favorable opinion of their buyer because they pay a fair and stable price, but they also want to be their own middlemen. Octavio, as well as Sara, Pulisa, and other community members, tell me of their plans to receive government support to upgrade their facilities so they can sell value-added products, like yogurt, cheese and canned milk, not just the raw material. Their first step is to sell these products in national supermarket chains and work towards an export market: “Of course, if we had the opportunity to export, that is a dream to 1 day export product from here to other countries, because here we have a large quantity of milk that we produce daily,” says Octavio. Pulisa says “It is our vision that all the milk we produce leaves for the exterior.”

A similar community enterprise is emerging in Brocano. Currently the community has their own centro de acopio to collect broccoli and sell collectively to an agribusiness firm. Their goal is to upgrade the facilities to process broccoli and other vegetables into ready-to-eat packages to sell to national and international supermarket buyers. And in Quiloa, campesinos have joined together with quinoa farmers in neighboring communities to sell directly to Fair Trade certified buyers in the US and Europe, under the SPPFootnote 5 label. Even though the exporter they previously supplied was a non-profit development NGO, farmers wanted more decision-making power. Despite Fair Trade certification, indigenous community leaders felt the white, urban professionals at the export NGO were excluding them as actors with a stake in the process. As a result, they formed their own cooperative enterprise, run by indigenous farmers, to export directly. In addition, quinoa farmers want to benefit from the value-added products made with the raw material they supply, such as quinoa pasta and cookies, and they want to employ their own sons and daughters at the processing plant. Quinoa farmers are currently in the process of building their own industrial facility to process quinoa raw material into quinoa flour and elaborated products.

These campesinos want to export, but they simultaneously want to have more control over the process. From yogurt in Lacava, to chopped broccoli in Brocano, to quinoa pasta in Quiloa, campesinos want to benefit from activities downstream the commodity chain by processing and directly exporting value-added products through community-based enterprises, eliminating intermediaries.Footnote 6

Discussion

This case study is consistent with Masakure and Henson’s (2005) findings that small farmers in Zimbabwe are primarily motivated to enter into contract relations with export firms to reduce market uncertainty and offer a guaranteed market. This study also provides empirical support for Burnett and Murphy’s (2014) argument that peasant farmers want more equitable access to global markets rather than opposing the global trading system.

One could argue that these findings are an artifact of a particular time, when export markets are booming. Perhaps the farmers feel the way they do because they have only supplied the international market under relatively favorable conditions rather than during slumps. It is true that quinoa farmers have enjoyed increasing prices over the last 15 years, thanks to expanding consumer demand. Perhaps they will feel differently if the price crashes or they cannot sell their harvest due to overproduction. Dairy farmers, too, may associate rapid decline in prices with selling to local intermediaries because in the time since they formed a cooperative to sell to the national firm, prices have held steady. However, broccoli farmers have sold to an agribusiness export firm for 20 years, and over that time have experienced a number of downturns. They are currently supplying their third firm, as the first two collapsed, causing considerable economic hardship. Most recently, in 2009, the agribusiness processing firm went bankrupt, not paying them for a shipment of broccoli and putting farmers in debt. Despite this misfortune, they still believe in the promise of the global market for providing a stable livelihood. In their view, one setback along the export commodity chain—due to poor management at the level of the national agribusiness firm—does not compare to the longstanding, systematic disadvantage in the local market.

The experiences and perceptions of peasant farmers in this study also highlight the importance of national agrarian policies that affect the domestic price of food—such as direct government procurement from small farmers and minimum–maximum price controls that stabilize the highly volatile local market price for food. As others have remarked, the state is the “elephant in the room” (Bernstein 2014; Clark 2015). Even Left and reformist governments in Latin America “historically have not been pro-peasant” (Clark 2015, p. 5). In its current post-neoliberal context, the Ecuadorian state is steps ahead of other national governments in terms of support for food sovereignty and small farm sector. Still, even Ecuador does not yet offer a favorable national market for peasants to orient themselves inward. In a recently published article on food sovereignty politics in Ecuador, Clark (2015, p. 5) recognizes “it is important to heed the call of other scholars who have argued that the FS proposal needs to be understood in [the] historical context…of agrarian political economy.”

Conclusion

Scholars sometimes depict peasant farmers as the antidote to agri-food globalization because they feed local populations (Rossett 2000; Borras et al. 2008). However, the structural inequality of national food markets and advantages offered by global commodity chains need to be taken into consideration. Peasants do not necessarily produce, or want to produce, for local consumption; if they have the opportunity to export products to the Global North, they will likely take advantage of it.

This paper calls into question some of the fundamental assumptions underlying the FSM. It should not, however, be read as a critique of FSM tactics or goals. These findings are useful for food sovereignty activists to understand potential barriers between platforms and constituents and respond to the interests of a growing population of export-integrated peasant farmers. This is especially relevant to scholar-activists such as Borras et al. (2008, p. 169) who “seek, from the standpoint of engaged intellectuals, to advance a transformative political project by better comprehending its [Via Campesina’s] origins, past successes and failures, and current and future challenges.” Accomplishing this, they say, entails “acknowledging contradictions, ambiguities and internal tensions” (169).

In order to achieve a more sustainable and socially just global food system, ideologies must come face-to-face with on-the-ground realities. At the same time, even if peasant farmers prefer export markets, long-distance trade does entail ecological strain and environmental inequality. It also sets aside the question of access to food for the urban poor. Therefore, it is important that the inequalities facing local markets and national food systems be addressed. Peasant farmer perceptions of fairness can and should be used to improve food systems.

Above all else, food sovereignty stands for “the right to define their own food and agriculture systems” (Via Campesina 2007). In this case, with these peasants, their voice is clear. Their priority is fair markets in which to sell their products. This does not necessarily entail export-oriented trade. As it currently stands, the export market is less exploitative. The local market is not fair—yet. The FSM, international organizations and national governments must continue to work toward making the food system—locally, nationally, and globally—more fair for small-scale peasant farmers.

Notes

La Vía Campesina is commonly referred to as Via Campesina in English-language publications.

In other work, I examine the question of how agro-ecological indigenous peasant farmers are. This article focuses on the question of international trade.

This literature also acknowledges disadvantages associated with fair trade certification, such as higher labor costs.

The names of all communities and community members have been changed to protect their confidentiality.

SPP stands for Símbolo de Pequeños Productores, or Small Producer Symbol. SPP is a new initiative emerging out of the fair trade movement, in order to distinguish small producers from the large, even corporate-owned, plantations who are now eligible for fair trade certification.

It should be noted that eliminating middlemen is indeed a principle of the food sovereignty movement.

Abbreviations

- FSM:

-

Food sovereignty movement

- UNCTAD:

-

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development

- SPP:

-

Símbolo de Pequeños Productores

References

Akram-Lodhi, A.H., and C. Kay. 2009. The Agrarian question: Peasants and rural change. In Peasants and globalization: Political economy, rural transformation and the agrarian question, ed. A.H. Akram-Lodhi, and C. Kay, 3–34. London: Routledge.

Bacon, C. 2005. Confronting the coffee crisis: Can fair trade, organic, and specialty coffee reduce small-scale farmer vulnerability in northern Nicaragua? World Development 33(3): 497–511.

Becker, M. 2013. The stormy relations between Rafael Correa and social movements in Ecuador. Latin American Perspectives 40(1): 43–62.

Bernstein, H. 2014. Food sovereignty via the ‘peasant way’: A skeptical view. Journal of Peasant Studies 41(6): 1031–1063.

Borras Jr, S.M., M. Edelman, and C. Kay. 2008. Transnational agrarian movements: Origins and politics, campaigns and impact. Journal of Agrarian Change 8(2): 169–204.

Bryceson, D. 2000. Peasant theories and smallholder policies: Past and present. In Disappearing peasantries? Rural labour in Africa, Asia and Latin America, ed. D. Bryceson, C. Kay, and J. Mooij, 1–36. London: Intermediate Technology.

Burnett, K., and S. Murphy. 2014. What place for international trade in food sovereignty? Journal of Peasant Studies 41(6): 1065–1084.

Cardoso, F.H., and E. Faletto. 1979. Dependency and development in Latin America. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Clark, P. 2015. Can the state foster food sovereignty? Insights from the case of Ecuador. Journal of Agrarian Change. doi:10.1111/joac.12094.

De Janvry, A. 1981. The agrarian question and reformism in Latin America. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

De Schutter, O. 2014. Promotion and protection of all human rights, civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights, including the right to development. United National General Assembly, Human Rights Council, Sixteenth Session. New York: United Nations.

Desmarais, A.A. 2008. The power of peasants: Reflections on the meanings of La Via Campesina. Journal of Rural Studies 24(2): 138–149.

Edelman, M. 2005. Bringing the moral economy back in…to the study of the 21st-century transnational peasant movements. American Anthropologist 107(3): 331–345.

Edelman, M., T. Weis, A. Baviskar, S.M. Borras Jr., E. Holt-Giménez, D. Kandiyoti, and W. Wolford. 2014. Introduction: Critical perspectives on food sovereignty. Journal of Peasant Studies 41(6): 911–931.

Escobar, A. 1995. Encountering development: The making and unmaking of the third world. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Finan, A. 2007. New markets, old struggles: Large and small farmers in the export agriculture of coastal Peru. Journal of Peasant Studies 34(2): 288–316.

Fischer, E.F., and P. Benson. 2006. Broccoli and desire: Global connections and Maya struggles in postwar Guatemala. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Fitting, E. 2011. The struggle for maize: Campesinos, workers, and transgenic corn in the Mexican countryside. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Frank, A.G. 1978. Dependent accumulation and underdevelopment. London: Macmillan Press.

Giunta, I. 2013. Food sovereignty in Ecuador: The gap between the constitutionalization of the principles and their materialization in the official agri-food strategies. In Paper presented at the international conference in Food sovereignty: A critical dialogue, September 14–15, Yale University, New Haven, CT.

GRAIN. 2013. Yet another UN report calls for support to peasant farming and agroecology: It’s time for action. Media release 23 September. http://www.grain.org/article/entries/4789-yet-another-un-report-calls-for-support-to-peasant-farming-and-agroecology-it-s-time-for-action. (Accessed 10 June 2015).

Jaffee, D. 2007. Brewing justice: Fair trade coffee, sustainability, and survival. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Jarosz, L. 2011. Defining world hunger: Scale and neoliberal ideology in international food security. Food, Culture & Society 14(1): 117–139.

Korovkin, T. 1997. Indigenous peasant struggles and the capitalist modernization of agriculture: Chimborazo, 1965–1991. Latin American Perspectives 24(3): 25–49.

Lawrence, G., and P. McMichael. 2012. The question of food security. International Journal of Sociology of Agriculture and Food 19(2): 135–142.

Masakure, O., and S. Henson. 2005. Small-scale producers choose to produce under contract? Lessons from nontraditional vegetable exports from Zimbabwe. World Development 33(10): 1721–1733.

McMichael, P. 2009. A food regime genealogy. Journal of Peasant Studies 36(1): 139–169.

McMichael, P. 2011. Development and social change: A global perspective, 5/e. Thousand Oak, CA: Sage.

McMichael, P. 2014. Historicizing food sovereignty. Journal of Peasant Studies 41(6): 933–957.

Republic of Ecuador. 2008. Constitution of the Republic of Ecuador. Georgetown University: Political Database of the Americas. http://pdba.georgetown.edu/Constitutions/Ecuador/english08.html. Accessed 10 June 2015.

Rossett, P. 2000. The multiple functions and benefits of small farm agriculture in the context of global trade negotiations. Development 43(2): 77–82.

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). 2013. Trade and environment review 2013: Wake up before it is too late: Make agriculture truly sustainable now for food security in a changing climate. Geneva: United Nations. http://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/ditcted2012d3_en.pdf (Accessed 10 June 2015).

Van der Ploeg, J.D. 2014. Peasant-driven agricultural growth and food sovereignty. Journal of Peasant Studies 41(6): 999–1030.

Campesina, Via. 2007. The international peasant’s voice. Jakarta: La Via Campesina.

Campesina, Via. 2014. La Via Campesina 2013 annual report. Harare: La Via Campesina.

Walsh-Dilley, M. 2013. Negotiating hybridity in highland Bolivia: Indigenous moral economy and the expanding market for quinoa. Journal of Peasant Studies 40(4): 659–682.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Jeff Haydu and Leon Zamosc for their feedback on this paper and guidance throughout the research process.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Soper, R. Local is not fair: indigenous peasant farmer preference for export markets. Agric Hum Values 33, 537–548 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-015-9620-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-015-9620-0