Abstract

New graduate veterinarians report differing experiences of the transition to practice. Some make a rapid transition to professional autonomy while others require prolonged and extensive support from their colleagues. Factors contributing to this variation are unclear. This study used phenomenography to analyse the conceptions of and approaches to veterinary professional practice (VPP) reported by new graduates in semi-structured interviews (n = 22). Quantitative statistical analysis was used to investigate links between the quality of graduates’ experiences and their achievement during a comprehensive final year internship programme. Strong associations were identified between the quality of graduates’ conceptions of and approaches to VPP. Links were also established between the quality of graduates’ conceptions of VPP and their performance in practice prior to graduation. The outcomes of this research can be used to improve teaching and assessment during final year internships and enhance graduate attribute statements for professional degree programmes. The results also indicate that student learning research methodologies can be used to evaluate the quality of graduates’ experiences in the workplace. This has implications for career outcomes research in a range of healthcare professions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The overarching goal of veterinary education is to prepare students for effective, long term and satisfying careers as successful veterinarians. Comprehensive final year internship programmes have been implemented in veterinary degrees internationally to help achieve this aim (see for example Farnsworth et al. 2008; Jaarsma et al. 2008; Smith and Walsh 2003; Walsh et al. 2001). These programmes are designed to develop the attributes required for graduates to make a rapid transition to independent practice after graduation. Surveys reveal that new graduates experience a varying period of adjustment before practicing effectively as entry level professionals (Heath 1997; Heath and Mills 1999; Riggs et al. 2001; Routly et al. 2002). This suggests that the quality of graduates’ transition to entry level professional autonomy may differ from that intended by veterinary educators. Efforts to address this variation are hampered by a lack of awareness from the graduate perspective of factors associated with early attainment of entry level professional autonomy in practice.

Research in a range of tertiary education disciplines has shown that the quality of students’ learning outcomes is linked to their experiences of learning (Biggs 2003; Marton and Booth 1997; Prosser and Trigwell 1999; Ramsden 2003). These relationships can be revealed by adopting the student perspective on learning during student learning research (Entwistle 1997; Prosser and Trigwell 1999). Key aspects of students’ experiences of learning include students’ conceptions of what they are learning about and approaches to learning (Marton and Booth 1997). Higher quality approaches to learning tend to be associated with richer quality conceptions of what is being learned and better course achievement (Crawford et al. 1994; Ellis et al. 2006; Marton and Booth 1997). The methodologies used in this study were designed to investigate whether similar relationships existed between key aspects of new graduates’ experiences of veterinary professional practice (VPP).

This research formed part of a broader study aimed at investigating relationships between students’ experiences of a comprehensive final year internship programme and the success of their transition to independent practice as entry level veterinarians. It used the principles and methodologies of student learning research to establish graduates’ perspectives on their experiences in the year following graduation. Phenomenography was used to explore the variation present in graduates’ conceptions of and approaches to VPP. Additional quantitative statistics were then used to identify relationships between the quality of these components of graduates’ experiences of VPP and achievement during the final year internship programme. This illuminated key factors associated with the extent of graduates’ transition to independent practice in the year following graduation.

Attributes required for effective professional practice as a veterinarian

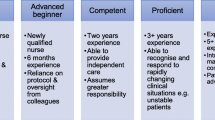

One of the main aims of veterinary education is to prepare students for working effectively in practice as autonomous professionals. Surveys of veterinary education stakeholders worldwide reveal common beliefs about the graduate attributes required for this goal to be achieved (Brown and Silverman 1999; Collins and Taylor 2002; Ontario Veterinary College 1996; Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons 2001). These aspects of veterinary professional practice can be grouped as shown in Fig. 1. Participation in comprehensive internship programmes during undergraduate studies is considered essential for development of effective practice in these areas.

Effective professional practice requires both ‘reflection-in-action’ and ‘reflection-on-action’ (Boud et al. 1985; Schön 1983, 1987). Reflection-in-action is characterised by critical evaluation of uncertain situations and careful reflection on options currently available for progress (Schön 1983). This is followed by thoughtful implementation of strategies to create new insight into the situation and proceed towards a solution (Schön 1983). Reflection-on-action is characterised by mentally returning to the experience after it has occurred to recall and detail specific events and feelings (Boud et al. 1985). The experience is then re-evaluated in light of the practitioner’s performance against their professional goals and a commitment to positive action is made (Boud et al. 1985). Internship programmes are designed to develop attributes associated with reflective practice by immersing interns in learning environments authentic to those encountered by new graduate veterinarians (Boud and Falchikov 2006).

Observations of the success of new graduates’ transition to professional autonomy

The transition between undergraduate studies and working independently in practice is challenging for many new graduate veterinarians (Heath 1997). Although some graduates demonstrate a rapid transition to professional autonomy, others require significant and prolonged support to meet the requirements of their role (Heath and Mills 1999; Riggs et al. 2001; Routly et al. 2002).

Surveys of veterinary employers consistently indicate that some new graduate veterinarians fail to meet expectations for performance in the workplace. New graduates are commonly perceived to have difficulty in astutely linking theoretical principles with relevant applications in practice and integrating the financial considerations of veterinary practice with clinical medicine (Heath and Mills 1999; Routly et al. 2002; Walsh et al. 2002). Some are also observed to struggle with aspects of client communication, self confidence and personal organisation (Heath and Mills 1999; Routly et al. 2002). These challenges can limit the profitability of practices that employ new graduate veterinarians (Routly et al. 2002).

Recently graduated veterinarians report similar perceptions of their professional practice. Deficits in clinical, financial, interpersonal, stress and time management skills are commonly mentioned (Heath 1997; Riggs et al. 2001). Of particular note is the difficulty new graduates describe in adjusting to the new level of professional responsibility that follows graduation (Heath 1997; Routly et al. 2002):

The first day? Well, I was more taken aback than I had expected. I thought it wouldn’t be any problem, but it’s very different going out and being confident as a student, to suddenly being in charge of whatever case you are looking at, and making the decisions. (Veterinary graduate; Routly et al. 2002, p. 168)

This study is designed to open new ways of understanding these findings by revealing factors associated with a successful transition to autonomous practice from the graduate perspective.

Phenomenography as a way of analysing variation in experience

Variation amongst a group of individuals in their experience of a phenomenon can be systematically analysed using phenomenography (Marton 1981; Marton and Booth 1997). This research method has been used extensively in higher education to reveal crucial differences in the quality of students’ learning experiences (Marton and Booth 1997; Prosser and Trigwell 1999). It is based on detailed analysis of students’ accounts of their learning experiences to identify the variation that exists amongst a group of learners (Marton and Booth 1997). This variation is captured in an outcome space that contains the minimum number of categories required to report the qualitative differences in students’ accounts of their experiences (Marton and Booth 1997; Prosser and Trigwell 1999). These ordered categories are linked in a logical relationship, commonly hierarchical, based on similarities and differences between the reports grouped in each category (Marton and Booth 1997). In student learning research, this form of systematic analysis allows judgements to be made about the quality of students’ learning (Marton and Booth 1997; Marton and Säljö 1976a).

Key aspects of learning about a phenomenon include students’ conceptions of what they are learning about and their approaches to learning (Marton and Booth 1997; Prosser and Millar 1989). The structure of the qualitatively different ways that university students understand what they are learning about is commonly described as being either fragmented or cohesive (Crawford et al. 1994; Marton and Booth 1997; Prosser and Trigwell 1999). Fragmented conceptions are characterised by awareness of few relationships between the parts of a phenomenon, and between these component parts and the whole phenomenon (Marton and Booth 1997). In contrast, cohesive conceptions are characterised by awareness of a range of interrelated parts of the phenomenon of interest, and diverse linkages between these and the whole phenomenon (Marton and Booth 1997). Inextricable relationships exist between these different structures of awareness and the different meanings attributed to the phenomenon (Marton and Booth 1997). Meanings associated with cohesive understandings of a phenomenon are more inclusive, more complex and more complete than those associated with fragmented conceptions of a phenomenon (Crawford et al. 1994; Marton and Booth 1997).

The qualitatively different ways that university students report approaching their learning are commonly described as surface and deep (Biggs 2003; Marton and Säljö 1976a). These different approaches have been shown to be associated with qualitatively different learning strategies and intentions. Surface approaches to learning have been linked with satisfying external expectations for performance by memorising and reproducing information perceived to be transmitted by experts (Biggs 2003; Crawford et al. 1994; Marton and Säljö 1976b). In some cases this includes memorising templates for expedient problem solving (Prosser and Millar 1989; Trigwell and Prosser 1991). Deep approaches to learning have been associated with intrinsic motivation to study and an intention to understand what is being learned (Biggs 2003; Prosser and Trigwell 1999). A more global and personal perspective on learning is evident, with new material being related to that which is already known and integrated into a unified whole (Crawford et al. 1994; Marton and Booth 1997; Svensson 1977). These qualitatively different types of strategies for learning have been described as atomistic and holistic respectively (Prosser and Trigwell 1999; Svensson 1977).

Logical relationships exist between the quality of students’ approaches to learning and their conceptions of what is being learned (Crawford et al. 1994; Prosser and Millar 1989). These are related to variation in the structure of students’ awareness. Surface approaches to learning tend to be linked to limited understandings of the material being studied, whereas deep learning approaches tend to be associated with more complete understandings of the material being studied (Prosser 2004). This is related to the observation that students adopting atomistic learning strategies delineate components of the phenomenon being learned about without regard to their underlying structure, whereas students adopting holistic learning strategies integrate and relate parts and relationships into a coherent understanding (Marton and Booth 1997; Svensson 1977). These general tendencies have been verified empirically in a range of higher education contexts (Crawford et al. 1994; Marton and Booth 1997; Prosser and Trigwell 1999) and are summarised diagrammatically in Matthew et al. (2010). This research project aims to establish whether similar relationships exist between graduates’ conceptions of and approaches to VPP. Quantitative statistical analyses are used to investigate associations amongst these components of students’ learning experiences and course achievement (Crawford et al. 1994; Ellis et al. 2006; Marton and Säljö 1976a; Prosser 1994).

Aims

This study seeks to provide detailed evidence from the graduate perspective of the variation that exists in experiences of VPP. It also seeks to identify associations between students’ performance during a final year internship programme and the quality of their professional practice as new graduate veterinarians. The hypothesis of this research is that variation exists in graduates’ experiences of VPP, and that this variation is foreshadowed by differences in achievement during a comprehensive final year internship programme. The following specific research questions are addressed in this research:

-

1.

What is the nature of professional practice for new graduate veterinarians who participated in a final year veterinary internship programme?

-

a.

What do these graduates think VPP is about?

-

b.

How do these graduates approach VPP? What do they do? and Why do they do it?

-

a.

-

2.

What associations exist between graduates’ conceptions of and approaches to VPP?

-

3.

How does variation in the quality of VPP experiences relate to student achievement during a final year internship programme?

Method

This study used phenomenography to investigate the variation that exists in new graduates’ conceptions of and approaches to VPP. Additional quantitative statistical analysis was then employed to reveal relationships amongst the quality of these aspects of graduates’ experiences in practice and achievement during a final year internship programme. The intention was to reveal the dimensions of entry level professional autonomy from the graduate perspective and their relationship to performance in practice during final year. The Human Research Ethics Committee of The University of Sydney approved the research (Project No. 8,025).

Context and participants

The context for this research was new graduates’ experiences of professional practice in Australian veterinary practices during the year following graduation from the Bachelor of Veterinary Science (BVSc) degree offered by The University of Sydney. The final year of the BVSc degree consists of a comprehensive veterinary internship programme. The population for this study was the cohort of final year interns (N = 100) progressing towards graduation from the BVSc degree in 2005. A fifth of this cohort (n = 22) participated in semi-structured interviews in the year after they graduated. Potential interviewees were identified based on their participation in earlier phases of the research (Matthew et al. 2010) and availability for being interviewed as new graduate veterinarians. The number of interviews was designed to enable a clear understanding of qualitative differences in new graduates’ experiences of VPP. Similar phenomenographic studies have demonstrated convincing findings using a sample size of approximately 20 interviews (Ellis et al. 2006; Martin et al. 2000; Prosser and Millar 1989; Prosser et al. 1994).

Instruments and analysis

Interview design and phenomenographic analysis

This investigation employed semi-structured interviews to provide detailed information about new graduates’ experiences of VPP (Crawford et al. 1994; Lindquist et al. 2006). Five main starting questions were used during each interview, two of which form the focus of this paper. Interviewees’ responses to the starting questions were probed with follow-up queries as appropriate to ask for more explanation, clarification of terms or a different view on the issue being discussed (Crawford et al. 1994). The starting questions were as follows:

-

1.

Thinking back on your work this year as a veterinarian, what is veterinary professional practice?

-

2.

Thinking back on your work this year as a veterinarian, how have you approached it? What have you done and why?

Phenomenographic analysis of graduates’ interview transcripts occurred through an iterative process involving three researchers with backgrounds in veterinary science and/or higher education. The transcripts were grouped by Researcher 1 into categories of similar responses detailing new graduates’ conceptions of and approaches to VPP. Brief descriptions of these categories were developed and illustrated with relevant interview extracts. These preliminary categories were discussed with the other researchers involved in this study and minor modifications were made. Detailed category descriptions were then completed by Researcher 1 and discussed with Researchers 2 and 3. Further modifications were made and final outcome spaces were developed for graduates’ conceptions of and approaches to VPP.

The success of this process is indicated by the percentage agreement between researchers for classification of a sample of interview transcripts (n = 5) against the categories resulting from this analysis (Säljö 1988). The average percentage agreement for graduates’ conceptions of VPP was 75% prior to consultation between researchers and 95% after consultation had occurred. Agreements of 65 and 85% before and after consultation respectively were established for graduates’ approaches to VPP. These are equivalent to those published in similar reputable studies (Ellis et al. 2006; Prosser et al. 1996; Säljö 1988; Trigwell et al. 1994; van Rossum and Schenk 1984).

Measures of achievement during the internship programme

The final year internship programme of the BVSc degree at The University of Sydney consists of 10 month long rotations located in a variety of veterinary work environments. Placement supervisors evaluate interns’ progress during each rotation towards the standards required for graduation using a Supervisor Report Form (SRF). The SRF assesses interns’ performance against a range of attributes considered essential for effective new graduate practice (Faculty of Veterinary Science 2009). SRF grades earned throughout final year were converted to numerical measures of achievement for the purposes of this study. Aggregation of these results created an overall measure of achievement, known as the aggregate SRF mark, for each participant in this research. Details of this process can be found in Matthew et al. (2010).

Quantitative analyses

Quantitative statistics were used to investigate links amongst graduates’ conceptions of VPP, approaches to professional practice and achievement during the internship programme. After phenomenographic analysis had been completed, frequency distributions were calculated for each category then grouped to reflect qualitatively different experiences of VPP. A Fisher exact procedure was used to investigate whether the quality of graduates’ conceptions of professional practice was related to the way they approached their work. Independent samples t tests and measures of effect size (ES) were used to explore associations between these components of graduates’ experiences and achievement during final year.

Results

The bulk of the research results presented in this paper reveal the variation present in graduates’ conceptions of and approaches to VPP. This is followed by additional quantitative analyses of relationships amongst these aspects of graduates’ experiences in practice and achievement during the final year internship programme.

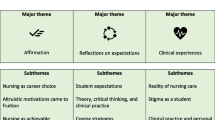

Conceptions of VPP

Categories for conceptions of VPP are distinguished by differences in emphasis in new graduates’ self reports about their understanding of professional practice. These characteristic emphases indicate variation in awareness of the complexity associated with working effectively as a veterinarian in practice. Four different ways of understanding VPP were identified. Responses included in all categories demonstrate dedication and commitment to serving society as a veterinary practitioner. They vary in the quality of understanding that is evident about what is encompassed in this role.

Category A responses focus on isolated elements of veterinary practice such as professional conduct, customer service and patient care. Few linkages are perceived between the elements of VPP that are discerned in this category:

Integrity. So doing the best that you can do. Unfortunately it seems to be more about talking to clients than even treating their animals. You need to keep up-to-date … Keeping the law.

Category B responses emphasise case management processes and protocols for interpersonal relationships in practice. These conceptions demonstrate limited awareness of the contextual variation relevant to professional decision making as a veterinarian:

I guess it involves a relationship with the client and their pet. So usually a client comes to you for something and you give your professional opinion on whatever it is. And that may or may not involve practical application of it, like surgery or something like that.

In contrast, Category C responses indicate rich, complex understandings of VPP that highlight interrelationships between many aspects of veterinary case and practice management relevant to new graduate practice. This demonstrates awareness of contextual variation in decision making that is in alignment with multiple stakeholder expectations for new graduate performance in practice:

I guess it’s a bit hard to get the balance right but you’ve got to uphold the views of your clinic and try and do what their practice policies are, but also try and act for the client’s benefit and the animal’s benefit. So you’ve got to try and incorporate all three.

Finally, Category D emphasises a personalised commitment to professional excellence as an essential component of successful VPP. Responses included in this category demonstrate advanced emotional intelligence and respect for the perspectives of others:

… doing the best for the client in terms of their position in life, their values, the money that they have available to them, while not compromising my own standards in terms of animal welfare and things like that. … I guess remembering why I became a vet in the first place … first and foremost, I do love animals.

Category D contains conceptions of professional practice that extend beyond those commonly expected of new graduate veterinarians in the year following graduation.

The categories for conceptions of VPP form a hierarchy with Category A on the bottom and Category D at the top. Category A represents the least inclusive and least complex conceptions of VPP contained in this hierarchy. Category D represents the most inclusive and most complex conceptions reported in this paper. The hierarchy is logically inclusive because the meaning attributed to VPP in higher categories encompasses the meanings associated with this phenomenon in lower categories (Crawford et al. 1994; Marton and Booth 1997). The hierarchy is empirically inclusive because graduates describing more comprehensive understandings of VPP also tended to describe components of the phenomenon characterising less complex conceptions of VPP (Crawford et al. 1994).

A qualitative shift occurs between Category B and Category C. Categories A and B display limited awareness of what is encompassed in professional practice and the relationships that exist between these aspects of a veterinarian’s role. Categories C and D demonstrate an understanding of the interwoven considerations for veterinary case management and practice that are relevant to professional decision making as a veterinarian. Adapting ideas from student learning research (Biggs 2003; Prosser 2004), this is consistent with a shift between multistructural and relational conceptions of VPP.

Approaches to VPP

Categories for approaches to VPP are distinguished by differences in emphasis that indicate varying levels of engagement in holistic professional practice. Five different ways of approaching professional practice as a veterinarian were identified from graduates’ interview responses.

Category A responses are characterised by reactive strategies that aim to meet minimum professional obligations and employment requirements:

Just show up and get thrown into consults. … Do my hours, do as little overtime as I can get away with, turn up for my after hours calls and things. … Getting things done so I can go home on time.

Category B responses focus on dealing expediently with veterinary cases throughout each day. This is achieved by quickly seeking guidance and following others’ instructions when non-routine cases are encountered:

So you have to force yourself to try and work things out, but you have to know when to ask for help, because if you wait too long then you’re just stuffing around and wasting time and probably going down the wrong track.

Category C is typified by enthusiastic involvement and full engagement in a wide range of cases. Increased case responsibility is accepted and reflection on case outcomes occurs to broadly improve professional abilities and enhance autonomy in entry level practice:

I’ve been pretty keen. Like really enthusiastic about all sorts of things. I’m pretty prepared to give anything a go. … I also follow up on cases … that furthers my own education and experience as well.

In Category D, professional challenges associated with working as a new graduate veterinarian are anticipated and managed to facilitate longevity in practice. A commitment is evident to reducing errors in professional judgement and overcoming negative aspects of practice:

I guess I’ve approached it from the point of view that I have strengths and weaknesses. And I build my confidence based on my strengths. And that confidence enables me to develop my weaknesses. … I’ve just had to keep telling myself that I have to make mistakes and that’s the way I’ll gain experience.

Category E responses describe identifying and applying holistic values to guide professional contributions. This is done to maintain consistency in behaviours, attitudes and values across personal and professional spheres of life:

… I think trying to be as understanding and compassionate and using that as the basis and hoping that everything comes from that. Trying to find a core value that would allow me to practice effectively and still have everything that’s expected financially, professionally, veterinary.

Categories C, D and E represent the type of high quality approach to VPP that is consistent with effective lifelong learning and long term success as a veterinarian in practice.

These categories form a hierarchy with Category A at the bottom and Category E on the top. Category A represents the least comprehensive approach to VPP and Category E represents the most comprehensive approach to professional practice as a veterinarian. A qualitative shift occurs between Category B and Category C. Categories A and B focus on using prescribed methods and protocols to meet external expectations for performance with minimum personal effort. In contrast, Categories C, D and E emphasise consistently reflecting on professional activities and outcomes to enhance autonomy and longevity in practice.

The hierarchy created by these categories of description is logically related, and empirically but not logically inclusive (Crawford et al. 1994; Marton and Booth 1997). This is because responses classified as consistent with higher quality approaches to VPP incorporate strategies and intentions typifying lower quality approaches to professional practice as a veterinarian. The hierarchy is not logically inclusive because an intention to only meet external expectations for performance is inconsistent with intrinsic motivation to consistently develop as a veterinary practitioner. Adapting terminology from student learning (Crawford et al. 1994) and reflective practice (Schön 1983, 1987), this is consistent with a dichotomy between formulaic and reflective approaches to VPP.

Quantitative analyses

Distribution of VPP conceptions and approaches

Just under half (46%) of the conceptions reported by new graduate veterinarians (n = 22) were classified as relational. Just over two-thirds (68%) of the reported approaches were classified as reflective. These results indicate that the majority of interviewees described approaches to VPP consistent with effective lifelong learning and successful practice as a veterinarian. Approximately half of the new graduates interviewed demonstrated awareness of the need to balance a range of stakeholder perspectives in high quality professional practice.

Relationships between VPP conceptions and approaches

Table 1 identifies relationships between aspects of new graduates’ experiences of VPP. A statistically significant relationship was revealed between the quality of conceptions of VPP and approaches to professional practice (phi = 0.62, p < 0.05). All of the graduates (n = 7) who reported adopting a formulaic approach to professional practice described conceptions of VPP that were classified as multistructural. All of the graduates (n = 10) who described relational conceptions of VPP reported approaches to professional practice that were classified as reflective. These results indicate that the quality of new graduates’ understanding of their role in practice is linked to the quality of the approach they adopt to their work.

Relationships between VPP conceptions, approaches and achievement during the internship programme

Table 2 relates the quality of VPP conceptions and approaches to achievement during final year as measured by aggregate SRF marks. It shows that graduates who described relational conceptions of VPP tended to have been assessed as performing at a higher level during final year than graduates who reported multistructural conceptions of VPP. This relationship was statistically significant and indicative of a large effect size (t = 2.4, p < 0.05, ES = 1.06). Graduates who adopted a reflective approach to professional practice tended to have been assessed as performing at a higher level during final year than graduates who reported an approach to VPP classified as formulaic (ES = 0.36). This relationship was not found to be statistically significant. These results suggest that student performance during a comprehensive final year internship programme is related to the quality of their professional practice in the year following graduation.

Discussion

This investigation aimed to establish the variation that exists in new graduate veterinarians’ experiences of professional practice, and investigate links to their performance in practice as students. Phenomenography was used for detailed exploration of graduates’ conceptions of and approaches to VPP. Associations between the quality of these aspects of graduates’ experiences and their achievement during a final year internship programme were evaluated using quantitative statistics. The results of these analyses need to be interpreted in the light of the specific context, researchers and participants involved (Marton and Booth 1997). The particular work environment that formed the context for this study needs to be taken into account when considering its relevance to the experiences of veterinarians in careers other than veterinary practice. The professional backgrounds of the researchers and new graduate status of the participants also need to be remembered when comparing the outcomes of this study to those arising from phenomenographic analysis of graduates’ experiences in other professions.

Factors contributing to the success of new graduates’ transition to independent practice

A key aspect of this study is the application of phenomenographic research methods outside the context of student learning. This has revealed the variation that exists in the quality of new graduates’ experiences of VPP. The different experiences of VPP reported by participants in this research can be summarised as shown in Fig. 2 (adapted from Crawford et al. 1994, p. 343).

This study illuminates key aspects of new graduates’ experiences of professional practice. Some graduates described experiences of practice that tended to overlook the broader ramifications of clinical decisions and relied on significant levels of support from more experienced colleagues. These descriptions indicate an incomplete transition to entry level professional competence and confidence after graduation. Other graduates described reflective approaches to practice that emphasised interwoven considerations for veterinary case and practice management. These types of experiences of VPP are consistent with attainment of entry level professional autonomy within a year of graduation. These accounts from graduates’ perspectives are consistent with observations by employers of variation in the quality of new graduates’ practice. They suggest that, for some graduates, the first year of work in practice is as much about continuing to learn and develop as a professional as it is about providing veterinary services as a contributing member of the veterinary profession (Heath 1997; Johnson and Andrews 2007; Smith 2008; Smith and Pilling 2007). This provides fresh insight into the observations of practitioners that some new graduates do not meet performance expectations, and the results of other investigations into veterinary education and the transition to practice (Heath 1997; Heath et al. 1996).

Graduates who reported higher quality conceptions of VPP tended to have been assessed as performing more successfully during final year than graduates who reported lower quality conceptions of VPP (p < 0.05). This suggests that achievement during comprehensive final year internship programmes can be used as an indicator of the likely quality of new graduates’ professional practice. Evaluating interns’ performance against criteria designed to reflect standards expected of new graduate veterinarians forms an effective way of predicting likely performance in practice after graduation. Assessment methods and criteria implemented during internship programmes can be aligned based on the results of this study to guide students more effectively and consistently towards entry level professional autonomy (Biggs 1996; Biggs and Tang 2007; Prosser and Trigwell 1999; Ramsden 2003).

Contributions to international benchmarks for veterinary graduate attributes

The outcomes of this research can be used to enhance graduate attribute frameworks currently used in veterinary education worldwide. Establishing a shared understanding of graduate attributes is crucial to attaining these outcomes through university studies (Barrie 2008). A holistic understanding of veterinary graduate attributes that encompasses graduates’ perspectives on professional practice enables educators to make more effective decisions on how these can be achieved (Barrie 2008). The analyses conducted during this research illuminate elements of VPP linked to high quality professional outcomes and a smooth transition to autonomous practice. This can be used to modify veterinary graduate attribute statements in ways that emphasise early attainment of professional autonomy. For example, relational conceptions of VPP revealed in this study can be used to highlight the complementary balance that exists between stakeholders’ needs in high quality professional practice. Similarly, reflective approaches to VPP reported in this research can be used to articulate the essential capacity for consistently reflecting on case outcomes as part of ongoing professional development. These attributes encompass and extend beyond those explicitly required for graduation from veterinary degrees. This helps to emphasise the nested relationship that exists between graduate attribute statements used to guide university studies and lifelong learning principles that guide continuing professional development throughout a successful veterinary career. Modifications based on similar research could be used to enhance the graduate attribute statements of other professional degree programmes.

Options for career outcomes research

This study demonstrates that the principles and methods of phenomenography can be productively applied to reveal factors related to the quality of graduates’ performance in practice. This has broad applications in career outcomes research for a range of professions. The detailed exploration of new graduates’ conceptions of and approaches to VPP conducted in this study complements and extends the results of previous surveys investigating veterinarians’ first years in practice and their subsequent career paths (Heath 1998, 2001, 2002, 2007). The outcomes of this research suggest that the quality of veterinarians’ conceptions of and approaches to VPP may make a vital contribution to enduring success and effectiveness as a veterinarian. Graduates reporting the highest quality experiences of VPP identified in this paper described a personalised commitment to professional excellence and/or application of holistic values to guide professional abilities. These experiences encompass elements of emotional intelligence and inspirational leadership, both of which have been proposed as being crucial for veterinary career success (Humble 2001). Longitudinal research would reveal whether reports of this type of experience are related to ongoing and outstanding contributions to society as new graduate veterinarians become more established in their careers. This has the potential to generate additional insight into the findings of studies linking veterinarians’ career satisfaction and longevity in practice with experiences of veterinary work during the new graduate period (Heath 1998, 2001, 2002, 2007). Similar studies could be conducted to investigate factors contributing to career success in other healthcare professions.

References

Barrie, S. (2008). Graduate attributes and career development learning. Preliminary discussion paper to the NAGCAS National Symposium, Melbourne.

Biggs, J. (1996). Enhancing teaching through constructive alignment. Higher Education, 32(3), 347–364.

Biggs, J. (2003). Teaching for quality learning at university: What the student does (2nd ed.). Berkshire, UK: Open University Press.

Biggs, J., & Tang, C. (2007). Teaching for quality learning at university (3rd ed.). Maidenhead, UK: McGraw Hill, Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University Press.

Boud, D., & Falchikov, N. (2006). Aligning assessment with long-term learning. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 31(4), 399–413.

Boud, D., Keogh, R., & Walker, D. (1985). Promoting reflection in learning: A model. In D. Boud, R. Keogh, & D. Walker (Eds.), Reflection: Turning experience into learning (pp. 18–40). London: Kogan Page.

Brown, J. P., & Silverman, J. D. (1999). The current and future market for veterinarians and veterinary medical services in the United States: Executive summary. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 215(2), 161–183.

Collins, G. H., & Taylor, R. M. (2002). Attributes of Australasian veterinary graduates: Report of a workshop held at the Veterinary Conference Centre, Faculty of Veterinary Science, University of Sydney, Jan 28–29, 2002. Journal of Veterinary Medical Education, 29(2), 71–72.

Crawford, K., Gordon, S., Nicholas, J., & Prosser, M. (1994). Conceptions of mathematics and how it is learned: The perspectives of students entering university. Learning and Instruction, 4(4), 331–345.

Ellis, R. A., Goodyear, P., Prosser, M., & O’Hara, A. (2006a). How and what university students learn through online and face-to-face discussion: conceptions, intentions and approaches. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 22(4), 244–256.

Ellis, R. A., Steed, A. F., & Applebee, A. C. (2006b). Teacher conceptions of blended learning, blended teaching and associations with approaches to design. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 22(3), 312–335.

Entwistle, N. (1997). Contrasting perspectives on learning. In F. Marton, D. Hounsell, & N. Entwistle (Eds.), The experience of learning: Implications for teaching and studying in higher education (2nd ed., pp. 3–22). Edinburgh: Scottish Academic Press.

Faculty of Veterinary Science. (2009). Veterinary graduate attributes—Future undergraduate students—The University of Sydney. Retrieved 18 Jan 2010, from The University of Sydney, Faculty of Veterinary Science Web site: http://www.vetsci.usyd.edu.au/future_students/undergraduate/graduate_attributes.shtml.

Farnsworth, C. C., Herman, J. D., Osterstock, J. B., Porterpan, B. L., Willard, M. D., Hooper, R. N., et al. (2008). Assessment of clinical reasoning skills in veterinary students prior to and after the clinical year of training. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 233(6), 879–882.

Heath, T. (1997). Experiences and attitudes of recent veterinary graduates: A national survey. Australian Veterinary Practitioner, 27(1), 45–50.

Heath, T. (1998). Longitudinal study of career plans and directions of veterinary students and recent graduates during the first five years after graduation. Australian Veterinary Journal, 76(3), 181–186.

Heath, T. (2001). Career paths of Australian veterinarians. Sydney: Postgraduate Foundation in Veterinary Science, The University of Sydney.

Heath, T. (2002). Longitudinal study of veterinarians from entry to the veterinary course to ten years after graduation: Career paths. Australian Veterinary Journal, 80(8), 468–473.

Heath, T. (2007). Longitudinal study of veterinary students and veterinarians: The first 20 years. Australian Veterinary Journal, 85(7), 281–289.

Heath, T., Lanyon, A., & Lynch-Blosse, M. (1996). A longitudinal study of veterinary students and recent graduates 3. Perceptions of veterinary education. Australian Veterinary Journal, 74(4), 301–304.

Heath, T., & Mills, J. N. (1999). Starting work in veterinary practice: An employers’ viewpoint. Australian Veterinary Practitioner, 29(4), 146–152.

Humble, J. A. (2001). Critical skills for future veterinarians. Journal of Veterinary Medical Education, 28(2), 50–53.

Jaarsma, D. A. D. C., Dolmans, D. H. J. M., Scherpbier, A. J. J. A., & van Beukelen, P. (2008). Preparation for practice by veterinary school: A comparison of the perceptions of alumni from a traditional and an innovative veterinary curriculum. Journal of Veterinary Medical Education, 35(3), 431–438.

Johnson, B., & Andrews, F. (2007). PDP: From pilot to practice. In Practice, 29(3), 166–169.

Lindquist, I., Engardt, M., Garnham, L., Poland, F., & Richardson, B. (2006). Physiotherapy students’ professional identity on the edge of working life. Medical Teacher, 28(3), 270–276.

Martin, E., Prosser, M., Trigwell, K., Ramsden, P., & Benjamin, J. (2000). What university teachers teach and how they teach it. Instructional Science, 28(5), 387–412.

Marton, F. (1981). Phenomenography—describing conceptions of the world around us. Instructional Science, 10(2), 177–200.

Marton, F., & Booth, S. (1997). Learning and awareness. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Marton, F., & Säljö, R. (1976a). On qualitative differences in learning: I—Outcome and process. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 46(Feb), 4–11.

Marton, F., & Säljö, R. (1976b). On qualitative differences in learning: II—Outcome as a function of the learner’s conception of the task. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 46(Jun), 115–127.

Matthew, S. M., Taylor, R. M., & Ellis, R. A. (2010). Students’ experiences of clinic-based learning during a final year veterinary internship programme. Higher Education Research and Development, 29(4), 389–404.

Ontario Veterinary College. (1996). Professional competencies of Canadian Veterinarians: A basis for curriculum development. Guelph, ON: University of Guelph.

Prosser, M. (1994). A phenomenographic study of students’ intuitive and conceptual understanding of certain electrical phenomena. Instructional Science, 22(3), 189–205.

Prosser, M. (2004). A student learning perspective on teaching and learning, with implications for problem-based learning. European Journal of Dental Education, 8(2), 51–58.

Prosser, M., & Millar, R. (1989). The “how” and the “what” of learning physics. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 4(4), 513–528.

Prosser, M., & Trigwell, K. (1999). Understanding learning and teaching: The experience in higher education. Buckingham, UK: SRHE and Open University Press.

Prosser, M., Trigwell, K., & Taylor, P. (1994). A phenomenographic study of academics’ conceptions of science learning and teaching. Learning and Instruction, 4(3), 217–231.

Prosser, M., Walker, P., & Millar, R. (1996). Differences in students’ perceptions of learning physics. Physics Education, 31(1), 43–48.

Ramsden, P. (2003). Learning to teach in higher education (2nd ed.). London: RoutledgeFalmer.

Riggs, E. A., Routly, J. E., Taylor, I. R., & Dobson, H. (2001). Support needs of veterinary surgeons in the first few years of practice: A survey of recent and experienced graduates. Veterinary Record, 149(24), 743–745.

Routly, J. E., Taylor, I. R., Turner, R., McKernan, E. J., & Dobson, H. (2002). Support needs of veterinary surgeons during the first few years of practice: Perceptions of recent graduates and senior partners. Veterinary Record, 150(6), 167–171.

Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons. (2001). Veterinary education and training: A framework for 2010 and beyond. London: Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons.

Säljö, R. (1988). Learning in educational settings: Methods of inquiry. In P. Ramsden (Ed.), Improving learning: New perspectives (pp. 32–48). London: Kogan Page.

Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Aldershot, England: Arena.

Schön, D. A. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Smith, C. S. (2008). A developmental approach to evaluating competence in clinical reasoning. Journal of Veterinary Medical Education, 35(3), 375–381.

Smith, R. A., & Pilling, S. (2007). Allied health graduate program—supporting the transition from student to professional in an interdisciplinary program. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 21(3), 265–276.

Smith, B. P., & Walsh, D. A. (2003). Teaching the art of clinical practice: The veterinary medical teaching hospital, private practice, and other externships. Journal of Veterinary Medical Education, 30(3), 203–206.

Svensson, L. (1977). On qualitative differences in learning: III—Study skill and learning. British Journal of Educational Psychology 47(Nov), 233–243.

Trigwell, K., & Prosser, M. (1991). Relating approaches to study and quality of learning outcomes at the course level. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 61(3), 265–275.

Trigwell, K., Prosser, M., & Taylor, P. (1994). Qualitative differences in approaches to teaching first year university science. Higher Education, 27(1), 75–84.

van Rossum, E. J., & Schenk, S. M. (1984). The relationship between learning conception, study strategy and learning outcome. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 54(Feb), 73–83.

Walsh, D. A., Osburn, B. I., & Christopher, M. M. (2001). Defining the attributes expected of graduating veterinary medical students. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 219(10), 1358–1365.

Walsh, D. A., Osburn, B. I., & Schumacher, R. L. (2002). Defining the attributes expected of graduating veterinary medical students, Part 2: External evaluation and outcomes assessment. Journal of Veterinary Medical Education, 29(1), 36–42.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are given to all the new graduate veterinarians interviewed during this project. Financial support was provided by the Faculty of Veterinary Science at The University of Sydney.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Matthew, S.M., Ellis, R.A. & Taylor, R.M. New graduates’ conceptions of and approaches to veterinary professional practice, and relationships to achievement during an undergraduate internship programme. Adv in Health Sci Educ 16, 167–182 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-010-9252-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-010-9252-5