Abstract

Agroforestry is a sustainable land management system that should be more strongly promoted in Europe to ensure adequate ecosystem service provision in the old continent (Decision 529/2013) through the common agricultural policy (CAP). The promotion of the woody component in Europe can be appreciated in different sections of the CAP linked to Pillar I (direct payments and Greening) and Pillar II (rural development programs). However, agroforestry is not recognised as such in the CAP, with the exception of the Measure 8.2 of Pillar II. The lack of recognition of agroforestry practices within the different sections of the CAP reduces the impact of CAP activities by overlooking the optimum combinations that would maximise the productivity of land where agroforestry could be promoted, considering both the spatial and temporal scales.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The common agricultural policy (CAP) is the most important driver of agricultural management and sustainability in the European Union. The CAP represents around 40% of the European Union (EU) budget, whose annual expenditure (in current prices) doubled from about EUR 30 billion in 1990 to EUR 60 billion in the CAP period 2007–2013. The European CAP has evolved from its initial inception in 1962 when it covered six countries. In 1973, the inclusion of the United Kingdom, Ireland, and Denmark increased this number to nine. Further additions were made in 1981 (10), 1986 (12), 1995 (15), and 2004 (25). The inclusion of Romania and Bulgaria in 2007 brought the total to 27, which finally amounted to 28 after the incorporation of Croatia in 2013, and which will return to 27 after the Brexit agreements. The CAP has now a direct impact on 14 million farmers, with a further 4 million people working in the food sector. One of the key CAP reforms occurred in 1992, when the ‘MacSharry’ reforms sought to limit the increasing cost of the CAP with a shift from product support (through prices) to coupled direct payments (through income support). The reforms also saw the reduction or complete removal of coupled payments, exports, refunds, and market support measures. The year 1992 also saw the introduction of the first directives that provided European support to the planting of forest trees on agricultural land. The Agenda 2000 reforms, signed in Berlin in 1999, emphasised the division of the CAP into a ‘first pillar’ based on single farm payments and a ‘second pillar’ focused on rural development measures. Following the CAP reform in 2003, payments were decoupled from the production of a specific product, while farmers would instead receive payments based on a set amount per hectare of agricultural land. The CAP has also aimed at becoming more environmentally oriented. For the 2007–2013 period, Pillar I across the EU-27 was worth just over three times the budget of Pillar II. However, differences existed between the CAP budgets for old and new Member States. Whilst the level of expenditure was relatively balanced in the 12 newest EU states (where the level of expenditure on both Pillars was almost the same), the EU-15 received five times as much for Pillar I than for Pillar II. For the 2014–2020 period, rural development and environmental issues will account to near 24% of the total CAP budget.

Nowadays, the CAP is designed to ensure food production within the sustainable FAO principles. The policy is written by the European Commission and has to be approved by the EU political bodies (Parliament and Council of Europe). Once approved, the CAP is implemented during a period of 7 years. The CAP is based on two main regulations, commonly called Pillar I and Pillar II, which were developed by Regulations 1307/2013 (EU 2013a) and 1305/2013 (EU 2013b) for the 2014–2020 commitment period. The global CAP budget is EUR 281.8 billion for the first pillar and EUR 89.9 billion for rural development (EU 2011). Pillar I is completely funded by the EU and initially linked to land productivity, while Pillar II is associated with the environment and co-funded by the Member States. Receiving support from any of the Pillars is conditional on the fulfillment of certain rules, termed Cross-compliance, which refers to minimum requisites on sustainability issues such as water quality and livestock health and welfare. Eligibility fulfillment rules in Pillar I are associated with the use of land for permanent grassland, and arable and permanent crops. The requisites for farmers to receive payments from Pillar II are established by each Member State based on their own interests from a productive and environmental point of view. Pillar II is composed of Regional and National Rural Development Programs that promote the environment but also the livelihood of farmers. This paper aims to analyse and explain the promotion of agroforestry practices within Cross-compliance, Pillar I, and Pillar II of the CAP at the EU level for the period 2014–2020.

Materials and methods

The analysis carried out in this paper is based on a literature review of the main CAP legislation framework for Pillar I (Regulation 1307/2013) (EU 2013a) and Pillar II (Regulation 1305/2013) (EU 2013b), as well as the accompanying and transposed legislation, such as Delegated Acts and 88 out of the 118 Rural Development Programs currently existing in the CAP for the period 2014–2020. Different documents and reports presented by the European Commission in the Civil Dialogue Groups and in the European Network for Rural Development from the European Commission web page were also evaluated thanks to the participation of the European Agroforestry Federation (EURAF, www.agroforestry.eu) in the meetings.

The paper analyses how the presence and management of woody vegetation is promoted within the current European CAP framework (period 2014–2020) extending beyond the agroforestry specific measure in Pillar II included in the CAP in 2007. Agroforestry promotion was evaluated in the different sections of the CAP whose fulfillment by farmers is required, such as (i) cross-compliance, whose rules have to be adopted as a prerequisite to get payments linked to Pillar I or Pillar II; (ii) direct payments that include eligibility and Greening measures within the norms required to receive support from Pillar I; and (iii) Pillar II. In all these sections, the CAP allows the selection of activities for implementation by the National Programs, which in turn develop strategies linked to the Partnership Agreement. The selected options may vary or are expanded as the CAP is implemented within a specific commitment period. The evaluation was carried with the available information up to year 2017.

Results

Agroforestry definition

Within the EU, Article 23 of Regulation 1305/2013 (EU 2013b) defines agroforestry systems as “land-use systems in which trees are grown in combination with agriculture on the same land”. However, woody perennials are considered by the European Commission in the application of Regulation 1305/2017, where Measure 8.2 (EU 2014a, b) defines agroforestry on agricultural land in the following terms: “Agroforestry means land-use systems and practices where woody perennials are deliberately integrated with crops and/or animals on the same parcel or land management unit without the intention to establish a remaining forest stand. The trees may be arranged as single stems, in rows, or in groups, while grazing may also take place inside parcels (silvoarable agroforestry, silvopastoralism, grazed or intercropped orchards) or on the limits between parcels (hedges, tree lines)”. The EU currently indicates that arable land, and therefore agroforestry on such land, is not be eligible for direct payments if it contains more than 100 trees/ha, as established by Regulation 640/2014 (Mosquera-Losada et al. 2016b), although it allows Member States to select tree densities below this maximum if local practices are implemented on permanent grassland. The focus on woody perennials was also part of the definition for agroforestry as used in the EU-sponsored AGFORWARD research project that ran from 2014 to 2017 (Burgess et al. 2015) and FAO (2017). ICRAF specifies that the concept of ‘trees’ is linked to woody perennials (therefore, ‘trees and shrubs’).

Cross-compliance

Farmers get paid the direct payments and Greening, as well as Pillar II funds, upon fulfilling the Statutory Mandatory Regulations (SMRs) and Good Agricultural and Environment Conditions (GAECs), generally known as Cross-compliance (conditionality). SMRs refer to EU Directives and Regulations linked to public, animal, and plant health, identification and registration of animals, and environmental and animal welfare. Agroforestry is able to directly fulfill the first three measures (nitrate vulnerable zones and biodiversity dealing with birds and habitats) of the SMRs, but the rest may also be improved by sustainable agroforestry practices (e.g. the quality of feed and food).

The GAECs within the period 2014–2020 currently include options related to water and soil and carbon stocks, where agroforestry can play a role as a sustainable agricultural practice as per GAEC 7, linked to the retention of landscape features. Landscape features include woody vegetation such as hedges and trees in line, in groups, or isolated which are directly related to agroforestry practices, among other features such as ponds, terraces, and field margins (Santiago-Freijanes et al. 2018). The agroforestry practices linked to GAEC 7 are of high interest in some countries as they avoid problems related to winds or flooding and enhance the biodiversity.

Pillar I

Direct payments

CAP establishes three different types of land for the evaluation of their suitability to receive basic payments and Greening through eligibility: arable land, permanent grassland or permanent pasture, and permanent crops.

Arable lands

The eligibility of arable lands is limited by the Delegate Act 640/2014 (EU 2014a) to those lands with a tree density below 100 trees/ha. This specific constraint makes it difficult for farmers to introduce trees on their arable land, in particular when they own small plots. The conditions for those trees, defined as isolated trees, are provided in the Delegated Act 639/2014 (EU 2014b) as those with a minimum crown diameter of 4 m, which means a tree cover of 1256 m2/ha (12.56%) when considering the 100 trees/ha rule. If trees are grouped, the maximum area allowed for woody vegetation is even lower, as the CAP allows the 10% of the hectare (1000 m2/ha) to get paid. Regarding hedges or hedgerows, the regulation protects those already existing with a width of up to 10 m (Regulation Act 639/2014 (EU 2014b)), but only those with a 2-m width can be claimed as eligible land for payment even if the Member State protects wider hedges (DEFRA 1997).

Permanent grassland or permanent pasture

Following the definition given in Regulation 1307/2013 (EU 2013a), permanent grassland or permanent pasture refers to “land used to grow grasses or other herbaceous forage naturally (self-seeded) or through cultivation (sown) and that has not been included in the crop rotation of the holding for 5 years or more; it may include other species such as shrubs and/or trees which can be grazed provided that the grasses and other herbaceous forage remain predominant as well as, where Member States so decide, land which can be grazed and which forms part of Established Local Practices (ELPs) where grasses and other herbaceous forage are traditionally not predominant in grazing areas”. This can therefore include agroforestry as woody vegetation is admitted, for which no predominant herbaceous grasslands can claim full payment if ELPs are selected by the European Member States. Countries that have active ELPs, and therefore payments for non-predominant herbaceous permanent grasslands, are Germany, Spain, Sweden, Greece, France, Hungary, Italy, Cyprus, Portugal, and United Kingdom. However, all non-predominant herbaceous permanent grasslands may be able to claim full payment if grazed thanks to the implementation of the OMNIBUS Regulation in 2018 (European Council 2017).

Permanent crops

Permanent crops are defined by the Commission as non-rotational crops other than permanent grassland that occupy the land for 5 years or more and yield repeated harvests, including nurseries and short rotation coppice. For permanent crops, the tree densities set for arable land eligibility do not apply and combinations with crops are allowed. If fruit trees are combined with grazing, this type of land exploits gaps in the silvopasture concept and again, no restrictions on the fruit tree density apply. Permanent crops are those listed in Annex 1 of Regulation 1308/2013, including apple, pear, apricot, peach, nectarines, orange, small citrus, lemon, and olive trees, as well as vineyards for table production as the woody component.

Greening

Greening refers to payments for agricultural practices beneficial for the climate and environment, which, as part of Pillar I payments, represent 30% of the direct payment value received by farmers. Greening, as occurs with cross-compliance, includes landscape features as an option for farmers to fulfill its requirements, but also gives the option of choosing agroforestry. At least one type of landscape feature has been initially selected by 24 Member States; however, this does not imply that trees in line, copses, or isolated trees have been selected, which hampers the evaluation of the impact of the Greening measure. This is because landscape features include other options, such as ponds, terraces, and field margins that are not related to woody vegetation. Moreover, even if countries have made an initial selection, they may not activate it during CAP implementation.

Unfortunately, Greening only affects 40% of the direct payment beneficiaries in Europe, mainly due to the small size of the farms, which receive Greening payments per se. The percentage of the total agricultural area subjected to at least one Greening obligation (crop rotation, permanent grassland preservation, and Ecological Focus Areas) is lower in Southern (Greece, Italy, Malta, or Portugal) than in Northern European countries such as Germany or Latvia. The most selected option of Ecological Focus Areas (EFAs) by the EU Member States is nitrogen-fixing crops (35–46%), followed by catch crops (15–27%), and fallow land (21–35%), which represent 94% of the area fulfilling the EFAs requirements. The selection of any of these three options, among others including agroforestry, is likely due to them being the easiest to implement by farmers. Agroforestry has not been implemented yet and landscape features are only used in around 4.34% of the land claiming Greening support. A greater diversification of the farmers’ EFA choices is expected in the forthcoming years and, hopefully, woody vegetation will be more widely used.

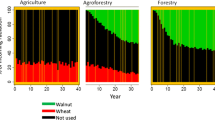

Pillar II

Table 1 shows the measures promoting the woody component in agricultural land and the agricultural activity linked to the woody component in the evaluated rural development programs of the EU, while Fig. 1 presents the number of measures linked to agroforestry implemented in the evaluated EU regions. Most of the CAP 2014–2020 programs were approved during 2015, and thus had only been partially implemented in 2016. To carry out this evaluation, we read the 88 Rural Development Programs (RDPs) implemented in Europe and organised them based on the activities they finance that are linked to agroforestry practices (silvopasture, silvoarable, forest farming, riparian buffer strips, and homegardens). The selected activities include those associated with forest farming agroforestry practices (apiculture), those increasing the woody vegetation across Europe (forest strips and small stands, hedgerows, isolated trees), those dealing with permanent crops of fruit trees (orchards) and, finally, those related to silvopasture (forest understory grazing and mountain silvopastoralism). Twenty-three measures have been established in Europe that can be associated with agroforestry within the RDPs framework, but they do not mention agroforestry or any of its practices in a specific way, with the exception of Measure 8.2 out of all the RDPs measures of the CAP 2014–2020. From those, the measure that mostly supports agroforestry is the agri-environment measure (Measure 10.1). Hedgerow (woody component) establishment and management is the most extensively promoted measure linked to agricultural land out of the vast number of measures used across Europe, while meadow orchards have been implemented in most regions by one single measure. The specific agroforestry Measure 8.2 was intended for use in only 33 out of the 88 evaluated regions, a number that will probably increase in the forthcoming years. In the first year, only five RDPs implemented the measure out of the 16 that activated it, mainly through activities related to the establishment and management of forest strips, small stands, hedgerows, and forest grazing.

Discussion

Understanding the impact of the CAP and specifically of agroforestry on European lands is difficult due to several reasons, such as (a) the capacity of countries to choose between different options within the CAP, (b) the variety of options regarding the implementation period, which is typically 7 years, (c) the different environmental and socioeconomic situation of the Member States, and (d) the varying number of EU countries implementing the CAP, which has increased in the last years, affording different degrees of adaptation to said policy. The selection of the CAP alternative measures by each Member State delays usually the start of the CAP implementation by 1 or 2 years. Member States have to construct their own CAP based on the EU CAP framework and choose among the different alternatives in order to adapt the CAP to their own requirements and environments, which is a really important aspect for agricultural sustainability. Furthermore, accountability as well as modification of the CAP rules is always complicated. Moreover, the CAP selection may be modified by Member States during the commitment period, and it is usually reviewed and strongly modified at mid-term with important changes, making the evaluation of the global period extremely difficult. For example, the implementation of Pillar I of the 2014–2020 CAP started at the beginning of 2015, with an extension of the CAP 2007–2013 in 2014, while most RDPs set up their initial choices at the end of 2016, after which farmers could start to meet the requirements to receive support.

Regarding the difficulties agroforestry practices present for promotion at the European scale, several deserve to be mentioned in particular. The FAO (2015) define agroforestry as “a collective name for land-use systems and technologies where woody perennials (trees, shrubs, palms, bamboos, etc.) are deliberately used on the same land-management units as agricultural crops and/or animals”. In North America, AFTA (2016) defines agroforestry as “an intensive land management system that optimizes the benefits from the biological interactions created when trees and/or shrubs are deliberately combined with crops and/or livestock”, and USDA (2017) “Agroforestry is the intentional integration of trees and shrubs into crop and animal farming systems to create environmental, economic, and social benefits”. The inclusion of ‘woody perennials’ in the definition of agroforestry in the current CAP (2014–2020) compared to the previous period (CAP 2007–2013), rather than exclusively ‘trees’, facilitates the sustainability and adaptation of farming systems to the existing different environments in the EU countries in the form of shrubs owing to their woody perennial nature, providing many of the same productive, environmental, and/or social benefits of trees (Mosquera-Losada et al. 2006; Rigueiro-Rodríguez et al. 2009). Moreover, tree definitions vary across countries, and trees can also be cultivated in shrub form while providing the same environmental and social benefits (Mosquera-Losada et al. 2016a).

The current CAP definition of agroforestry applied in Measure 8.2 is adequate, but we argue that the inclusion of a two-layer concept can help to avoid confusion, for example in the case of using fruit trees when the crop is on the tree. Thus, the AGFORWARD project has proposed the following definition: “the deliberate integration of woody vegetation (trees and/or shrubs) as an upper storey on land with pasture (consumed by animals) or an agricultural crop in the lower storey. The woody species can be evenly or unevenly distributed or occur on the border of plots. The woody species can deliver forestry or agricultural products and other ecosystem services (i.e. provisioning, regulating or cultural)” (Mosquera-Losada et al. 2017). Moreover, difficulties exist to clearly identify the different types of agroforestry practices (silvopasture; silvoarable; hedgerows, windbreaks and riparian buffer strips; forest farming, and home gardens) within the Pillar I regulation description, which are typically referred to by local names (e.g. grazed orchards, wood pastures, dehesa, montado, parklands, hedges) but not clearly identified as agroforestry.

Den Herder et al. (2017) and Mosquera-Losada et al. (2016c) which considered exclusively the tree components (excluding shrubs) and woody components (trees + shrubs), respectively, are the first systematic studies to identify the extent and location of agroforestry use and practices in Europe. However due to the lack of data, researchers are not currently able to identify which of these agroforestry practices are linked to CAP payments. The first step to improve the agroforestry policy in Europe is to identify the land where it is applied and how the policy modifies its implementation to create tailor-made agroforestry practice measures according to the needs of specific regions and the ecosystem services they should deliver. Cross-compliance deals with measures for already existing woody components in arable and pasture lands, but not with the enhancement or real promotion of them. The extension of agroforestry practices should be based on a more flexible strategy pursuing the generation of products from woody vegetation while implementing sustainable practices using circular economy and bioeconomy approaches. In general, and when considering the eligibility of an arable land, at present no more than 10% of the arable land is allowed to have an already existing woody component, a number that has been increased from the last CAP 2007–2013, where only a 5% was allowed. However, these rules are still not enough to ensure the productivity and resilience of European arable systems since the tree density does not correlate with the concept of ‘mature tree’ and most Member States take this density as a limit for any new tree plantation in the European Union. Crown diameters of over 4 m can be considered in most cases mature trees, and trees with diameters smaller than 4 m are not protected even if they are essential to ensure the long term sustainability of isolated trees. The 50 and 100 trees/ha limit given for arable land in the previous (2007–2013) and current (2014–2020) policies, respectively, have caused the destruction of trees, mostly in small plots of farms, in both already land receiving Pillar I payments and on land that farmers are intending to include for future CAP support. Hedgerows larger than 2 m are not generally considered eligible by the EU, even if they are protected, which makes farmers associate them with a reduction of the CAP support, despite the ecosystem services they deliver, and farmers may reduce their size if not destroy them all together. By contrast, alley cropping or silvoarable practices with short rotation coppices are allowed and fully eligible in the current CAP, but they are not promoted or even specifically mentioned. The woody vegetation of permanent pasture has been protected to some extent in those countries where ELPs are applied. However, some countries have decided not to make eligible pastures dominated by woody vegetation by not widening the ELP options, limiting the positive effect that woody vegetation could have for animal feeding during the drought period of the summer. This may change with the implementation of the OMNIBUS Regulation (European Council) in 2018.

Another aspect that undermines the use of woody vegetation in the CAP is that it does not consider the form and the function of that vegetation; instead the assumption is that the reduction in agricultural activity is solely dependent on the tree density. The tree density criterion has at least three main drawbacks. The first one is that the limiting factor for radiation to reach the understory is not the tree density but the tree coverage, which can nowadays be easily measured using satellite images but that is not considered by the CAP. The second drawback is related to the general assumption that the reduction of radiation necessarily reduces the understory production. In practice, some crops adapt and are more efficient under shade conditions, even increasing their productivity (i.e. the production of the active principle rosmarinic acid extracted from Melisa officinalis L. is increased in the shade because its maximum productivity and quality is linked to the flowering period, which is delayed in the shade, therefore increasing the active principle production per unit of land). In this regard, genetic selection of crop varieties able to remain productive under shade conditions should be developed, as most varieties already existing in the market have been selected for open conditions. The third drawback of the tree density criterion is the lack of a link between the tree density and the temporal dimension. In some areas, such as the dehesa in Spain, the presence of trees in a plot extends the growing season during droughts and extreme heat, and this mitigates the impact of the reduction in solar radiation (García de Jalón et al. 2018). This is important for the adaptation of agricultural systems to climate change (Sciences Vie 2015).

The current permanent pasture definition indeed recognises all types of permanent grasslands across European biogeographic regions better than the previous CAP, in which it was only associated with herbaceous grasslands. Thanks to the inclusion of the concepts of “self-seeded” (annual herbaceous species) and “grasses and other herbaceous forage traditionally not predominant in grazing areas”, ecological traits linked to species evolution strategies to survive deficient periods (summer) or disturbances (i.e. heavy rains and floods) are included, making the ecosystems more resilient to droughts and heavy rainfall, and able to avoid erosion. However, when a Member State decides to apply a pro-rata system (meaning that the surface of the woody component in permanent grassland is discounted for farm payments), it is applied to all permanent grassland parcels of the Member State or region territory with scattered ineligible features. This choice means that previously ineligible areas smaller than 1000 m2 are now eligible; unfortunately, this is applied at the parcel level (not per hectare) and therefore the eligibility depends on the parcel size. Farms with large parcels, even those extending several hectares, are only allowed to have 1000 m2 of woody vegetation. Another problem for agroforestry is the interpretation of the concept of ‘grazable trees’ in permanent grassland. As the EU (2015) indicates, ‘grazable trees’ on permanent grasslands, which are considered part of the eligible area, should not be accounted for when assessing whether the parcel is below or above the maximum tree density. However, the concept of ‘grazable trees’ for the European Commission refers to those features ‘that can be grazed’ and should be actually directly accessible to farm animals for grazing of their full area. This implies that the animals must access the food directly from the trees, rendering ineligible and therefore not counting those trees that have been planted in a plot to provide fruit to animals during the fruit drop season (i.e. Quercus ilex in dehesa systems).

Regarding Pillar II, most regions of Europe have activated the promotion of new and/or adequate management of hedgerows and isolated trees with at least one measure. It is important to highlight that the most popular rural development measure (Measure 10.1), the so-called Agri-environment climate commitments (AECMs), recognises the role of woody vegetation in Europe for environmental improvement and the reduction of negative climate change impacts. The lack of recognition of agroforestry in different measures of the CAP, even though the woody component is somehow promoted, reduces the impact of agroforestry practices, since the connection between the crop or pasture and the tree to improve the productivity and the selection of best species or varieties of both components to achieve enhanced productivity in a specific land is not pursued. The visibility of agroforestry should be clear, mostly for the accomplishment of Decision 529/2013 (EU 2013c) regarding the mitigation and adaptation to climate change. However, the specific agroforestry measure (Measure 8.2) has had a low degree of implementation in most European Union regions. Some of the justifications for this fact are: (a) the implementation of agroforestry practices under Measure 8.2 may contribute to the loss of direct payments for specific plots (Mosquera-Losada et al. 2016c), thus stopping farmers from applying them due to the lack of an adequate link between Pillar I and Pillar II; (b) the lack of knowledge on how to better integrate the woody and agricultural components to increase productivity; (c) the lack of a market for the woody or agricultural components perhaps linked to an ‘agroforestry label’, allowing farmers to obtain benefits from such a more sustainable use of the land; and (d) the lack of payment to farmers for ecosystem services or environmental results.

Nowadays, the EU is aware of the huge existing gap between knowledge and implementation, and has thus created European Innovation Partnerships as a new horizontal approach within the RDPs. A large amount of money has been allocated to operational groups who can undertake different activities where farmers can discuss and develop sustainable practices and within these agroforestry can play an important role. Moreover, the Commission also supports the creation of transnational Focus Groups, where researchers and practitioners are able to discuss specific subjects of interest to the Operational Groups. During 2017, the European Agroforestry Federation supported the Agroforestry Focus Group by providing information, future research directions, and identifying problems that need to be solved to increase the extent and recognition of agroforestry in Europe (Agroforestry Focus Group 2017).

Conclusions

There is clear recognition of the woody component within the CAP but there is minimal overall appreciation of agroforestry. Such a lack of recognition is undermining the flexibility of farmers to pursue the best combinations between the woody component and the agricultural activity from the understory at a range of spatial and temporal scales. We strongly recommend the recognition of agroforestry and agroforestry practices as such through the whole CAP and agroforestry practices that provide wider environmental and social benefit should receive full Pillar I payments on agricultural lands.

References

AFTA (Association for Temperate Agroforestry) (2016) What is Agroforestry? http://www.aftaweb.org/about/what-is-agroforestry.html. Accessed 27 Mar 2017

Agroforestry Focus Group (2017) Agroforestry: introducing woody vegetation into specialised crop and livestock systems. https://ec.europa.eu/eip/agriculture/en/content/agroforestry-introducing-woody-vegetation-specialised-crop-and-livestock-systems. Accessed 27 Mar 2017

Burgess PJ, Crous-Duran J, den Herder M, Dupraz C, Fagerholm N, Freese D, Garnett K, Graves AR, Hermansen JE, Liagre F, Mirck J, Moreno G, Mosquera-Losada MR, Palma JHN, Pantera A, Plieninger T, Upson M (2015). AGFORWARD Project periodic report: January to December 2014. Cranfield University: AGFORWARD. http://www.agforward.eu/index.php/en/news-reader/id-27-february-2015.html. Accessed 16 Mar 2018

DEFRA (1997) Hedgerow regulation. http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/1997/1160/regulation/6/made. Accessed 27 Mar 2017

den Herder M, Moreno G, Mosquera-Losada MR, Palma J, Sidiropouloue A, Santiago Freijanes JJ, Crous-Duran J, Paulo JA, Tomé M, Pantera A, Papanastasis VP, Mantzanas K, Pachana P, Papadopoulos A, Plieninger T, Burgess PJ (2017) Current extent and stratification of agroforestry in the European Union. Agric Ecosyst Environ 241:121–132

EU (2011) Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the council, the European economic and social committee and the committee of the regions. A budget for Europe 2020. http://poalgarve21.ccdralg.pt/site/sites/poalgarve21.ccdralg.pt/files/20142020/4_ficheiro_d_budget_for_europe_2020.pdf. Accessed 27 Mar 2017

EU (2013a) Regulation (EU) No. 1307/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council establishing rules for direct payments to farmers under support schemes within the framework of the common agricultural policy and repealing Council Regulation (EC) No. 637/2008 and Council Regulation (EC) No. 73/2009. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2013:347:0608:0670:en:PDF. Accessed 27 Mar 2017

EU (2013b) Regulation (EU) No 1305/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 December 2013 on support for rural development by the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD) and repealing Council Regulation (EC) No 1698/2005. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2013:347:0487:0548:en:PDF. Accessed 27 Mar 2017

EU (2013c) Decision No 529/2013/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 May 2013 on accounting rules on greenhouse gas emissions and removals resulting from activities relating to land use, land-use change and forestry and on information concerning actions relating to those activities. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32013D0529. Accessed 27 Mar 2017

EU (2014a) Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) No 640/2014 of 11 March 2014 supplementing Regulation (EU) No 1306/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council with regard to the integrated administration and control system and conditions for refusal or withdrawal of payments and administrative penalties applicable to direct payments, rural development support and cross compliance. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg_del/2014/640/oj. Accessed 27 Mar 2017

EU (2014b) Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) No 639/2014 of 11 March 2014 supplementing Regulation (EU) No 1307/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council establishing rules for direct payments to farmers under support schemes within the framework of the common agricultural policy and amending Annex X to that Regulation. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN-ES/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32014R0639&fromTab=ALL&from=en. Accessed 27 Mar 2017

EU (2015) Guidance document on the land parcel identification system LPIS under articles 5, 9 and 10 of Commission Delegated Regulation EU number EU NO 640/2014. https://marswiki.jrc.ec.europa.eu/wikicap/images/4/4b/DSCG-2014-31_EFA-layer_FINAL-2015.doc.pdf. Accessed 27 Mar 2017

European Council (2017) OMNIBUS Regulation draft. http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/cap-simplification/omnibus-regulation-agriculture/. Accessed 11 Aug 2017

FAO (2015) FAO projects. http://www.fao.org/forestry/agroforestry/90030/en/ and http://www.fao.org/3/a-i3182e.pdf. Accessed 27 Mar 2017

FAO (2017) Agroforestry definition. http://www.fao.org/forestry/agroforestry/80338/en/. Accessed 15 Dec 2017

García de Jalón S, Graves A, Moreno G, Palma JHN, Crous-Durán J, Kay S, Burgess PJ (2018) Forage-SAFE: a model for assessing the impact of tree cover on wood pasture profitability. Ecol Model 372:24–32

Mosquera-Losada MR, McAdam J, Rigueiro-Rodríguez A (2006) Silvopastoralism and sustainable land management. Cab International, Oxfordshire

Mosquera-Losada MR, Santiago-Freijanes JJ, Pisanelli A, Lamersdorf N, Burgess P, Fernández-Lorenzo JL, González-Hernández P, Ferreiro-Domínguez N, Rigueiro-Rodríguez A (2016a) Agroforestry in the CAP: eligibility. 3rd European Agroforestry Conference, Montpellier, 23-25 May 2016. http://www.agroforestry.eu/conferences/III_EURAFConference. Accessed 27 Mar 2017

Mosquera-Losada MR, Santiago-Freijanes JJ, Lawson G, Balaguer F, Vaets N, Burgess P, Rigueiro Rodríguez A (2016b) Agroforestry as a tool to mitigate and adapt to climate under LULUCF accounting. 3rd European Agroforestry Conference, Montpellier, 23–25 May 2016. http://www.agroforestry.eu/conferences/III_EURAFConference. Accessed 27 Mar 2017

Mosquera-Losada MR, Santiago Freijanes JJ, Pisanelli A, Rois M, Smith J, den Herder M, Moreno G, Malignier N, Mirazo JR, Lamersdorf N, Ferreiro Domínguez N, Balaguer F, Pantera A, Rigueiro-Rodríguez A, Gonzalez-Hernández P, Fernández-Lorenzo JL, Romero-Franco R, Chalmin A, Garcia de Jalon S, Garnett K, Graves A, Burgess PJ (2016c) Extent and success of current policy measures to promote agroforestry across Europe. Deliverable 8.23 for EU FP7 Research Project: AGFORWARD 613520. https://www.agforward.eu/index.php/en/extent-and-success-of-current-policy-measures-to-promote-agroforestry-across-europe.html. Accessed 24 Jan 2018

Mosquera-Losada MR, Santiago Freijanes JJ, Pisanelli A, Rois M, Smith J, den Herder M, Moreno G, Lamersdorf N, Ferreiro Domínguez N, Balaguer F, Pantera A, Papanastasis V, Rigueiro-Rodríguez A, Aldrey JA, Gonzalez-Hernández P, Fernández-Lorenzo JL, Romero-Franco R, Lampkin N, Burgess PJ (2017) How can policy support the uptake of agroforestry in Europe? Deliverable 8.24 for EU FP& Research Project: AGFORWARD. http://www.agforward.eu/index.php/es/how-can-policy-support-the-uptake-of-agroforestry-in-europe.html. Accessed 24 Jan 2018

Rigueiro-Rodríguez A, McAdam J, Mosquera-Losada MR (2009) Agroforestry in Europe. Advances in agroforestry. Kluwer, The Netherlands

Santiago-Freijanes JJ, Rigueiro-Rodríguez A, Aldrey JA, Moreno G, den Herder M, Burgess PJ, Mosquera-Losada MR (2018) Understanding agroforestry practices in Europe through landscape features policy promotion. Agrofor Syst. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10457-018-0212-z

Sciences Vie (2015) Rendements ceréalliers. L´idée de cultivar le blé à l´ombre est dejá à létude. Science and vie 76–77

USDA (2017) Agroforestry definition. https://www.usda.gov/topics/forestry/agroforestry. Accessed 27 Aug 2017

Acknowledgements

This work was funded through the AGFORWARD (www.agforward.eu) Project from the European Union Seventh Framework Programme for Research, Technological Development, and Demonstration under Grant Agreement No. 613520 and the Xunta de Galicia, Consellería de Cultura, Educación, e Ordenación Universitaria (“Programa de axudas á etapa posdoutoral DOG no. 122, 29/06/2016 p. 27443, exp: ED481B 2016/071-0”). The views and opinions expressed in this article are purely those of the writers and may not in any circumstances be regarded as stating an official position of the European Commission.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mosquera-Losada, M.R., Santiago-Freijanes, J.J., Pisanelli, A. et al. Agroforestry in the European common agricultural policy. Agroforest Syst 92, 1117–1127 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10457-018-0251-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10457-018-0251-5