Abstract

Stents are deployed to physically reopen stenotic regions of arteries and to restore blood flow. However, inflammation and localized stent thrombosis remain a risk for all current commercial stent designs. Computational fluid dynamics results predict that nonstreamlined stent struts deployed at the arterial surface in contact with flowing blood, regardless of the strut height, promote the creation of proximal and distal flow conditions that are characterized by flow recirculation, low flow (shear) rates, and prolonged particle residence time. Furthermore, low shear rates yield an environment less conducive for endothelialization, while local flow recirculation zones can serve as micro-reaction chambers where procoagulant and pro-inflammatory elements from the blood and vessel wall accumulate. By merging aerodynamic theory with local hemodynamic conditions we propose a streamlined stent strut design that promotes the development of a local flow field free of recirculation zones, which is predicted to inhibit thrombosis and is more conducive for endothelialization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The presence of atherosclerotic lesions in medium-sized vessels such as the coronary and carotid arteries can lead to inadequate perfusion of the heart and brain, respectively. Following approval by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1994, the standard of care for occlusive heart disease has been the implantation of stents, slender metal or plastic cylindrical mesh tubes, into the lumen of the affected vessel with the majority of cases targeting the coronary arteries. However, restenosis, the formation of a neointima that re-narrows the arterial lumen, is a recurrent problem in 30–40% of patients receiving bare metal stents (BMS).35 In vitro, in vivo, and computational studies have been performed to better understand how stent characteristics can affect restenosis. Clinical studies have noted a proportional relationship between strut thickness and angiographic restenosis.20,31 In addition, changing the arrangement of strut-strut intersections while keeping the total mass and surface area constant have yielded lower levels of vascular injury, thrombosis, and neointimal hyperplasia.35 Furthermore, patients implanted with rougher surface stents had lower rates of angiographic restenosis demonstrating the importance of stent surface properties.11 Other stent characteristics studied include the effective number of struts per cross-section, interstrut spacing, postdeployment strut orientation, strut amplitude, and strut radius of curvature.4,16,19,20,26 Computational and in vivo studies have shown that stent characteristics can alter coronary hemodynamics resulting in low wall shear stresses and intimal thickening in the vicinity of stent struts.5,24,25,37,38,48 All BMS struts induce at least some neointima hyperplasia which results in the burial of the struts and their effective removal from the vessel surface within weeks to months after implantation. Consequently for BMS, stent geometry in relation to local hemodynamics is particularly relevant during this early period.

In 2003 the FDA approved the clinical use of drug-eluting stents (DES) that release anti-proliferative drugs to successfully address the problem of restenosis. Their introduction resulted in a majority of patients receiving DES implantations until an FDA warning suggested a significant association between DES recipients and late-stent thrombosis (LST). Post-mortem studies showed strong correlations between LST and lack of endothelial coverage.12 In vitro studies by Simon et al. 40 demonstrated that endothelialization of the strut surface was inversely proportional to the thickness of the stent and areas devoid of cells were largest on the downstream side, which is the side with the largest flow separation zone. For DES, unlike BMS, the elution of the drug inhibits the formation of neointima. Consequently, the struts remain at the surface longer, protrude into the lumen extensively, and alter the hemodynamic environment for an extended period of time and perhaps indefinitely.

When a stent is deployed, the shape of the individual struts promotes blood flow separation creating proximal and distal recirculation zones. Slower moving flow in a recirculation zone yields lower shear stress values when compared to areas where the flow has not separated. These low shear stress levels correspond to atheroprone and procoagulant flow conditions and promote an environment that can retard endothelialization.41 In the absence of an endothelium, as is often the case when a stent is deployed, the highly thrombogenic extracellular matrix is exposed and can activate the coagulation cascade. In the presence of an intact endothelium, the secretion rate of tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), a thrombolytic agent, by endothelial cells is proportional to the local flow rate resulting in lower levels in recirculation zones.10 Conversely, secretion rates of coagulation factor von Willebrand Factor (vWF) increase in a low flow rate environment, further exacerbating a slowly moving procoagulant milieu.44 The synthesis of two potent inhibitors of platelet aggregation, nitric oxide (NO) and endothelial prostacyclin (PGI2), is proportional to the shear stress magnitude of the local flow field,13,17,30,42 and consequently lower synthesis rates in the recirculation zone contribute to the procoagulant environment. Recirculation zones can also disrupt the convective transport of nutrients, waste, and oxygen by entrapment. Entrapment of molecules, such as coagulation factors, and cells, including monocytes, can occur inside the vortex leading to longer residence times, prolonging the monocyte-to-endothelial cell interaction,6 and, when local anticoagulation factors are diminished by poor re-endothelialization, promoting coagulation.

Similarities exist between flow disturbances in the arterial tree due to the local natural geometry and those that arise due to the implantation of an endovascular stent. Flow separation from the arterial wall occurs at curves and branches where the flow cannot precisely follow the local geometries. Similarly, stent struts can promote blood flow separation creating proximal and distal recirculation zones that can entrap blood-borne coagulation agents, promote thrombogenesis and establish atheroprone flow conditions. Here we show that flow separation zones can be reduced in size or eliminated by the incorporation of aerodynamic theory into stent strut design and suggest that strut streamlining will prevent blood flow conditions that are conducive toward local inflammation and coagulation associated with BMS (early period) and DES (early and late periods) after deployment.

Methods

A set of steady and unsteady numerical simulations was conducted to elucidate the role of stent strut geometries and their effects on the local hemodynamic conditions in a generic section of a coronary artery (Fig. 1). Rather than investigating the flow field about specific commercial stent strut geometries, which are predominantly rectangular with slightly rounded corners and nonstreamlined (Table 1), we investigated representative geometries of commercial stents along with aerodynamically inspired designs. Steady simulations were conducted for six different stent strut geometries and the surrounding flow fields were analyzed in order to establish a relationship between the strut geometry and resulting flow characteristics (Fig. 2). Furthermore, the flow field about two representative cases, 4:1 circular arc and rectangular stent strut, were studied under unsteady conditions to understand the effects of pulsatility about two representative geometries. The continuity and momentum equations were solved using the Fluent Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) software (Ansys Inc., Lebanon, New Hampshire, USA). Pressure fields, shear stress and shear rate distributions are presented for each case studied.

Fluid Domain and Conditions

The geometrical model used for the steady simulations consists of a 19.2 mm long, L, and 3 mm in diameter, D, straight rigid tube (Fig. 1), while the geometrical model for the unsteady case was 8.2 mm long and 3 mm in diameter. The effects of elasticity in the vessel are small so the assumption of rigid tube flow is reasonable.21 In the steady model, a series of six independent rings with no connecting struts represents the architecture of the simplified stent (commercial stents are interconnected). The number of rings coincides with commercial stents used for shorter lesions, but higher numbers of rings are present in stents used to treat longer lesions. The unsteady model was comprised of a single strut (ring). The flow is assumed to be axisymmetric to minimize the computational cost; therefore the results are characteristic for any streamwise plane. This case ignores secondary motions that can arise in complex geometric environments of the cardiovascular system.

The cross-sectional geometry of the struts consists of rectangles and circular arcs with varying aspect ratios, AR, of width to height, w:h, equal to 2:1, 4:1, and 8:1 (Fig. 2). The width, w was kept constant at 200 μm for all cases while h was decreased from 100 μm to 50 μm to 25 μm for the 2:1, 4:1, and 8:1 aspect ratio cases, respectively. The interstrut spacing was set to 10w, which is in the interstrut distance range for typical commercial stents. Also, the first and last strut were located more than 20w streamwise into the flow field to ensure that any numerical error perturbation present at the inlet or outlet did not affect the local flow field.

The inlet boundary condition for the steady simulations consisted of a parabolic velocity profile with a mean velocity, \(\overline{U}\), equal to 0.38 m/s,3 which corresponds to the peak diastolic coronary blood flow velocity. The parabolic velocity profile is described by the following equation,

where \(\overline{U}\) is the mean velocity and r is the radial spatial coordinate. Similarly, for the unsteady simulations a pulsatile parabolic velocity inlet boundary condition with a range in \(\overline{U}\) between 0.082 and 0.38 m/s is defined by

At the exit boundary, a constant value was specified for the pressure, and a zero normal derivative was specified for the velocity. The no-slip condition was applied to all solid surfaces and a symmetry condition was applied to the centerline of the vessel. The dynamic viscosity, μ, and density, ρ, of the blood used for the numerical simulations were 0.00304 kg/m s2 and 1060 kg/m3,8 respectively. Coronary arteries are characterized by high blood flow rates and medium-size lumen diameters yielding relatively high shear stresses that inhibit the aggregation of blood components, which is a common phenomenon at lower shear rates. This characteristic of coronary arterial flow makes modeling blood as a Newtonian fluid an adequate approximation,15 since non-Newtonian effects are observed predominantly in much smaller vessels than the coronary arteries where cell–cell interactions are not negligible and the length scale of the cells is of the order of the vessel diameter. The assumption of Newtonian fluid can affect the computed dimensions of recirculation zones, which are populated by slower moving cells.7 The flow conditions for the steady simulations are limited to a single time point within the unsteady cardiac cycle, which coincides with the maximum flow rate during diastole and yields a Reynolds number based upon the vessel diameter, \(Re_D = \rho \overline{U} D/\mu\), of approximately 400, which is the peak Reynolds number for the cardiac cycle, while Re D for the unsteady simulations fluctuates between 86 and 400. Due to the unsteady nature of cardiac blood flow, the steady simulations provide quantitative results for the maximum flow rate instance and a qualitative representation of the rest of the cycle.

Governing Equations

The governing continuity and momentum equations for an unsteady, Newtonian, incompressible, viscous, axisymmetric flow in cylindrical coordinates are given by Eqs. (3)–(5),

where u and v are the axial and radial velocity components, respectively, and t is the time variable. The independent variables x and r are the streamwise and radial spatial coordinates, respectively. The pressure is denoted by p. The leftmost terms (∂/∂t) in Eqs. (4) and (5) are only relevant for the unsteady simulations. The flow field about the six different strut geometries shown in Fig. 2 were solved using a steady solver and compose the main thrust of the work.

The wall shear stress is defined by the following,

where \(\dot{\gamma}\) is the shear strain rate. The separation and reattachment points were determined from the point along the wall where the velocity gradient in the direction normal to the wall equaled zero.

Computational Fluid Dynamics

The governing equations were solved for each flow field using second-order finite difference solvers. A mesh convergence study was conducted by increasing the number of nodes approximately by a factor of 2 in each dimension. The approximate total number of nodes for the three different steady flow meshes were 81,000, 323,000, and 1,320,000. The mesh for the rectangular strut flow fields was composed of quadrilateral elements, while that for the circular arc strut flow fields was composed of quadrilateral and triangular elements. The total number of nodes surrounding the struts increased by approximately 3.88 and 3.99 times from mesh 1 to mesh 2 and from mesh 2 to mesh 3, respectively. The meshes were generated manually with a higher concentration of nodes near the wall and stent struts to resolve the larger near-wall gradients (Fig. 3). Figure 4 shows a typical grid convergence plot for wall shear stress per unit length (\(\hat{\tau}_w\)) variation over a strut as a function of grid spacing. Each iteration was run until the solution converged. The convergence criterion was reached when the residuals of the independent variables had decreased by at least 14 orders of magnitude. Furthermore, the set of iterations showed that the converged solutions were grid independent. Refining the grid spacing further would only decrease the error by less than 3% as shown by the theoretical \(\hat{\tau}_w\) value calculated using Richardson extrapolation.34 The mesh density for the unsteady simulations corresponds to a combination between the finest and second finest grid around a single strut in a shortened vessel.

Results

An axisymmetric plane of the fluid flow domain shown in Fig. 1 was studied using CFD to better understand the effects of six streamlined and nonstreamlined stent strut geometries with varying aspect ratios, AR, in a blood vessel (Fig. 2). The coordinates on the plots shown in this section have been modified for ease of presentation without any modifications to the data. Axes corresponding to distance have been nondimensionalized by w and the location of the leading edge of the third strut has been redefined as x/w = 0. Although the steady simulation flow field was solved about six different neighboring struts, the data presented focuses only on a representative case, the third strut. The flow field about each strut was similar with equal separation/reattachment distances and a 3% average variation in the wall shear stress, which has no physiological implications. These variations can become important for longer stents than the one studied here, since the flow is loosing momentum as it travels downstream. The effect is greater for thicker than thinner or streamlined struts.

Pressure Field

Figure 5 shows the nondimensionalized pressure field in the vicinity of the struts with streamlines in the foreground. The pressure was nondimensionalized by dividing the static pressure by the dynamic pressure, \(p^* = p/\frac{1}{2}\rho \overline{U}^2\). A higher pressure region is present for each case on the upstream side of the strut. The pressure gradient weakens as the height, h, decreases. The flow fields along the top surfaces of the struts experience a pressure decrease as x/w increases, but upstream of the struts the pressure increases as it approaches x/w = 0. The upstream influence of the strut increases as the height of the strut increases. Since the flow field shown in Fig. 5 is laminar and steady, the superimposed streamlines correspond to the path a fluid element traveled in space. A significant recirculation region, as denoted by the streamlines, is present both upstream and downstream of the 2:1 rectangular geometry (Fig. 5a). Similar results are observed on the upstream and downstream side of the 4:1 and 8:1 rectangular struts (Figs. 5b and 5c). For the circular arc stent strut geometries, flow separation is only observed in the vicinity of the 2:1 aspect ratio (Fig. 5d). The 4:1 and 8:1 aspect ratio circular arc struts do not demonstrate any flow separation for the flow conditions studied.

Separation Zone Cross-Sectional Area

Table 2 shows the upstream and downstream separation areas normalized by the upstream and downstream separation areas of the rectangular 8:1 aspect ratio strut, correspondingly. The upstream separation zones corresponding to the rectangular 4:1 and 2:1 cases, increased 3.8 and 8.4 times, respectively, when compared to that of the 8:1 aspect ratio strut. Correspondingly, the upstream separation zone for the 2:1 circular arc increased 20%. The downstream separation area increased nonlinearly from 5.7 to 42.2 times for the 4:1 and 2:1 rectangular struts, respectively. The downstream separation zone for the 2:1 circular arc increased about 14.4 times with respect to the downstream separation zone of the rectangular 8:1 aspect ratio strut, which is a significantly larger increase than the increase observed for the upstream side, but significantly lower than that observed for the 2:1 rectangular strut. The upstream separation zone for the rectangular 4:1 case is larger than that for the 2:1 circular arc strut, but the opposite is true for the downstream side. Although sharing a similar aspect ratio, the upstream and downstream separation areas of the 2:1 circular arc are reduced by 98% and 66%, respectively when compared with the 2:1 rectangular stent strut.

Separation Distance

Table 3 shows the separation distance corresponding to the axial length of the separation zone. The separation distance increased as h increased. The upstream separation distances are 0.223w, 0.145w, and 0.074w for the 2:1, 4:1, and 8:1 rectangular stent strut geometries, respectively. The downstream separation length for the 2:1 rectangular stent strut extends 0.845w. The downstream separation length for the 4:1 and 8:1 rectangular struts are 0.257w and 0.094w, respectively. To contrast the rectangular and circular arc geometries, Table 3 also shows the upstream and downstream separation lengths for a cross-sectional 2:1 circular arc strut, which extended 0.080w and 0.469w, respectively. Thus, the downstream separation distance for the 2:1 AR is decreased by approximately 44% when the geometry is simply changed from a rectangular to a circular arc cross-section while keeping the same aspect ratio.

Wall Shear Stress and Shear Rate

Wall shear stress, τ w , and shear rate, \(\dot{\gamma}\), distributions over the rectangular struts and in the near vicinity are shown in Fig. 6a as a function of x/w. Due to the proportional relationship between wall shear stress and shear rate, \(\tau_w = \mu \dot{\gamma}\), the following discussion although focused on the wall shear stress distributions is applicable to the shear rate distributions. As x/w → 0− and x/w → 1+, τ w → 0 for all rectangular cases in Fig. 6a. The effective region over which τ w ≈ 0 decreases as h decreases and is always confined immediately upstream or downstream of the strut. The effects are more noticeable in the downstream side. Figure 6b shows the wall shear stress distribution over and in the near vicinity of the circular arc strut geometries. The wall shear stress levels for the 2:1 circular arc follow the trends observed for the rectangular designs; low shear stress levels dominate the vicinity of the struts, but without distinct peaks in the shear stress distribution (Fig. 6). The regions of low shear stress coincide with the separation zones that in the case of the 4:1 and 8:1 circular arc designs are negligible. The shear stress distribution for the rectangular designs has two peaks at the upstream and downstream corners where the flow velocity increases significantly over a small distance. Removing the abrupt change in geometry encountered in a rectangular strut and replacing it with gradual geometric changes, such as those observed in the circular arcs, inhibits the development of regions of concentrated high shear stress. The wall shear stress values for the upstream peaks corresponding to the rectangular stent geometries increased 54 and 101% when h was doubled and quadrupled from 25 to 50 μm and 25 to 100 μm, respectively (Table 4). The increase in τ w for the downstream peaks was less with a 27 and 32% increase when AR was varied from 8:1 to 4:1 and 4:1 to 2:1, respectively. Due to the eventual favorable pressure gradient over the forward face of the circular arc struts, the flow accelerated and resulted in a gradual increase of the shear stress values. The maximum shear stress over the circular arc struts increased by 53 and 68% when AR was varied from 8:1 to 4:1 and 4:1 to 2:1, respectively. The maximum shear stress values corresponding to the circular arcs were approximately 50% lower than the corresponding rectangular geometries (Fig. 6).

Streamlined Geometries

For the Reynolds number and flow conditions studied we define a streamlined geometry as one that inhibits flow separation due to gradual changes in the slope over the surface. While substantial reduction of flow separation is accomplished with a 2:1 circular arc geometry, the flow about the circular arc struts of AR values 4:1 and 8:1 does not separate (Figs. 5d–5f) and exhibits gradual variations in the shear rate and shear stress distributions (Fig. 6b). The 4:1 and 8:1 circular arc stent strut geometries meet the streamlined body definition (Figs. 5e–5f).

Effects of Pulsatility on Stent Strut Geometries

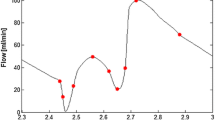

In contrast to the constant separation/reattachment distances observed in Fig. 5 for steady flow, Fig. 7 demonstrates the fluctuational behavior of the separation and reattachment distances during one pulsatile time period in the recirculation zones upstream and downstream of an AR = 4:1 nonstreamlined stent strut. Under unsteady flow, the upstream and downstream separation/reattachment distances for the rectangular strut varied inversely proportional and proportional, respectively, to the instantaneous Reynolds number, which fluctuates from about 86 to 400 (Fig. 7b). The upstream separation (S ux ) and downstream reattachment (S dx ) distances along the vessel wall fluctuated 0.028w and 0.054w, respectively, throughout the nondimensional pulsatile time period, \(t/\hat{t}\), where \(\hat{t}\) is the total length of time of the pulsatile period. The upstream reattachment (S uy ) and downstream separation (S dy ) distances on the side surfaces of the strut fluctuated by 0.021w and 0.015w, correspondingly. In contrast, the flow did not separate at any time point for a corresponding 4:1 streamlined strut under pulsatile flow conditions.

Effects of pulsatility on fluctuational behavior. (a) Schematic of nondimensional separation and reattachment distances along the upstream vessel wall (S ux ), upstream strut side surface (S uy ), downstream strut side surface (S dy ), and downstream vessel wall (S dx ), of a rectangular stent strut. (b) Nondimensional separation and reattachment distances S ux , —●—; S uy , \(\cdot \cdot \cdot\); S dy , —; S dx , - - -; for a rectangular stent strut of AR = 4:1 for one pulsatile time period

Discussion

Small but significant numbers of morbidities and mortalities are associated with coronary artery stents43 of which more than 500,000 are implanted per year in the USA alone.46 Of many factors influencing clinical outcomes, stent design has been directed mainly to material strength and biocompatibility, strut flexibility, surface properties, strut thickness, strut layout, drug coatings (of DES), and improved deployment with prevention of malapposition. We extend this list to include the important influence of strut geometry upon the local hemodynamics. The geometry-hemodynamics relationship also greatly influences local shear forces and transport properties intimately related to most of the above considerations.

Steady and unsteady numerical simulations performed at Reynolds numbers in the physiological range of coronary arteries demonstrate that the stent strut geometry can alter the local blood flow resulting in characteristics of flow fields that have been previously associated with atherosusceptible endothelial cell phenotypes and procoagulant conditions.32 The flow field upstream and downstream of the nonstreamlined strut cross-sections is governed by recirculating flow. Such flow structure is one of the characteristics observed in atherosusceptible regions of the arterial tree. Regions in the arterial tree where the flow has to turn sharply promote fluid flow separation away from the wall resulting in the development of vortices, secondary motions, and flow reversal. This occurs in regions like the carotid sinus where rapid expansion of the arterial geometry promotes flow separation. In this region, the flow cannot accurately follow the vessel geometry resulting in a regional separation of flow with the development of secondary motions, such as helical motions accompanied by flow reversal.22 This specific region correlates with intimal thickening and the presence of plaque. Conversely, the carotid flow-divider, an area where the flow is predominantly unidirectional and attached to the wall, is relatively spared of intimal thickening.51 Other regions where the flow separates due to the arterial geometry include the inner wall of the aortic arch, which exhibits high endothelial expression of ICAM-1 and VCAM-145 and atherosusceptible and procoagulant phenotypes,32 and the proximal renal ostium, which exhibits greater propensity toward the development of lesions as opposed to the distal side of the renal ostium where flow separation is unlikely to occur.9,29,49,50 Similarly after stent implantation, the newly formed wall composed of the blood vessel and struts creates a boundary with a sudden change in direction when transitioning from the top to the side surface of the strut where the blood flow can separate when trying to change directions rapidly.

As blood cells travel tangentially to the strut surface they are exposed to large shearing forces (Fig. 6). In the case of platelets, high shear forces result in activation and release of thromboxane A2 (TXA2) and adenosine diphosphate (ADP), two potent mediators of platelet aggregation. Our numerical steady simulations of rectangular stent struts show shear rate values above 3000 s−1. Platelet activation can occur at shear rate levels as low as 2200 s−1.39 Furthermore, erythrocytes release about 2% of their ADP at shear rate values of 5680 s−1, resulting in sufficient amounts of ADP to induce platelet aggregation.1 ADP induces shape change in platelets, and promotes platelet aggregation and surface expression of fibrin receptors. Activated platelets or erythrocytes exposed to high shear forces while being convected along the strut surface have the potential to enter the recirculation zone. The recirculation zone is likely populated by lower amounts of PGI2 and NO, potent inhibitors of platelet aggregation. Under normal conditions the interaction between PGI2 and TXA2 represents a balanced system that controls platelet function by inhibiting platelet aggregation in the absence of local injury.23 However, current commercial (nonstreamlined) stent struts can establish flow conditions that lead to an unbalanced state favoring platelet aggregation and thrombogenesis (Table 1). If thrombogenesis occurs, shed procoagulant microparticles33 can become entrapped in the recirculation zone further accelerating the thrombus growth rate. Figures 8a and 8b summarize the hemostatic balance in arteries and outline the predicted procoagulant consequences of stent-related flow separation.

Blood contains multiple procoagulant proteins as well as natural anticoagulants that together with the endothelium normally maintain a non-coagulation state. (a) In the normal artery wall the secreted and surface-presented anticoagulant molecules of the endothelium help maintain hemostatic balance. ADP, adenosine diphosphate; TF, tissue factor; vWF, von Willebrand factor; PGI2, prostacyclin; NO, nitric oxide; TFPI, tissue factor pathway inhibitor; tPA, tissue plasminogen activator; TM, thrombomodulin. (b) The deployment of current commercial (nonstreamlined) stents promotes flow separation in the proximal and distal regions of the strut. Procoagulant conditions are greatly increased around the stent strut by the following: (i) accelerated flow over the strut edges yields shear stress magnitudes that can activate platelets some of which will enter the distal flow separation zone, (ii) recirculation zones retain activated platelets and procoagulant factors that can reach critical concentrations for activation of the coagulation cascade, (iii) the removal of endothelium during angioplasty and stenting eliminates anticoagulant mechanisms and exposes the highly thrombogenic extracellular matrix surface. Furthermore, (iv) low flow velocity (shear stress) inhibits endothelialization of the vessel and strut surface. (c) A streamlined stent strut inhibits fluid flow separation and high shear stress peaks that can activate platelets. Furthermore, a streamlined geometry will be less likely to generate recirculation zones therefore decreasing the residence time of procoagulant molecules and the probability of thrombogenesis despite the absence of endothelium. Undisturbed flow proximal and distal to the streamlined strut favors endothelialization of the vessel and strut surface. (d) An endothelialized vessel and strut surface provide an anticoagulant environment that helps maintain hemostatic balance and protect against stent-related thrombosis

The ideal surface to inhibit thrombogenesis consists of an intact endothelium in an atheroprotective flow environment. Endothelial cells normally express an anticoagulant phenotype. When a stent is implanted, there is a high probability of partial endothelial denudation36 that tips the balance toward a procoagulant surface environment. A high flow (high shear) rate environment has been identified as a superior condition for endothelialization when compared to a low flow (low shear) rate environment41 (although very high shear stresses in excess of 38 Pa inhibit endothelial cell attachment). Furthermore, the strut leading and trailing edge angles influence endothelialization rates; smaller slopes being more favorable for endothelialization.18 Depending on the geometric characteristics of the stent strut cross-section, the local flow environment can promote, retard, or inhibit endothelialization.18,41 A nonstreamlined strut cross-section will promote flow separation and promote development of recirculation zones yielding low shear rates (Fig. 8b). In contrast, Figs. 8c and 8d illustrate how a streamlined strut geometry will minimize or avoid the generation of a low flow velocity environment distal and proximal to the strut and will promote faster endothelialization of the strut surface and the neighboring vessel wall.

Shear stress levels over the surface of a nonstreamlined or thick strut can reach very high levels that can also be detrimental to endothelialization. It has been shown that the yield stress corresponding to endothelial denudation is about 38 Pa,14 which is about 13 times typical coronary arterial values, but plausible in stenotic regions or over the top surface of stent struts that are exposed to much higher blood flow velocities than those present in the near-wall region (Fig. 6). In contrast, appropriately designed streamlined struts will avoid the development of low shear stress sites in the near vicinity as well as local high shear stress peaks that can inhibit endothelialization.

Nonstreamlined stent struts such as rectangular cross-section geometries can be modified by decreasing the height, h, and consequently lessening the effect of h on the flow field. However, the recirculation zone persists maintaining the potential to form a nidus for thrombi (Figs. 5a–5c). The decrease in thickness not only decreases the size of the recirculation volume, but also decreases the area of the endothelium exposed to disturbed flow thus increasing the probability of endothelialization of adjacent tissue. The peak shear stresses and the shear stress values over the strut surface decline with decreasing thickness of the rectangular strut (Fig. 6a). The lower shear stress values observed for the 4:1 and 8:1 AR rectangular cross-section struts are more conducive toward endothelialization of the strut surface despite the retention of a recirculation zone (Figs. 5a–5c). These considerations likely contribute to the improved outcome for thinner stent struts observed clinically.20,31

The numerical simulation results presented here are supported by clinical results from the ISAR-STEREO Trial.20 In the ISAR-STEREO Trial, patients were randomly implanted with two types of bare metal stents with very similar architectures, material properties, and strut widths (100 μm), but with different strut thicknesses (50 vs. 140 μm). The angiographic restenosis rates decreased by 42% in the group of patients that received the 50 μm vs. the thicker (140 μm) strut group. Given that the only major variable that was changed in the clinical trial was the strut thickness, it can be concluded that the stent strut geometry affects the restenosis rate, which is a marker of clinical success. As strut thickness increases for a nonstreamlined geometry the flow disturbances increase nonlinearly, generating flow conditions that have been linked to an atherosusceptible flow environment in which there are low levels of NO and PGI2, molecules linked to inhibition of smooth muscle cell (SMC) proliferation and migration27,47 in addition to their anti-coagulant properties. SMCs and their secreted extracellular matrix are the predominant elements of neointimal hyperplasia, which is principally responsible for vessel restenosis after stent implantation. As the thickness of a nonstreamlined stent strut decreases, the tissue area that will experience flow recirculation will decrease resulting in a lower probability of restenosis, a scenario consistent with the results of the ISAR-STEREO Trial. Furthermore, studies by Mattson et al. 28 have shown that increasing the flow rate (shear stress) regressed restenosis.

For a nonstreamlined stent strut design, improvement can be made by a decrease in h to minimize, though not eliminate, the recirculation volume. However, when the hemodynamics of the local environment is taken into account in combination with aerodynamic theory, a streamlined stent cross-section can be incorporated into a stent. A streamlined design can minimize or eliminate flow recirculation zones, establishing an atheroprotective and anticoagulant flow environment conducive to endothelialization of the strut surface and adjacent vessel wall, optimal conditions for clinical success (Fig. 8). As observed in the steady and unsteady simulations, a large decrease in flow separation results from a modest degree of streamlining. Thus changes in the geometry of relatively thick struts should lead to improved hemodynamics, an attractive compensation as the material strength limits of strut thinness are reached. In the case of BMS, streamlining will improve the hemodynamics during the critical period of several weeks before the stent is overgrown by neointima. In the case of DES, the struts remain on the artery surface and protrude into the flow for long periods of time due to their antiproliferative therapeutic properties that prevent neointimal overgrowth. A nonstreamlined DES strut protruding into the flow field promotes the creation of recirculation zones, which are nidi for thrombogenesis, and high shear stress peaks over the surface can activate platelets. A streamlined DES will be less likely to create the conditions necessary for the development of recirculation zones and high shear stress peaks over the surface, even at higher strut thicknesses than a thinner nonstreamlined strut, resulting in faster healing of the vessel and less probability of stent thrombosis.

References

Alkhamis, T. M., R. L. Beissinger, J. R. Chediak. Red blood cell effect on platelet adhesion and aggregation in low-stress shear flow. Myth or fact? ASAIO Trans. 34:868-873, 1988.

Astrand, P., K. Rodahl, H. A. Dahl, S. B. Stromme. Textbook of Work Physiology: Physiological Bases of Exercise. Champaign: Human Kinetics, 2003.

Auriti, A., C. Cianfrocca, C. Pristipino, S. Greco, M. Galeazzi, V. Guido, M. Santini. Improving feasibility of posterior descending coronary artery flow recording by transthoracic Doppler echocardiography. Eur. J. Echocardiogr. 4:214–220, 2003.

Berry, J. L., A. Santamarina, J. E. Moore, S. Roychowdhury, W. D. Routh. Experimental and computational flow evaluation of coronary stents. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 28:386–398, 2000.

Chen, M. C., P. C. Lu, J. S. Chen, N. H. Hwang. Computational hemodynamics of an implanted coronary stent based on three-dimensional cine angiography reconstruction. ASAIO J. 51:313–320, 2005.

Chiu J., C. Chen, P. Lee, C. Yang, H. Chuang, S. Chien, S. Usami. Analysis of the effect of disturbed flow on monocytic adhesion to endothelial cells. J. Biomech. 36:1883–1895, 2003.

Choi, H. W., A. I. Barakat. Numerical study of the impact of non-Newtonian blood behavior on flow over a two-dimensional backward facing step. Biorheology. 42:493-50, 2005.

Cutnell, J., K. Johnson. Physics, New York: Wiley, 1998.

DeBakey, M. E., G. C. Morris, R. O. Morgen, E. S. Crawford, D. A. Cooley. Lesions of the renal artery. surgical technic and results. Am. J. Surg. 107:84-96, 1964.

Diamond, S. L., S. G. Eskin, L. V. McIntire. Fluid flow stimulates tissue plasminogen activator secretion by cultured human endothelial cells. Science. 243:1483-1485, 1989.

Dibra, A., A. Kastrati, J. Mehilli, J. Pache, R. von Oepen, J. Dirschinger, A. Schömig. Influence of stent surface topography on the outcomes of patients undergoing coronary stenting: a randomized double-blind controlled trial. Catheter Cardiovasc. Interv. 65:374-380, 2005.

Finn, A. V., M. Joner, G. Nakazawa, F. Kolodgie, J. Newell, M. C. John, H. K. Gold, R. Virmani. Pathological correlates of late drug-eluting stent thrombosis: strut coverage as a marker of endothelialization. Circulation. 115:2435–2441, 2007.

Frangos, J. A., S. G. Eskin, L. V. McIntire, C. L. Ives. Flow effects on prostacyclin production by cultured human endothelial cells. Science. 227:1477-1479, 1985.

Fry, D. L. Acute vascular endothelial changes associated with increased blood velocity gradients Circ. Res. 22:165-197, 1968.

Fung, Y. C. Biomechanics: Mechanical Properties of Living Tissues. New York: Springer, 1993.

Garasic, J. M., E. R. Edelman, J. C. Squire, P. Seifert, M. S. Williams, C. Rogers. Stent and artery geometry determine intimal thickening independent of arterial injury. Circulation. 101:812-818, 2000.

Grabowski, E. F., E. A. Jaffe, B. B. Weksler. Prostacyclin production by cultured endothelial cell monolayers exposed to step increases in shear stress. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 105:36–43, 1985.

Hamuro, M., J. C. Palmaz, E. A. Sprague, C. Fuss, J. Luo. Influence of stent edge angle on endothelialization in an in vitro model. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 12:607-611, 2001.

He, Y., N. Duraiswamy, A. O. Frank, J. E. Moore. Blood flow in stented arteries: a parametric comparison of strut design patterns in three dimensions. J. Biomech. Eng. 127:637–647, 2005.

Kastrati, A., J. Mehilli, J. Dirschinger, F. Dotzer, H. Schühlen, F. J. Neumann, M. Fleckenstein, C. Pfafferott, M. Seyfarth, A. Schömig. Intracoronary stenting and angiographic results: strut thickness effect on restenosis outcome (ISAR-STEREO) trial. Circulation. 103:2816–2821, 2001.

Ku, D. N. Blood Flow in Arteries. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 29:399-434, 1997

Ku, D. N., D. P. Giddens. Pulsatile flow in a model carotid bifurcation. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 3:31-39, 1983.

Kumar, V., R. S. Cotran, S. L. Robbins. Basic Pathology. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders Company, 1997.

LaDisa, J. F., I. Guler, L. E. Olson, D. A. Hettrick, J. R. Kersten, D. C. Warltier, P. S. Pagel. Three-dimensional computational fluid dynamics modeling of alterations in coronary wall shear stress produced by stent implantation. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 31:972-980, 2003.

LaDisa, J. F., D. A. Hettrick, L. E. Olson, I. Guler, E. R. Gross, T. T. Kress, J. R. Kersten, D. C. Warltier, P. S. Pagel. Stent implantation alters coronary artery hemodynamics and wall shear stress during maximal vasodilation. J. Appl. Physiol. 93:1939–1946, 2002.

LaDisa, J. F., L. E. Olson, D. A. Hettrick, D. C. Warltier, J. R. Kersten, P. S. Pagel. Axial stent strut angle influences wall shear stress after stent implantation: analysis using 3D computational fluid dynamics models of stent foreshortening. Biomed. Eng. Online. 4:59, 2005.

Marks, D. S., J. A. Vita, J. D. Folts, J. F. Keaney, G. N. Welch, J. Loscalzo, Inhibition of neointimal proliferation in rabbits after vascular injury by a single treatment with a protein adduct of nitric oxide. J. Clin. Invest. 96:2630–2638, 1995.

Mattsson, E. J. R., T. R. Kohler, S. M. Vergel, A. W. Clowes, Increased blood flow induces regression of intimal hyperplasia. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 17:2245-2249, 1997.

Nguyen, N. D., A. K. Haque, Effect of hemodynamic factors on atherosclerosis in the abdominal aorta. Atherosclerosis. 84:33-39, 1990.

Noris, M., M. Morigi, R. Donadelli, S. Aiello, M. Foppolo, M. Todeschini, S. Orisio, G. Remuzzi, A. Remuzzi. Nitric oxide synthesis by cultured endothelial cells is modulated by flow conditions. Circ. Res. 76:536-543, 1995.

Pache, J., A. Kastrati, J. Mehilli, H. Schühlen, F. Dotzer, J. Hausleiter, M. Fleckenstein, F. J. Neumann, U. Sattelberger, C. Schmitt, M. Müller, J. Dirschinger, A. Schömig. Intracoronary stenting and angiographic results: strut thickness effect on restenosis outcome (ISAR-STEREO-2) trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 41:1289-1292, 2003.

Passerini, A. G., D. C. Polacek, C. Shi, N. M. Francesco, E. Manduchi, G. R. Grant, W. F. Pritchard, S. Powell, G. Y. Chang, C. J. Stoeckert, P. F. Davies. Coexisting proinflammatory and antioxidative endothelial transcription profiles in a disturbed flow region of the adult porcine aorta. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101:2482-2487, 2004.

Reininger, A. J., H. F. G. Heijnen, H. Schumann, H. M. Specht, W. Schramm, Z. M. Ruggeri, Mechanism of platelet adhesion to von Willebrand factor and microparticle formation under high shear stress. Blood. 107:3537-3545, 2006.

Roache, P. J. Verification and Validation in Computational Science and Engineering. Albuquerque: Hermosa Publishers, 1998.

Rogers, C., E. R. Edelman. Endovascular stent design dictates experimental restenosis and thrombosis. Circulation. 91:2995-3001, 1995.

Rogers, C., D. Y. Tseng, J. C. Squire, E. R. Edelman. Balloon-artery interactions during stent placement: a finite element analysis approach to pressure, compliance, and stent design as contributors to vascular injury. Circ. Res. 84:378-383, 1999.

Sanmartín, M., J. Goicolea, C. García, J. García, A. Crespo, J. Rodríguez, J. M. Goicolea. Influence of shear stress on in-stent restenosis: in vivo study using 3D reconstruction and computational fluid dynamics. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 59:20-27, 2006.

Seo, T., L. G. Schachter, A. I. Barakat. Computational study of fluid mechanical disturbance induced by endovascular stents. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 33:444-456, 2005.

Shankaran, H., P. Alexandridis, S. Neelamegham. Aspects of hydrodynamic shear regulating shear-induced platelet activation and self-association of von Willebrand factor in suspension. Blood. 101:2637-2645, 2003.

Simon, C., J. C. Palmaz, E. A. Sprague. Influence of topography on endothelialization of stents: clues for new designs. J. Long Term Eff. Med. Implants. 10:143-151, 2000.

Sprague, E. A., J. Luo, J. C. Palmaz. Human aortic endothelial cell migration onto stent surfaces under static and flow conditions. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 8:83-92, 1997.

Stamler, J., M. E. Mendelsohn, P. Amarante, D. Smick, N. Andon, P. F. Davies, J. P. Cooke, J. Loscalzo. N-acetylcysteine potentiates platelet inhibition by endothelium-derived relaxing factor. Circ. Res. 65:789-795, 1989.

Stone, G. W., J. W. Moses, S. G. Ellis, J. Schofer, K. D. Dawkins, M. C. Morice, A. Colombo, E. Schampaert, E. Grube, A. J. Kirtane, D. E. Cutlip, M. Fahy, S. J. Pocock, R. Mehran, M. B. Leon. Safety and efficacy of sirolimus- and paclitaxel-eluting coronary stents. N. Engl. J. Med. 356:998-1008, 2007.

Sun, R. J., S. Muller, X. Wang, F. Y. Zhuang, J. F. Stoltz. Regulation of von Willebrand factor of human endothelial cells exposed to laminar flows: an in vitro study. Clin. Hemorheol. Microcirc. 23:1-11, 2000.

Suo, J., D. E. Ferrara, D. Sorescu, R. E. Guldberg, W. R. Taylor, D. P. Giddens. Hemodynamic shear stresses in mouse aortas: implications for atherogenesis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 27:346-351, 2007.

Topol, E. J. Coronary–artery stents—Gauging, Gorging, and Gouging. N. Engl. J. Med. 339:1702–1704, 1998.

von der Leyen, H. E., G. H. Gibbons, R. Morishita, N. P. Lewis, L. Zhang, M. Nakajima, Y. Kaneda, J. P. Cooke, V. J. Dzau. In vivo gene transfer to prevent neointima hyperplasia after vascular injury: effect of overexpression of constitutive nitric oxide synthase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92:1137-1141, 1995.

Wentzel, J. J., R. Krams, J. C. Schuurbiers, J. A. Oomen, J. Kloet, W. J. van Der Giessen, P. W. Serruys, C. J. Slager. Relationship between neointimal thickness and shear stress after Wallstent implantation in human coronary arteries. Circulation. 103:1740-1745, 2001.

Yamamoto, T., Y. Ogasawara, A. Kimura, H. Tanaka, O. Hiramatsu, K. Tsujioka, M. J. Lever, K. H. Parker, C. J. H. Jones, C. G. Caro, F. Kajiya. Blood velocity profiles in the human renal artery by doppler ultrasound and their relationship to atherosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 16:172-177, 1996.

Yutani, C., M. Imakita, H. Ishibashi-Ueda, A. Yamamoto, S. Takaichi. Localization of lipids and cell population in atheromatous lesions in aorta and its main arterial branches in patients with hypercholesterolemia. In: Role of Blood Blow in Atherogenesis, edited by R. M. Nerem, S. Glagov, T. Yamaguchi, Y. Yoshida, C. G. Caro, Tokyo: Springer-Verlag, 1988, pp. 25–31.

Zarins, C. K., D. P. Giddens, B. K. Bharadavaj, V. S. Sottiurai, R. F. Mabon, S. Glagov. Carotid bifurcation atherosclerosis. quantitative correlation of plaque localization with flow velocity profiles and wall shear stress. Circ. Res. 53:502–514, 1983.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health under NIH grants HL62250, HL096059 and Training Grant T32 HL07954. We thank Drs. Scott L. Diamond, Melissa D. Sánchez, Jennifer E. Clark, Josué Sznitman, and David A. Boger for their constructive criticism.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jiménez, J.M., Davies, P.F. Hemodynamically Driven Stent Strut Design. Ann Biomed Eng 37, 1483–1494 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10439-009-9719-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10439-009-9719-9