Abstract

The aims of this study were to investigate patterns of home and community care (HACC) use and to identify factors influencing first HACC use among older Australian women. Our analysis included 11,133 participants from the Australian Longitudinal Study of Women’s Health (1921–1926 birth cohort) linked with HACC use and mortality data from 2001 to 2011. Patterns of HACC use were analysed using a k-median cluster approach. A multivariable competing risk analysis was used to estimate the risk of first HACC use. Approximately 54% of clients used a minimum volume and number of HACC services; 25% belonged to three complex care use clusters (referring to higher volume and number of services), while the remainder were intermediate users. The initiation of HACC use was significantly associated with (1) living in remote/inner/regional areas, (2) being widowed or divorced, (3) having difficulty in managing income, (4) not receiving Veterans’ Affairs benefits, (5) having chronic conditions, (6) reporting lower scores on the SF-36 health-related quality of life, and (7) poor/fair self-rated health. Our findings highlight the importance of providing a range of services to meet the diverse care needs of older women, especially in the community setting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The number of people aged 60 and over is projected to reach over 2 billion worldwide by 2050, which is more than double the 2015 figure (UNDESA 2015). Representing the most rapidly growing age group, individuals in their eighties are increasingly dependent on care from formal sources (Stones and Gullifer 2016). The transition from informal family-based support to institutional and community care services reflects the participation of more women in the labour market and their adoption of a nuclear family structure (Genet et al. 2011; Lowenstein et al. 2001). Adding to an already overburdened healthcare system, the need for formal care is anticipated to increase until the year 2050 (Wouterse et al. 2015). Debate exists on how to best provide long-term care for an ageing population and ways to address this complex policy issue (Francesca et al. 2011; Merlis 2000).

Over the past few decades, increased costs and consumer choices have led to a shift from long-term residential aged care to lower-cost home- and community-based care. Moreover, this trend is expected to continue into the foreseeable future (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2008a; Department of Work and Pensions 2007). For instance, older people in Europe, Australia, and the USA prefer to receive aged care in the home and community-based setting (Chen and Berkowitz 2012; EUROBAROMETER 2007; Productivity Commission 2011). Several countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) have been promoting ‘Age in Place’ policies in recent years (Francesca et al. 2011).

In contrast to many countries, Australia has a well-developed long-term care system (formally known as aged care) for older people aged 65 and over. Beginning in the 1980s, policy-makers have focused on providing aged care in the community setting. This was precipitated by the need to reduce the burgeoning cost of residential aged care and to address the desire of older Australians to remain in their own home (Jeon and Kendig 2017; Keleher 2003; Productivity Commission 2011).

The Commonwealth Home and Community Care (HACC) programme was implemented in 1985 to provide a range of care services for older Australians (including younger people with disabilities) in the community setting (Department of Health and Ageing 2008). Additionally, this programme is important for older Australians who may later require more advanced care (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2017; Palmer and Short 2000). Until 2012, HACC was funded by the Commonwealth of Australia and state/territory entities (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2014). Thereafter, the Australian Government assumed full responsibility for the financing and management of HACC (except for Victoria and West Australia). Around the same time, the legislature announced the Living Longer Living Better plan to reform aged care services in the community (Department of Health and Ageing 2012). Specifically, HACC and three smaller commonwealth programmes were merged into the Commonwealth Home Support Programme (CHSP) as a means to consolidate and increase the efficiency of aged care to older Australians.

HACC provides a range of services to allow older people to remain in their own home as long as possible, rather than entering residential aged care (RAC) (Department of Health and Ageing 2008; Jorm et al. 2010). Services include domestic assistance with meals and personal care, home maintenance and medication, transportation, social care, respite care, as well as nursing and allied health services (Department of Health and Ageing 2012). Approximately 20% of people aged 65 and over receive support from HACC, constituting the largest aged care programme in the country (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2015). From 2013 to 2014, more than 775,000 older Australians received HACC, with the majority being women (> 65%) (Department of Social Services (DSS) 2014).

Although HACC is a pivotal component of the community aged care system in Australia, limited evidence is available regarding client characteristics and their patterns of care needs (Jorm et al. 2010). Nine distinct groups of HACC clients were identified in a recent study, with most (~ 75%) only using a few of the wide range of available services (Kendig et al. 2012). Demographic vulnerability and health-related needs of older people were associated with the use of community age care (Lafortune et al. 2009). Women tend to use more aged care than men, as they typically live longer and manifest multiple morbidities and disabilities (Laditka and Laditka 2001). Furthermore, women have a greater likelihood to live alone in later life, increasing their dependence on formal aged care (McCann et al. 2012). Although nearly two-thirds of clients in the Australian aged care system are women, there is a paucity of information pertaining to their patterns of service use and factors influencing the risk of HACC use.

The aim of the present study was to identify the patterns and timing of HACC use among older women in Australia. Specifically, we addressed the following research questions: (1) what are the main combinations of services used by HACC clients aged 75–90 years, from 2001 to 2011, and (2) what are the factors associated with an increased risk of HACC use.

Methods

Study sample and data linkage

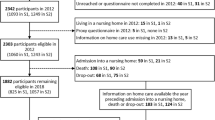

The 1921–1926 cohort of the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health (ALSWH) was recruited in 1996 with 12,432 women participating in the baseline survey (aged 70–75 years) (Loxton et al. 2015). ALSWH is a national population-based study of women’s health, with participants being randomly sampled from the Medicare Australia database. Data were collected from participants through self-reported postal questionnaires every third year until 2011 (Survey 1: 1996; Survey 2: 1999; Survey 3: 2002) and on a six-month rolling basis thereafter. Linked HACC data were not available before 2001. Consequently, the current study focused on the period from 2001 to 2011, whereby Survey 3 constituted the sample from which the baseline covariate characteristics (except educational qualification, measured only in Survey 1) were obtained. The total attrition by 2002 was N = 1237, with a response rate of 88%. Data from adjacent surveys (Survey 2 and Survey 4) were used to fill in missing values rather than using model-based imputation methods. A small proportion of missing values (≤ 5%) was not available in adjacent surveys. A detailed description of the ALSWH survey and its design has been previously published (Brilleman et al. 2010).

Survey data were linked with the administrative HACC Minimum Data Set (MDS) on an opt-out consent basis. In total, 11,133 women (> 95%) in the 1921–1926 cohort were eligible for data linkage, undertaken with the approval of the Australian Government Department of Health (DOH). The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIWH) used a probabilistic algorithm to link the ALSWH and HACC data sets (Karmel et al. 2010; National Statistical Services 2017).

This study was approved by the Human Research and Ethics Committee (HREC) of the University of Newcastle and University of Queensland. Ethical clearance for the linkage of ALSWH survey data with aged care data was approved by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare Ethics Committee.

HACC use

In total, 7747 women were identified as HACC users from July 2001 to December 2011. This dataset provided information on the quarterly use of HACC services for each client. Among the 28 service types, data on ‘HACC assessments’ and ‘carer services’ were not used in the current analysis. These two services were excluded as HACC assessment was related to the determination of eligibility for service provision (not an ongoing care type), while carer services were related to needs of the carers, rather than the care recipients. A range of minor services (including communication aids, self-care aids, support and mobility aids, reading aids, medical care aids, car modification, formal linen service, and other goods and equipment) were grouped under the ‘equipment and aids’ category. Accordingly, the number of service types included in our analysis was 19. Of these, 14 were characterized by hours of use, 4 by the frequency of use, and 1 by the amount of dollars expended (Department of Health and Ageing 2006) (Table 1).

Andersen–Newman model and participants’ baseline characteristics

The Andersen and Newman (2005) behavioural model was used to identify influencing factors associated with HACC use (Chen and Berkowitz 2012; Fu et al. 2017). While the model was originally introduced in 1968, it has evolved over time (Andersen 1968). In our analyses, individual/societal characteristics were grouped into three categories: predisposing factors (age, marital status, and education), enabling factors (income, living arrangements, and area of residence), and need factors (physical, psychological, and functional health status including illness and disability).

Demographic predisposing and enabling factors included area of residence (major cities, remote/inner/regional areas), country of birth (born in Australia, overseas), highest educational qualification (no formal, secondary certificate, high school/trade/diploma/university), marital status (married/de facto, widowed/divorced/never married/separated), living arrangements (living alone, living with partner/others including live with own children/other family members/non-family members), difficulty in managing income (easy/not too bad, difficult some/all the time), and Veterans’ Affairs coverage for health service use (yes, no). However, ALSWH did not include individual beliefs and community level enabling factors.

Health factors included diagnosed chronic conditions (e.g., heart problems, diabetes, arthritis, and asthma), falls with injury in the past 12 months, self-rated health (poor/fair, good/very good/excellent). Physical, social, and mental functioning scores were obtained from the SF-36 health-related quality of life, with row scores being computed from ten, two and five items, respectively. Scores were linearly transformed to produce subscale scores ranging from 0 to 100 (with a higher score indicating better health) (Ware et al. 1993). Based on the literature, scores above prescribed cut-off points corresponded to better functional capacity (e.g. physical function > 40, lower mental function > 52, and lower social function > 52) (ALSWH 2018; Stevenson 1996).

Statistical analyses

The data were analysed in two stages: the first was to identify which types of services women used, and the second was to identify factors associated with risk of first HACC use.

Cluster analysis

In the first stage, summary statistics regarding usage were computed for 19 HACC service types from 2001 to 2011. Z-scores were estimated to obtain a standardized metric for each service type. The distribution of usage was skewed for many service types. Accordingly, a robust k-median cluster analysis technique was applied to identify distinct groups of women based on their similarity with respect to the volume of HACC use (Anderson et al. 2006; Kendig et al. 2012; Sugar et al. 1998, 2004).

Clusters were formed by minimizing the Euclidian distance within a cluster and maximizing the differences between clusters (Aldenderfer and Blashfield 1984). Participants were grouped into mutually exclusive clusters based on the closeness (or similarity) of the volume of service use. In the current study, we used the Calinski/Harabasz pseudo-F statistic (PFS) value to determine the number of clusters (Caliński and Harabasz 1974).

Once clusters were identified, descriptive statistics (median with 95% confidence interval (CI) and proportions) were computed to explore service use patterns in each cluster. The clusters were given a descriptive name based on the volume, number, and type of services used. We divided the total participants (n = 11, 133) into three broad categories: ‘HACC non-users’, ‘basic HACC’ users, and ‘moderate- to high-level HACC’ users (included all distinct groups except Basic HACC). Chi-square tests were performed to explore associations between participants’ baseline characteristics and patterns of HACC use from 2001 to 2011.

Competing risk analysis

Women who were alive during Survey 3 and who had not used HACC before 2002 were included in the analysis (n = 9203). Age at first HACC use was measured from the begining of 2002, and if no HACC use was recorded, participants were censored at 31 December 2011 or their date of death. The maximum observation period was 120 months. Competing risk analysis was performed to obtain an accurate incidence of HACC use, wherein age at first HACC use was considered as the target variable with death as the competing event (Berry et al. 2010; Forder et al. 2017). Competing risks occur in a study when participants experience one or more events that compete with the event of interest (Noordzij et al. 2013). This study considered death as the competing event because participants are no longer at risk of using HACC after dying. Initially, crude hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated using Cox proportional hazard models (Fong et al. 2015). The adjusted model included demographic (predisposing and enabling) and health-related need factors that were significant in the unadjusted model, but excluded the SF-36 subscales and self-rated health. This was owing to a probable causal relationship with other health indicators included in the model. Four separate multivariable models were performed on self-rated health, physical, social, and mental functioning, adjusting for demographic variables. All the statistical tests were two-sided, and the level of significance was set at P < 0.05. Analyses were conducted using STATA/IC 15.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas, United States of America) and SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Distinct groups of HACC users

Approximately 70% (n = 7747) of women used HACC at some point during the study period. Six distinct groups of women were identified in our cluster analysis, where the number of groups was determined based on the PFS value of 283 and interpretability of the groups. The distinct groups were accordingly named based on the proportion of women using different HACC services and their median volume of service use (Table 1). While ‘basic HACC’ constituted the largest cluster of women (54%), this group had the lowest use of the 19 HACC services (shown in Column 1), compared with other clusters (P < 0.01). The median volume of each service use was lower than other groups. Approximately 51% women in the basic HACC group used one or two service types at some point over the study duration but not necessarily at the same time. More than 25% used three or four service types, and a negligible proportion (1%) used more than 10 services.

Nearly all women in the ‘basic domestic’ (n = 1280) and ‘complex domestic’ (n = 914) clusters used domestic assistance services. The former group used a lower volume of services, and a smaller proportion of them used other HACC services, than the latter group. For example, the median volume of domestic assistance used by the basic domestic group was 57 h, compared with 201 h used by the complex domestic group. Approximately one-third of the complex domestic group used 10 or more services. In contrast, only 9% of the basic domestic group used this amount (Table 2).

The other three groups were named ‘home meal’ (398 women), ‘complex nursing care’ (168 women), and ‘complex transport’ (814 women). Women belonging to the home meal group predominantly used meal services at home (100%), domestic assistance (72%), nursing care at home (62%), and a moderate volume and number of other services. All women in the complex nursing care group used nursing care (median = 189 h), while 63% used personal care (median = 54 h). The complex transport group primarily used transport services (92%; median = 129 instances), and centre-based day care (82%, median = 343 h). Women in the complex groups of ‘transport’, ‘nursing care’, and ‘domestic’ also frequently used other previously mentioned HACC services. More than one-third of women in the complex transport, complex domestic, and complex nursing care groups used 10 or more HACC service types, and ≤ 5% used one to two service types. The proportion of women using different HACC services differed between clusters (P < 0.01).

Demographic predisposing and enabling factors

There were key differences among the distinct clusters and for the broad categories including HACC non-users, basic HACC users, and moderate- to high-level HACC users (P < 0.05) (Table 3). The difference was especially pronounced among the broad categories. Higher proportions of women in the moderate- to high-level HACC user group were living in remote/inner/regional areas (62% vs. 50%, P < 0.01), widowed (53% vs. 46%, P < 0.02, P < 0.01), living alone (50% vs. 41%, P < 0.01), and having difficulty in managing income (31% vs. 22%, P < 0.01), than the HACC non-user group. A lower proportion of women who were receiving Veterans’ Affairs coverage used moderate- to high-level HACC than non-users (15% vs. 27%, P < 0.01).The main difference between HACC non-users and basic HACC users was area of residence (P < 0.01).

In the competing risk analysis with adjusting demographic and health-related factors, we found that women who lived in remote/inner/regional areas had 18% higher risk of using HACC than those who lived in major cities (Table 5). Being widowed (RR = 1.08, 95%CI = 1.03–1.14) and having difficulty some/all of the time in managing income (RR = 1.17, 95%CI = 1.10–1.23) were associated with an increased risk of using HACC compared with their respective counterparts. Furthermore, those who received Veterans’ Affairs coverage were 36% less likely to use HACC than those who did not receive such coverage (P < 0.01).

Health-related need factors

The median physical and social functioning scores on the SF-36 health-related quality of life scale differed by the three broad HACC groups (P < 0.01). For example, the respective scores for basic HACC users were ‘63 and 88’, ‘50 and 75’ for moderate- to high-level HACC users, and ‘70 and 100’ for HACC non-users were 70 and 100 (Table 4). Consequently, an increased proportion of women who belonged to basic HACC and moderate- to high-level HACC (compared with HACC non-users) had physical, social, and mental health scores below the cut-off points (≤ 40, ≤ 52, and ≤ 52, respectively). The proportions of women who had chronic conditions were higher among both basic HACC and moderate- to high-level HACC users, than HACC non-user (P < 0.01).

Health-related need factors were significantly associated with the use of HACC, after controlling for demographic factors and counting death as a competing event (Table 5). Women diagnosed with chronic conditions (e.g., heart problems, diabetes, asthma, arthritis) had an increased risk of using HACC than their respective counterparts.Women who reported lower scores for physical, social, and mental functioning on the SF-36 health-realted quality of life scale had 54%, 53%, and 33% increased risk of using HACC services, than those who had higher scores in their respective domains (P < 0.01). Furthermore, women who reported poor/fair self-rated health had 56% increased risk of using HACC than those who reported good/very good/excellent self-rated health (P < 0.01).

Discussion

The cluster analysis identified six distinct groups of HACC clients based on their volume/number of services used from 2001 to 2011. Statistical techniques may not always provide a definite number of meaningful clusters when units with distinct characteristics group together (Sugar et al. 2004). However, we were able to clearly delineate (by volume, number, and type) distinct patterns of service use among HACC users. Over the 11 years of the study, the majority of women used few HACC services and typically with a low volume. In contrast, approximately one-fourth of women used complex patterns of care with high volume and number of services. More than one-third of women in the complex groups used 10 or more service types, indicating their multifaceted care needs. However, participants may not have concurrently used the entire range of services over the study period.

Researchers in another Australian study found that approximately three-fourths of clients used a small number, but a wide range of services (Kendig et al. 2012). In their study, only 8% of people used complex patterns of services. Their findings were consistent with other studies in Australia and the United States, suggesting that few older people received an intensive amount of community-based health and social care services (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2007; Choi et al. 2006; Kendig et al. 2012). The variation with the current analysis was attributed to participants’ age, gender, and study period. For example, the former Australian study focused on both men and women from the 45 and Up Study, and only considered a short period (2006–2008). In contrast, our study focused on women aged 75 to 90 years and identified a greater proportion of women who had complex patterns of HACC use. This is consistent with the literature, suggesting that people in their eighties are more likely to experience multiple morbidities/disabilities and to be increasingly dependent on formal care services (Austad 2009; Stones and Gullifer 2016).

We observed that living in inner/regional/remote areas or alone or having difficulty in managing income were associated with an increased risk of moderate or complex patterns of HACC use. Our findings are in agreement with another study observing that HACC use was associated with living in a remote/regional area, not having a partner, having a lower household income and not having paid work (Jorm et al. 2010). Greater use of HACC services in remote/regional areas reflects a limited access to residential aged care in those areas. Women who had financial difficulties were less likely to use high-cost residential aged care, but instead were more dependent on low-cost HACC services. In some cases, women may not have used services provided by HACC if they had overlapping coverage under the Veterans’ Home Care scheme (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2008b).

Our findings illustrate that health-related need factors among older women are associated with different patterns of HACC use. For example, comorbid conditions were associated with poor physical functioning and disability, which may have contributed to greater aged care needs. Lower physical functioning scores also were predictive of the need for physical care support. These results are consistent with other studies that report greater HACC use among older people with lower physical functioning, poorer self-rated health, and having chronic conditions (Jorm et al. 2010; Rochat et al. 2010).

For example, low physical functioning scores (< 40) have been associated with fear of falls and an increased risk of using age care services (Cumming et al. 2000). Below this score, women often have difficulty performing vigorous activities such as walking one-kilometre, climbing stairs, having lifting/carrying. Furthermore, approximately one-third of women have difficulty walking 100 metres and 10% will require assistance with dressing and bathing (Hubbard et al. 2017). These findings have important implications for improving service delivery, such as targeting a group of women with specific needs. Future research is needed to better understand the transitions of older women between different levels of service use over time, and whether they receive services in an appropriate and timely manner.

An important strength of our study was the use of a large longitudinal survey of older women in Australia, which was linked with administrative aged care data sets. However, our findings must be considered in light of a few limitations. For example, we focused only on women who generally receive formal support in the community aged care setting for a longer time than men, with the latter entering permanent RAC at an earlier time point (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2018). Additionally, we were unable to establish whether HACC services were sufficient to fully meet the needs of recipients and if such services were provided in a timely fashion. Closer observation of assessed and met needs would be required to make this judgement. Our study also did not consider changes in service use over time in accordance with their evolving care needs.

Conclusions

In the current study, we observed significant diversity in the patterns of HACC use among older Australian women, according to their demographic and health characteristics. Our findings highlight that many older women can remain living at home independently, requiring only a low-level use of a few basic community care services. However, approximately one-fourth of service users have complex care needs requiring a greater use of multiple HACC services. Finally, our study provides a baseline against which recent reforms and structural changes in community care services can be assessed.

References

Aldenderfer MS, Blashfield RK (1984) Cluster analysis: quantitative applications in the social sciences. Sage Publication, Beverly Hills

ALSWH (2018) The SF-36. Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health. http://www.alswh.org.au/images/content/pdf/InfoData/Data_Dictionary_Supplement/DDSSection2SF36.pdf. Accessed 26 Oct 2018

Andersen RM. (1968) Families’ use of health services: a behavioral model of predisposing, enabling and need components [dissertation]. Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN. http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/dissertations/AAI6902884/. Accessed 17 Jan 2019

Andersen R, Newman JF (2005) Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. Milbank Q. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00428.x

Anderson BJ, Gross DS, Musicant DR, Ritz AM, Smith TG, Steinberg LE Adapting k-medians to generate normalized cluster centers. In: SDM, 2006. SIAM, pp 165–175

Austad SN (2009) Comparative biology of aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 64:199–201. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/gln060

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2007) Older Australian at a glance, vol 4. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), Canberra

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2008a) Aged care packages in the community 2006–07: a statistical overview, vol 27. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Canberra

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2008b) Veterans’ use of health services, vol 13. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Canberra

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2014) Patterns in use of aged care: 2002–03 to 2010–11. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Canberra

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2015) Australia’s welfare 2015. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Canberra

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2017) Pathways to permanent residential aged care, vol Cat. no. AGE 81 Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), Canberra

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2018) GEN fact sheet 2015–16: people leaving aged care. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Canberra

Berry SD, Ngo L, Samelson EJ, Kiel DP (2010) Competing risk of death: an important consideration in studies of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 58:783–787. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02767.x

Brilleman SL, Pachana NA, Dobson AJ (2010) The impact of attrition on the representativeness of cohort studies of older people. BMC Med Res Methodol 10:71

Caliński T, Harabasz J (1974) A dendrite method for cluster analysis. Commun Stat Theory Methods 3:1–27

Chen Y-M, Berkowitz B (2012) Older adults’ home-and community-based care service use and residential transitions: a longitudinal study. BMC geriatr 12:44

Choi S, Morrow-Howell N, Proctor E (2006) Configuration of services used by depressed older adults. Aging Ment Health 10:240–249

Cumming RG, Salkeld G, Thomas M, Szonyi G (2000) Prospective study of the impact of fear of falling on activities of daily living, SF-36 scores, and nursing home admission. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 55:M299

Department of Health and Ageing (2006) Home and community care program national minimum dataset user guide version 2. Canberra

Department of Health and Ageing (2008) Ageing and aged care in Australia. Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, Canberra

Department of Health and Ageing (2012) Commonwealth HACC program guidelines. Canberra

Department of Social Services (DSS) (2014) Home and Community Care Program Minimum Data Set 2013–14 Annual Bulletin. Department of Social Services (DSS), Canberra

Department of Work and Pensions (2007) Opportunity for all: indicators update 2007. Department of Work and Pensions, London

EUROBAROMETER (2007) Health and long-term care in European Union. European Commission, Brussels

Fong JH, Mitchell OS, Koh BS (2015) Disaggregating activities of daily living limitations for predicting nursing home admission. Health Serv Res 50:560–578. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12235

Forder P, Byles J, Vo K, Curryer C, Loxton D (2017) Cumulative incidence of admission to permanent residential aged care for Australian women–a competing risk analysis. Aust N Z J Public Health 24:166–171

Francesca C, Ana L-N, Jérôme M, Frits T (2011) OECD health policy studies help wanted? Providing and paying for long-term care: providing and paying for long-term care, vol 2011. OECD Publishing, Paris

Fu YY, Guo Y, Bai X, Chui EW (2017) Factors associated with older people’s long-term care needs: a case study adopting the expanded version of the Anderson Model in China. BMC Geriatr 17:38. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-017-0436-1

Genet N, Boerma WG, Kringos DS, Bouman A, Francke AL, Fagerström C, Melchiorre MG, Greco C, Devillé W (2011) Home care in Europe: a systematic literature review. BMC Health Serv Res 11:207

Hubbard IJ, Wass S, Pepper E (2017) Stroke in older survivors of ischemic stroke: standard care or something different? Geriatrics 2:18

Jeon YH, Kendig H (2017) Care and support for older people. In: O’Loughlin CB K, Kendig H (eds) Ageing in Australia: challenges and opportunities. Springer, New York, pp 239–259

Jorm LR, Walter SR, Lujic S, Byles JE, Kendig HL (2010) Home and community care services: a major opportunity for preventive health care. BMC Geriatr 10:26. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-10-26

Karmel R, Anderson P, Gibson D, Peut A, Duckett S, Wells Y (2010) Empirical aspects of record linkage across multiple data sets using statistical linkage keys: the experience of the PIAC cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res 10:41. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-10-41

Keleher H (2003) Community care in Australia. Home Health Care Manag & Pract 15:367–374

Kendig H, Mealing N, Carr R, Lujic S, Byles J, Jorm L (2012) Assessing patterns of home and community care service use and client profiles in Australia: a cluster analysis approach using linked data. Health Soc Care Community 20:375–387. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2524.2011.01040.x

Laditka SB, Laditka JN (2001) Effects of improved morbidity rates on active life expectancy and eligibility for long-term care services. J Appl Gerontol 20:39–56

Lafortune L, Beland F, Bergman H, Ankri J (2009) Health state profiles and service utilization in community-living elderly. Med Care 47:286–294. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181894293

Lowenstein A, Katz R, Prilutzky D, Mehlhausen-Hassoen D (2001) The intergenerational solidarity paradigm. In: Aging, intergenerational relations, care systems and quality of life, NOVA Rapport, pp 11–30

Loxton D, Powers J, Anderson AE, Townsend N, Harris ML, Tuckerman R, Pease S, Mishra G, Byles J (2015) Online and offline recruitment of young women for a longitudinal health survey: findings from the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health 1989–95 cohort. J Med Internet Res. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.4261

McCann M, Donnelly M, O’Reilly D (2012) Gender differences in care home admission risk: partner’s age explains the higher risk for women. Age Ageing 41:416–419. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afs022

Merlis M (2000) Caring for the frail elderly: an international review. Health Aff (Millwood) 19:141–149

National Statistical Services (2017) Statistical data integration involving Commonwealth data. The Australian Government. http://www.nss.gov.au/nss/home.nsf/pages/Data%20integration%20-%20data%20linking%20information%20sheet%20four. Accessed 12 Nov 2017

Noordzij M, Leffondré K, van Stralen KJ, Zoccali C, Dekker FW, Jager KJ (2013) When do we need competing risks methods for survival analysis in nephrology? Nephrol Dial Transplant 28:2670–2677

Palmer GR, Short SD (2000) Health care and public policy: an Australian analysis. Macmillan Education, Australia

Productivity Commission (2011) Caring for older Australians, vol 1&2. The Productivity Commission, Canberra

Rochat S, Cumming RG, Blyth F, Creasey H, Handelsman D, Le Couteur DG, Naganathan V, Sambrook PN, Seibel MJ, Waite L (2010) Frailty and use of health and community services by community-dwelling older men: the Concord Health and Ageing in Men project. Age Ageing 39:228–233

Stevenson C (1996) SF-36: Interim norms for Australian data Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia, Canberra

Stones D, Gullifer J (2016) ‘At home it’s just so much easier to be yourself’: older adults’ perceptions of ageing in place. Ageing Soc 36:449–481. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X14001214

Sugar C, Sturm R, Lee TT, Sherbourne CD, Olshen RA, Wells KB, Lenert LA (1998) Empirically defined health states for depression from the SF-12. Health Serv Res 33:911

Sugar CA, James GM, Lenert LA, Rosenheck RA (2004) Discrete state analysis for interpretation of data from clinical trials. Med Care 42:183–196

UNDESA (2015) World population ageing 2015. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division, New York

Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M, Gandek B (1993) SF-36 Health Survey. Manual and interpretation guide. The Health Institute, New England Medical Center, Boston

Wouterse B, Huisman M, Meijboom BR, Deeg DJ, Polder JJ (2015) The effect of trends in health and longevity on health services use by older adults. BMC Health Serv Res 15:574. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-1239-8

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted as part of the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health, University of Newcastle and University of Queensland. The authors are grateful to the Australian Government Department of Health for funding and for providing permission to access the aged care datasets, and to the women who provided the survey data. The authors acknowledge the assistance of the data linkage unit at the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) for undertaking the data linkage to the National Death Index (NDI) and administrative aged care data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Additional information

Responsible editor: Susanne Iwarsson

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rahman, M., Efird, J.T., Kendig, H. et al. Patterns of home and community care use among older participants in the Australian Longitudinal Study of Women’s Health. Eur J Ageing 16, 293–303 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-018-0495-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-018-0495-y