Abstract

Instruments with acceptable measurement properties that support their application to older adults across a range of settings need to be identified. A narrative literature review of empirical studies investigating the conceptualization and measurement of quality of life (QoL) among older adults from 1994 to 2006 was performed. The review focused on evidence provided for conceptual frameworks, QoL definitions, types of measurements utilized and their psychometric properties. Two searches were conducted. The first search conducted in 2004 used Cinahl, Medline, PsycInfo, Embase and Cochrane databases. A supplemental search was conducted in December 2006, which included these bases from 2004 to 2006, and Sociological Abstracts and Anthropological literature base. The review included 47 papers. A total of 40 different measurements were applied in the studies, assessing most frequently functional status and symptoms. The most extensive psychometric evidence was documented for the SF-36. Although construct validity was reported in the majority of studies, minimal empirical evidence was given for other psychometric properties. Further, 87% of the studies lacked a conceptual framework and 55% did not report any methodological considerations related to older adults. Quality control standards, which can guide measurement assessment and subsequent data interpretation, are needed to enhance more consistent reporting of the psychometric properties of QoL instruments utilized. Future work on the development of common QoL assessment models that are both person-centered, causal and multidimensional based on collaborative efforts from professionals interested in QoL from the international gerontological research community are needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The evaluation of QoL among older adults has become increasingly important in health and social sciences. This is due not only to the growing numbers of older adults, but also to the eradication of most infectious diseases; the dominance of chronic, degenerative diseases as populations age; impressive medical technological progress; the necessity for making the effects of medical treatment more explicit; and the demand for indicators of well-being, including psychological and social aspects (Higgs et al. 2003; Walker 2005a, b, c). Research on QoL expanded especially during the 1990s, resulting in over a hundred definitions of QoL (Cummins 1997), and more than 1,000 measures of various aspects of QoL (Hughes and Hwang 1996).

Conceptualization of QoL

Although QoL research has increased in methodological rigor, progress has been hindered by the fact that QoL has been used to mean a variety of different things. There seems to be no widely accepted theoretical framework for QoL or a general consensus concerning which areas are necessary for any comprehensive definition among adults. The question has been raised whether the conceptualization of QoL among older adults is the same as for younger, middle-aged adults (Bowling 2001a; Brown et al. 2004; Power et al. 2005; Walker 2005c).

Classic conceptualizations of QoL in all adults have included such domains as physical health, social relationships and support, environment, financial and material circumstances, and cognitive beliefs (Andrews and Withey 1976; Campbell et al. 1976; Flanagan 1978; George and Bearon 1980). Currently, most researchers are in agreement that QoL among older adults reflects a multidimensional concept, including physical, emotional and social domains (Bowling 2001a; Brown et al. 2004; Ellingson and Conn 2000; Haywood et al. 2004; Moons 2004).

Further, the position has been taken that QoL should be studied from the perspective of the individual (Andrews and Withey 1976; Calman 1987; Taylor and Bogdan 1990; Walker 2005c), although it has been suggested that lay views of older adults has not been given enough consideration when measuring QoL (Brown et al. 2004; Haywood et al. 2004; Repetto et al. 2001). Researchers have been specifically challenged to avoid measures of QoL that exclude or ineffectively explore areas that are important to older adults, or worse, lead to disadvantages in the allocations of health resources (Frytak 2000; Noro and Aro 1996). For example, authors report that a paucity of attention has been given to assessing important areas such as transitions from employment to retirement, from responsible duties to free time, integration into retired community activities, alterations in family and friends, issues of intimacy, and spiritual concerns including death and dying (Farquhar 1995; Nilsson et al. 1998; O’Boyle 1997; Power et al. 2005). Further, a recent review found that older people consistently nominated components as relationships with family and others, independence and autonomy, finances, health, spirituality, and institutional care as important (Brown et al. 2004).

Measurement issues

The measurement of QoL has become more complicated because the term “health-related quality of life” (HRQoL) has evolved. Citations in Medline of this term go back to 1989. Although this term is intended to focus on the effects of health, illness and treatment on aspects of life QoL (De Korte et al. 2004; Ferrans et al. 2005; Fries 1983; Hyland 1992; White 1967), both HRQoL and QoL as concepts include many of the same domains and literature supports problems in their differentiation (Farquhar 1995; Frytak 2000; Gill and Feinstein 1994). QoL and HRQoL are concepts that are often used interchangeably in discourse and in outcomes measurement, although it is generally agreed that QoL is considerably more comprehensive than HRQoL and includes aspects of the environment that may or may not be affected by heath and treatment (Patrick and Chiang 2000). Traditionally, the concept of HRQoL was meant to distinguish outcomes relevant to health research from earlier sociological research on subjective well-being and life satisfaction in healthy general populations (Campbell et al. 1976). Currently, words such as happiness, life satisfaction and subjective well-being are still described as being closely aligned with QoL but not including QoL (Sirgy et al. 2006).

Another measurement issue regarding older adults includes a scarcity of older adult-specific instruments for QoL assessment (Frytak 2000; Haywood et al. 2004; Hendry and McVittie 2004; Power et al. 1999).Traditionally, QoL in older adults has been measured by generic QoL/HRQoL instruments applied to younger, middle-aged samples, and oftentimes inappropriately applied (Hendry and McVittie 2004). For example, using measures which only assess “ill health” and using domains which are irrevalent (Bowling 2001a; Ellingson and Conn 2000; Fayers and Machin 2007).

It has also been recommended that when assessing QoL, instruments should be evaluated for their psychometric properties such as reliability and validity and responsiveness to important clinical changes in various populations (Deyo et al. 1991; Ettema et al. 2005; Haywood et al. 2004; Patrick and Chiang 2000; Scientific Advisory Committee of the Medical Outcomes Trust 2002). Also, considerations should be given to response burden, understandability of the items and features of score distributions (McHorney 1996). Moreover, the correspondence between QoL and underlying theoretical origins, conceptual models of relationships, concept definitions and reasons for instrument choice should be considered (Brown et al. 2004; Haywood et al. 2004; Patrick and Chiang 2000).

Special considerations in assessment

Other methodological considerations regarding older adults include physical, mental, and functional changes taking place in this population. The specificity of these changes, and how these changes appear, are dependent upon aging phases, transitions, and medical conditions (O’Boyle 1997), lifestyle characteristics (Ellingson and Conn 2000; Parse 2003), personality (Erikson and Erikson 1997; Kempen et al. 1999; Krause 2004), psychological factors (Bowling 2005; Brown et al. 2004), coping capacity (Kempen et al. 1999), and social relationships (Bowling 2005; Walker 2005a). Many older adults suffer from cognitive impairment. The measurement of cognitive status demands special attention (Ettema et al. 2005; Fors et al. 2006; Grundy 2006; Haywood et al. 2004; Kane et al. 2002; Walker 2005a). Also, older adults often experience co-morbidity together with normal ageing processes, necessitating the need for the assessment of sensory changes (Østby 2004; World Health Organization 2000). Problems including educational level, sight, hearing, communication, and fatigue also demand special concern in measurement administration and instrument adaptation (Bowling 2001a; Haywood et al. 2004, 2005a, b; Kane et al. 2002; Tidermark et al. 2004).

During the last 10 years, there has occurred a growth in studies describing the assessment of QoL and HRQoL amongst older adults (Brand et al. 2004; Brazier et al. 1996; Grimby and Wiklund 1994). Haywood’s reviews have identified a increase in the number of instrument evaluations with older adults particularly since 2000 (Haywood et al. 2004, 2005a, b). However, these authors, together with others, recommend continual evaluation of existing generic instruments in this age group (Brown et al. 2004; Buck et al. 2000; Ettema et al. 2005).

Aim

The aim of this paper is to conduct a narrative review of the conceptualization and the measurement properties of QoL instruments used in empirical studies among older adults from 1994 to 2006.

Search method

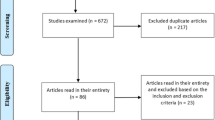

The sample consisted of all studies meeting the inclusion criteria published from 1994 to 2006. A literature search in Medline, Cinahl, Embase, PsycINFO and Cochrane databases was undertaken in May 2005. In January 2007, a supplemental search was conducted covering the years 2005–2006 in these same bases, and also including Sociological Abstracts and Anthropological literature base for the period 1994–2006. In both searches the keywords, “quality of life, elderly, measurement, measurement scale, health-related, and assessment” were used to identify the corresponding controlled vocabulary system within each database. A controlled vocabulary system is a carefully selected list of words and phrases, which are used to tag units of information (document or work) so that they may be more easily retrieved by a search (Craig and Smyth 2002). The Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) system used by the Medline database is an example of a controlled vocabulary system (Gault et al. 2002). With the databases Medline, Cinahl, Embase, PsycINFO and Cochrane the word “elderly” is defined as the subject heading “aged”. We use the definition of aged as defined in Medline “A person 65 through 79 years of age” and “aged, 80 and over”, also supported by others (Bowling 2001a; Bowling et al. 2002).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Titles and abstracts of all articles were assessed for inclusion/exclusion criteria by two reviewers. Articles included were retrieved in full. Publications were included in this paper if they met the following inclusion criteria: (1) addressed older adults 65 years or older, (2) the authors explicitly state they intend to measure QoL and/or HRQoL, and (3) written in English or Scandinavian language. Publications were excluded when: (1) authors did not explicitly use the term “ QoL or/HRQoL” and used other words such as mortality, life-satisfaction, happiness, well-being, or functional status, (2) QoL was pointed out for further investigating in new studies, (3) proxy informants were used, (4) age classification was under 65 for a part of or the whole sample, (5) review articles, (6) articles in the form of concept analyses, letters, commentaries, and abstracts relating to posters and oral presentations (7) articles with qualitative design, (8) not English or Scandinavian language, and (9) not within the period 1994–2006. Articles were excluded on the basis of their abstracts and reading full article texts.

Data extraction

Data extraction followed criteria considered important in instrument evaluation discussed by several authors. These criteria include: evidence given for an underlying conceptual model in the study, concept definitions, internal consistency, reproducibility, responsiveness, floor and ceiling effects, content and construct validity, interpretability and acceptability (Andresen 2000; Bowling 2001a, b; Bowling and Ebrahim 2005; Brown et al. 2004; Fitzpatrick et al. 1998; Fletcher et al. 1992; Haywood et al. 2004, 2005a; McHorney 1996; Patrick and Chiang 2000; Scientific Advisory Committee of the Medical Outcomes Trust 2002; Streiner and Norman 2003, 2006; Terwee et al. 2007; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration 2006). Special considerations related to domains covered, age-specific areas, cognitive status, administration, and instrument adaptation were also extracted.

A conceptual model is a set of interrelated concepts or abstractions that are assembled together in some rational scheme by virtue of their relevance to a common theme; it is also referred to as a conceptual or theoretical framework. A conceptual framework can also be shown as a diagram or schema, with a set of related concepts and the linkages among them displayed by the use of boxes and arrows (Gerritsen et al. 2004; Polit and Beck 2004). The use of theory assumes that a conceptual model is utilized (Chinn and Kramer 1999). In the review, criteria for assessing evidence of a conceptual model included that QoL or HRQoL was the major construct used in connection to a specific theory named in a model, and/or the authors provided a schematic model which pictorially represented the QoL or HRQoL concepts and/or interrelationships.

Various types of psychometric criteria have been defined. Reliability summarizes the measurement’s consistency measuring internal consistency and evidence is shown with values of Cronbach’s α 0.70 and over (Bowling 2001a; Fitzpatrick et al. 1998; Nunnally and Bernstein 1994). Another form of reliability is examined by test–retest reproducibility, assessing score consistency over two points in time (Bowling and Ebrahim 2005). A kappa test, Pearson’s correlations, Spearmans’s rho, Kendall’s tau and Intraclass correlations coefficient (ICC) may be used as evidence to assess the extent to which the results obtained by two or more raters or interviewers are in agreement for the same populations (Bowling and Ebrahim 2005). There is no standard level of the reliability coefficient (Polit and Beck 2004). It is common to recommend 0.90 if the measurement is to be used for evaluating individuals and 0.70 when discriminating between groups (Fayers and Machin 2007; Polit and Beck 2004), although Fayers (2007) referrers to values of 0.60 and even 0.50 as acceptable. Altman (1999) suggests a kappa value <0.20 to be poor evidence. The ICC, expressed as a ratio between 0 and 1 (Terwee et al. 2007), demonstrates evidence that is mathematically equivalent to the unweighted kappa statistic (Streiner and Norman 2003).

Responsiveness to change, sometimes called sensitivity, has been examined as a third category in addition to reliability and validity (Bowling and Ebrahim 2005; Fitzpatrick et al. 1998). Some consider responsiveness to be related mathematically to reliability, and on the conceptual level, as an aspect of validity (Patrick and Chiang 2000; Streiner and Norman 2003; Terwee et al. 2003). Validity is understood as a measurements power to measure clinically important change over time, the most common evidence being the effect size statistic (Haywood et al. 2006; Streiner and Norman 2003; Terwee et al. 2003). Also, where more than 20% of the responders have the minimum or maximum score, the score distribution indicates floor or ceiling effects, which reduce reliability and threaten responsiveness of the measurement (Haywood et al. 2005a).

Streiner and Norman (2003) reported differences in definitions of validity. As recommended, we use the concepts; content and construct validity. Validity summarizes the degree to which a measurement measures what it is supposed to measure. Evidence for face and content validity requires a more qualitative approach to assess the underlying relationship between the items and the theoretical base, the intended purpose, or intended use of the measurement (Haywood et al. 2006). Construct validity, understood as convergent or discriminant validity, requires that the instrument display evidence of correlations with related but not with dissimilar variables (Bowling and Ebrahim 2005; Streiner and Norman 2003). Factor analysis is the most common statistical method for examining the construct validity (Fitzpatrick et al. 1998).

Interpretability is defined as the degree to which one can assign meaning to a measurement’s qualitative score. Interpretability can be assessed by comparing the data with representative data from the general population (normative data) (Fitzpatrick et al. 1998; Terwee et al. 2007). Instrument acceptability addresses the willingness of people to complete an instrument (Fitzpatrick et al. 1998). Evidence of acceptability can be explored by such characteristics as response rate, missing values, response burden and mode of administration.

Findings

The review generated 499 articles from the seven databases. Only 47 articles were found to be relevant for the purpose of this article (Table 1). Articles were most often excluded because they did not meet the age-related criteria (65%), did not focus on QoL (13%), or were written in non-English or non-Scandinavian languages (6%).

Evaluation of studies

The variability of the 47 evaluated studies was large in terms of conceptual frameworks, definitions and measurements utilized, cited psychometric properties, and special considerations given to assessment issues among older adults.

Conceptual frameworks of QoL

A conceptual framework was found in only 13% of the studies (Beaumont and Kenealy 2004; Grundy and Bowling 1999; Higgs et al. 2003; Nesbitt and Heidrich 2000; Sarvimaki and Stenbock-Hult 2000). Of the six studies reviewed, Grundy and Bowling (1999) described QoL in relation to different models of human needs, as reflected in Maslow’s theory (1954), and satisfaction with life and happiness as accompanying successful aging. These authors underscored the broad and multidimensional perspective of well-being in old age, with the assumption that QoL covers all aspects in life. Nesbitt and Heidrich (2000) proposed a model of QoL, positing interrelationships among physical health limitations, sense of coherence, illness appraisal and QoL. Sarvimaki and Stenback-Hult (2000) applied a model of QoL based upon the definition of QoL as “a sense of well being, of meaning, and of value or self-worth” (p. 1027). These authors suggested that QoL is influenced by intra-individual characteristics, such as health, functional capacity and coping mechanisms and external conditions including environment, work, housing conditions and social network. Fry (2001) used social-cognitive theory in a study predicting HRQoL among older adults losing the spouse, and stated that “self-efficacy beliefs or expectancies of elderly individuals influence the level of effort they expend to preserve their QoL” (p. 788). Aspects of contemporary social theory as reflected in models based upon social comparison strategies and need satisfaction (control, autonomy, pleasure and self realization) were also applied (Beaumont and Kenealy 2004; Higgs et al. 2003).

Definitions of QoL

Of the reviewed studies, QoL was reportedly measured by 58%, 36% reported HRQoL measurement, and 6% stated that both QoL and HRQoL was examined (Table 1). In 43% of the studies QoL or HRQoL was actually defined. Sometimes, the concepts of QoL and HRQoL were used to mean the same thing. For example, the SF-36 is described as both a QoL and HRQoL measurement (Akifusa et al. 2005; Berkman 1999; Berlowitz 1995; Brazier et al. 1996; Byles 1999; Byles et al. 2004; Gagnon et al. 1999; Hanlon et al. 1996; Jenkins 2002; McFall 2000; Nelson et al. 2004; Peek 2004; Pfisterer et al. 2003; Reeves et al. 2004; Varma et al. 1999). Various authors define QoL broadly, while others do not make a distinction between QoL and HRQoL (Bowling et al. 2002; De Leo et al. 1998; Hellstrom et al. 2004b; McHugh et al. 1997; Nesbitt and Heidrich 2000). One study, Noro and Aro (1996, p. 355–356) defined both concepts. In some studies, HRQoL was reflected by the study aims and measurements chosen (Berlowitz 1995; Brazier et al. 1996; MacRae et al. 1996; Peek 2004).

QoL measurements and domains

Wilson and Cleary (1995) have developed a conceptual model for HRQoL outcomes that has increased in popularity (Ferrans et al. 2005; Patrick and Chiang 2000). We have used this model to categorize measurements and domain areas described in the review. Basically, the model depicts relationships among biological and physiological variables, symptom status, functional status, general health perceptions and overall QoL (Table 2). A total of 40 different measurements were reported, with 34 instruments applied in single studies and six instruments used in more than one study. The SF-36 (36%) and SF-12 (11%) were most frequently used. The Life Quality Gerontological Centre Scale (LGC) was used in 9%; and the Nottingham Health Profile (NHP), EuroQol and Sickness Impact Profile (SIP) each in 4% of the studies. Two studies provided evidence for assessing lay views and personal importance given to various domains by using the Schedule for Evaluation of Individual Quality of Life: direct weighting (SEIQoL–DW) and the Modified Patient Generated Index (MPGI). According to Wilson and Cleary’s (1995) model none of the measurements met the criterion for all the five levels. The SF-36 and SF-12 included four of the five levels in the model, exhibiting greatest multidimensionality in their assessment (see references in Table 3). Further, 22 instruments assessed functional status factors and 15 instruments assessed symptom status factors. Only four measurements assessed biological–physiological variables that appeared in the same study (Kumar et al. 1995). Assessments measuring Overall QoL and general health perceptions were included 16 and seven studies, respectively. Additional domains and content areas were assessed by 17 of the measurements and included the following; religion/spirituality (spiritual life, meaning, purpose, important areas of life), independence, mobility and autonomy (autonomy, respected by others, environment), enabling activities (control, pleasure, self realization, capacity, sense of coherence) social/leisure activities and community (work, interests, hobbies, holidays, work, retirement), finances/standards of living (economy, economic dimensions), and health (common health complaints, self-reported diseases, subjective impact of disease, sexual activity, ADL, disability).

Psychometric properties reliability and validity

Internal consistency and reproducibility are reported for 14 of the 40 measurements utilized. Internal consistency reliability is reported for ten instruments (Table 4). Unacceptable reliability coefficients with Cronbach’s alpha below 0.70 were reported in Berlowitz (1995) and Brazier et al (1996) for the SF-36, in Hellstrøm et al. (2004a) for the SF-12, in Hellstrøm et al. (2004a) for the LGC, in De Leo et al. (1998) for the LEPAD, and in Bowling et al. (2002) for the QoL survey questionnaire. Reproducibility was reported by acceptable values by Brand et al (2004) with kappa value (0.79) for the assessment of QoL instrument; by Lui-Ambrose (2005) for the QUALEFFO with kappa values (0.54–0.90), test–retest (r = 0.99), and ICC (0.83); and by Brazier (1996) with Spearman for the EuroQol (r = 0.53) and partly for the SF 36 (r = 0.28–0.70). Responsiveness to change (effect size) was reported for the SF-36 (Berkman 1999; Brazier et al. 1996; Byles et al. 2006, 2004; Hanlon et al. 1996), EuroQol (Brazier et al. 1996), SIP (Fletcher et al. 2004), and the QUALEFFO (Liu-Ambrose et al. 2005). Floor effects were reported for SF-36, EuroQol, and the control autonomy pleasure self realization (CASP) (Berkman 1999; Brazier et al. 1996; Higgs et al. 2003).

Evidence for construct validity was reported for all measurements except for the QUALEFFO (Liu-Ambrose et al. 2005). Of those reporting construct validity, 16 measurements provided evidence of convergent validity, 34 discriminate validity, and ten factor analysis. Face-content validity was assessed in nine measurements belonging to six studies (Berlowitz 1995; Bowling et al. 2002; Brazier et al. 1996; Grundy and Bowling 1999; Higgs et al. 2003; Sarvimaki and Stenbock-Hult 2000).

Evidence of acceptability was assessed by response rate, missing values, removal of items based on focus work, and clarification that the older adults were too frail or cognitively impaired to answer items (Andersson et al. 2006; Brand et al. 2004; Brazier et al. 1996). Interpretability, as evidenced by normative comparisons, was reported for the SF-36, SF-12, LGC and the EuroQol (Akifusa et al. 2005; Berkman 1999; Borglin et al. 2005; Byles 1999; Byles et al. 2004; Peek 2004; Stenzelius et al. 2005; Tidermark et al. 2004).

Special considerations for the assessment of QoL among older adults

Special considerations given to domain coverage, age-specific areas, cognitive status, and administration method and instrument adaptation were reviewed. Of the studies, 55% did not provide any evidence of age-specific content considerations given to the assessment of QoL among older adults and a large majority (89%) of the studies did not discuss any special considerations given to instrument adaptation. However, all studies reported the administration method. Two-thirds (62%) used face-to-face interviews separately or combined with other methods, and 11% used phone interviews. Evidence for sensory changes in relation to vision and hearing impairment was cited only once, in spite of the fact that 80% of individuals over 60 years are visually impaired, 22% experience impairment in both vision and hearing, which can complicate self or telephone completion of questionnaires (Haywood et al. 2004).

In the studies that reviewed age-specific areas, discussion was focused on physical or physiological changes (Berlowitz 1995; Brazier et al. 1996; Grimby and Wiklund 1994; Liu-Ambrose et al. 2005; Stenzelius et al. 2005); role and developmental changes (Grimby and Wiklund 1994; Grundy and Bowling 1999; Noro and Aro 1996; Sarvimaki and Stenbock-Hult 2000); cognitive and mental functioning (Brazier et al. 1996; De Leo et al. 1998; Noro and Aro 1996); changes in social network (Dempster and Donnelly 2000); changes in functional ability (Borglin et al. 2005; Liu-Ambrose et al. 2005; Stenzelius et al. 2005); need for control, autonomy, pleasure, and self-realization (Higgs et al. 2003); pain (Liu-Ambrose et al. 2005); residential arrangements and social comparison processes (Beaumont and Kenealy 2004); and sight, hearing, communication, and fatigue as considerations in administration (Tidermark et al. 2004). Also, considerations given to education, value orientations, work, and an understanding of health as differing from younger samples were made (Beaumont and Kenealy 2004; Berlowitz 1995; Bowling et al. 2002; Brazier et al. 1996; Byles 1999; De Leo et al. 1998; Higgs et al. 2003).

Cognitive status was measured in only 11% of the studies. Further, in 43% of the studies, cognitive impairment was an exclusion criterion. In 47%, cognitive factors were not mentioned at all (Table 1). A few studies considered cognitive and other mental changes as natural ageing processes, that influenced the choice of administrative methods, such as reducing the number of questions posed (Hellstrom et al. 2004b; Tidermark et al. 2004), using a probing guide (Andersson et al. 2006) and training interviewers (Lee et al. 2006).

Discussion

The variability of the 47 evaluated studies was large related to the evidence provided for conceptual frameworks, definitions, measurements utilized, psychometric properties cited and methodological considerations given to the assessment of QoL among older adults.

Conceptual frameworks QoL

Of the 47 evaluated studies, 87% lacked evidence of a conceptual framework. Lund (2005) argues that when research is largely atheoretical, measurement validity is called into serious question, especially when the measure is not consistent with the conceptual definition. Gerritsen et al. (2004) suggested that a theoretical framework should: (1) be based on assumptions about the comprehensiveness of human beings in general; (2) describe the contribution of each domain to QoL, (3) identify relationships among dimensions, and (4) take individual preferences into account. In a recent review, Brown et al. (2004) found that researchers failed to address the complexity and dynamics of QoL and the interdependency of the domains, such as specifying distinctions between indicator and causal variables and potential mediating variables. They specifically advocated the need for causal models of ageing grounded in lay perspectives. Notably, in our review we found very few studies that specified causal interrelationships.

Evidence showed that both QoL and HRQoL remain ambiguous terms. Diffuse conceptual meanings were given to both terms, which were also reflected in their operationalization and measurement. For example, many studies referred to the same instruments as measurements for both terms, QoL and HRQoL. The words QoL and HRQoL were also used interchangeably in the same article. Various studies reported that HRQoL was measured, but described results as QoL (Fletcher et al. 2004; Kumar et al. 1995; MacRae et al. 1996; Pfisterer et al. 2003). These results support earlier reviews. Gill and Feinstein (1994) reported that QoL was used as a generic term for an assortment of physical and psychosocial variables, that few studies clarified the distinction between overall QoL and HRQoL, and that the majority of articles were atheoretical. Brown et al. (2004) also voiced concern, both theoretically and methodologically over the interchangeable use, without justification, of the term QoL with other related concepts, including HRQoL.

Definitions of QoL

Although a large majority of the studies imply that QoL and HRQoL is the major focus, only 43% of the studies specifically defined these concepts. QoL has been defined as a much broader concept than health, including cultural, political and social attributes such as quality of the environment, public safety, education, standard of living, transportation, political freedom or cultural amenities (Brown et al. 2004; Ferrans et al. 2005; Guyatt et al. 1996; Higgs et al. 2003). Others describe QoL as representing physical function, health status, perceptions, behavior, lifestyle, and social functioning (Frytak 2000; Moons 2004; O’Boyle 1997). Evidence from the review showed that HRQoL and QoL were measured by many of the same broad domains and content areas (Akifusa et al. 2005; Berkman 1999), a finding also supported by Brown et al (2004).

Quality of life measurements and domains

The most frequently applied measurements used, the SF-36 and the SF-12, represented the most comprehensive assessment when linked to Wilson and Cleary’s (1995) conceptual model. The Haywood et al. (2004) review of 40 instruments also found that the SF-36 was the most widely evaluated instrument. According to Wilson and Cleary’s (1995) model, the majority of measurements assessed functional status and symptoms, lending support to findings that QoL research in older adults have focused primarily on measures of health and illness as equivalents of QoL (Higgs et al. 2003). Few older adults-specific instruments were utilized, a finding supported by Brown et al (2004), in spite of the fact that the Haywood et al. (2004) review presented empirical evidence of 18 older adults-specific instruments. The need for the application and testing of existing older specific instruments needs to be addressed in future work.

Many of the additional domains and content areas assessed by 17 of the measurements, supported the findings of Brown et al.’s (2004) review regarding important domains nominated by older adults. The use of these additional measures suggests limitations found in existing instruments, supporting the need to focus on gaps in existing measurement scales. Haywood et al. (2004) found only one publication which evaluated limitations in domain coverage. Only two studies provided evidence for assessing lay views and personal importance given to various domains. Recently there have been more agreement about qualitative and quantitative assessment (Gilhooly et al. 2005), e.g., using open-ended questions for capturing lay views alongside standardized scales (Bowling et al. 2003). Our findings showed few studies using QoL and HRQoL measures together in older adults. Also Brown and colleagues (2004) found that few authors attempted to develop a composite model of QoL, showing QoL on a multi-dimensional continuum with different domains being analyzed together, rather than separately.

Psychometric properties

The SF-36 contained the greatest evidence base. The unacceptable internal consistency coefficients with Cronbach’s alpha cited in six of the reviewed studies, threaten the homogeneity of the items used, raising doubt as to what has actually been measured, and making it difficult to compare studies (Nunnally and Bernstein 1994; Streiner and Norman 2003). Responsiveness and acceptability were poorly reported. Only three studies cited ceiling and floor effects. Also, clinical significance of change scores were seldom reported, a finding supported by others (Deyo et al. 1991; Haywood et al. 2004, 2005b). These results may reflect problems in how to define change. Responsiveness of measures to change is especially important in studies of older adults, due to the controversy over whether dysfunction and diminished well-being can be reversed. Evidence for construct validity was reported for all measurements except one, with 16 measurements reporting convergent validity, 34 discriminate validity, and ten factor analysis.

Special considerations for the assessment of QoL among older adults

Of the studies, 55% did not provide any evidence of special content considerations given to the assessment of QoL amongst older adults. Almost half (47%) did not mention cognitive status. The Haywood et al. (2004) review found only two of 18 instruments assessing cognitive function. Future measurement of cognitive impairment demands special considerations (Ettema et al. 2005). More than half (55%) of the studies did not discuss any special considerations given to instrument adaptation among older adults. Administration difficulties, such as respondent burden, were seldom mentioned. Measurement of acceptability was found lacking for most instruments in another review (Andresen and Meyers 2000). Haywood et al. (2005b) specifically advised the seeking of views of older people with regard to instrument format, relevance and mode of completion. Future administration strategies could be considered, such as postal surveys with large print (Bowling et al. 2003; Hellstrom et al. 2004b; Pfisterer et al. 2003). Considerations should also be given to the educational level of older adults (Laake 2003). Most generic instruments, including the SF-36, which was utilized most frequently in the studies, are written at the seventh-grade reading level or higher (McHorney 1996).

Limitations

This review excluded 91% of the generated studies from the databases, mostly because the samples did not meet the age-specific criterion of 65 years of age or older. It can be questioned whether this criterion was too rigid, as it excluded larger studies recently conducted among older adults (Kempen et al. 1997, 1999; Power et al. 2005). Although a supplementary search was undertaken in social sciences and anthropological bases, limitations in our search method such as the exclusion of key terms meaning the same as QoL or being closely aligned with QoL, excluding grey literature, reports and systematic reviews, and not conducting manual searches in articles and books, can be cited for not providing a more relevant and comprehensive review of QoL measurement in old age (Bowling 2005; Bowling and Ebrahim 2005; Brown et al. 2004; Haywood et al. 2004; Walker 2005a; Walker 2005b; Walker 2005c) also possibly influencing the number of measurements which could represent level five of Wilson and Cleary’s (1995) model. Further, it has been shown that MeSH terms resulted in more precise searching and lower sensitivity than the search with text–word (Jenuwine and Floyd 2004). Jenuwine and Floyd (2004) reported relevant unique hits in each search strategy and recommended to use the combination of both strategies. Others have found that MeSH search provided a more efficient search than text word search (Chang et al. 2006). Nonetheless, researchers comparing MeSH searches in different bases, have found that the systems do not retrieve identical sets of documents (Gault et al. 2002; Hallett and Todd 1998). Because we used a keyword approach, the use of controlled vocabulary systems may have directly influenced system recall and precision capabilities in our searches. It may be considered a further limitation that we did not evaluate the adequacy of the empirical data reported, although this was not the aim of our paper. Our review brought our attention to the scarcity of an explicit grading systems which can be used in the interpretation, assessment and evaluation of the adequacy of evidence provided in publications (Andresen and Meyers 2000; Haywood et al. 2004).

Conclusion

Of the 47 studies reviewed, a great majority (87%) lacked a conceptual framework, and a third lacked any formal definition of QoL. Almost two-thirds of the studies focused on QoL, where HRQoL was used as an overlapping term. Although construct validity was reported in the majority of studies, minimal empirical evidence was provided for other psychometric properties of the instruments applied, a finding supported by others (Haywood et al. 2006). Furthermore, more than half of the studies did not report any methodological considerations given to older adults. Findings confirm the need for improvement in the quality of documented (reporting of) psychometric measurements so as to determine which of the growing number of QoL instruments perform most adequately and under what set of circumstances (Andresen and Meyers 2000; Brown et al. 2004; Grotle et al. 2005; Haywood et al. 2004, 2005b, 2006; McDowell and Jenkinson 1996; Terwee et al. 2007). Continued efforts are needed to reach interdisciplinary consensus on definitions of acceptable measurement standards for good measurement properties, including explicit quality criteria for the assessment and grading of these properties. Efforts are also needed to identify those content areas that are likely to discriminate best and display the greatest responsiveness to change. Our results lend support to Walker’s (2005b) discourse regarding the amorphous, multidimensional and complex nature of QoL and the need to resolve such methodological issues if interdisciplinary research on QoL is to develop further. Research grounded in subjective evaluations of QoL, are required to capture more adequately the multi-dimensional conceptualization reflected in measurement assessment. Future priority should be given to the development of common QoL assessment models that are person-centered, causal and multidimensional, based on collaborative efforts from professionals from the international gerontology research community.

References

Akifusa S, Soh I, Ansai T, Hamasaki T, Takata Y, Yohida A, Fukuhara M, Sonoki K, Takehara T (2005) Relationship of number of remaining teeth to health-related quality of life in community-dwelling elderly. Gerodontology 22(2):91–97

Altman DG (1999) Practical statistics for medical research. Chapman & Hall, London

Andersson M, Halberg IR, Edberg K (2006) The final period of life in elderly people in Sweden: factors associated with QoL. Int J Palliat Nurs 12(6):286–293

Andresen EM (2000) Criteria for assessing the tools of disability outcomes research. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 81(12 Suppl 2):15–20

Andresen EM, Meyers AR (2000) Health-related quality of life outcomes measures. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 81(2):30–45

Andrews F, Withey SB (eds) (1976) Social indicators of well-being: americans’ perceptions of life quality. Plenum, New York

Assantachai P, Maranetra N (2003) Nationwide survey of the health status and quality of life of elderly Thais attending clubs for the elderly. J Med Assoc Thai 86(10):938–946

Beaumont JG, Kenealy PM (2004) Quality of life perceptions and social comparisons in healthy old age. Ageing Soc 24(5):755–769

Berkman B (1999) Standardized screening of elderly patients’ needs for social work assessment in primary care: use of the SF-36. Health Soc Work 24(1):9–16

Berlowitz DR (1995) Health-related quality of life of nursing home residents: differences in patient and provider perceptions. J Am Geriatr Soc 43(7):799–802

Borders TF (2004) Factors associated with health-related quality of life among an older population in a largely rural western region. J Rural Health 20(1):67–75

Borglin G, Jakobsson U, Edberg AK, Hallberg IR (2005) Self-reported health complaints and their prediction of overall and health-related quality of life among elderly people. Int J Nurs Stud 42(2):147–158

Bowling A (2001a) Measuring disease: a review of disease specific quality of life measurement scales. 2nd edn., Open University Press, Philadelphia

Bowling A (2001b) Research methods in health: investigating health and health services. 2nd edn., University Press, Philadelphia

Bowling A (2005) Ageing well: quality of life in old age. Open University Press, Maidenhead

Bowling A, Banister D, Sutton S, Evans O, Windsor J (2002) A multidimensional model of the quality of life in older age. Aging Ment Health 6(4):355–371

Bowling A, Gabriel Z, Dykes J, Dowding LM, Evans O, Fleissig A, Banister D, Sutton S (2003) Let’s ask them: a national survey of definitions of quality of life and its enhancement among people aged 65 and over. Int J Aging Hum Dev 56(4):269–306

Bowling A, Ebrahim SS (eds) (2005) Handbook of health research methods: investigation, measurement and analysis. Open University Press, Maidenhead

Brand CA, Jones CT, Lowe AJ, Nielsen DA, Roberts CA, King BL, Campbell DA (2004) A transitional care service for elderly chronic disease patients at risk of readmission. Aust Health Rev 28(3):275–284

Brazier JE, Walters SJ, Nicholl JP, Kohler B (1996) Using the SF-36 and EuroQoL on an elderly population. Qual Life Res 5(2):195–204

Brown J, Bowling A, Flyn T (2004) Models of QoL: a taxonomy, overview and systematic review of the literature, European Forum on Population Ageing Research

Buck D, Jacoby A, Massey A, Ford G (2000) Evaluation of measures used to assess quality of life after stroke. Stroke 31(8):2004–2010

Burns R, Nichols LO, Martindale-Adams J, Graney MJ (2000) Interdisciplinary geriatric primary care evaluation and management: two-year outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc 48(1):8–13

Byles J (1999) Over the hill and picking up speed: older women of the Australian longitudinal study on women’s health. Aust J Ageing 18(3):55–62

Byles JE, Tavener M, O’Connell RL, Nair BR, Higginbotham NH, Jackson CL, McKernon ME, Francis L, Heller RF, Newbury JW, Marley JE, Goodger BG (2004) Randomised controlled trial of health assessments for older Australian veterans and war widows. Med J of Aust 181(4):186–190

Byles J, Young A, Furuya H, Parkinson L (2006) A drink to healthy aging: the association between older women’s use of alcohol and their health-related quality of life. J Am Geriatr Soc 54(9):1341–1347

Calman KC (1987) Definitions and dimensions of quality of life. In: Aaronson NK , Beckmann JH (eds) The quality of life of cancer patients. Raven, New York

Campbell A, Converse PE, Rodgers WJ (eds) (1976) The quality of American life: perceptions, evaluations, and satisfactions. Russell Sage, New York

Chang AA, Heskett KM, Davidson TM (2006) Searching the literature using medical subject headings versus text word with PubMed. Laryngoscope 116(2):336–340

Chinn PL, Kramer MK (eds) (1999) Theory and nursing: integrated knowledge development. Mosby, St Louis

Craig JV, Smyth RL (eds) (2002) The evidence-based practice manual for nurses. Churchill Livingstone, London

Cummins RA (1997) Assessing quality of life for people with disabilities. In: Brown R (ed) Quality of Life for people with disabilities: models, research and practice. 2nd edn., Stanley Thornes, Cheltenham, pp 116–150

De Korte J, Sprangers MAG, Mombers FMC, Bos JD (2004) Quality of life in patients with psoriasis: a systematic literature review. J Invest Dermatol Symp 9(2):140–147

De Leo D, Diekstra RF, Lonnqvist J, Trabucchi M, Cleiren MH, Frisoni GB, Dello BM, Haltunen A, Zucchetto M, Rozzini R, Grigoletto F, Sampaio-Faria J (1998) LEIPAD, an internationally applicable instrument to assess quality of life in the elderly. Behav Med 24(1):17–27

Dempster M, Donnelly M (2000) How well do elderly people complete individualised quality of life measures: an exploratory study. Qual Life Res 9(4):269–375

Deyo RA, Diehr P, Patrick DL (1991) Reproducibility and responsiveness of health status measures. Statistics and strategies for evaluation. Control Clin Trials 12(4 Suppl):142–158

Ellingson T, Conn VS (2000) Exercise and quality of life in elderly individuals. J Gerontol Nurs 26(3):17–25

Erikson EH, Erikson JM (eds) (1997) The life cycle completed. Norton, New York

Ettema TP, Droes RM, de Lange J, Mellenbergh GJ, Ribbe MW (2005) A review of quality of life instruments used in dementia. Qual Life Res 14(3):675–686

Farquhar M (1995) Elderly people’s definitions of quality of life. Soc Sci Med 41(10):1439–1446

Fayers PM, Machin D (eds) (2007) Quality of life: the assessment, analysis and interpretation of patient-reported outcomes. Wiley, Chichester

Feldman PH, Peng TR, Murtaugh CM, Kelleher C, Donelson SM, McCann ME, Putnam ME (2004) A randomized intervention to improve heart failure outcomes in community-based home health care. Home Health Care Serv Q 23(1):1–23

Ferrans CE, Zerwic JJ, Wilbur JE, Larson JL (2005) Conceptual model of health-related quality of life. J Nurs Scholar 37(4):336–342

Finkel SI, Richter EM, Clary CM (1999) Comparative efficacy and safety of sertraline versus nortriptyline in major depression in patients 70 and older. Int Psychogeriatr 11(1):85–99

Fitzpatrick R, Davey C, Buxton MJ, Jones DR (1998) Evaluating patient-based outcome measures for use in clinical trials. Health Technol Assess 2(14):1–74

Flanagan JC (1978) A research approach to improving our quality of life. Am Psychol 33(2):138–147

Fletcher AE, Dickinson EJ, Philp I (1992) Review: audit measures: quality of life instruments for everyday use with elderly patients. Age Ageing 21(2):142–150

Fletcher AE, Price GM, Ng ES, Stirling SL, Bulpitt CJ, Breeze E, Nunes M, Jones DA, Latif A, Fasey NM, Vickers MR, Tulloch AJ (2004) Population-based multidimensional assessment of older people in UK general practice: a cluster-randomised factorial trial. Lancet 364(9446):1667–1677

Fors S, Thorslund M, Parker MG (2006) Do actions speak louder than words? Self-assessed and performance-based measures of physical and visual function among old people. Eur J Ageing 3(1):15–21

Fries NJ (1983) Toward an understanding of patient outcome measurement. Arthritis Rheum 26(6):697

Fry PS (2001) Predictors of health-related quality of life perspectives, self-esteem, and life satisfactions of older adults following spousal loss: an 18-month follow-up study of widows and widowers. Gerontologist 41(6):787–798

Frytak JR (2000) Assessment of quality of life in older adults. In: Kane RL, Kane RA, Eells M. Assessing older persons: measures, meaning, and practical applications. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 200–236

Gagnon AJ, Schein C, McVey L, Bergman H (1999) Randomized controlled trial of nurse case management of frail older people. J Am Geriatr Soc 47(9):1118–1124

Gault LV, Shultz M, Davies K (2002) Variations in medical subject headings (MeSH) mapping: from the natural language of patron terms to the controlled vocabulary of mapped lists. J Med Libr Assoc 90(2):173–180

George LK, Bearon LB (eds) (1980) Quality of life in older persons: meaning and measurement. Human Sciences Press, New York

Gerritsen DL, Steverink N, Ooms ME, Ribbe MW (2004) Finding a useful conceptual basis for enhancing the quality of life of nursing home residents. Qual Life Res 13(3):611–624

Gilhooly M, Gilhooly K, Bowling A (2005) Quality of life measuring and measurement. In: Walker A (ed) Understanding quality of life in old age. Open University Press, Maidenhead, pp 14–26

Gill TM, Feinstein AR (1994) A critical appraisal of the quality of quality-of-life measurements. JAMA 272(8):619–626

Grimby A, Wiklund I (1994) Health-related quality of life in old age. A study among 76-year-old Swedish urban citizens. Scand J Soc Med 22(1):7–14

Grotle M, Brox JI, Vollestad NK (2005) Functional status and disability questionnaires: what do they assess? A systematic review of back-specific outcome questionnaires. Spine 30(1):130–140

Grundy EE (2006) Ageing and vulnerable elderly people: European perspectives. Ageing Soc 26(1):105–134

Grundy E, Bowling A (1999) Enhancing the quality of extended life years. Identification of the oldest old with a very good and very poor quality of life. Aging Ment Health 3(3):199–212

Guyatt GH, Jaeschke F, Patrick D (1996) Measurement in clinical trials: choosing the right approach. In: Spilker B (ed) Quality of life and pharmacoeconomics in clinical trials. 2 edn., Lippincott-Raven, Philadelphia

Hallett KS, Todd AL (1998) Separate but equal? A system comparison study of Medline’s controlled vocabulary MeSH. Bull Med Libr Assoc 86(4):491–495

Hanlon JT, Weinberger M, Samsa GP, Schmader KE, Uttech KM, Lewis IK, Cowper PA, Landsman PB, Cohen HJ, Feussner JR (1996) A randomized, controlled trial of a clinical pharmacist intervention to improve inappropriate prescribing in elderly outpatients with polypharmacy. Am J Med 100(4):428–437

Haywood KL, Garratt AM, Schmidt LJ, Mackintosh A, Fitzpatrick R (2004) Health status and quality of life in older people: a review, National Centre for Health Outcomes Development, Oxford

Haywood KL, Garratt AM, Fitzpatrick R (2005a) Older people specific health status and quality of life: a structured review of self-assessed instruments. J Eval Clin Pract 11(4):315–327

Haywood KL, Garratt AM, Fitzpatrick R (2005b) Quality of life in older people: a structured review of generic self-assessed health instruments. Qual Life Res 14(7):1651–1668

Haywood KL, Garratt AM, Fitzpatrick R (2006) Quality of life in older people: a structured review of self-assessed health instruments. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcom Res 2(6):181–194

Hellstrom Y, Andersson M, Hallberg IR (2004a) Quality of life among older people in Sweden receiving help from informal and/or formal helpers at home or in special accommodation. Health Soc Care Community 12(6):504–516

Hellstrom Y, Persson G, Hallberg IR (2004b) Quality of life and symptoms among older people living at home. J Adv Nurs 48(6):584–593

Hendry F, McVittie C (2004) Is quality of life a healthy concept? Measuring and understanding life experiences of older people. Qual Health Res 14(7):961–975

Higgs P, Hyde M, Wiggins R, Blane B (2003) Researching quality of life in early old age the importance of the sociological dimension. Soc Policy Adm 37(3):239–252

Hughes C, Hwang B (1996) Attempts to conceptualize and measure quality of life. In: Schalock RL (ed) Quality of life, vol 1. Conceptualization and measurement. American Association on Mental Retardation, Washington, pp 51–62

Hyland ME (1992) A reformulation of quality of life for medical science. Qual Life Res 1(4):267–272

Jenkins KR (2002) Activity and health-related quality of life in continuing care retirement communities. Res Aging 24(1):124–149

Jenuwine ES, Floyd JA (2004) Comparison of medical subject headings and text–word searches in MEDLINE to retrieve studies on sleep in healthy individuals. J Med Libr Assoc 92(3):349–353

Kane RL, Kane RA, Eells M (2002) Assessing older persons: measures, meaning, and practical applications. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Kempen GI, Ormel J, Brilman EI, Relyveld J (1997) Adaptive responses among Dutch elderly: the impact of eight chronic medical conditions on health-related quality of life. Am J Public Health 87(1):38–44

Kempen GI, Brilman EI, Ranchor AV, Ormel J (1999) Morbidity and quality of life and the moderating effects of level of education in the elderly. Soc Sci Med 49(1):143–149

Krause N (2004) Lifetime trauma, emotional support, and life satisfaction among older adults. Gerontologist 44(5):615–623

Kumar P, Zehr KJ, Chang A, Cameron DE, Baumgartner WA (1995) Quality of life in octogenarians after open heart surgery. Chest 108(4):919–926

Laake K (2003) Geriatri i praksis (Geriatrics in practice). 4th edn., Gyldendal Akademisk, Oslo

Lee TW, Ko IS, Lee KJ (2006) Health promotion behaviours and quality of life among community-dwelling elderly in Korea: a cross-sectional survey. Int J Nurs Stud 43(3):293–300

Liu-Ambrose TY, Khan KM, Eng JJ, Lord SR, Lentle B, McKay HA (2005) Both resistance and agility training reduce back pain and improve health-related quality of life in older women with low bone mass. Osteoporos Int 16(11):1321–1329

Livingston G, Watkin V, Manela M, Rosser R, Katona C (1998) Quality of life in older people. Aging Ment Health 2(1):20–23

MacRae PG, Asplund LA, Schnelle JF, Ouslander JG, Abrahamse A, Morris C (1996) A walking program for nursing home residents: effects on walk endurance, physical activity, mobility, and quality of life. J Am Geriatr Soc 44(2):175–180

Maslow AH (1954) Motivation and personality. Harper and Row, New York

McDowell I, Jenkinson C (1996) Development standards for health measures. J Health Serv Res Policy 1(4):238–246

McFall SL (2000) Outcomes of a small group educational intervention for urinary incontinence: health-related quality of life. J Aging Health 12(3):301–317

McHorney CA (1996) Measuring and monitoring general health status in elderly persons: practical and methodological issues in using the SF-36 Health Survey. Gerontologist 36(5):571–583

McHugh GJ, Havill JH, Armistead SH, Ullal RR, Fayers TM (1997) Follow up of elderly patients after cardiac surgery and intensive care unit admission, 1991 to 1995. N Z Med J 110(1056):432–435

Moons P (2004) Why call it health-related quality of life when you mean perceived health status? Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 3(4):275–277

Nelson ME, Layne JE, Bernstein MJ, Nuernberger A, Castaneda C, Kaliton D, Hausdorff J, Judge JO, Buchner DM, Roubenoff R, Fiatarone Singh MA (2004) The effects of multidimensional home-based exercise on functional performance in elderly people. J Gerontol Biol Sci Med Sci 59(2):154–160

Nesbitt BJ, Heidrich SM (2000) Sense of coherence and illness appraisal in older women’s quality of life. Res Nurs Health 23(1):25–34

Nilsson M, Ekman S, Sarvimaki A (1998) Ageing with joy or resigning to old age: older people’s experiences of the quality of life in old age. Health Care Later Life 3(2):94–110

Noro A, Aro S (1996) Health-related quality of life among the least dependent institutional elderly compared with the non-institutional elderly population. Qual Life Res 5(3):355–366

Nunnally J, Bernstein IH (eds) (1994) Psychometric theory. 3rd edn., McGraw-Hill, New York

O’Boyle CA (1997) Measuring the quality of later life. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 352(1363):1871–1879

Østby L (2004) Den norske eldrebølgen: ikke blant Europas største, men dyrt kan det bli (The Norwegian old age wave: not the largest in Europe, but potentially expensive). Samfunnspeilet 18(1):2–8

Parse RR (2003) The lived experience of feeling very tired: a study using the Parse research method. Nurs Sci Q 16(4):319–325

Patrick DL, Chiang YP (2000) Measurement of health outcomes in treatment effectiveness evaluations: conceptual and methodological challenges. Med Care 38(9 Suppl):14–25

Peek MK (2004) Reliability and validity of the SF-36 among older Mexican Americans. Gerontologist 44(3):418

Pfisterer M, Buser P, Osswald S, Allemann U, Amann W, Angehrn W, Eeckhout E, Erne P, Estlinbaum W, Kuster G, Moccetti T, Naegeli B, Rickenbacher P, Trial of Invasive versus Medical therapy in Elderly patients (TIME) Investigators (2003) Outcome of elderly patients with chronic symptomatic coronary artery disease with an invasive vs optimized medical treatment strategy: one-year results of the randomized TIME trial. JAMA 289(9):1117–1123

Polit D, Beck C (eds) (2004) Nursing research: principles and methods. 7th edn, Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia

Power M, Bullinger M, Harper A (1999) The World Health Organization WHOQoL-100: tests of the universality of quality of life in 15 different cultural groups worldwide. Health Psychol 18(5):495–505

Power M, Quinn K, Schmidt S (2005) Development of the WHOQoL-old module. Qual Life Res 14(10):2197–2214

Reeves BC, Harper RA, Russell WB (2004) Enhanced low vision rehabilitation for people with age related macular degeneration: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Ophthalmol 88(11):1443–1449

Repetto L, Comandini D, Mammoliti S (2001) Life expectancy, comorbidity and quality of life: the treatment equation in the older cancer patients. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 37(2):147–152

Rodriguez-Manas L, Guillen F, Caballero JC, Tobares N, Sempere R (1996) A comparison of the efficacy, tolerability and effect on quality of life of nisoldipine CC and enalapril in elderly patients with mild-to-moderate hypertension. Acta Ther 22(2–4):89–106

Sarvimaki A, Stenbock-Hult B (2000) Quality of life in old age described as a sense of well-being, meaning and value. J Adv Nurs 32(4):1025–1033

Scientific Advisory Committee of the Medical Outcomes Trust (2002) Assessing health status and quality-of-life instruments: attributes and review criteria. Qual Life Res 11(3):193–205

Sirgy MJ, Michalos AC, Ferriss AL, Easterlin RA, Pavot W, Patrick D (2006) The quality-of-life (QoL) research movement: past, present, and future. Soc Indic Res 76(3):343–366

Stenzelius K, Westergren A, Thorneman G, Hallberg IR (2005) Patterns of health complaints among people 75+ in relation to quality of life and need of help. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 40(1):85–102

Streiner DL, Norman GR (eds) (2003) Health measurement scales: a practical guide to their development and use. 3rd edn., Oxford University Press, Oxford

Streiner DL, Norman GR (2006) “Precision” and “accuracy”: two terms that are neither. J Clin Epidemiol 59(4):327–330

Taylor SJ, Bogdan R (1990) Quality of life and the individual’s perspective. In: Schalock R, Begab MJ (eds) Quality of life: perspectives and issues. American Asscoiation on Mental Retardation, Washington, pp 27–40

Terwee CB, Dekker FW, Wiersinga WM, Prummel MF, Bossuyt PM (2003) On assessing responsiveness of health-related quality of life instruments: guidelines for instrument evaluation. Qual Life Res 12(4):349–362

Terwee CB, Bot SDM, de Boer MR, van der Windt DAWM, Knol DL, Dekker J, Bouter LM, de Vet HCW (2007) Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol 60(1):34–42

Tidermark J, Ponzer S, Carlsson P, Soderqvist A, Brismar K, Tengstrand B, Cederholm T (2004) Effects of protein-rich supplementation and nandrolone in lean elderly women with femoral neck fractures. Clin Nutr 23(4):587–596

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration, Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH) (2006) Guidance for industry patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims. Health and quality of life outcome

Varma S, McElnay JC, Hughes CM, Passmore AP, Varma M (1999) Pharmaceutical care of patients with congestive heart failure: interventions and outcomes. Pharmacotherapy 19(7):860–869

Walker A (2005a) Growing older in Europe. Open University Press, Maidenhead

Walker A (2005b) Understanding quality of life in old age. Open University Press, Maidenhead

Walker A (2005c) A European perspective on quality of life in old age. Eur J Ageing 2(1):12

White F (1967) Improved medical care statistics and the health services system. Public Health Rep 82(10):847

Wilson IB, Cleary PD (1995) Linking clinical variables with health-related quality of life. A conceptual model of patient outcomes. JAMA 273(1):59–65

World health Organization (2000) Social development and ageing: crisis or opportunity? Geneva

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the financial support from Diakonova University College, Department of Nursing Research. We want to express our gratitude to Librarian Jenny Owe, Diakonova University College, for library assistance and the EJA’s anonymous referees.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Halvorsrud, L., Kalfoss, M. The conceptualization and measurement of quality of life in older adults: a review of empirical studies published during 1994–2006. Eur J Ageing 4, 229–246 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-007-0063-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-007-0063-3