Abstract

Forest fragmentation and agricultural development are important anthropogenic landscape alterations affecting the disease dynamics of malarial parasites (Plasmodium spp.), largely through their effects on vector communities. We compared vector abundance and species composition at two forest edge sites abutting pastureland and two forest interior sites in New Zealand, while simultaneously assessing avian malaria prevalence in silvereyes (Zosterops lateralis). Twenty-two of 240 (9.2%) individual silvereyes captured across all sites tested positive for avian malaria, and Plasmodium prevalence was nearly identical in edge and interior habitats. A total of 580 mosquito specimens were trapped across all sites. These comprised five different species: the introduced Aedes notoscriptus and Culex quinquefasciatus; the native A. antipodeus, C. asteliae and C. pervigilans. The known avian malaria vector C. quinquefasciatus was only recorded in the forest edge (mostly at ground level). In contrast, the probable vector C. pervigilans was abundant and widespread in both edge and interior sites. Although frequently caught in ground traps, more C. pervigilans specimens were captured in the canopy. This study shows that avian malaria prevalence among silvereyes appeared to be unaffected by forest fragmentation, at least at the scale assessed. Introduced mosquito species were almost completely absent from the forest interior, and thus our study provides further circumstantial evidence that native mosquito species (in particular C. pervigilans) play an important role in avian malaria transmission in New Zealand.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Human land-use changes are altering the disease dynamics of malarial parasites (Plasmodium spp.), primarily through their effect on vector species (Patz et al. 2000; Harvell et al. 2002). In many parts of the world, deforestation for agricultural development is a common anthropogenic driver of changes in parasite transmission rates (Yasuoka and Levins 2007; Sehgal 2010; LaPointe et al. 2012). Studies of human malaria in Asia, Africa and the Amazon region have shown that forest fragmentation and increasing edge habitat produce complex host-vector responses; these can either increase or decrease malaria prevalence depending on subsequent land use and the breeding ecology of local vector species (see Yasuoka and Levins 2007, Stefani et al. 2013).

Similar results have been demonstrated for avian malaria, with deforestation producing variable prevalence patterns at both local and regional scales (see Sehgal 2010, LaPointe et al. 2012). For example, recent studies in Africa by Bonneaud et al. (2009) and Loiseau et al. (2010) found higher Plasmodium prevalence in birds inhabiting pristine forests, whereas Chasar et al. (2009) revealed one parasite species was more abundant in disturbed sites and another more so in pristine sites. Ribeiro et al. (2005) found higher prevalence rates in large versus small forest fragments in Brazil, while Laurance et al. (2013) found no difference in prevalence rates between continuous forest and smaller fragments in Australia. The aforementioned authors and Sehgal (2010) suggested vector abundance and species composition, breeding ecology and specificity for certain Plasmodium lineages are likely driving prevalence differences. Unfortunately, few authors have included mosquito sampling in their research protocols, and the vector competence of many species remains unknown (Valkiunas 2005).

In Hawaii, the introduction of an exotic efficient vector (Culex quinquefasciatus) and virulent malarial parasite (Plasmodium relictum) led to an epidemic that devastated native bird populations in the 20th century (van Riper III et al. 1986), and still persists today (Freed and Cann 2013). Since their introductions, forest fragmentation and agricultural development have been implicated in increasing avian malaria transmission (LaPointe et al. 2012). As an open-container breeder and a peridomestic species, C. quinquefasciatus greatly benefits from the clearing of forest for human land uses (Reiter and LaPointe 2007). The resultant increase in larval habitat and access to naïve hosts may be perpetuating parasite transmission to birds inhabiting forested conservation areas (Lapointe 2008). However, this model is likely not applicable to continental ecosystems due to the introduced vector-parasite and naïve host system, and the Hawaiian situation is unique in that there were no blood-sucking insects prior to the accidental introduction of mosquitoes by humans (Waldbauer 2012). Nonetheless, there is a concern that other island ecosystems with high numbers of endemic birds (most notably New Zealand and the Galapagos) could be similarly affected by the interaction of exotic mosquitoes, anthropogenic environmental change and avian malaria (Derraik and Slaney 2007; LaPointe et al. 2012).

In New Zealand, much of the original forest cover has become increasingly fragmented by agriculture since human settlement, particularly on the North Island (Ewers et al. 2006). Culex quinquefasciatus is already present on the North Island (having been introduced in the 1800s), where it is currently restricted in distribution probably due to climactic factors (Derraik and Slaney 2007). Multiple lineages of avian malaria have also been in the country since at least the mid-1900s when the genus Plasmodium was first isolated by Laird (1950), and several cases of mortality have been documented among threatened birds in captivity (Derraik et al. 2008; Schoener et al. 2014). However, over the last decade increased sampling effort and the application of molecular tools have improved our understanding of avian malaria in New Zealand, and a number of previously unknown Plasmodium and host species associations have been identified; to date 17 lineages of Plasmodium have been isolated from 35 bird species (Baillie and Brunton 2011; Schoener et al. 2014). Additionally, Ewen et al. (2012) found that the New Zealand Plasmodium fauna comprises introduced parasites as well as two presumed endemic species that predate human colonization and the introduction of exotic avian hosts.

Even so, some concern still remains that the arrival and spread of highly competent exotic vectors such as C. quinquefasciatus will lead to increased opportunity for malarial parasite transmission in New Zealand. This could negatively affect native and endemic bird species through increased parasite loads at the individual and population levels, as well as eventually facilitating the evolution of more virulent strains. Despite this, we do not know of any New Zealand study investigating the potential anthropogenic drivers of Plasmodium transmission. Thus, we aimed to assess the vector communities and avian malaria prevalence in a ubiquitous native bird (silvereye, Zosterops lateralis) at forest edge and interior habitats in a regional park in New Zealand.

Methods

Ethics

Ethics approval was provided by the Massey University Animal Ethics Committee (AEC/13, amended 01/09) and the New Zealand Department of Conservation (permit AK-20666-FAU). Bird banding was carried out under Department of Conservation permit no. 2008/33.

Study Design

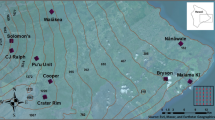

This study was carried out in February–April 2010 (summer–autumn) at Waharau Regional Park (37°02′95′′S, 175°17′98′′E) on the North Island of New Zealand (Figure 1). The park consists of podocarp-broadleaf forest along the eastern foothills of the Hunua Ranges and sheep-grazing pastureland at lower elevations near the Firth of Thames. The forested area becomes increasingly bottlenecked near sea level, with pastureland surrounding the eastern and western borders of the park.

Two forest edge (E1/E2) and two forest interior (I1/I2) sites were selected for sampling (Figure 1). Sites were randomly chosen within a given set of criteria: (i) edge sites were less than 50 m from the forest-pastureland boundary; (ii) interior sites were at least 500 m away from any forest edge; (iii) all sites were at least 500 m apart; and (iv) all sites had to be relatively near a walking track. The first criterion was based on Young and Mitchell (1994), who found strong microclimatic and structural vegetation differences up to 50 m from the edge in a New Zealand podocarp-broadleaf forest. The second and third criteria were set to minimise potential host and vector movements between sites, with the 500 m distance reflecting a compromise between park boundaries and logistical feasibility of sampling. The latter factor was also the main basis for the fourth criterion.

Both edge sites (120–150 m a.s.l.) abutted pastureland and were dominated by celery pine (Phyllocladus glaucus), kanuka (Kunzea ericoides) and manuka (Leptospermum scoparium). The interior sites (180–270 m a.s.l.) consisted of the aforementioned species mixed with large, mature kauri (Agathis australis), totara (Podocarpus totara), tawa (Beilschmiedia tawa), rimu (Dacrydium cupressinum) and puriri (Vitex lucens) trees. The park has a number of streams running through it (a potential source of bias for the mosquito sampling), but nearest stream distance was similar across sites (18–31 m).

Each individual sampling site consisted of a 50 m × 100 m grid (Figure 1). Data loggers (Hobo Pro, Onset Computer Corp., Pocasset, MA, USA) were placed at each site during vector sampling to monitor potential differences in relative humidity and temperature, which are known to affect mosquito abundance (Martens et al. 1999).

Mosquito Sampling

We conducted adult mosquito sampling in late summer (February–March), when abundance and biting activity in the Auckland region appear to be highest (Derraik and Slaney 2005). Mosquitoes were captured using All-Weather Encephalitis Vector Survey light traps (Bioquip Products, Rancho Dominguez, CA, USA) baited with dry ice (CO2). This type of trap was chosen for its relatively high capture efficiency across a wide range of mosquito species (Silver 2008), and similar CO2-light traps have been successfully used in previous studies on mosquitoes in New Zealand (e.g. Derraik et al. 2005a, b; Derraik 2009a). Since most of the mosquito species present in the North Island of New Zealand appear to be crepuscular and/or nocturnal feeders (Derraik et al. 2005a), the traps were set approximately 2 h before sunset (~19:00) and emptied approximately 2 h after sunrise (~07:00) for a total of 12 trapping hours per sampling bout. Only female mosquitoes were kept for identification and analyses. Captured specimens were placed in a container with tissue paper and refrigerated until being transported to the laboratory. They were then identified to species under a dissecting microscope, with the aid of a taxonomic key (Snell 2005).

There were two mosquito species of primary interest. The introduced C. quinquefasciatus is an efficient vector of avian malaria responsible for extensive impacts on Hawaii’s endemic bird fauna (van Riper III et al. 1986), and whose distribution has been correlated with that of avian malaria in New Zealand (Tompkins and Gleeson 2006). In addition, the native C. pervigilans is most likely an avian malaria vector in New Zealand, being for example the only culicid species recorded in areas where previous outbreaks have occurred (Derraik et al. 2008).

Mosquito sampling of edge and interior sites was paired and carried out simultaneously to control for possible temporal variations in relative abundance. E1 and I1 were sampled in 20–27 February and E2 and I2 were sampled from 1–9 March. For sampling, two traps were placed on a single tree, one at ground level (~1.5 m) and one in the canopy (~10 m). This was done on two trees, which were separated by at least 20 m to prevent over-sampling a small area within each site, for a total of four traps per site (Figure 1). Half of the traps from the second sampling bout (four from E2 and four from I2) were sampled an additional day (9th March) to make use of all available dry ice. This resulted in a total of 120 mosquito traps set over the course of the study. Ground and canopy trap placements were done to discern vertical distribution patterns for each species, which may be related to feeding patterns and host preference (Derraik et al. 2005b).

Avian Sampling

We targeted the native silvereye (Zosterops lateralis) due to its high relative abundance and ubiquitous distribution in New Zealand (where it inhabits urban areas, forests and many offshore islands) (Diamond 1984), as well as its confirmed status as a host of avian malaria here (Howe et al. 2012). Sampling was conducted in March–April (late summer–early autumn). Birds were mist-netted from early morning (~08:00) to dusk (~18:00). Playback recordings were used to maximise capture rates. Upon capture, each bird was placed in a cloth bag, weighed, and then banded to prevent re-sampling.

A thin blood smear was prepared using a small blood sample (~20 μl) extracted from the brachial vein, which was then air-dried and fixed with absolute methanol. The fixed smear was stained by immersion in Giemsa solution at a 1:10 dilution with double-distilled water for 1 h. The stained smears were examined with a light microscope under oil-immersion at 1000× magnification for approximately 30 min. Parasites were identified based on morphospecies descriptions in Valkiunas (2005) when possible. Prevalence was calculated as the proportion of infected individuals to the total number sampled and expressed as a percentage. Bird sampling was rotated between sites every two weeks (from Edge 1 to Interior 1, then Edge 2 to Interior 2).

Statistical Analyses

Avian malaria prevalence in edge and interior sites was compared using a two-sample Poisson rate test, while microclimatic data were compared using paired t tests (Minitab v.16, Pennsylvania State University, State College, PA, USA). Mosquito abundance data were assessed using generalised linear mixed models based on a Poisson distribution, with trap and date set as random factors. Trap catches were compared between edge and interior habitats, as well as between ground and canopy traps. Binary logistic regressions based on similar models were also run to compare trap-occupancy rates. Multivariate models were carried out in SAS v.9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). All statistical tests were two-tailed and significance level maintained at 5%.

Results

Avian Malaria Prevalence

Similar numbers of silvereyes were captured in edge and interior sites (Table 1). A total of 22 of the 240 (9.2%) individual silvereyes captured across all sites tested positive for avian malaria infection (Table 1). The majority of infected birds (n = 20) harboured parasites consistent with Plasmodium (Huffia) elongatum, with the remaining two harbouring parasites consistent with Plasmodium (Haemamoeba) relictum (Table 1). Plasmodium prevalence was nearly identical in edge (9.5%) and interior habitats (8.9%; P = 0.88) (Table 1). Eleven birds were recaptured throughout the course of the study, all within the same site in which they were initially sampled.

Mosquito Fauna

A total of 580 female mosquitoes comprising five different species were trapped across all sites: the introduced Aedes notoscriptus and C. quinquefasciatus; the native A. antipodeus, C. asteliae and C. pervigilans. Native mosquitoes far outnumbered introduced species in total captures across all sites (Table 2). Notably, exotic mosquitoes were almost entirely absent from the forest interior traps, where only one A. notoscriptus specimen was captured (Table 2).

Avian Malaria Vectors

Culex quinquefasciatus was only recorded in the forest edge, being apparently absent from interior sites (Table 2). All but two of the 18 specimens recorded were captured in ground traps (Table 3).

The native C. pervigilans was the most abundant species recorded at the forest edge, being also relatively common and abundant in interior sites (Table 1). It was also the most widespread species, being captured in 78 of the 120 traps set (65%; Table 2). Although frequently caught at both trap heights, more specimens were captured in the canopy (Table 3).

Other Culicids

Aedes notoscriptus was the most abundant introduced species recorded, which, as previously stated, were nearly absent from interior sites (Table 2). The species displayed no preference for forest strata, being similarly recorded in ground and canopy traps (Table 3).

The native A. antipodeus was the most abundant species recorded overall (280 specimens), showing a preference for the forest interior (Table 2). Aedes antipodeus displayed a marked vertical stratification, with 96% of specimens recorded in ground traps (Table 3). In contrast, the native C. asteliae showed the opposite pattern, being more abundant and more frequently recorded in canopy traps (Table 3). Culex asteliae displayed no preference for interior or edge sites (Table 2).

Microclimate

There was no difference in the average daily temperature between the edge and interior sites (18.8 vs. 18.5°C; P = 0.16). Yet, the average daily relative humidity was 2.5% higher in interior (78.4%) than in edge habitats (75.9%; P = 0.009). However, neither variable was correlated with relative abundance of mosquitoes.

Discussion

The overall prevalence of avian malaria (P. elongatum and P. relictum) in silvereyes was low (9.2%). Although our exclusive use of microscopy for parasite detection might have led to an underestimation of prevalence (Valkiunas et al. 2008), we attempted to minimize this by thoroughly examining each slide as per Garamszegi (2010). More importantly, we found prevalence to be nearly identical in forest edge and interior habitats using the same survey effort across all study slides. While these findings differ from some continental studies (e.g. Wood et al. 2007; Bonneaud et al. 2009; Chasar et al. 2009; Loiseau et al. 2010), they are consistent with a recent Australian study that found no differences in Plasmodium prevalence across a range of avian species in forest edge and interior habitats (Laurance et al. 2013). It was also interesting to note that the globally widespread P. elongatum was by far the most common malaria parasite encountered in silvereyes in this study (n = 20). This finding is in accordance with previous studies in New Zealand, which have demonstrated the presence of P. elongatum in a wide range of native species and its ubiquitous distribution throughout the country (Baillie and Brunton 2011; Castro et al. 2011; Ewen et al. 2012; Howe et al. 2012).

There were two possible sources of bias for our prevalence results. First, if individual silvereyes were moving between the edge and interior sites, this could explain the similar malaria prevalence in the two habitat types. Second, we cannot exclude the possibility that birds were being infected while roosting in a different area from which they were captured. However, silvereye home ranges averaged less than 300 m for the majority of individuals on Heron Island (Australia) (Catterall et al. 1989), and resident silvereyes rarely move at night during the breeding season (Chan 1995; Funnell and Munro 2010). In addition, all eleven of our recaptures occurred within-site in Waharau. Therefore, it is unlikely that there was significant movement of individuals between sites, and our findings likely reflect a similar prevalence of avian malaria in both habitat areas. Larger-scale studies are required to confirm these results.

For New Zealand’s native avifauna, anthropogenic environmental changes not only result in decreased availability of suitable forest habitats and increased exposure to introduced mammalian predators, but also potentially open a malarial transmission pathway through increased vulnerability to efficient malaria vectors (e.g. C. quinquefasciatus) and higher densities of often-infected exotic avian hosts (LaPointe et al. 2012). Indeed, Ewen et al. (2012) suggested that the transmission of introduced malaria parasites may be driven by the extent of habitat overlap between native and introduced bird species in New Zealand. Our data offer some support for these scenarios. In Waharau for example, four exotic birds caught during this study all tested positive for avian malaria, with a song thrush (Turdus philomelos) harbouring P. elongatum and three blackbirds (Turdus merula) exhibiting heavy mixed infections of P. relictum and P. vaughani (D. Gudex-Cross, unpublished data). Blackbirds and song thrushes are two of the most widely distributed introduced species within New Zealand, both being found throughout forest habitats and adjacent disturbed areas (Robertson et al. 2007). Interestingly, all three blackbirds were captured at the same edge site (E2) where one of the two silvereyes carrying P. relictum was also found. Thereby, as per the suggestion by Ewen et al. (2012), the low prevalence of P. relictum in silvereyes in this study may be due to limited overlap with areas of high blackbird numbers, outside the forest edge. In contrast, the second silvereye carrying P. relictum was captured at an interior site (I2). Although an interior-forest exotic bird infected with P. relictum was not detected in this survey, the song thrush and blackbird both represent possible candidates. Further, the song thrush carrying P. elongatum was caught at an interior site (F1), suggesting that this species may play a role in the transmission of P. elongatum inside New Zealand forests. These prevalence data provide further evidence that exotic reservoir hosts are likely facilitating avian malaria transmission in New Zealand’s native forests. It is also worth noting that, although the silvereye is classified as a native species, it is believed to be a relatively new self-introduction to New Zealand (ca. mid-1800s) (Mees 1969; Estoup and Clegg 2003). Thus, in host-parasite evolutionary terms, the role of the silvereye in the endemic avian malaria transmission cycle in New Zealand remains largely unknown.

Average daily temperature and relative humidity did not explain the differences in mosquito species abundance in our study, and thus can be ruled out as factors driving the compositional differences between the forest edge and interior. Although the avian malaria vector C. quinquefasciatus was only recorded in the forest edge, C. pervigilans was abundant across all study sites, providing further circumstantial evidence that C. pervigilans plays an important role in avian malaria transmission in New Zealand (see Massey et al. 2007; Derraik et al. 2008). The species’ greater relative abundance in canopy traps indicates that it likely takes blood meals from roosting birds. Thus, its ubiquitous distribution in Waharau and similar abundance at each site provides the most plausible explanation for the observed malaria prevalence data in silvereyes. It is interesting to note that the likely association between P. elongatum and C. pervigilans here, which also highlights the importance of carrying out further work to determine the vector competence of this mosquito species for different lineages of avian malaria in New Zealand.

Our results corroborate previous findings showing that forest fragmentation in the Auckland region favours introduced mosquito species, which were nearly absent from large tracts of native forest (Derraik et al. 2005a; Derraik 2009a). Given both C. quinquefasciatus and A. notoscriptus are vectors of human and animal disease (Derraik 2004), this study adds further evidence that anthropogenic environmental change is associated with an increased transmission risk of vector-borne diseases, particularly in the more densely populated Auckland region.

From a human health perspective, this species replacement in New Zealand means that a primarily bird-feeding native mosquito fauna is being replaced by an anthropophilic or opportunistic introduced mosquito fauna of known disease vectors (Derraik and Slaney 2007). To date, there has never been a confirmed indigenously acquired case of mosquito-borne disease in humans in New Zealand (Derraik and Maguire 2005). However, arboviruses such as Ross River virus, Chikungunya virus and Zika virus are present in Australia or the South Pacific, and pose an increasing threat to human health in New Zealand (Derraik and Slaney 2007, 2015; Derraik et al. 2010). In particular, A. notoscriptus is abundant and widespread in northern New Zealand (thriving in human-modified environments, including urban areas) (Derraik and Slaney 2007), and could play an important role in disease transmission to humans as a potential vector of these viruses (Derraik and Slaney 2007, 2015; Derraik et al. 2010).

The ecological findings of this study also support data from previous work on mosquitoes in the Auckland region, as A. antipodeus was also the most abundant native species recorded in other tracts of native forest (Derraik et al. 2005b; Derraik 2009a). This species breeds in temporary ground pools in areas with partial or dense shade (Belkin 1968), and our results and previous findings (Derraik et al. 2005a; Derraik 2009a) suggest that relatively pristine mature forests provide greater availability of suitable larval habitats.

Neither of the other two native species caught in this study (C. asteliae and C. pervigilans) showed any preference for edge or interior sites. This is not surprising for C. pervigilans, which is New Zealand’s most abundant and widespread mosquito species, occupying a remarkably wide range of larval habitats (Belkin 1968; Derraik 2005). Culex asteliae breeds primarily within the leaf axils of the native epiphyte Collospermum hastatum (Derraik 2009b), but it has also been recorded in bromeliads in anthropic habitats (Derraik 2005). Thus, this species would likely occur near native forests if suitable larval habitats are available (Derraik 2005). Although larvae of C. asteliae are often found at ground level (Derraik 2009b), its preference for foraging at canopy level is in accordance with previous work (Derraik et al. 2005b). The greater abundance of C. asteliae and C. pervigilans in the canopy reflects their likely avian host specificity given New Zealand’s historic lack of land mammals (Derraik et al. 2005b). Yet, the competence of C. asteliae as an avian malaria vector is unknown and requires investigation, particularly since it is closely related to C. pervigilans (Belkin 1968).

In conclusion, this study shows that avian malaria prevalence among silvereyes appeared to be unaffected by forest fragmentation in the Waharau Regional Park. However, these findings need to be corroborated in larger studies. Nevertheless, our study provides further circumstantial evidence that native mosquitoes (in particular C. pervigilans) most likely play an important role in avian malaria transmission in New Zealand. There has been limited work done on the vector competence of New Zealand native mosquitoes to arboviruses (Kramer et al. 2011), but almost no work seems to have been done for Plasmodium species. Thus, laboratory studies are necessary to determine the actual vector competence of C. pervigilans and other recorded species for transmitting different lineages of Plasmodium parasites.

References

Baillie SM, Brunton DH (2011) Diversity, distribution and biogeographical origins of Plasmodium parasites from the New Zealand bellbird (Anthornis melanura). Parasitology 138:1843–1851.

Belkin JN (1968) Mosquito studies (Diptera: Culicidae) VII. The Culicidae of New Zealand. Contributions of the American Entomological Institute 3:1–182.

Bonneaud C, Sepil I, Milá B, Buermann W, Pollinger J, Sehgal RNM, Valkiūnas G, Iezhova TA, Saatchi S, Smith TB (2009) The prevalence of avian Plasmodium is higher in undisturbed tropical forests of Cameroon. Journal of Tropical Ecology 25:439–447.

Castro I, Howe L, Tompkins DM, Barraclough RK, Slaney D (2011) Presence and seasonal prevalence of Plasmodium spp. in a rare endemic New Zealand passerine (tieke or Saddleback, Philesturnus carunculatus). Journal of Wildlife Diseases 47:860–867.

Catterall CP, Kikkawa J, Gray C (1989) Inter-related age-dependent patterns of ecology and behaviour in a population of Silvereyes (Aves: Zosteropidae). Journal of Animal Ecology 58:557–570.

Chan K (1995) Diurnal and nocturnal patterns of activity in resident and migrant silvereyes Zosterops lateralis. Emu 95:41–46.

Chasar A, Loiseau C, Valkiunas G, Iezhova T, Smith TB, Sehgal RN (2009) Prevalence and diversity patterns of avian blood parasites in degraded African rainforest habitats. Molecular Ecology 18:4121–4133.

Derraik JG, Maguire T (2005) Mosquito-borne diseases in New Zealand: has there ever been an indigenously acquired infection? New Zealand Medical Journal 118:U1670.

Derraik JG, Slaney D (2015) Notes on Zika virus—an emerging pathogen now present in the South Pacific. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 39:5–7.

Derraik JG, Slaney D, Nye ER, Weinstein P (2010) Chikungunya virus: a novel and potentially serious threat to New Zealand and the South Pacific islands. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 83:755–759.

Derraik JGB (2004) Exotic mosquitoes in New Zealand: a review of species intercepted, their pathways and ports of entry. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 28:433–444.

Derraik JGB (2005) Mosquitoes breeding in container habitats in urban and peri-urban areas in the Auckland Region, New Zealand. Entomotropica 20:93–97.

Derraik JGB (2009a) Association between habitat size, brushtail possum density, and the mosquito fauna of native forests in the Auckland Region, New Zealand. EcoHealth 6:229–238.

Derraik JGB (2009b) The mosquito fauna of phytotelmata in native forest habitats in the Auckland region of New Zealand. Journal of Vector Ecology 34:157–159.

Derraik JGB, Slaney D (2005) Container aperture size and nutrient preferences of mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) in the Auckland region, New Zealand. Journal of Vector Ecology 30:73–82.

Derraik JGB, Slaney D (2007) Anthropogenic environmental change, mosquito-borne diseases and human health in New Zealand. EcoHealth 4:72–81.

Derraik JGB, Snell AE, Slaney D (2005a) An investigation into the circadian response of adult mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) to host-cues in West Auckland. New Zealand Entomologist 28:85–90.

Derraik JGB, Snell AE, Slaney D (2005b) Vertical distribution of mosquitoes in native forest in Auckland, New Zealand. Journal of Vector Ecology 30:334–336.

Derraik JGB, Tompkins DM, Alley MR, Holder P, Atkinson T (2008) Epidemiology of an avian malaria outbreak in a native bird species (Mohoua ochrocephala) in New Zealand. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand 38:237–242.

Diamond JM (1984) Distributions of New Zealand birds on real and virtual islands. New Zealand Journal of Ecology 7:37–55.

Estoup A, Clegg SM (2003) Bayesian inferences on the recent island colonization history by the bird Zosterops lateralis lateralis. Molecular Ecology 12:657–674.

Ewen JG, Bensch S, Blackburn TM, Bonneaud C, Brown R, Cassey P, Clarke RH, Perez-Tris J (2012) Establishment of exotic parasites: the origins and characteristics of an avian malaria community in an isolated island avifauna. Ecology Letters 15:1112–1119.

Ewers RM, Kliskey AD, Walker S, Rutledge D, Harding JS, Didham RK (2006) Past and future trajectories of forest loss in New Zealand. Biological Conservation 133:312–325.

Freed LA, Cann RL (2013) Vector movement underlies avian malaria at upper elevation in Hawaii: implications for transmission of human malaria. Parasitology Research 112:3887–3895.

Funnell J, Munro U (2010) Daily and seasonal activity patterns of partially migratory and nonmigratory subspecies of the Australian silvereye, Zosterops lateralis, in captivity. Journal of Ethology 28:471–482.

Garamszegi LZ (2010) The sensitivity of microscopy and PCR-based detection methods affecting estimates of prevalence of blood parasites in birds. Journal of Parasitology 96:1197–1203.

Harvell CD, Mitchell CE, Ward JR, Altizer S, Dobson AP, Ostfeld RS, Samuel MD (2002) Climate warming and disease risks for terrestrial and marine biota. Science 296:2158–2162.

Howe L, Castro IC, Schoener ER, Hunter S, Barraclough RK, Alley MR (2012) Malaria parasites (Plasmodium spp.) infecting introduced, native and endemic New Zealand birds. Parasitology Research 110:913–923.

Kramer LD, Chin P, Cane RP, Kauffman EB, Mackereth G (2011) Vector competence of New Zealand mosquitoes for selected arboviruses. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 85:182–189.

Laird M (1950) Some blood parasites of New Zealand birds. Zoology Publications from the Victoria University College 5:1–20.

Lapointe DA (2008) Dispersal of Culex quinquefasciatus (Diptera: Culicidae) in a Hawaiian rain forest. Journal of Medical Entomology 45:600–609.

LaPointe DA, Atkinson CT, Samuel MD (2012) Ecology and conservation biology of avian malaria. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1249:211–226.

Laurance SG, Jones D, Westcott D, Mckeown A, Harrington G, Hilbert DW (2013) Habitat fragmentation and ecological traits influence the prevalence of avian blood parasites in a tropical rainforest landscape. PLoS One 8:e76227.

Loiseau C, Iezhova T, Valkiunas G, Chasar A, Hutchinson A, Buermann W, Smith TB, Sehgal RN (2010) Spatial variation of haemosporidian parasite infection in African rainforest bird species. Journal of Parasitology 96:21–29.

Martens P, Kovats R, Nijhof S, De Vries P, Livermore M, Bradley D, Cox J, McMichael A (1999) Climate change and future populations at risk of malaria. Global Environmental Change 9:S89–S107.

Massey B, Gleeson DM, Slaney D, Tompkins DM (2007) PCR detection of Plasmodium and blood meal identification in a native New Zealand mosquito. Journal of Vector Ecology 32:154–156.

Mees GF (1969). A systematic review of the Indo-Australian Zosteropidae (Part I). Zoologische Verhandelingen 102:1–390

Patz JA, Graczyk TK, Geller N, Vittor AY (2000) Effects of environmental change on emerging parasitic diseases. International Journal for Parasitology 30:1395–1405.

Reiter ME, LaPointe DA (2007) Landscape factors influencing the spatial distribution and abundance of mosquito vector Culex quinquefasciatus (Diptera: Culicidae) in a mixed residential-agricultural community in Hawai’i. Journal of Medical Entomology 44:861–868.

Ribeiro SF, Sebaio F, Branquinho FCS, Marini MÂ, Vago AR, Braga ÉM (2005) Avian malaria in Brazilian passerine birds: parasitism detected by nested PCR using DNA from stained blood smears. Parasitology 130:261–267.

Robertson CJR, Hyvonen P, Fraser MJ, Pickard CR (2007) Atlas of bird distribution in New Zealand 1999–2004. Wellington, New Zealand: Ornithological Society of New Zealand Inc., pp 254–256. ISBN 0 9582486 5 6.

Schoener E, Banda M, Howe L, Castro I, Alley M (2014) Avian malaria in New Zealand. New Zealand Veterinary Journal 62:189–198.

Sehgal RN (2010) Deforestation and avian infectious diseases. Journal of Experimental Biology 213:955–960.

Silver J (2008). Mosquito ecology: field sampling methods. Springer, Dordrecht.

Snell AE (2005) Identification keys to larval and adult female mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) of New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Zoology 32:99–110.

Stefani A, Dusfour I, Corrêa APS, Cruz MC, Dessay N, Galardo AK, Galardo CD, Girod R, Gomes MS, Gurgel H, Lima ACF, Moreno ES, Musset L, Nacher M, Soares ACS, Carme B, Roux E (2013) Land cover, land use and malaria in the Amazon: a systematic literature review of studies using remotely sensed data. Malaria Journal 12:192.

Tompkins D, Gleeson D (2006) Relationship between avian malaria distribution and an exotic invasive mosquito in New Zealand. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand 36:51–62.

Valkiunas G (2005). Avian malaria parasites and other haemosporidia. CRC Press, Boca Raton.

Valkiunas G, Iezhova TA, Krizanauskiene A, Palinauskas V, Sehgal RN, Bensch S (2008) A comparative analysis of microscopy and PCR-based detection methods for blood parasites. Journal of Parasitology 94:1395–1401.

van Riper III C, van Riper SG, Goff ML, Laird M (1986) The epizootiology and ecological significance of malaria in Hawaiian land birds. Ecological Monographs 56:327–344.

Waldbauer G (2012). Bugs that eat birds. In: A world of insects: The Harvard University Press Reader (eds. Cardé RT & Resh VH). Harvard University Press, pp. 176–181.

Wood MJ, Cosgrove CL, Wilkin TA, Knowles SC, Day KP, Sheldon BC (2007) Within-population variation in prevalence and lineage distribution of avian malaria in blue tits, Cyanistes caeruleus. Molecular Ecology 16:3263–1373.

Yasuoka J, Levins R (2007) Impact of deforestation and agricultural development on anopheline ecology and malaria epidemiology. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 76:450–460.

Young A, Mitchell N (1994) Microclimate and vegetation edge effects in a fragmented podocarp-broadleaf forest in New Zealand. Biological Conservation 67:63–72.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Tim Lovegrove and the Auckland Council for their help in funding field equipment purchases and providing lodging at Waharau. In addition, we thank Karli Stevens, Remí Bigonneau, Cécile Houllé, Ria Brejaart and the EcoQuest volunteers, for dedicating their time to help us in the field. This study was funded by Massey University and the Auckland Council.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no financial or non-financial interests to declare that may be relevant to this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gudex-Cross, D., Barraclough, R.K., Brunton, D.H. et al. Mosquito Communities and Avian Malaria Prevalence in Silvereyes (Zosterops lateralis) Within Forest Edge and Interior Habitats in a New Zealand Regional Park. EcoHealth 12, 432–440 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10393-015-1039-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10393-015-1039-y