Abstract

Aim

To transform knowledge from public health and health services research into actual improvement of services is highly relevant for spending public research resources effectively. Fostering stakeholder interaction throughout the entire research process is one potential avenue towards this aim. The objective of this paper is to look for established practices with the aim to promote the usability of research in policy and practice through interaction.

Subject and methods

We conducted 11 semi-structured telephone-interviews with senior experts from the same number of public health and health services research institutions in the Netherlands, the United Kingdom and Norway.

Results

Practice patterns are manifold, but three key domains were identified:

-

1.

Research implementation is explicitly part of the organisation’s mission. Research commissioning institutions serve as intermediaries between research, policy and practice.

-

2.

Funds are earmarked for implementation activities. In regular evaluation cycles special consideration is given to the impact of research.

-

3.

Multiple forums for interaction support the ability of researchers to actively communicate with stakeholders. Network-building skills are developed alongside scientific competence.

Conclusion

Promising initiatives can be found in practice. Further research is needed into what difference it makes how the exchange between research and policy is organised.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Health research should contribute to policies that may eventually lead to desired outcomes, including health gains (Hanney et al. 2003). Due to the difficulty of deriving generalizable findings from policy evaluation (Weiss 2000), evidence that increased research in fact improves policy and practice is contested and at best partial (Nutley et al. 2007). Theoretical literature points out that assumptions that the relationship between research and its uptake is linear and acontextual, that research can provide objective unmediated answers to policy questions and that policy-making can become a more rational process are problematic (Bijker et al. 2009; Clarence 2002; Davies 2009; Parsons 2002). Relationships between research, policy and practice are likely to remain loose, shifting and contingent (Nutley 2003). It is therefore suggested to analyse the ways in which both science and policies get shaped in their mutual interaction rather than focusing on the instrumental use of science (Bekker et al. 2010).

The issue of how to make knowledge that has been developed through public health research and health services research relevant in practice is raised regularly (Patera 2011; see also the World Report on Knowledge for Better Health: Strengthening Health Systems, WHO 2004). The European Union’s Sixth Framework Program for Research also addressed the issue in its analysis of the status quo of public health research (Strengthening Public Health Research in Europe 2011) using a broad definition of the field (McCarthy and Clarke 2007). The current Seventh Program looked at the status quo of health services research (Health Services Research Europe 2011) also using a broad definition (Lohr and Steinwachs 2002). In this context, a survey of 34 European countries (Ettelt and Mays 2011) found few mechanisms reported supporting the use of research in policy. Respondents struggled to locate information on many aspects of health services research, particularly its use in decision-making.

Model of increasing relevance through interaction

Allowing on-going relationships between researchers, research funders and potential research users as well as targeted communication with decision makers to develop is deemed important for the relevance of research (Allen et al. 2007). In a review of studies, personal contact with researchers was the most commonly reported facilitator regarding the use of research evidence by health policy makers (Innvaer et al. 2002), bringing the importance of stakeholder interaction throughout the entire research process during activities of “linkage and exchange” into focus (Goering et al. 2003). Open communication among researchers, policy makers and providers of services introduces the parties to the different environments, process dynamics and system demands and promotes mutual respect (Advisory Council on Health Research 2008). This interaction would ideally encompass the whole research process from priority setting for research and formulating research questions, to the final evaluation of research impact. Significant resources need to be invested in intelligent ways to achieve this degree of interaction (Allen et al. 2007). On the organisational level, an increase in relevance of research is facilitated by the existence of research commissioning institutions and specialized research institutions in the field of public health and health services. Their aim is not only to generate new knowledge but also to “digest” (Nutley 2003) existing research evidence, which may facilitate the opening up of evidence-informed policy debates. Trust between stakeholders and researchers, aided by intensive interaction, is a likely prerequisite for ultimate user relevance of research. The necessary capacity building requires time for a culture of problem solving in mutual respect to develop between stakeholders and researchers. A perspective on research that takes organisational and systemic perspectives on board, that understands the production of evidence as a shared process and that is sensitive to context offers the most promising way forward (Nutley et al. 2007).

Study aim

European countries have different traditions of dealing with knowledge in the area of policy-making. These traditions are influenced by the size of the country, by administrative arrangements, political structures and cultural preferences (Delvaux and Mangez 2008). The supply of research is influenced by research capacity, the volume and type of research funding, the nature of research agendas and whether researchers have incentives to engage in activities to foster research use (Nutley et al. 2010). Given the lack of even descriptive information on activities and institutional arrangements (Ettelt and Mays 2011), it was the aim of this paper to find examples of practice that focuses on stakeholder interaction in Europe that try to promote the relevance and usability of research in policy and practice by incorporating elements of the aforementioned model.

Methods

Due to a long standing and comparatively well-funded research tradition in the Netherlands and the United Kingdom (Ettelt and Mays 2011), and a culture relatively open to evidence-based policy debate, potential model organisations in the field of public health research and health services research as well as models of practice for stakeholder involvement could be expected there. In addition, Norway was included as a third country due to the convenience of prior contact.

Information available in English on potentially relevant organisations in the Netherlands, the United Kingdom and Norway was gathered on the Internet. The focus was on research organisations and on research commissioning organisations, and 11 such institutions were eventually contacted (see Table 1); however, government, administrative organisations and universities were not included. A single telephone interview with a senior expert was conducted regarding the way in which the organisation promotes stakeholder interaction aiming to encourage research relevance and usability in practice. These telephone interviews were semi-structured (the topic list tailored to each interviewed organisation can be found in the electronic supplemental material; ESM) and took place in November and December of 2010, their duration varied from 45 to 90 min. The information from the interviews was grouped and analysed according to patterns of practice.

Results

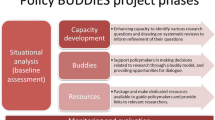

The practice patterns described by the interviewees are presented here grouped into three domains: (1) formal institutional arrangements, the framework of governance and the basic funding structure; (2) initiatives facilitating exchange at specific stages of the research process; (3) programmes that foster personal interaction with stakeholders throughout the entire research process.

Formal institutional arrangements, governance and funding

To create an environment friendly to interaction between research and stakeholders, fundamental organisational premises are essential: institutional arrangements (“Capacity for qualified research is well under way in most areas.”), governance (“Our main policy is transparency.”) and funding (“Now a 10 % implementation budget has become natural.”). Table 2 brings together issues of relevance on the organisational level touched upon in the interviews.

The United Kingdom offers examples of institutional arrangements potentially worth emulating—one of which would be the Service Delivery and Organisation Programme at the National Institute for Health Research. Commissioning research on topics like health and social integration, the management of primary care services and the implementation of research in healthcare organisations, it is an intermediary between research, policy and practice (“A system for addressing the issues of organisation of service delivery is less developed in some other countries.”).

Another example of a practice model is the Health Council of the Netherlands, whose independence from government is legally enshrined. Policy relevance is explicitly one of the requirements for research to be undertaken by the Health Council. Once the Health Council has delivered a scientific report to the minister in government overseeing the respective field of research, mostly the minister of health, a formal procedure begins. The minister is personally responsible for the implementation of the report’s findings and advice. She or he is required to state her or his position on the report to parliament and to qualify it. The minister’s response is then published online alongside the report.

In the Netherlands, the Organisation for Health Research and Development put in place a transparent system for commissioning health research which includes explicit criteria, peer referees and periodical application procedures (“Before, the commissioning of research had not been coordinated and personal contacts in the Ministry of Health were important for getting funding.”). In all, 10 % of the budget is invested in knowledge transfer and implementation aspects of commissioned research projects (“Implementation is a standard procedure, an automatic add on to research we fund.”).

Facilitating exchange at specific stages of the research process

A range of initiatives to advance relevance and usability of research focuses on certain stages of the research process such as “listening exercises” among certain stakeholders while defining the research agenda, or, towards the end of the research process, the publication of a special report on implementation activities as part of regular research evaluations. Table 3 synthesises the information on such initiatives gleaned from the expert interviews.

Organisations in the United Kingdom have experience with integrating a range of stakeholder perspectives through formal arrangements. For the commissioning of research, these may take the form of “commissioning panels”, “citizen councils” or “partner councils”, while for conducting research, the like of “stakeholder committees” may be installed.

An example of the multiple benefits of teaching activities as a dissemination measure comes from the Norwegian Knowledge Centre for Health Sciences. Since 1999, it has been organising an annual week-long workshop teaching the principles of evidence-based healthcare, guideline-making and systematic reviews to 100 participants coming from a range of stakeholder organisations. This is a considerable annual audience relative to Norway’s population size (“We teach decision makers how to formulate research questions and we make clear what kind of questions can be answered by health technology assessments.”). This forum for exchange serves multiple additional purposes—teachers from the Knowledge Center have contact with stakeholders and, through topic-focused interaction, understand better where they are coming from. It is a forum for research dissemination and a job enrichment strategy for the Knowledge Center’s staff, “to keep them longer”.

Programmes fostering personal interaction with stakeholders throughout the research process

An organisation in the field of public health research or health services research may direct its staff exchange towards universities, service providers as potential users of research or policy-making settings on national and international levels. Table 4 brings together examples of such initiatives from the expert interviews.

An example of a forum for personal interactions specifically tailored to increase the impact of research comes from the Netherlands—The National Institute for Public Health and the Environment is located in Bilthoven. Since 1995, it has been running a liaison office with a staff of six at the Ministry of Health in the capital city of The Hague. The aim is to work closely with decision makers in order to translate policy questions into researchable project formats. The liaison office assures proximity to decision makers not only at the Ministry of Health but also to other important stakeholders who interact in The Hague. Staff working at the liaison office, according to the interviewee, need to be both excellent as researchers and “to have a feeling for policy-making”, which he further clarifies: “The planning of the bridge function is essential. It is a great skill to know when to bring research results up in the policy arena.” The National Institute constantly talent scouts among its staff for individuals with these rare skills. Additionally, whenever a new minister of health takes office, a senior member of the National Institute’s staff is put at the new minister’s disposal for 6 months at the liaison office. According to the new minister’s needs, this senior expert answers questions and explains how things work in the field of health and health care. Also half-year internships for high-potential junior researchers from the National Institute are available at the Ministry of Health liaison office. Spending 1–2 days per week in The Hague and the rest of the week at the National Institute in Bilthoven allows these young researchers to gain an understanding of the system and to establish professional networks.

The English Service Delivery and Organisation Programme established a number of formal staff exchange schemes between stakeholders. The Programme funds secondments for academics to spend time working with managers in healthcare organisations. One example is through the “Academic Fellowship Scheme”, which supports senior-to-mid-level academics to spend up to a year in a partner healthcare organisation to undertake relevant health services research and develop the research skills of partner staff. In addition, research teams are given the opportunity to attend Chief Executive Officer Forums to network and share learning with senior managers of the National Health System. On the other hand, the Programme allows managers in the National Health System to work alongside researchers on research projects via the “Management Fellowship Scheme”. Here a research team integrates a local service provider manager as a formal full-time team member for the duration of the research project. Greater managerial involvement is meant to improve the quality and relevance of research. At the same time, capacity develops in the managerial community for accessing, appraising and using research evidence.

Discussion

Across the Netherlands, the United Kingdom and Norway, several examples of both formal and informal exchange models for research-stakeholder interaction to encourage relevance and usability of research prescribed in the scientific literature (Advisory Council on Health Research 2008; Allen et al. 2007; Goering et al. 2003; Innvaer et al. 2002; Nutley 2003; Nutley et al. 2007; Nutley et al. 2010) can be found implemented in practice. There are varied approaches for linking health research with national policy and practice, but no standard solutions. Research commissioning institutions are intermediaries between research findings, policy and practice. Public engagement in research commissioning aims to promote the relevance of research and research grants include funds for implementation.

There are several limitations to this study. It included only three European countries, the number of organisations in the field of public health research and health services research contacted was limited and their sampling in part reflected convenience of prior contact, information being readily available on the Internet and the possibility to conduct the telephone interviews in English. Government, administrative organisations and universities were not included. The information on models of practice presented relied on one single interview per organisation. The interviewed expert expressed views about her or his own organisation, their statements were not cross checked or independently verified. Also, the methodological limitations of telephone interviews as opposed to personal interviews or participatory observation apply.

In spite of these limitations, several prescriptions for practice models emerged. The involvement of policy makers, research commissioners, potential research users and the public in the production of research in multiple forms and during the entire research process seems promising and feasible. Creating forums for systemic interaction between researchers, potential research users and policy makers to deepen understanding, to build trust and to improve collaboration forms part of the practice models in the organisations analysed, as does institutionalising national and international networks to stay attuned to relevant developments and the provision of earmarked funding for implementation of research.

Conclusions

On the way to stakeholder orientation and sensitivity for usability of research addressed in this paper, it is equally important to safeguard the freedom and independence of research in order to maintain a challenging role for research that questions current thinking in both policy and practice (Nutley et al. 2010). Evidence-based approaches towards decision-making need to be balanced with participatory or “people based” ones (Quinn 2002). This process is resource intensive and is not likely to yield results in the short term. At this stage, it remains unclear whether the presented models of practice succeeded in making public health and health services research more relevant. The question of what difference it makes how the exchange between research and policy and practice is organised needs to be addressed in future research. After our exploratory approach, wider, more systematic and more resource intensive studies of the issue are called for. More knowledge of how to optimise the benefit of public health research for policy and practice is needed.

References

Advisory Council on Health Research (2008) Healthy services research. The future of health services research in The Netherlands (in Dutch, executive summary in English). RGO no. 59, Health Council of the Netherlands, The Hague

Allen P, Peckham S, Anderson S, Goodwin N (2007) Commissioning research that is used: the experience of the NHS service delivery and organisation research and development programme. Evid Policy 3(1):119–134

Bekker M, van Egmond S, Wehrens R, Putters K, Bal R (2010) Linking research and policy in Dutch healthcare: infrastructure, innovations and impacts. Evid Policy 6(2):237–253

Bijker WE, Bal R, Hendriks R (2009) Paradox of scientific authority: the role of scientific advice in democracies. MIT Press, Boston, MA

Clarence E (2002) Technocracy reinvented: the new evidence-based policy movement. Publ Policy Admin 17(3):1–11

Davies H (2009) Co-producing knowledge? Presentation at the Economic and Social Research Council research seminar series. St. Andrews, UK. Nov 2009. www.sdhi.ac.uk/pastevents.htm#ESRC. Accessed 15 Jan 2011

Delvaux B, Mangez E (2008) Towards a sociology of the knowledge-policy relation. Literature review. http://knowandpol.eu/IMG/pdf/literature_sythesis_final_version_english.pdf. Accessed 15 Jan 2011

Ettelt S, Mays N (2011) Health services research in Europe and its use for informing policy. J Health Serv Res Policy 16(7):48–60

Goering P, Butterill D, Jacobson N, Sturtevant D (2003) Linkage and exchange at the organizational level: a model of collaboration between research and policy. J Health Serv Res Policy 8(Suppl 2):14–19

Hanney SR, Gonzalez-Block MA, Buxton MJ, Kogan M (2003) The utilization of health research in policy-making: concepts, examples and methods of assessment. Health Res Policy Syst 1(1):2

Health Services Research Europe (2011) www.healthservicesresearch.eu. Accessed 15 Jan 2011

Innvaer S, Vist G, Trommald M, Oxman A (2002) Health policy-makers’ perceptions of their use of evidence: a systematic review. J Health Serv Res Policy 7:239–244

Lohr KN, Steinwachs DM (2002) Health services research: an evolving definition of the field. Heal Serv Res 37:15–17

McCarthy M, Clarke A (2007) European public health research literatures: measuring progress. Eur J Public Health 17(Suppl 1):2–5

Nutley S (2003) Bridging the policy/research divide: reflections and lessons from the UK. Keynote paper presented at the National Institute of Governance Conference, Canberra, Australia, 23–24 April 2003. www.treasury.govt.nz/publications/media-speeches/guestlectures/pdfs/tgls-nutley.pdf. Accessed 15 Jan 2011

Nutley S, Walter I, Davies HTO (2007) Using evidence: how research can improve public services. The Policy Press, Bristol, UK

Nutley S, Morton S, Jung T, Boaz A (2010) Evidence and policy in six European countries: diverse approaches and common challenges. Evid Policy 6(2):131–144

Parsons W (2002) From muddling through to muddling up: evidence based policy making and the modernisation of British government. Publ Policy Admin 17(3):43–60

Patera N (2011) Strengthening the knowledge base for a better health system: inspirations from good practice for capacity building in health services research and public health research. HTA project report No. 48, Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Health Technology Assessment, Vienna

Quinn M (2002) Evidence based or people based policy making? A view from Wales. Publ Policy Admin 17(3):29–42

Strengthening Public Health Research in Europe (2011) www.ucl.ac.uk/public-health/sphere. Accessed 15 Jan 2011

Weiss CH (2000) Which links in which theories shall we evaluate? In: Rogers PJ, Petrosino A, Heuber TA, Hascia TA (eds) Program theory evaluation: practice, promise and problems. New Directions Eval 87:35–45

WHO (2004) World report on knowledge for better health: strengthening health systems. World Health Organization, Geneva

Conflicts of interest

None declared

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(DOC 42 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Patera, N., Wild, C. Linking public health research with policy and practice in three European countries. J Public Health 21, 473–479 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-013-0556-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-013-0556-9