Abstract

Aim

A randomised field trial was conducted to evaluate a school-based programme to prevent tobacco use in children and adolescents.

Subject and methods

The trial included 534 children and 308 adolescents who were randomly selected to receive or not to receive the prevention programme. The prevention programme included: (a) health facts and the effect of smoking, (b) analysis of the mechanisms underlying intiation of smoking and (c) refusal skills training to deal with the social pressures to smoke. A questionnaire was administered before the intervention programme and 2 years later.

Results

The prevalence rates of smoking in both groups of children and adolescents were increased at the end of the study. Anyway, the difference of smoking prevalence between the intervention and control groups was statistically significant only for the children’s group (from 18.3 to 18.8% for the intervention group and from 17.8 to 26.9% in the control group) (p = 0.035). As regards reasons that induced the start of smoking, there was a significant increase of the issue “because smokers are fools” (p = 0.004 for children; p < 0.001 for adolescents) and “because smokers are irresponsible” (p ≤ 0.001 for both children and adolescents) in the experimental groups.

Conclusion

The results suggest that a school-based intervention programme addressing tobacco use among children and adolescents, based on the development of cognitive and behavioural aspects, can be effective. After 1 year of intervention, smoking prevalence was significantly lower in children belonging to the intervention group than in children not randomised to intervention. Targeting young children before they begin to smoke can be a successful way of prevention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

It has been definitively demonstrated that smoking represents the most important preventable cause of different diseases and premature death. Smoking causes 5 million deaths worldwide per year, and if present trends continue, by 2025 10 million smokers per year are projected to die (Hatsukami et al. 2008).

Anyway, cigarette smoking is actually the most widespread addictive behaviour in Italy, such as in all developed countries, and this is particularly true among young people (Evans 1976; Pampel and Aguilar 2008; Ferketich et al. 2008).

An efficacious fight against smoking could be based on three factors: (1) ban of direct and indirect advertising, (2) smoking prohibition in public rooms and (3) health education and promotion.

Most people start smoking during adolescence. The aetiological model is based on psychological and environmental pressure, especially due to parents and peers, and on smoking advertising, which are responsible for inducing and perpetuating a smoking habit (Farrelly 2009).

The essential elements of smoking prevention interventions, as suggested by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), include: (1) information about social influences, including media, peer and parents, (2) information about short-term physiological effects of tobacco use and (3) training in refusal skills. In fact, there is a sufficient body of evidence indicating that the most efficacious preventive approach must be based not only on information, but on developing and reinforcement of refusal skills training for dealing with the social pressures to smoke (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 1994; Ajzen and Fishbein 1980; Botvin and Griffin 2007; Peters et al. 2009).

As far as concerns the best age period to start tobacco smoking prevention programmes, many researchers agree to initiate them at elementary schools, because programmes started at high schools were found to be less effective.

In the literature there are many studies focused on smoking prevention programmes in adolescent populations (Puska et al. 1981; Clarke et al. 1986; Errecart et al. 1991; Perry et al. 1992; Adelman et al. 2001; La Torre et al. 2004; Resnicow et al. 2008; Campbell et al. 2008; Johnson et al. 2009), while very few studies on interventions in children have been conducted (Best et al. 1988; Rasmussen et al. 2002; Thomas and Perera 2006; Hiemstra et al. 2009).

In order to assess the effectiveness of a smoking prevention programme in children and adolescents (grade 4–9), we conducted a school-based prevention trial in three different towns of Central and Southern Italy: in Cassino and Pontecorvo (Lazio region) and Capodrise (Campania region). This study, taking into account both adolescents and children, gives the possibility to analyse the differences between the results obtained by two similar interventions administered to both groups. Moreover, the intervention focalises—in addition to information on health facts—on refusal skills training to enable the children and adolescents to deal with the social pressures to smoke.

Methods

Setting and questionnaire

The trial was conducted in three cities (Cassino, Pontecorvo and Capodirise), the first two in the Lazio region and the latter in the Campania region. However, despite the different regions, the cities are very close (10 km between Cassino and Pontecorvo, and 75 km between Cassino and Capodrise), without major socio-demographic disparities able to influence the results of the trials differently.

Adolescent trial

In February 1999 an anonymous questionnaire was administered to adolescents attending high schools in grade 9 (ages 14–15) to evaluate the prevalence of smoking and attitude towards tobacco. Fifteen classes of the Classical and Scientific Licea of Cassino (Province of Frosinone, Lazio) were selected to be enrolled in the study.

Children’s trial

Moreover, the same questionnaire was administered to children attending schools in grades 4–6 (ages 9–11) in Pontecorvo (Province of Frosinone, Lazio) and Capodrise (Province of Caserta, Campania) in May 2002.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire, validated in previous cross-sectional studies, was designed to collect socio-demographic information about students and their parents, habits and attitudes towards tobacco and passive smoking (La Torre et al. 1998). The main outcome variable was represented by the following question: “Have you ever smoked a cigarette?”, indicating the status of current or ex-smoker. The questionnaire was submitted twice: before the intervention programme and 2 years later.

The participation in the trial was accepted by each school Health Promotion Committee and a written consent was obtained from students’ parents. The trial was conducted following the criteria of the Helsinki Declaration.

Health education intervention

The tobacco smoking prevention programme was designed as a school-based intervention focused on avoiding students’ use of tobacco through a clarification of facts. The curriculum consists of three levels of instruction: (1) health facts and the effect of smoking on health, (2) analysis of the mechanisms that lead children and adolescents to start smoking and (3) refusal skills training for dealing with the social pressures to smoke.

The intervention was scheduled on a basis of five appointments, the first and the last ones delivered by the schools’ teachers involved in the project. These teachers were trained through a tobacco prevention course, organised 1 month before the start of the intervention by the scientist responsible for the project. From the second to the fourth appointments, the participants in the experimental groups underwent the intervention that lasted for 2 h each. Finally, the teachers of the involved schools reinforced the intervention in a last appointment.

In the intervention group, the short-term more than the long-term effects of smoking were emphasised, and students were allowed to clarify their opinions regarding tobacco use. Moreover, peer-led discussions and skills practice activities were performed.

The curriculum underlined psycho-social themes, such as relational stress within peer groups and family, that can influence and perpetuate the attitude towards tobacco, as well as economic aspects related to the cultivation of tobacco plants (the intervention was conducted in a tobacco production zone). The intervention was aimed at developing the capability of children to firmly and politely refuse cigarettes offered by peers and to maintain a conversation in order to adequately sustain their refusal position.

The participants followed the programme for 1 year. One more year later, the questionnaire was administered again to both students that received and did not receive the intervention programme, in order to assess differences in the prevalence of smoking in the intervention and in the control groups.

At the end of the intervention, students in the experimental arm were asked to fill in a questionnaire on the quality of the intervention, considering the following items:

-

Interest in the issues covered in the intervention

-

Comprehensiveness of the intervention

-

Availability of the intervention teaching staff to answer questions

-

Usefulness of the intervention

Thanks to a strong collaboration with teachers responsible for health education in the selected schools, it was possible to follow students’ careers in order to avoid loss to follow-up in the trial.

Sample size and randomisation

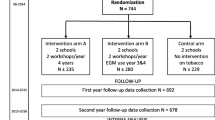

Sample size calculations, with a sensitivity of 90% and a power of 80%, an expected frequency of smoking of 30% and an estimated odds ratio (OR) of smoking equal to 0.70 for students participating in the intervention groups suggested that 778 individuals be sampled. We did not calculate the number of classes to accrue, since the outcome of the trial was at the individual level and not at the class level. So, considering an average class composed of 20 students, we estimated that a total of 39 classes were needed for the trials. On the basis of the total number of classes in the selected schools, and considering the proportion of children and adolescents at schools in the cities involved, we randomised 24 elementary classes and 15 high school classes to both intervention or control groups. The randomisation process resulted in the scheme shown in Fig. 1: in the children’s group, 242 pupils were randomised to the experimental group and 292 to the control group; in the adolescent group, 162 and 146 students were randomised to intervention and control groups, respectively.

Sample size calculations were made using the program Statcalc in Epi Info statistical package.

Statistical analysis

The chi-square test, with Yates’ correction where applicable, and Fisher’s exact test were used to assess statistically significant differences between questionnaire answers at the beginning and at the end of the trial in the two groups.

In order to estimate the influence of socio-demographic factors on the cigarette smoking attitudes of both children and adolescents, multiple logistic regression analyses were performed, using the backward elimination procedure described by Hosmer and Lemeshow (Hosmer and Lemeshow 1989).

The covariates considered in the models were: gender (males as reference group), age of children, parents’ smoking habits (no smokers as reference group) and father’s job activity (managerial status as reference group). The results are expressed as OR and 95% confidence interval (95% CI). The goodness of fit was assessed using the Hosmer-Lemeshow test. The level of statistical significance was fixed at p = 0.05.

To evaluate the effectiveness of the smoking prevention programme, the percentage of the outcome variable (smoking status) variation in the intervention group (experimental event rate, EER) and in the control group (control event rate, CER) was calculated for each subgroup and globally. Finally, the absolute risk reduction (ARR), the relative risk reduction (RRR) and the number needed to prevent an event (NNT = 1/ARR) were calculated.

Moreover, a different analysis was conducted in order to take into account cluster randomisation. We followed the methods suggested by Donner and Klar (2000), using adjustments for the chi-square test and generalised estimating equations (GEE) in order to construct an extension of standard logistic regression which adjusts for the effect of clustering, without requiring parametric assumptions.

The statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS for Windows (release 12.0) and Stata 9.

Results

Children’s trial

A total of 242 students were enrolled in the study in the intervention group (125 male subjects, mean age: 11.03 years, SD = 1.07), and 292 students were enrolled in the control group (146 male subjects, mean age: 11.01 years, SD = 0.96).

Table 1 shows the socio-demographic characteristics of the pupils, indicating that no differences existed between the two groups at baseline.

In Table 2 the prevalence of smoking in the two groups at the beginning and at the end of the trial are shown. The prevalence of smoking in the intervention group was revealed to be quite constant, going from 18.3 to 18.8%, while a relevant increase was observed in the control group, rising from 17.8 to 26.9% (p = 0.035; cluster randomised analysis p = 0.042).

Table 3 shows data relative to changes in knowledge and attitude towards tobacco smoking, both in the experimental and control groups. It is interesting to note that the smoking prevention programme is considered to be useful mostly in the experimental group (p = 0.019; cluster randomised analysis p = 0.026).

As regards reasons that induced the start of smoking, in the experimental group there was a significant increase regarding the issue “because smokers are fools” (p = 0.004; cluster randomised analysis p = 0.012 ) and “because smokers are irresponsible” (p = 0.001; cluster randomised analysis p = 0.019).

In Italy, advertising of tobacco products has been banned since 1962 but remains in the form of indirect advertising, like the brand related to sponsorship, particularly of sporting events. In both groups the prevalence of children remembering indirect cigarette advertising was very high (almost 40% at the end of the trial), mostly related to the Formula 1 Ferrari-Marlboro Team.

As far as concerns effectiveness of the community intervention to prevent tobacco use by children, after 2 years, the EER) was 0.5%, while the CER was 9.1% and the RRR of being smokers for children randomised to the intervention group was 94.5%. An interesting indicator for assessing the intervention effectiveness is the NNT, which in our experience is 11.6, i.e. we need to treat 11–12 children (equivalent to half a class) in order to have a child that remains a non-smoker in 1 year.

Significant predictors of tobacco smoking in the children’s trial were age (OR = 1.32 for one unit increase) and belonging to the control group (risk almost doubled with respect to intervention group; cluster randomised analysis OR = 0.76; p = 0.023) (Table 4).

Adolescent’s trial

A total of 162 adolescents were enrolled in the intervention group (77 male subjects, mean age: 14.39 years, SD = 0.7), and 146 adolescents were enrolled in the control group (70 male subjects, mean age: 14.33 years, SD = 0.69).

The socio-demographic characteristics of the participants in the trial are shown in Table 1, indicating that no differences existed between the intervention and control groups at baseline.

The prevalence rates of smoking at the beginning and at the end of the study are shown in Table 2. It is remarkable that in the second year of the trial the prevalence rates of smoking increased in both groups: in the intervention group it went from 16.9 to 29.4%, while in the control group it rose from 18.5 to 33.4%, even if the increases were not statistically significant. Since within-cluster correlation was near 0, we considered Pearson’s chi-square test as appropriate.

Table 5 presents data regarding variations in knowledge and attitude towards tobacco smoking in the two periods, both in the experimental and control groups. Among reasons that induced the start of smoking, in the experimental group there was a significant increase regarding the issue “to be part of a group with peers” (p = 0.001), “because parents smoke” (p < 0.001), “because smokers are fools” (p < 0.001) and “because smokers are irresponsible” (p < 0.001).

In the intervention group there was a significant increase of thinking that passive smoking was harmful (p = 0.015; cluster randomised analysis p = 0.053) and of knowledge about direct advertising in Italy (p = 0.005; cluster randomised analysis p = 0.037). The prevalence of adolescents remembering indirect cigarette advertising significantly increased in both groups.

Moreover, also the prevalence of adolescents that felt themselves uncomfortable when someone smokes in their presence significantly increased in both groups.

As far as concerns effectiveness of the community intervention to prevent tobacco use by adolescents, it should be underlined that the EER was 12.5%, while the CER was 14.9%. The RRR of being smokers for adolescents randomised to the intervention group was 16.1%. The NNT was 41.7, i.e. we need to treat 42 adolescents (equivalent to approximately two classes) in order to have an individual that remains a non-smoker in 1 year.

Significant predictors of tobacco smoking in the adolescent’s trial were age (OR = 2.01 for one unit increase) and the status of current smoker of the father (OR = 1.88) (Table 4). Considering the cluster randomised analysis, the ORs were 1.89 and 1.73, respectively.

Both children and adolescents

Considering all participants in the trial, the EER was 5.6%, while the CER was 10.9%. The NNT was 18.9, i.e. we need to treat 19 individuals (equivalent to approximately one class) in order to have an individual that remains a non-smoker in 1 year. At the end of the intervention trial the following judgments were found in the intervention group:

-

Interest in the issues covered in the intervention: 95%

-

Comprehensiveness of the intervention: 97%

-

Availability of the intervention teaching staff to answer questions: 99%

-

Usefulness of the intervention: 91%

The logistic regression (Table 4) showed that cigarette smoking among children was significantly associated to the status of current smoker of the father (OR = 1.90; 95% CI: 1.33–2.70) and increasing age (OR = 1.18 for one unit increase; 95% CI: 1.11–1.26).

Discussion

The results suggest that a school-based intervention on tobacco use by children, based on the development of cognitive and behavioural aspects, can be effective in the Italian setting, especially for children. After 1 year of intervention, smoking prevalence was significantly lower in children who received the community intervention programme than in children not randomised to intervention. The adolescent’s trial did not have the same results, and this finding is in line with a systematic review of controlled trials for adolescent smoking cessation (Garrison et al. 2003) which demonstrated that there is very limited evidence of efficacy of smoking cessation interventions in adolescents and no evidence on the long-term effectiveness of these interventions. Despite similar intervention and social characteristics of the two settings, the prevention does not work in the same way. The deepest differences between the two groups of intervention are likely imputable to the age of the participants. If the onset of smoking occurs predominantly during adolescence, maybe this age is too late to start an effective prevention programme, and targeting young children before they begin to smoke can be a successful way of prevention.

In this trial the high prevalence of ever smoking among children and adolescents at baseline must not be surprising, since the towns chosen are located in areas of tobacco production, and this is witnessed mainly by the prevalence of smoking in parents, which is very high with respect to the Italian average where 24.5% of the population smoke (32.4% men and 17.1% women) (Istat 2000).

The findings are consistent with other studies of community interventions to prevent tobacco use by children and adolescents (Clarke et al. 1986; Perry et al. 1992, 2009; Resnicow et al. 2008; Campbell et al. 2008; Rasmussen et al. 2002; Faggiano et al. 2008). A recent review of the scientific literature underlines the need to reinforce smoking prevention programmes even at very young ages (elementary school) and the need to use the school environment as a fundamental place to prevent smoking (La Torre et al. 2005; Sherman and Primack 2009).

Many systematic reviews demonstrate that school-based smoking prevention programmes are effective in reducing smoking habits, if conducted in a methodologically rigorous way (Rundall and Bruvold 1988; Bruvold 1993; Rooney and Murray 1996; Thomas 2002; Sowden et al. 2003; Hwang et al. 2004; Thomas and Perera 2006; Richardson et al. 2009).

They show evidence of a decreased prevalence of smoking among students exposed to the social influence programmes compared to students in control groups, with the mean difference between treated and non-treated groups (schools or classrooms) ranging from 5 to 60%, with a duration of 1–4 years.

In this context, the Control of Adolescent Smoking Study (CAS) is an interesting survey that investigated the relationships between national tobacco policies, school smoking policies and adolescent smoking in eight European countries (Austria, French-speaking Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Norway, Scotland and Wales). The CAS study suggested that the prevalence of smoking among students was related to the strength and enforcement of policies to control smoking and good teacher support for students was correlated with lower smoking rates in students; therefore the main recommendation from the CAS study is to aim for smoke-free schools and support this aim with comprehensive national tobacco control policies (Wold et al. 2004). On the other hand, it would be necessary to act at different levels in the community, also implementing training programmes among health care personnel in order to develop ability in smoking cessation techniques for providing active support to smokers (Gianti et al. 2007).

It is evident that school programmes designed to prevent tobacco use in children and adolescents could become one of the most effective strategies available to reduce tobacco use all over the world, especially if the programme comprehends the involvement of communities.

The present trial has some limitations. First of all, the trial was designed having the class as the randomisation unit. In this way, the effect of the intervention could have been diluted by the impossibility of taking completely separated participants in the trial within the same school. Anyway, if this happened, the results suggest the positive influence of the intervention. Another critical point is the duration of follow-up. Our trial was designed to study the effect of the intervention in the short medium term, and obviously we were not able to show the long-term effect of the same intervention. Moreover, a possible selection bias could have occurred since we recruited the participants in two different periods (1999 and 2002), but it is unlikely that time trends could have affected the results, due to the short period, and no new tobacco control measures were implemented in Italy during that period. We were not able to apply the same standardised intervention to children in the same grade due to logistic reasons. Finally, a possible dilution of the effect could not have been avoided at all, especially in the adolescent trial, due to the objective difficulty (or even impossibility) of avoiding communication between adolescents who belong to different classes (involved and not involved in the experimental groups).

The major strength of this trial was the possibility to fully follow up the participants, due to the collaboration of the selected schools. Our intervention was greatly appreciated by the school personnel and demonstrates once again that the school setting is one of the best environments in which an educational intervention could be implemented.

References

Adelman WP, Duggan AK, Hauptman P, Joffe A (2001) Effectiveness of a high school smoking cessation program. Pediatrics 107:E50–E56

Ajzen I, Fishbein M (1980) Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs

Best JA, Thomson SJ, Santi SM, Smith E, Brown KS (1988) Preventing cigarette smoking among school children. Annu Rev Public Health 9:161–201

Botvin GJ, Griffin KW (2007) School-based programmes to prevent alcohol, tobacco and other drug use. Int Rev Psychiatry 19:607–615

Bruvold WH (1993) A meta-analysis of adolescent smoking prevention programs. Am J Public Health 83:872–880

Campbell R, Starkey F, Holliday J, Audrey S, Bloor M, Parry-Langdon N, Hughes R, Moore L (2008) An informal school-based peer-led intervention for smoking prevention in adolescence (ASSIST): a cluster randomised trial. Lancet 371:1595–1602

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1994) Guidelines for school health programs to prevent tobacco use and addiction. MMWR Recomm Rep 43:1–18

Clarke JH, MacPherson B, Holmes DR, Jones R (1986) Reducing adolescent smoking: a comparison of peer-led, teacher-led, and expert interventions. J Sch Health 56:102–106

Donner A, Klar N (2000) Design and analysis of cluster randomization trials in health research. Arnold, London

Errecart MT, Walberg HJ, Ross JG, Gold RS, Fiedler JL, Kolbe LJ (1991) Effectiveness of teenage health teaching modules. J Sch Health 61:26–30

Evans RI (1976) Smoking in children: developing a social psychological strategy of deterrence. Prev Med 5:122–127

Faggiano F, Galanti MR, Bohrn K et al (2008) The effectiveness of a school-based substance abuse prevention program: EU-Dap cluster randomised controlled trial. Prev Med 47:537–543

Farrelly MC (2009) Monitoring the tobacco use epidemic V. The environment: factors that influence tobacco use. Prev Med 48:S35–S43

Ferketich AK, Gallus S, Iacobelli N, Zuccaro P, Colombo P, La Vecchia C (2008) Smoking in Italy 2007, with a focus on the young. Tumori 94:793–797

Garrison MM, Christakis DA, Ebel BE, Wiehe SE, Rivara FP (2003) Smoking cessation interventions for adolescents: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med 25(4):363–367

Gianti A, Vianello S, Casinghini C, Roncarolo F, Ramella F, Maccagni M, Tenconi MT (2007) The “Quit and Win” campaign to promote smoking cessation in Italy: results and one year follow-up across three Italian editions (2000–2004). Ital J Public Health 5:59–64

Hatsukami DK, Stead LF, Gupta PC (2008) Tobacco addiction. Lancet 371:2027–2038

Hiemstra M, Ringlever L, Otten R, Jackson C, van Schayck OC, Engels RC (2009) Efficacy of smoking prevention program ‘Smoke-free Kids’: study protocol of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health 9:477

Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S (1989) Applied logistic regression. Wiley, New York

Hwang MS, Yeagley KL, Petosa R (2004) A meta-analysis of adolescent psychosocial smoking prevention programs published between 1978 and 1997 in the United States. Health Educ Behav 31:702–719

Istat (2000) I cittadini e l’ambiente. Indagine multiscopo sulle famiglie. Aspetti della vita quotidiana [The citizens and the environment. A multiscope survey on families, daily aspects]. Istat, Roma

Johnson CC, Myers L, Webber LS, Boris NW, He H, Brewer D (2009) A school-based environmental intervention to reduce smoking among high school students: the Acadiana Coalition of Teens against Tobacco (ACTT). Int J Environ Res Public Health 6:1298–1316

La Torre G, Langiano E, De Vito E, Soave G, Ricciardi G (1998) Abitudine al fumo di tabacco negli studenti universitari: risultati di un'indagine campionaria sugli studenti di Cassino. [Tobacco smoking habits among university students: results of a sample survey in Cassino]. Ig Mod 110:377–387

La Torre G, Moretti C, Capitano D, Alonzi MT, Ferrara M, Gentile A, Mannocci A, Capelli G (2004) La prevenzione del tabagismo: risultati di uno studio controllato randomizzato in adolescenti scolarizzati in Cassino. [Tobacco prevention: results of a randomised controlled trial among adolescents in Cassino]. Riv Ital Med Adolesc 2:36–40

La Torre G, Chiaradia G, Ricciardi G (2005) School-based smoking prevention in children and adolescents: review of the scientific literature. J Public Health 13:285–290

Pampel FC, Aguilar J (2008) Changes in youth smoking, 1976–2002: a time-series analysis. Youth Soc 39:453–479

Perry CL, Kelder SH, Murray DM et al (1992) Communitywide smoking prevention: long-term outcomes of the Minnesota Heart Health Program and the Class of 1989 Study. Am J Public Health 82:1210–1216

Perry CL, Stigler MH, Arora M, Reddy KS (2009) Preventing tobacco use among young people in India: Project MYTRI. Am J Public Health 99:899–906

Peters LW, Wiefferink CH, Hoekstra F, Buijs GJ, Ten Dam GT, Paulussen TG (2009) A review of similarities between domain-specific determinants of four health behaviors among adolescents. Health Educ Res 24:198–223

Puska P, Vartiainen E, Pallonen U et al (1981) The North Karelia Youth Project. A community-based intervention study on CVD risk factors among 13- to 15-year-old children: study design and preliminary findings. Prev Med 10:133–148

Rasmussen M, Damsgaard MT, Due P, Holstein BE (2002) Boys and girls smoking within the Danish elementary school classes: a group-level analysis. Scand J Public Health 30:62–69

Resnicow K, Reddy SP, James S et al (2008) Comparison of two school-based smoking prevention programs among South African high school students: results of a randomized trial. Ann Behav Med 36:231–243

Richardson L, Hemsing N, Greaves L, Assanand S, Allen P, McCullough L, Bauld L, Humphries K, Amos A (2009) Preventing smoking in young people: a systematic review of the impact of access interventions. Int J Environ Res Public Health 6:1485–1514

Rooney BL, Murray DM (1996) A meta-analysis of smoking prevention programs after adjustment for errors in the unit of analysis. Health Educ Q 23:48–64

Rundall TG, Bruvold WH (1988) Meta-analysis of school-based smoking and alcohol use prevention programs. Health Educ Q 15:317–334

Sherman E, Primack BA (2009) What works to prevent adolescent smoking? A systematic review of the National Cancer Institute’s research-tested intervention programs. J Sch Health 79:391–399

Sowden A, Arblaster L, Stead L (2003) Community interventions for preventing smoking in young people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1:CD001291

Thomas R (2002) School-based programmes for preventing smoking. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 4:CD001293

Thomas RE, Perera R (2006) School-based programmes for preventing smoking. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev 3:CD001293

Wold B, Torsheim T, Currie C, Roberts C (2004) National and school policies on restrictions of teacher smoking: a multilevel analysis of student exposure to teacher smoking in seven European countries. Health Educ Res 19:217–226

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the Heads and the teachers of the schools involved, particularly for their valuable contribution Prof. Lea Monte of “Comprensivo di Capodrise” (CE) and Prof. Claudia Moretti of Liceo Scientifico “Pellecchia”, Cassino (FR).

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

La Torre, G., Chiaradia, G., Monte, L. et al. A randomised controlled trial of a school-based intervention to prevent tobacco use among children and adolescents in Italy. J Public Health 18, 533–542 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-010-0328-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-010-0328-8