Summary

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is a global threat to public health. This study is the first report of the emergence of vancomycin-resistant MRSA in Kerman, Iran. During a period of 15 months, a total of 205 clinical isolates of S. aureus were collected from three university hospitals affiliated with the Kerman University of Medical Science, Kerman, Iran. Screening of methicillin and vancomycin resistance was carried out by phenotypic methods. The resistance and virulence genes of vancomycin-resistant isolates were detected by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) and spa typing were used for molecular typing of vancomycin-resistant isolates. Two S. aureus isolates were considered vancomycin-resistant by phenotypic and genotypic methods. Both isolates showed a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) ≥ 64 µg/ml and belonged to SCCmec III and spa type t030. Finding vancomycin-resistant S. aureus (VRSA) isolates represents a serious problem. More stringent infection control policies are recommended to prevent transmission of such life-threatening isolates in the hospital setting.

Zusammenfassung

Der methicillinresistente Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) ist eine weltweite Bedrohung der öffentlichen Gesundheit. Die vorliegende Arbeit stellt den ersten Bericht über das Aufkommen vancomycinresistenter MRSA in Kerman, Iran, dar. Innerhalb von 15 Monaten wurde insgesamt 205 klinische Isolate von S. aureus aus 3 Universitätskliniken gesammelt, die der Medizinischen Fakultät der Universität Kerman angeschlossen sind. Das Screening auf Methicillin- und Vancomycinresistenz wurde anhand phänotypischer Verfahren durchgeführt. Die Resistenz- und Virulenzgene vancomycinresistenter Isolate wurden mittels Polymerasekettenreaktion („polymerase chain reaction“, PCR) nachgewiesen. Die Staphylococcal-Cassette-Chromosome-mec(SCCmec)- und -spa-Typisierung wurden zur molekularen Typisierung vancomycinresistenter Isolate eingesetzt. Anhand phänotypischer und genotypischer Verfahren wurden 2 S.-aureus-Isolate als vancomycinresistent angesehen. Beide Isolate zeigten eine minimale Hemmkonzentration („minimum inhibitory concentration“, MIC) ≥ 64 µg/ml und gehörten zum SCCmec-III- und -spa-Typ t030. Der Befund vancomycinresistenter S.-aureus(VRSA)-Isolate stellt ein ernstes Problem dar. Strengere Strategien für die Infektionsüberwachung werden zur Prävention der Übertragung derartiger lebensbedrohlicher Isolate in Krankenhäusern empfohlen.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is considered as one of the most important multiple drug resistant (MDR) pathogens in intensive care units (ICUs) [1, 2]. Over the past decades, the incidence of MRSA isolates has increased dramatically worldwide [2]. Vancomycin is a drug of choice for the treatment of MDR S. aureus infections [3]. Resistance to vancomycin can be linked to the presence of the vanA gene or thickening of the bacterial cell wall [4]. Vancomycin resistant S. aureus (VRSA) was first reported in the USA in 2002 [5]. By the end of 2015, several VRSA strains had been reported in different countries, which made treatment more complicated [5, 6]. The first VRSA isolate from Iran was reported in Tehran in 2008 [7]. Herein, the authors describe the emergence of the first VRSA isolates from two hospitalized patients in Kerman, southeastern Iran.

Materials and methods

From February 2015 to May 2016, 205 S. aureus isolates were collected from patients admitted to three university hospitals affiliated with the Kerman University of Medical science in Kerman, Iran. These isolates were obtained from various samples such as urine, blood, cerebrospinal fluid, wound and respiratory tract. All isolates were identified as S. aureus by positive Gram staining, as well as positive tests for catalase, coagulase, DNAse and fermentation of mannitol [8]. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-mediated amplification of the nuc gene was performed to confirm these isolates genotypically [9].

The antibiotic susceptibility profile of isolates was determined by the disk diffusion method according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) recommendations [10]. The following antibiotic disks were employed: gentamicin (10 µg), amikacin (30 µg), erythromycin (15 µg), clindamycin (2 µg), tetracycline (30 µg), ciprofloxacin (5 µg), trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (1.25/23.75 µg) and linezolid (30 µg). Screening for MRSA and VRSA isolates was carried out by detection of resistance to a cefoxitin disk (30 µg) and growing on Brain Hearth Infusion agar (BHI; Difco, BD, NJ, USA) containing 6 µg/ml vancomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA), respectively. Also, the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of vancomycin was determined using the broth microdilution method. S. aureus ATCC 29213 and Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212 were used as standard strains in the antimicrobial susceptibility tests.

The total genomic DNA of VRSA strains was extracted by Exgene™ Clinic SV (GeneALL, Seoul, Korea) according to manufacturer’s guidelines. The oligonucleotide primers used for amplification of the mecA, vanA, vanB, ermA, ermB, ermC, mrsA/B and pvl genes are listed in Table 1. The PCR amplifications for the above genes were carried out as described previously [11–13]. Finally, SCCmec and spa typing was performed as described previously [14, 15].

Results

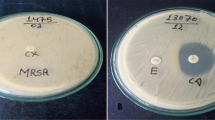

In this study, 100 (48.78%) of the 205 isolates were determined as MRSA by phenotyping methods. Two MRSA isolates were identified as VRSA and both isolates were vanA positive (Fig. 1). These isolates were from two women with pneumonia, hospitalized in the same ICU. It is not known exactly how long these women were hospitalized before specimen collection, but it is clear that the specimens had been collected at least 4 days after hospitalization. One of the isolates had been obtained in February 2015 from the bronchial aspirate of a 76-year-old woman with a history of diabetes mellitus and haemodialysis, who was not treated and died. According to our information, this patient had been admitted to the ICU on arrival. The other isolate had been obtained in April 2015 from the bronchial aspirate of a 66-year-old woman with pneumonia. This patient had been transferred from the urology unit (no further data available). Both VRSA isolates were resistant to gentamicin, amikacin, erythromycin, clindamycin, tetracycline, ciprofloxacin, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and cefoxitin, but they were susceptible to linezolid. Genetic characteristics of and clinical information pertaining to these isolates are shown in Table 2.

Discussion

During the past decade, VRSA strains have been reported from different countries such as the USA, Portugal and India [3, 5, 6]. This study is the first report of the emergence of VRSA in the southeast of Iran. In contrast to previously reported VRSA isolates that were susceptible to gentamicin and other antibiotics [2–8], the isolates presented here showed a MDR phenotype. Although MRSA strains with SCCmec III and spa t030 have been reported from different countries, such as China, Germany, Denmark, Sweden and even other regions in Iran, none of them showed vancomycin resistance [16–19]. VRSA strains with spa type t292 (SCCmec IV) and t019 (SCCmec IV) have been detected in Brazil and the USA, respectively [5, 20]. In 2012, one VRSA with SCCmec III, spa t037 and pvl negative was reported by Azimian et al, in the northeast of Iran [8]. In another study in Iran, one VRSA isolate harbouring vanA (MIC: 64 µg/ml) was reported by Aligholi, et al. [7]. Therefore, it seems that the incidence of VRSA in Iran is increasing. In the present report, both VRSA isolates belonged to SCCmec III and spa type t030, with a different presence of erm and mrsA/B genes. These findings confirm that these isolates have acquired new resistance genes during persistence in ICU and hospitals. Also, SCCmec III is found predominantly in healthcare-associated MRSA isolates and is transferred by person-to-person spread in the hospital. Since no VRSA strain was observed in the authors’ subsequent epidemiological studies, it seems these isolates have been not transmitted from patient to other patient, or to healthcare workers.

Conclusion

Since a high rate of MRSA isolates has been reported in Iran, finding VRSA isolates is a serious threat for Iranian hospital settings. Therefore, proper infection-control policies, appropriate antimicrobial agents management and improved awareness of healthcare personnel are needed to prevent the emergence and transmission of VRSA isolates in Iran. Due to the importance of VRSA emergence, these cases were reported to the infection control committee of the affected hospital. As no further VRSA was detected during the next year of specimen collection in this study (until May 2016), it can be concluded that the more strict preventive measures taken to control dissemination of resistant strains in the hospital setting were effective.

References

Raineri E, Crema L, De Silvestri A, et al. Meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus control in an intensive care unit: a 10 year analysis. J Hosp Infect. 2007;67(4):308–15.

Tong SY, Davis JS, Eichenberger E, Holland TL, Fowler VG Jr. Staphylococcus aureus infections: epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and management. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2015;28(3):603–61.

Melo-Cristino J, Resina C, Manuel V, Lito L, Ramirez M. First case of infection with vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Europe. Lancet. 2013;382(9888):205.

Loomba PS, Taneja J, Mishra B. Methicillin and Vancomycin resistant S. aureus in hospitalized patients. J Glob Infect Dis. 2010;2(3):275–83.

Limbago BM, Kallen AJ, Zhu W, Eggers P, McDougal LK, Albrecht VS. Report of the 13th vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolate from the United States. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52(3):998–1002.

Hiramatsu K. Vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: a new model of antibiotic resistance. Lancet Infect Dis. 2001;1(3):147–55.

Aligholi M, Emaneini M, Jabalameli F, Shahsavan S, Dabiri H, Sedaght H. Emergence of high-level vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the Imam Khomeini hospital in Tehran. Med Princ Pract. 2008;17:432–4.

Azimian A, Havaei SA, Fazeli H, et al. Genetic characterization of a vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolate from the respiratory tract of a patient in a university hospital in Northeastern Iran. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50(11):3581–5.

Brakstad OG, Aasbakk K, Maeland JA. Detection of Staphylococcus aureus by polymerase chain reaction amplification of the nuc gene. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30(7):1654–60.

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, 25th informational supplement. CLSI document M100-S25. Wayne: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2015.

Fasihi Y, Saffari F, Kandehkar Ghahraman MR, Kalantar-Neyestanaki D. Molecular detection of macrolide and lincosamide resistance genes in clinical methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) isolates from Kerman, Iran. Arch Pediatr Infect Dis. 2017;5(1):e37761.

Nateghian A, Robinson JL, Arjmandi K, et al. Epidemiology of vancomycin-resistant enterococci in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia at two referral centers in Tehran, Iran: a descriptive study. Int J Infect Dis. 2011;15(5):e332–e335.

Lina G, Piémont Y, Godail-Gamot F, et al. Involvement of Panton-Valentine leukocidin-producing Staphylococcus aureus in primary skin infections and pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29(5):1128–32.

Boye K, Bartels MD, Andersen IS, Mølle JA, Westh H. A new multiplex PCR for easy screening of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus SCCmec types I–V. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2007;13(7):725–7.

Mohammadia S, Sekawi Z, Monjezia A, et al. Emergence of SCCmec type III with variable antimicrobial resistance profiles and spa types among methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated from healthcare- and community-acquired infections in the west of Iran. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;25:152–8.

Liu Y, Wang H, Du N, et al. Molecular evidence for spread of two major methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clones with a unique geographic distribution in Chinese hospitals. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53(2):512–8.

Goudarzi M, Fazeli M, Goudarzi H, Azad M, Seyedjavadi SS. Spa typing of Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from clinical specimens of patients with nosocomial infections in Tehran, Iran. Jundishapur J Microbiol. 2016;9(7):e35685.

Shakeri F, Ghaemi EA. New Spa types among MRSA and MSSA Isolates in north of Iran. Adv Microbiol. 2014;4:899–905.

Chen Y, Liu Z, Duo L, et al. Characterization of Staphylococcus aureus from distinct geographic locations in China: an increasing prevalence of Spa-t030 and SCCmec type III. PLOS ONE. 2014;9(4):e96255.

Rossi F, Diaz L, Wollam A, et al. Transferable vancomycin resistance in a community-associated MRSA lineage. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1524–31.

Acknowledgements

We specifically thank Dr. Javid Sadeghi (Department of Microbiology and Virology, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran) and Dr. Mohammad Emaneini (Department of Microbiology, School of Medicine, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran) for providing standard and control positive strains in phenotypic and genotypic methods.

Funding

This work was supported by the Student Research Committee, Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, Iran (Grant Number : IR.KMU.REC.1395.806).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Y. Fasihi, F. Saffari, S. Mansouri, and D. Kalantar-Neyestanaki declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fasihi, Y., Saffari, F., Mansouri, S. et al. The emergence of vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in an intensive care unit in Kerman, Iran. Wien Med Wochenschr 168, 85–88 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10354-017-0562-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10354-017-0562-6

Keywords

- Staphylococcus aureus

- Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)

- Vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (VRSA)

- Staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec)

- Spa type