Abstract

In Ireland, the badger Meles meles L is a reservoir species for Mycobacterium bovis and, as such, contributes to the maintenance of bovine tuberculosis in cattle. A previous estimate of the badger population in the Republic was 200,000 badgers. In the current study, we obtained data on badger numbers from a large-scale badger removal project (the Four-Area project). The removal areas of the Four-Area Project were surrounded by barriers (either water or buffer areas where removals were also conducted) to prevent badger immigration. Within these areas, a grid of 0.25 km2 was created within which we knew the badger numbers and habitat types (based on Corine data). Associations between badger numbers and habitat type were investigated using negative binomial modeling. Extrapolations from the model yielded an estimated badger population in the Republic of approximately 84,000 badgers. The implications of these findings are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The Eurasian badger Meles meles L. is implicated in the transmission and maintenance of bovine tuberculosis (TB) to cattle in Ireland (Eves 1999; Griffin et al. 2005) and in Britain (Krebs et al. 1997; Gallagher and Clifton-Hadley 2000). The problem has undergone substantial research and review efforts (Gormley and Costello 2003; O’Keeffe 2006; Kelly et al. 2007; Corner et al. 2008) and Britain (Godfray et al. 2004; Reynolds 2006; Bourne et al. 2007; King 2007; McDonald et al. 2008). Badgers are protected by law in Ireland, both North and South (Whilde 1993), and are ecologically significant animals for example, as ecosystem engineers (Jones et al. 1994). Determining the population size is quite difficult (Woodroffe et al. 2007; Smith and Cheeseman 2007). Though social, badgers are shy and nocturnal, living much of their lives underground in large setts (burrows). Furthermore, badgers move frequently and such movements appear to have significant consequences at population level (Garnett et al. 2005; Carter et al. 2007; Pope et al. 2007; Dugdale et al. 2007; McDonald et al. 2008). An understanding of the size of the badger population is important to assist in their management including potential vaccination projects (Collins et al. 1994; O’Keeffe 2006; Kelly et al. 2007).

No quantitative information about badger numbers in Ireland was available until the 1990s when two large-scale structured surveys were performed, one in the north by Feore (1995) and one in the south by Smal (1995). Based on these surveys, it was estimated that the total Irish badger population was approximately 250,000 (50,000 in Northern Ireland, 200,000 in the Republic). Two key assumptions in these estimates, based on small-scale badger removal studies (Smal 1995), were that badger group size was 5.9 adults and that such groups were each associated with a main sett. Recently, another survey in Northern Ireland estimated that there were 33,500 badgers there (Reid et al. 2008).

Capture–mark–recapture studies in separate areas in Ireland have all reported lower numbers of badgers. Feore and Montgomery (1999) reported a mean of 2.3 adult badgers per main sett (33 in 14 main setts) in three different habitats in Northern Ireland. This was consistent with findings from an earlier small-scale capture–mark–recapture study in the south in lowland farmland, which reported an average of 3.8 (SD 1.19) badgers per main sett (27 animals in 1990; 19 in 1991) in six main setts in lowland farmland (Sleeman and Mulcahy 2005). Another study by Smal (unpublished) at five sites in the reference areas of the Four-Area Project in spring 2002 found a total of 87 badgers in 30 main setts in five habitats, a mean of 2.9 badgers per main sett. Other evidence, from a large-scale removal study in East Offaly, in the Irish midlands, reported about 3.0 adult badgers for every main sett (Eves 1999).

The main objective in this study was to estimate the size of the badger population of the Republic of Ireland. Data were obtained from the Irish Four-Area Project (1997–2002), which sought to clarify the role of badgers in the epidemiology of tuberculosis in cattle in Ireland. In part, this was achieved by removal of badgers from four “removal areas” in rural parts of the Republic of Ireland. The removal areas were separated from matched “reference areas” by rivers or other natural boundaries or buffer areas (Fig. 1; Sleeman et al. 2009). Information about variations in sett type and sett occupancy are also examined.

Materials and methods

Study design

The paired study areas were located in four widely separated regions of the Irish Republic (Cork, Donegal, Kilkenny, and Monaghan), representing a range of agricultural habitat types (Table 1). Where the 1-km squares used by Smal’s survey (1995) fell within each removal area, the numbers of setts found were compared with the findings of the present study (Griffin and Hammond 1997).

Intensive proactive badger removal was conducted in the removal areas, aiming to achieve a low badger density after the first year of the study and attain as complete a removal as possible by the end of the second year. Proactive culling was also conducted in surrounding buffer areas to minimize badger migration into the removal areas. In some places, buffer areas were unnecessary, as there were natural barriers to badger migration, mainly large rivers (Fig. 1). Hence, buffer areas were not standardized across the four areas.

Study areas

Each of the four removal areas is described in Table 1; data on land use are dealt with in Hammond (1996) and locations in Fig. 1. The soils found in the four removal areas (Table 1) represent soils found in 60.9% of the area of Ireland (Gardiner and Ryan 1969; Gardiner and Radford 1980). Badger removal from four areas prior to the study in the years 1992–1997 is described in More (2004). The Monaghan removal area is surrounded on three sides by Northern Ireland (Fig. 1). There has never been systematic badger culling in Northern Ireland (Abernethy et al. 2006), other than an experimental cull in the late 1970s (O’Brien 1980).

Sett surveys

Pretrial surveying for setts began in November 1996, and surveying was continued on between September and May until December 1998 when it was completed in all areas. This was done in winter when vegetation cover was low because of leaf fall. Survey teams were composed of field staff supervised by a veterinary inspector. Staff surveyed in pairs, typically walking on both sides of every hedge (in Ireland, setts are frequently in hedges (Fig. 2)). A field manual (Anon 1996) and training sessions were used to standardize procedures. Cattle herd owners, hunters, and others familiar with the area were contacted in advance about the locations of badger setts.

One herd owner in Co Cork refused permission for a survey of setts on his land. This area was nevertheless included in the habitat data, which did not discriminate as it was from satellite images. Setts were initially recorded on photographs and later transferred to maps. Once a sett was located, other data were recorded. These included details of localized habitat(s) where the sett was; the possibility of access for cattle; the numbers of openings and activity at those openings; signs of badgers including paths, latrines, and hairs; whether there were openings with significant spoil heaps; the greatest distance between two openings; and any signs of illegal interference.

Sett surveys were the recommended method for estimating badger numbers (Macdonald et al. 1998). Resurveying of all setts was done before each period of capture and any additional setts identified. We classified setts into main and other (non-main) setts, which we call outlier setts following Ostler and Roper (1998) on the basis of size and levels of activity. Main setts usually had a large number of openings with conspicuous spoil heaps around them. Such setts were heavily used, with well-worn paths between openings. Main setts were normally in continuous use. Outlier setts on the other hand usually have only one to three openings and tend not have large spoil heaps or well-worn paths.

Badgers

Badger removals were conducted from September to May in each year of study. Precise timing and duration depended on terrain and available resources; each area was subject to culling at intervals of about 2 months. Badgers were captured, under license (issued by the Department of the Environment, Dublin), using a stopped restraint, which is a multistrand steel wire 143 cm long with a stop at 28 cm (see Anon 1996 for details). Laid on badger paths (called “passes” in rural Ireland) near setts, stopped restraints are designed to restrain and hold the badger around the body (abdomen and thorax) but not to choke it. The number of restraints used depended on the operative and between 75% and 89% of main setts were targeted for capture initially by December 1998 due to detected activity, whereas 28–50% of outlier setts were targeted (Griffin et al. 2000). This method is commonly employed to capture badgers in Ireland and is both effective and results in minimal damage to the badgers during capture (Murphy et al. 2006). Captured animals were shot with a 0.22 rifle. Field staff members were trained in the safe and humane use of firearms, specifically in relation to badgers, as well as in the safe handling of dead, and potentially infectious, badgers. At capture, the data recorded included the unique sett identifier, date, the numbers of badgers captured, the unique identifier for each badger, and notes concerning whether there had been any interference with the restraints by people or animals both wild and domestic.

Permission from the landowner to capture was refused at 13 setts (0.6%) out of a total of 2,351, and a single holding where permission for the sett survey was refused in Cork. These areas were included in habitat analysis as these habitat data were from satellite images.

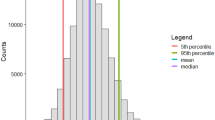

The restraints are designed specifically to catch adult badgers and are unlikely to have been 100% effective. It is well established that some badgers will evade capture (e.g., Tuyttens et al. 2001a). Recent culls in Britain (Smith and Cheeseman 2007) over a short period assumed a capture efficiency of 71–85%. Here, we assumed the higher capture rate of 85%, as our study was over a longer period and included all the animals, either captured or occurring as road casualties, in the first 2 years of the study. Given the 2 years’ efforts of our study, this removal capture rate seems reasonable, given the low percentage caught later (Fig. 3b) combined with the acknowledged efficiency of restraints if used by trained staff (Cheeseman and Mallison 1979). We assume that badger densities per habitat type that are predicted by the model are the same across the Republic of Ireland. We assume that each group occurs in a single occupied main sett, plus its associated outlier (non-main) setts.

Restraints were normally left in position for 11 nights (i.e., from Monday of 1 week to the Friday of the next). Restraints were inspected as early as possible every morning. Operations were repeated for a second 11-night period if badger activity continued. The locations of all restraints were recorded, and all deployments and recoveries of restraints were counted and checked. In the reference areas, badger removals were undertaken solely in response to significant TB outbreaks (Griffin et al. 2005).

Each badger captured, or found as a road casualty, underwent a gross post-mortem examination at either the Central or Regional Veterinary Research Laboratories or at the Irish Equine Center. Badgers found as road casualties were not used in modeling as they could have been from outside the area. The position of the restraint, the presence of any visible skin damage, gender, age, and weight of the badger were recorded (Corner et al. 2008). Methods of aging were standard tooth wear and weight used together (Neal and Cheeseman 1996—“Appendix 2”).

Habitat data for badger population model

Following the methods used by Hammond et al. (2001), computerized grids (forming squares known as micro-tiles) of 0.25 km2 were constructed across each of the four removal areas. Corine habitat codes (Corine land cover 2000-satellite-generated) were used to code the type of habitat within the micro-tiles and the area (km2) of each type was calculated.

Modeling

A negative binomial model was developed to model factors affecting the numbers of badgers. per micro-tile. The independent variables included the total area (km2) of each habitat type within the micro-tile. Each of the habitat variables was initially screened based on a univariable negative binomial model; variables with p < 0.2 became candidates for the multivariable model.

A backward selection process was used to remove terms from the multivariable model, based on a cutoff value of p ≤ 0.05. Following this, we tested the terms that were excluded at the initial screening stage for inclusion in the final model. The modeling was carried out using STATA version 10 (STATA® version10, STATA Corp., College Station TX, USA). Cases that were influential on the final model were investigated by examining Cook’s distances. Models were refit excluding influential cases and differences in the models were examined.

Two models were developed; the first included micro-tiles that were fully within the removal areas and the second included all micro-tiles.

Spatial clustering could result in badger numbers that were more variable than assumed by a simple negative binomial model. Thus, spatial correlation was examined using the method of Hammond et al. (2001). A mixed model was developed using the MIXED procedure in SAS v 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., 2003) with the spatial option. Spatial correlation was assumed to depend on the distance between two midpoints of the micro-tiles; this was represented in the model using the exponential spatial correlation function.

Results

Badger numbers

Table 2 shows data for 1,099 badgers removed from the four removal areas (mean 1.1 badgers per square kilometer) in 1997–1999; 73.2% of badgers were caught at main setts and 26.8% at outlier setts.

Figure 3a shows the number of badgers removed in each removal area during the course of the study and Fig. 3b displays the results as proportions. Badgers captured annually after the initial year’s removal averaged 25.3% of the initial removal number and did not differ significantly over the years (Fig. 3b).

Most badgers caught were adults or yearlings; only ten cubs were captured, all in the first year (Table 3). Only 25 yearlings were recorded in the second year, suggesting that reproductive success was poor in the first year, probably due to disturbance caused by the study. In these years, there was an excess of female badgers (Corner et al. 2008).

Setts

A total of 4,799 setts were found in the removal and reference areas (Table 4). The majority, 3,816, were outliers; far fewer (n = 983) were main setts (20.5% of total). The setts were mainly in field boundaries.

Table 5 displays an analysis of sett structure (in terms of number of openings per sett) for removal and reference areas. Main setts exhibited high variability in number of openings (1–60), though mean numbers were quite consistent (9.6 in removal areas, 8.9 in reference areas).

The numbers of setts found in this study can be compared with the numbers found by the study of Smal (1995). There were 16 1-km squares that were common to both studies. In these, Smal (1995) reported 40 setts; our study found 36, which indicates that sett finding rates were approximately similar; however, there was local variation in sett locations between the two studies. In the Four-Area study, a few extra setts were found after the initial year, these (predominantly outliers) totaled 48 setts. Since the initial survey found 2,351 setts, we can be confident that the initial survey identified 98% of all setts.

The most common localized habitat for setts was field boundaries; 59% of outlier setts and 51% of main setts were found in such habitat. For main setts, a quite common double-habitat location was that of contiguous pasture and field boundary (192; 17% of main setts).

Badgers at setts

Table 6 combines removed badger numbers and sett numbers for the four areas.

Table 6 shows the proportion of main setts at which no badgers were caught in 1997/1998 (the first year of the study) and therefore presumed empty (mean 40.9%). Using occupied main setts gives mean group size of 3.9.

Negative binomial model results

Habitat variables included in the model are shown in Table 7 and the number of badgers and area size associated with each habitat are included in Table 8.

The final models varied depending on whether data were drawn from all micro-tiles (Table 9) or a model based on using only micro-tiles completely within the removal areas (Table 10). From the model based on micro-tiles completely within the removal area, the number of badgers per micro-tile was inversely related to the area of “Moors and heathland” and areas of “Blanket bog” habitats. Outliers from the model were examined using Cook’s distances. Removal of the tiles with the largest Cooks values resulted in very little change in the final model. The model based on all micro-tiles produced (Table 9) predictions that were much larger than observed numbers (21,442 predicted versus 1,099 observed) and had very wide confidence limits. Thus, this model was not utilized.

Spatial correlations in the final model

Based on the model that included only micro-tiles that were fully within the removal areas, the correlation between badger numbers in neighboring micro-tiles was not significant (p = 0.751).

The predicted number of badgers for each county was calculated using only micro-tiles completely within the removal area and results are presented in Table 11. The county predictions are based on models built by excluding data for the predicted county. The confidence intervals (CI) of the predicted numbers of badgers for all counties included the observed number of badgers.

Predicted number of badgers in the Republic of Ireland

At the time of the study, the area of “Moors and heathland” (habitat 322) in the Republic of Ireland was 590 km2; the area of “Blanket bog” (habitat 4122; Tables 2 and 3) was 9,239 km2 and the remaining land area was 61,281 km2. Based on the previous parameter estimates (Table 11), the estimated number of badgers within the Republic of Ireland would be 71,000 (95% CI 61,000 to 81,000). If we assume the capture rate was at least 85% effective (see “Materials and methods”), the estimated numbers of badgers in the Republic of Ireland becomes to 84,000 (95% CI 72,000 to 95,000).

Discussion

This study confirmed that badgers are common and widespread in agricultural habitats across the Republic of Ireland but showed that the animals may not be as numerous as the last estimate (Smal 1995; 200,000) had suggested. Historically, badgers were scarce. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, they were reported to have increased between the 1890s and the 1970s (Millais 1904; Barrington 1926; Moffat 1938; Fairley 1984). As discussed later, there are reasons to think this increase has slowed or stopped. The numbers of badgers per sett did not show great variation across the four areas. The group size (four to five adults) is close to the continental European norm of approximately four (Kowalczyk et al. 2003).

The spatial correlation calculations were crude, because one of the main assumptions (as required when using a mixed model) is that the data are normally distributed. However, Hammond et al. (2001) found similar results relating to spatial correlation. They also looked at correlations between grids further apart and found badger numbers only became correlated with those of neighboring grids when the grid size reached 1.5 km2 (per side).

Hammond et al. (2001) found that high-quality pasture habitats were associated with increased badger numbers. Using data from the British randomized badger culling trial, Durr (2004) looked at sett density inside 1-km2 quadrants in nine of the treatment areas and found that sett numbers were positively associated with broad-leaved woodland, silty soils, and improved grasslands. Water-holding soils were negative predictors. Using data collected from the two national surveys in Britain, Newton-Cross et al. (2007) also found a negative relationship between setts and heather moorland, as well as a positive association of sett numbers with grassland and woodland. The scarcity of setts in bog and moorlands has been found in other Irish surveys (Smal 1995; Feore 1995).

The estimate of the number of badgers in the Republic of Ireland, from 72,000 to 95,000, is less than half that suggested by previous studies (Smal 1995). We regard our estimate as robust because of the geographical diversity of the study, the intensity of investigation, and particularly because of the use of barriers (natural and in the form of buffers) to minimize inflated estimates caused by migration of badgers and we only used 2 years’ data. In earlier smaller-scale removal studies (e.g., Smal 1995, pp 129–191), badgers were probably caught while visiting setts that had been depopulated by removals. Further studies are in progress, which will in the short term bring further precision to such estimates in both the north and south of Ireland.

Recently developed techniques such as estimating badger densities by quantifying latrine use (Tuyttens et al. 2001b), distance sampling (Hounsome et al. 2005), or by genetic analysis from badger droppings or hairs (Wilson et al. 2003; Frantz et al. 2004) might be usefully employed, perhaps together with field sett surveys, to get better estimates of the badger population in the Republic of Ireland. Comparative studies using non-invasive genotyping and field surveys, such as the study by Arrendal et al. (2007), would give further reliability to estimates.

There is evidence from field studies that badgers frequently visit and often take over neighboring main setts (Sleeman 1992; O’Corry-Crowe et al. 1993; Christian 1995; Feore and Montgomery 1999). In all removal studies, the capture of immigrating animals is well known to inflate population estimates (Glasgow 1953; Sutherland 1996; Southwood and Henderson 2000). Such overestimates are known to have occurred in removal studies of badgers (O’Corry-Crowe et al. 1993; McGrath 2001) and other Irish mammals in Ireland (Ellenbroek 1980; Smal 1991). Both in Ireland and Britain, badgers have been reported to sometimes move in groups (sometimes called coalitions; Sleeman 1992; Roper et al. 2003), which may exacerbate overestimation errors.

Another reason for the lower estimate lies in the high proportion of unoccupied main setts. The finding that about 41% of badger main setts were unoccupied by badgers at the start of the study (i.e., prior to removals) was consistent across the four areas (Table 10). This is common in Ireland. As one example, work done in west Cork in the late 1980s and early 1990s showed that only a third of all setts was active at any one time (McCarthy 1993). The high number of deserted setts suggests a decline in the Irish badger population. Road traffic accidents are the major cause of death for badgers in Ireland, as in Britain. Smal (1995) reported more unoccupied setts in the east of the Republic, which is extensively developed with consequently more vehicles and greater risks of road traffic to badgers. This risk would have increased from the 1970s onwards but particularly in the 1990s “Celtic Tiger” period, when vehicle numbers increased rapidly.

Setts in Ireland, especially deserted setts, are reported to be often occupied by other animals such as rabbits Oryctolagus cuniculus, foxes Vulpes vulpes, and, less frequently, mainly on coasts, by otters Lutra lutra (Smal 1995; Sleeman and Smiddy 1999). Main setts are substantial and complex and can endure for more than a century (Fairley 2001), even though life span of an individual badger is no greater than a decade (Il-Fituri and Hayden 1993). Whether a particular badger sett remains occupied is presumably contingent on dispersal patterns, changes in food availability, disease, and removal intensity over time.

From the perspective of bovine tuberculosis control, the lower estimated Irish badger population indicates that the scale of the management problem is less than previously recognized. Certain tasks like reduction and/or vaccination of the badger population (Hughes et al. 1996; Gormley and Collins 2002; Gormley and Costello 2003; Delahay et al. 2003; Abernethy et al. 2006; O’Keeffe 2006; Hone and Donnelly 2008) may be more readily accomplished than formerly expected or at least have lower target populations. On the other hand, since the badger is a protected species, there are implications for designing removal studies that do not threaten the species’ long-term sustainability.

In general, this study identified more openings at individual setts (Table 4) than reported by other Irish studies. Feore (1995) and Reid et al. (2008) in Northern Ireland and Smal (1995) in the Republic found for example a mean of 6.8, 7, and 6.9 openings per main sett, respectively, whereas in our study we found a mean of 9.6 openings per main sett in removal areas and 8.9 in reference areas. All of these values are lower then than those found in Britain for example by Cresswell et al. (1990) who reported 11.9 openings in active main setts. However, the finding of main setts with up to 60 openings (in Monaghan) reaffirms the complexity of setts, which reflects the cumulative efforts of generations of badgers. Setts in Britain tend to be bigger, as they are often in woods and are not restricted, compared with most Irish setts, which are mostly constrained by their location at field boundaries.

The calculated group size in the removal areas was close to 3.9 animals (Table 6), less than the value of 5.9 used by Smal (1995) but greater than that of 3.0 derived by Eves (1999) in East Offaly. For models developed in Britain, it has been suggested that at least six to eight badgers, yearling and adults, are needed in a badger group for tuberculosis to be sustained (White and Harris 1995; Smith et al. 1995, 2001). However, it seems clear that these models do not apply in Ireland, where fewer animals is the norm, yet tuberculosis still persists.

References

Abernethy DA, Denny GO, Menzies FD, McGuckian P, Honhold N, Roberts AR (2006) The Northern Ireland programme for the control and eradication of Mycobacterium bovis. Vet Microbiol 112:231–237. doi:10.1016/j.vetmic.2005.11.023

Anon (1996) Badger manual. Department of Agriculture, Food and Forestry, Dublin

Arrendal J, Vila C, Björklund M (2007) Reliability of noninvasive genetic census of otters compared to field censuses. Conserv Genet 8:1566–1585. doi:10.1007/s10592-006-9266-y

Barrington JS (1926) Increase of the badger. Ir Nat J 1:168

Bourne J, Donnelly C, Cox D, Gettinby G, Morrison I, Woodroffe R (2007) Bovine TB: the scientific evidence, final report to the Rt Hon David Miliband MP. Ministry of Agriculture, London

Carter SP, Delahay RJ, Smith GC, Macdonald DW, Riordan P, Etherington TR, Pimley ER, Walker NJ, Cheeseman CL (2007) Culling-induced social perturbation in Eurasian badgers Meles meles and the management of TB in cattle: an analysis of a critical problem in applied ecology. Proc R Soc 274B:2759–2777

Cheeseman CL, Mallison PJ (1979) Radio tracking in the study of bovine tuberculosis in badgers. In: Amlaner CI, Macdonald DW (eds) A handbook on biotelemetry and radio-tracking. Pergamon, Oxford, pp 646–656

Christian SF (1995) Observations of extra-group mating and mate-defence behaviour in badgers, Meles meles. J Zool (Lond) 237:668–670

Collins JD, Ellis W, Feore M, Mulcahy MF, Neil S, Sheridan M, Sleeman DP, Hughes S, Rogers M (1994) The feasibility of developing a vaccine against tuberculosis for use in the badger (Meles meles), report of a steering committee. Department of Agriculture, Food & Forestry Dublin/Department of Agriculture for Northern Ireland, Belfast

Corner LAL, Clegg TA, More SJ, Williams DH, O’Boyle I, Costello E, Sleeman DP, Griffin JM (2008) The effect of varying levels of population control on the prevalence of tuberculosis in badgers in Ireland. Res Vet Sci 85:238–249. doi:10.1016/j.rvsc.2007.11.010

Cresswell P, Harris S, Jefferies DJ (1990) The history, distribution, status and habitat requirements of the badger in Britain. Nature Conservancy Council, Peterborough

Delahay RJ, Wilson GJ, Smith GC, Cheeseman CL (2003) Vaccinating badgers (Meles meles) against Mycobacterium bovis: the ecological considerations. Vet J 166:43–51. doi:10.1016/S1090-0233(03)00071-6

Dugdale HL, Macdonald DW, Pope LC, Burke T (2007) Polygynandry, extra group paternity and multiple-paternity litters in European badger (Meles meles) social groups. Mol Ecol 16:5294–5306

Durr PA (2004) In: Durr PA, Gattrell AC (eds) Spatial epidemiology and animal disease: introduction and overview. GIS and spatial analysis in veterinary science. CABI, Wallingford, pp 35–67

Ellenbroek FJM (1980) Interspecific competition in the shrews Sorex araneus and Sorex minutus (Soricidae, Insectivora): a population study of the Irish pygmy shrew. J Zool 192:119–136

Eves JA (1999) Impact of badger removal on bovine tuberculosis in east County Offaly. Ir Vet J 52:229–236

Fairley JS (1984) An Irish beast book. Blackstaff, Belfast

Fairley JS (2001) A basket of weasels. James Fairley, Belfast

Feore SM (1995) The distribution and abundance of the badger Meles meles L. in Northern Ireland. Ph.D. thesis, Queen’s University, Belfast

Feore SM, Montgomery WI (1999) Habitat effects on the spatial ecology of the European badger (Meles meles). J Zool (Lond) 247:537–549. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1999.tb01015.x

Frantz AC, Schaul M, Pope LC, Fack F, Schley L, Muller CP, Roper TJ (2004) Estimating population size by genotyping remotely plucked hair: the Eurasian badger. J Appl Ecol 41:985–995. doi:10.1111/j.0021-8901.2004.00951.x

Gallagher J, Clifton-Hadley RS (2000) Tuberculosis in badgers; a review of the disease and its significance for other animals. Res Vet Sci 69:203–217. doi:10.1053/rvsc.2000.0422

Gardiner MJ, Ryan P (1969) A new generalized soil map of Ireland and its land-use interpretation. Ir. J Agric Res 8:95–109

Gardiner MJ, Radford T (1980) Ireland: general soil map. , 2nd edn. Teagasc, Dublin

Garnett BT, Delahay RJ, Roper TJ (2005) Ranging behaviour of European badger (Meles meles) in relation to bovine tuberculosis (Mycobacterium bovis). Appl Anim Behav Sci 94:331–340. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2005.02.013

Glasgow JP (1953) The extermination of animal populations by artificial predation and estimation of populations. J Anim Ecol 22:32–46. doi:10.2307/1688

Godfray HCJ, Curnow RN, Dye C, Pfeiffer D, Sutherland WJ, Woolhouse MEJ (2004) Independent scientific review of the Randomised Badger Culling Trial and associated epidemiological research. http://www.defra.gov.uk/animalh/tb/default.htm

Gormley E, Collins JD (2002) The development of wildlife control strategies for eradication of tuberculosis in cattle in Ireland. Tuber Lung Dis 80:229–236. doi:10.1054/tuld.2000.0250

Gormley E, Costello E (2003) Tuberculosis and badgers: new approaches to diagnosis and control. J Appl Microbiol 94:80–86. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2672.94.s1.9.x

Griffin JM, Hammond RF (1997) A field trial to evaluate the contribution of infected badgers to the prevalence of bovine tuberculosis in the Republic of Ireland and variables used to characterise the badger removal/reference areas based on the East Offaly badger removal project. Tuberculosis Investigation Unit, University College, Dublin

Griffin JM, Hammond RF, Towey KP, McGrath G, Sleeman DP, Costello E (2000) The four-area badger study: a progress report, 1996–1999. In: Collins JD, Hammond RF (eds) Selected papers 1999, Tuberculosis Investigation Unit. University College, Dublin

Griffin JM, Williams DH, Kelly GE, Clegg TA, O’Boyle I, Collins JD, More SJ (2005) The impact of badger removal on the control of tuberculosis in cattle herds in Ireland. Prev Vet Med 67:237–266. doi:10.1016/j.prevetmed.2004.10.009

Hammond R (1996) Variables used to characterize the four area badger removal/reference areas. In Selected Papers Tuberculosis Investigation Unit. University College, Dublin, pp 12–18

Hammond R, McGrath G, Martin SW (2001) Irish soil and land use classifications as predictors of numbers of badgers and badger setts. Prev Vet Med 57:137–148. doi:10.1016/S0167-5877(01)00230-6

Hone J, Donnelly CA (2008) Evaluating evidence of association of bovine tuberculosis in cattle and badgers. J Appl Ecol 45:1160–1666. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2664.2008.01476.x

Hounsome TD, Young RP, Davidson J, Trewby ID, Yarnell RW, Garnett B, Delahay RJ, Wilson GJ (2005) Estimating badger abundance by distance sampling: an evaluation study on a intensively studied, high density population. J Zool (Lond) 266:81–87. doi:10.1017/S0952836905006606

Hughes MS, Neill S, Rogers MS (1996) Vaccination of the badger (Meles meles) against Mycobacterium bovis. Vet Microbiol 51:363–379. doi:10.1016/0378-1135(96)00051-X

Il-Fituri AI, Hayden TJ (1993) Craniometrics and age determination of the Eurasian badger. In: Hayden TJ (ed) The badger. Royal Irish Academy, Dublin, pp 58–63

Jones CG, Lawton TH, Shachak M (1994) Organisms as ecosystem engineers. Oikos 69:373–386. doi:10.2307/3545850

Kelly GE, Condon J, More SJ, Dolan L, Higgins I, Eves J (2007) A long-term observational study of the impact of badger removal on herd restrictions due to bovine TB in the Irish midlands during 1989–2004. Epidemiol Infect 136:1362–1373

King D (2007) Bovine tuberculosis in cattle and badgers, a report by the chief scientific advisor, Sir David King. Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, London

Kowalczyk R, Zalewski A, Jędrzejewska B, Jędrzejewsk W (2003) Spatial organization and demography of badgers (Meles meles) in Bialowież Primeval Forest (eastern Poland) compared with other Palearctic populations. J Biogeogr 30:463–472

Krebs J, Anderson R, Clutton-Brock T, Morrison I, Young D, Donnelly C (1997) Bovine tuberculosis in cattle and badgers. Report to Rt Hon Dr J. Cunningham M P. HMSO, London

Macdonald DW, Mace G, Rushton S (1998) Proposals for future monitoring of British mammals. Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions, HMSO, London

McCarthy J (1993) The badger vaccination trial in west Cork: a progress report. In: Hayden TJ (ed) The badger. Royal Irish Academy, Dublin, pp 181–188

McDonald RA, Delahay RJ, Carter SP, Smith GP, Cheeseman CL (2008) Perturbing implications of wildlife ecology for disease control. Trends Ecol Evol 23:53–56. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2007.10.011

McGrath G (2001) An evaluation of the role of geographical information system technology for the prediction of badger sett location in Ireland. Unpublished, M.Sc. thesis, Trinity College, Dublin

Millais JG (1904) The mammals of Great Britain and Ireland. Longmans Green, London

Moffat CB (1938) The mammals of Ireland. Proc R Ir Acad [B] 44B:61–128

More S (2004) The impact of badger removal on the control of tuberculosis in cattle herds in Ireland. A Report prepared for the Minister of Agriculture and Food, Dublin

Murphy D, O’Keeffe JJ, Corner LAL (2006) An assessment of injury to badgers due to capture in stopped restraints. In: More SJ (ed) Biennial report, 2004–05. Centre for Veterinary Epidemiology and Risk Analysis/ The TB Diagnostics and Immunology Research Centre/ The Badger Vaccine Project. University College, Dublin, pp 95–100

Neal E, Cheeseman C (1996) Badgers. T & AD Poyser, London

Newton-Cross G, White P, Harris S (2007) Modelling the distribution of badgers Meles meles: comparing predictions from field based and remotely derived habitat data. Mammal Rev 37:54–70. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2907.2007.00103.x

O’Brien JJ (1980) Badgers and bovine tuberculosis in Northern Ireland. In Nature Conservation and Agriculture. New University of Ulster, Coleraine, pp 1–6

O’Corry-Crowe G, Eves J, Hayden TJF (1993) Sett distribution, territory size and population density of badgers (Meles meles L.) in east Offaly. In: Hayden TJ (ed) The badger. Royal Irish Academy, Dublin, pp 35–56

O’Keeffe JJ (2006) Description of a medium term strategy toward eradication of tuberculosis in cattle in Ireland. In: Costello E, Kenny K (eds) Veterinary network of laboratories researching into improved diagnosis and epidemiology of mycobacterial diseases. Central Veterinary Laboratory Department of Agriculture and Food, Dublin, pp 2–9

Ostler JA, Roper T (1998) Changes in size, status and distribution of badger Meles meles L. setts during a 20-year period. Z Saugetierkd 63:200–209

Pope LC, Butlin RK, Wilson GJ, Woodroffe R, Ervan K, Conyers CM, Franklin T, Delahay RJ, Cheeseman CL, Burke T (2007) Genetic evidence that culling increases badger movement: implications for the spread of bovine tuberculosis. Mol Ecol 16:4919–4929. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03553.x

Reid N, Etherington TR, Wilson G, McDonald RA, Montgomery WI (2008) Badger survey of Northern Ireland 2007/08. Report prepared by Quercus and Central Science Laboratory for the Department of Agriculture & Rural Development (DARD), Northern Ireland, UK

Reynolds D (2006) A review of tuberculosis science and policy in Great Britain. Vet Microbiol 112:119–126. doi:10.1016/j.vetmic.2005.11.042

Roper TJ, Osler JR, Conradt L (2003) The process of dispersal in badgers Meles meles. Mammal Rev 33:314–318. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2907.2003.00031.x

Sleeman DP (1992) Long-distance movements in an Irish badger population. In: Priede IG, Swift SM (eds) Wildlife telemetry. Ellis Horwood, Chichester, pp 670–676

Sleeman DP, Mulcahy MF (2005) Loss of territoriality in a local badger Meles meles population at Kilmurry, Co. Cork, Ireland. Ir Nat J 28:11–19

Sleeman DP, Smiddy P (1999) Records of otters (Lutra lutra) in the vicinity of Irish badger setts. Bull Ir Biogeogr Soc 23:92–97

Sleeman DP, Davenport J, More S, Clegg TA, Griffin JM, O’Boyle I (2009) The effectiveness of barriers to badger Meles meles immigration in the Irish Four Area project. Eur J Wildl Res (in press)

Smal C (1991) Feral mink in Ireland. Wildlife Service, Dublin

Smal C (1995) The badger and habitat survey. Government Publications, Dublin

Smith GC, Cheeseman CL (2007) The efficacy of trapping during the initial proactive culls in the randomized badger culling trail. Vet Rec 160:723–726

Smith GC, Richards MS, Clifton-Hadley RS, Cheeseman CL (1995) Modelling bovine tuberculosis in badgers in England: preliminary results. Mammalia 59:639–650

Smith GC, Cheeseman CL, Wilkinson D, Clifton-Hadley RS (2001) A model of bovine tuberculosis in the badger Meles meles: the inclusion of cattle and the use of a live test. J Appl Ecol 38:520–535. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2664.2001.00610.x

Southwood TRE, Henderson PA (2000) Ecological methods. Blackwell Science, Oxford

Sutherland WJ (1996) Ecological census techniques. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Tuyttens FAM, Macdonald DW, Delahay R, Rogers LM, Mallinson PJ, Donnelly CA, Newman C (2001a) Differences in trappability of European badgers Meles meles in three populations in England. J Appl Ecol 36:1051–1062. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2664.1999.00462.x

Tuyttens FAM, Long B, Fawcett T, Skinner A, Brown JA, Cheeseman CL, Roddam AW, Macdonald DW (2001b) Estimating group size and population density of Eurasian badgers Meles meles by quantifying latrine use. J Appl Ecol 38:1114–1121. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2664.2001.00665.x

Whilde A (1993) Threatened mammals birds, amphibians and fish in Ireland. Irish red data book 2: Vertebrates. HMSO, Belfast

White PCL, Harris S (1995) Bovine tuberculosis in badger (Meles meles) populations in southwest England: the use of spatial stochastic simulation model to understand the dynamics of the disease. Philos Trans R Soc 349:391–413. doi:10.1098/rstb.1995.0126

Wilson GJ, Frantz AC, Pope LC, Roper T, Burke T, Cheeseman CL, Delahay RJ (2003) Faecal DNA profiling to estimate badger numbers. J Appl Ecol 40:658–666. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2664.2003.00835.x

Woodroffe R, Gilks P, Johnston WT, LeFevre AM, Cox DR, Donnelly CA, Bourne FJ, Cheeseman CL, Gettinby G, McInerney JP, Morrison WI (2007) Effects of culling on badger abundance: implications for tuberculosis control. J Zool (Lond) 273:1–10. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2007.00295.x

Acknowledgements

This investigation was part of a large and complex study funded by the Department of Agriculture and Food. We thank all those who took part in the project especially Daniel M. Collins and others at the Center for Veterinary Epidemiology and Risk Analysis, University College, Dublin. Bovine tuberculosis has been a major problem in rural Ireland for a long time and the herd owners, recognizing this, were especially helpful. The project would not have succeeded save for efforts by a large number of field and administrative staff of the Central or Regional Veterinary Research Laboratories and the Irish Equine Center. We also wish to thank Leigh Corner, Eamonn Gormley, Anthony Fitzgerald, Guy McGrath, and John Wilson for helpful input. The methods used in this investigation comply with current laws in the Republic of Ireland.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by C. Gortázar

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sleeman, D.P., Davenport, J., More, S.J. et al. How many Eurasian badgers Meles meles L. are there in the Republic of Ireland?. Eur J Wildl Res 55, 333–344 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10344-008-0244-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10344-008-0244-1