Abstract

One major result of forest conversion in Saxony, East Germany, is the increasing importance of two-storied stands composed of a conifer canopy and a deciduous-tree understory. To enhance the applicability of the growth and yield simulator BWINPro under these conditions, three of its major sub-models were adapted to the regional growing conditions and to the relatively high level of diversity in spatial structure, mixture of species, and age variability typical for forests in conversion: (1) A new module for simulating single-tree juvenile growth was developed for European beech and Common oak under canopies of Norway spruce and Scots pine. Predictions in this sub-model are derived from individual height, diameter at breast height (dbh), and the influences of horizontal and vertical competition; (2) An alternative distance-dependent competition index was introduced to estimate individual basal area increment according to tree-specific growing conditions; (3) A modified logistic mortality model was parameterized for the most important Saxon species based on tree dimensions and basal area increment. Data came from permanent sample plots distributed throughout the region and from three chronosequence plot series established specifically for obtaining model input data. The new components were included into the existing structure of BWINPro. As a result of the adaption, the regional version BWINPro-S provides enhanced opportunities of planning and management for forest conversion and for multi-storied stands.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Forest conversion has been a major objective for planning and management in Germany for more than two decades. The planting of broadleaved tree species such as European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.)Footnote 1 and Common oak [Quercus petraea (Matt.) Liebl. and Quercus robur L.] under conifer canopies has been one of the most effective and common measures to reduce the biotic and abiotic risks associated with pure and even-aged stands of Norway spruce [Picea abies (L.) Karst.] and Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.). The State of Saxony in the southern part of East Germany is an exemplary region both for the problems related to monoculture conifer forestry and for the extensive efforts to address them (Thomasius 1992; Spiecker 2000; Spiecker et al. 2004).

As a result of widespread conversion activities, the importance of multi-storied stands in forestry practice has increased steadily in Saxony and in other parts of Germany during the past decades. However, the applicability of traditional yield tables and other simple, stand-oriented models in these stands is limited by intra- and inter-specific competition, diversity in spatial structure, age and species composition, and the resulting variety of growth patterns. A number of simulation programs have been developed recently to close this information gap (Hasenauer 1994; Nagel 1999; Pretzsch 2001; Porté and Bartelink 2002; Landsberg 2003; Vanclay 2003). According to Peng (2000), most of these programs can be classified as empirical models based upon a set of regression equations to predict basic growth variables. Reliable estimates depend on the size, diversity, and regional significance of their database, particularly in the context of forests in conversion and/or under continuous cover management (Pretzsch et al. 2002; Pommerening and Murphy 2004).

This dependence on regional data and the particular growing conditions in mixed-species forests have been major factors influencing the development of a single-tree, competition-sensitive simulation model based on the program BWINPro for Saxony’s forests. A research project was set up in 1999 to provide forest managers with decision-support tools capable of simulating tree and stand development under the influence of forest conversion activities and the resulting stand structures. Studies were conducted at Dresden University of Technology in close co-operation with the State Forest Administration of Saxony and the Forest Research Station of Lower Saxony in Göttingen. The simulator BWINPro was chosen because of its modular structure, its free availability, and the relatively simple regression models at the core of the program. The central task was to adapt this program to the growing conditions in Saxony and to extend it for greater flexibility. The scope of adaption and integration of new elements is going to be demonstrated by the following three examples representing crucial stages in the life cycle of trees and stands:

-

1.

A new sub-model for single-tree juvenile growth of beech and oak under canopies of spruce and pine (as a general rule throughout the program, a threshold height of 15 m was established within the relevant model routines to separate “juvenile” growth from the following “adult” phase).

-

2.

An alternative distance-dependent competition index for the estimation of individual basal area increment in the adult phase.

-

3.

A modified mortality model for the most important Saxon species based on tree dimensions and basal area increment.

The objectives of this paper are (1) to demonstrate the general approach of adaption and enhancement of an existing program, (2) to explain the sub-models and algorithms underlying three selected additional modules, and (3) to show potential users the benefits achieved by regionalizing the database and by upgrading relevant program elements.

Material

The simulator BWINPro 6.0: model description

BWINPro is a single-tree oriented modular computer program for analyses and prognoses of forest growth and yield in pure and mixed stands. Its development started in the 1990s at the Forest Research Station of Lower Saxony in Göttingen. Inherent growth models have been calibrated for all relevant tree species and all major forest sites in Northwest Germany (Nagel 1999). Estimations of tree growth are based on predictions of basal area increment by a regression model using crown surface area, age, a competition index, and an indicator for release effects as independent variables (Wykoff et al. 1982). The distance-independent competition index C66 in BWINPro is a modified version of the index described by Wensel et al. (1987) and represents the social position of a tree. The C66 of a subject tree is calculated by summing up the horizontal crown areas of all trees cut at the height of its greatest crown width, which is fixed at 66.6% of crown length from the top (Nagel 1999). The difference in C66 values before and after thinning transfers the effect of increased resource availability for released trees into increment estimation. Individual height increment is derived from age-dependent height curves modified by the current height-to-age relation and stand top height. The height-to-age ratio (as indicator for site productivity) is the basis of self-calibrating procedures, which directly influence tree development in the program. Crown width is calculated by a non-linear model based on diameter at breast height (dbh); height of crown base depends on height, dbh, and stand top height. Except for the new routines modeling juvenile growth, most model functions directly estimate dependent variables instead of using a potential-modifier approach common in other models (Pretzsch 2001). While most initial calibration data came from even-aged stands, current research on BWINPro rests on a much larger data base covering multi-storied and mixed stands, thus enhancing the applicability of the simulator for a wider range of stand types and thinning regimes (Schmidt 2001; Nagel et al. 2002; Schröder 2004; Nagel and Schmidt 2006).

Data

The data for regional calibration of BWINPro and for developing its new components represent site and climatic conditions that are typical for two major regions of Saxony: the lowlands in the northwest, and the Ore Mountains in the south of the state. Forests in the lowland region are dominated by Scots pine; annual precipitation is 550–650 mm and mean temperature 8–9°C. The geological situation is characterized by ground and terminal moraines as well as Pleistocenic sands. In the Ore Mountains, pure Norway spruce stands occupy more than 80% of the total forest area which is located mainly at altitudes from 300–800 m a.s.l. Annual precipitation ranges from 710 to 1200 mm and mean temperature from 4 to 8°C. Soil conditions vary from dystric and spodi-dystric cambisols to leptic and orthic podzols, mostly originating from old Paleozoic rocks like granite, porphyry, and gneiss (Fürst et al. 2004).

A trial plot database was used for calibration, which is maintained at the Chair of Forest Growth Science in Tharandt, Saxony (Röhle 1999). It contains a large number of frequently monitored plots for the most important tree species in Saxony. In addition, three new series of trial plots were established in 2001 in two-layered forest-conversion stands composed of the above-mentioned species. They were used to improve the insufficient data basis for estimating juvenile growth, to obtain first-hand information on competition and increment in forest conversion stands, and to collect additional spatially explicit data for the relevant species. The new plots were set up in a chronosequential order (i.e., as unreal time series). They comprise (1) a series of four pine-beech and (2) a series of three pine-oak mixed stands both in the forest district of Falkenberg, Northwest Saxony, and (3) a series of four spruce-beech mixed stands in the forest district of Heinzebank in the central Ore Mountains (Röhle 2001). The chosen stands roughly represent the three age stages of 10, 20, and 40 years in the understory and 60–105 years in the overstory. Around all plots a strip of 12-15 m was established as a buffer zone where only canopy tree data were recorded (Schröder 2004). The spruce-beech and the pine-beech chronosequences together comprise eight plots of 0.25 ha each. The 11 plots in the oak-pine series were complemented by 23 sample plots in two mixed stands of pine (100 years old) and oak (40–60 years old) sown by European jay (Garrulus glandarius L.; Börner and Eisenhauer 2003). Each plot contains only two relevant species (conifers in the overstory, broadleaves in the understory). Site classes and soil characteristics of the new chronosequence stands correspond to those of the main areas for conversion activities in Saxony (Fürst et al. 2004). The characteristics of the newly established trial plots (juv.) and information on the data used to calibrate the existing sub-model for adult growth (ad.) are summarized in Table 1.

For calibrating the adult growth model, dbh and position (x/y-coordinates) of all trees were recorded with an average measuring interval for dbh of 5 years. Repeated measurements of tree height, crown radii, and height of crown base were available for most of these plots. On the plots of the chronosequence series, individual dbh, height, crown width, and height of crown base were measured for all trees. Increments in height (vertical distance from base of annual shoot to tip of corresponding terminal bud) of the past 5 years 1996–2001 were recorded for 20–100 sample trees per plot in the understory (average = 45, n = 570). Dbh increments (doubled mean of four radius measurements in the cardinal directions, related to the same period) were measured for sub-samples of 20–45 trees per plot (average = 25, n = 200).

Methods

Juvenile growth model for beech and oak

The data collected on the chronosequence plots were used for detailed analyses of the relations between specific competition situation and individual tree growth. To predict growth from initial status, canopy tree dimensions at the start of the analyzed increment period (1996) were derived from BWINPro’s data completion routines after adapting them to the Saxon data pool. Juvenile tree dimensions were reconstructed by means of regression models of size over age based on the data from all chronosequence plots. The investigations involved geometrical competition indices (CIs) as well as point-related estimations of the available irradiance derived from the computer-aided evaluation of tree-related hemispherical photographs (Wagner 1994). These “fisheye” photos were taken on all plots of the three chronosequences for a sample of 270 trees in the understory whose increment had been measured. For trees below a height of 5 m, the “individual point of view” of a tree was captured by placing the camera closely over its terminal bud. For all other sample trees, photos were taken after felling at heights of 2 and 5 m vertically over the stump. Photo interpretation focused on diffuse site factor (diffsf), sky obscuration factor in a zenith circle with 10°-radius (Z10), and photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) in relation to local cloudiness. For each sample tree, these three variables as well as the geometrical CIs were related to the mean values of annual increment in height, in dbh, and in basal area between 1996 and 2001. Arithmetic means of increments were used because regression functions over time did not differ significantly from a linear type for neither height nor dbh increment of a given age class (first derivative of increment without any significant trend over time).

The juvenile growth sub-model consists of a set of equations related to the development of a central growth variable. This variable was identified by its sensitivity towards competition influences: the more sensitive height or dbh increment reacts to competition, the more suitable it is for modeling purposes in the given context (Röhle et al. 2004). A simple linear model including variables in logarithmic form was chosen for estimating the central variable’s increment in order to allow for future specifications and refinement. Predictor variables were identified based on the biological relations and by assessing their significance in linear regression analyses as well as their availability in practical forest management (Zhao et al. 2004). Parameters were estimated by ordinary-least-squares (OLS) and weighted-least-squares (WLS) linear regression analysis.

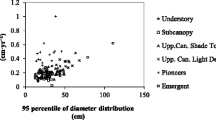

Competition influences on increment of advance-planted trees were quantified by partial correlation analysis in separate investigations of horizontal (within the understory), vertical (influence of the canopy), and total competition (Golser and Hasenauer 1997; Schröder 2004). Analyses involved a number of CIs described in the literature (Hegyi 1974; Biging and Dobbertin 1995; Pretzsch 2001) and a special CI developed to reflect the growing conditions for the understory in two-layered stands (Eq. (1); Schröder 2004). This new CI reflects the shading influence by vertical crown areas (VCA) of competitors (Fig. 1).

where i = subject tree, j = competitors, n = number of competitors; and dist ij = ground distance between i and j.

Possible competitors are chosen for all quantification models by applying a vertical “search” cone with an opening angle of 80° positioned upside down at ground height (for oak) or at the height of crown base (H CB; for beech) of the subject tree (Fig. 1).

After adding the estimated increment of the central variable to its initial value, the resulting value has to be checked against limiting functions, thus creating upper margins for growth in accordance with data recorded for the following adult growth phase. These limiting functions proposed by Golser (1997) facilitate a smooth passage into the functions modeling the adult phase. Individual dbh in beech is derived from allometrical “stand diameter curves” (with parameters changing over age) which reflect height/dbh relations measured on the chronosequence plots. A random component takes into account the natural variation of dbh values for a given tree height. In oak, the parameters of stand height curves after Michailoff (1943) are modeled in relation to the dbh of the mean basal area tree (= dg). Individual heights are derived from these dg-specific curves and complemented by a random variable. Crown width and height of crown base are calculated by BWINPro sub-models for mature trees as adapted to Saxon data (Schröder 2004). The juvenile growth model contains routines for menu-controlled tree number reduction as well as for imitating the increment-based mortality in case of exceedingly dense stands, following Reineke’s (1933) stand density index concept.

Competition effects on basal area increment

Individual tree development in the “adult” stages in BWINPro is driven by basal area increment (iBA). Crown surface area, age, a competition index (CI), and an indicator for changes in competition control iBA estimations. If tree age is unknown, the program derives species-specific figures from dbh and height. The original model contains the CI C66 and A Diff, an indicator of the length of the simulation period (Nagel 1999). The C66 index identifies competitors of a tree either as all trees belonging to the same stand (distance-independent mode) or by checking a fixed critical radius (distance-dependent mode). Forest conversion, however, results in a large variety of spatial structures that require a more flexible competition index in order to adequately consider the individual situation (Hanewinkel and Pretzsch 2000). To find a CI model applicable to these stands, the C66 index was tested against a number of other CIs for their contribution to accuracy and precision of the basal area estimation. Competing neighbors were identified in a distance-dependent mode by circular zones of influence with different radii and by vertical search cones with opening angles that varied from 40 to 80°. Tests of CIs were carried out using partial correlation and multiple linear regression analysis, focusing on competition-increment relationships in pure and mixed stands of adult spruce, pine, and beech. The resulting regression models were analyzed for their coefficient of determination, their standard error, and the corresponding distribution of residuals. Assessment of these values was directed at finding a biologically realistic model with reliable estimates for all three relevant species.

Modeling mortality

The original BWINPro program (Version 6.0) uses species-dependent maximum values of C66 (C66 max) based on Reineke’s (1933) stand density index model to limit the survival of trees and the resulting stand density (Nagel et al. 2002). The C66 max model, however, does not sufficiently account for the individual growing situation in stands under conversion, particularly when calculated in the distance-independent mode (see Competition effects on basal area increment). Therefore, additional research was necessary to integrate tree dimension and increment into mortality estimation. Preliminary studies with Saxon data confirmed that a three-stage model with a logistic regression function as the central element and mortality likelihood functions provides the best fit to the available data (Hamilton 1986; Hasenauer 1994; Dursky 1997; Monserud and Sterba 1999). Parameterization results for the logistic function were assessed using the Chi-square independence statistic and Wilcoxon’s test for identical results of sub-models derived from random samples of the original data. For the Chi-square statistic, ten sub-series of the original data were set up by repeated random division of all data into proportions of 90% for parameterization and 10% for validation. Wilcoxon’s test was applied to estimate model stability by analyzing differences in precision between the ten-parameterization series. Large differences in variance between the respective 90% sub-samples and the 10% sub-samples required the application of this non-parametric test.

Results

Juvenile growth model for beech and oak

In the new module for simulating growth in advance-planted layers, young trees are established in a regular pattern (i.e., as dots in lines). The user can define the details of spatial distribution and their degree of randomness within wide margins. As a consequence of Chi-square tests for types of distribution in trial plot data, initial dbh and height for single trees are derived from Gaussian distributions. Future dbh and height distributions result from the subsequent individual growth processes.

Analyses of the hemispherical photos show that light availability in the second layer depends on the species forming the canopy. Given the same canopy crown area per m2 ground surface (CA/m2), diffsf under pine is approximately 0.1 (i.e., 10%) higher than under spruce. In a pine-beech mixed stand in Northwest Saxony with 0.49 CA/m2, for example, average diffsf is 0.25 at a site density index for pine = 0.68. In a beech-spruce stand in the Ore Mountains, average diffsf is 0.16 at a site density index = 0.52 and 0.47 CA/m2 for spruce. As a result, two separate parameter sets depending on the dominant canopy species were established for modeling juvenile growth in beech (see Table 3). The analyzed light variables considerably influence growth only for oak under pine and for beech under spruce. In the oak chronosequence, dbh is significantly larger on plots with significantly higher diffsf values. For beech under spruce, height increment correlates significantly with tree-specific diffsf, Z10, and PAR values (partial correlation coefficient R part = 0.27, 0.21, and 0.19, respectively, at P < 0.01; n = 242).

Juvenile growth follows different patterns on the analyzed beech and oak chronosequence plots: In beech, the most susceptible variable to competition influences is the mean annual increment (MAI) in height. Juvenile oak, however, does not show any stable partial correlation of MAI in height with competition indices (CIs) over more than one plot. Instead, there are highly significant partial correlations (P < 0.01) to CIs for MAI in dbh and basal area on all plots. Partial correlation coefficients (R part) for Hegyi’s (1974) CI versus MAI in dbh range from −0.66 to −0.76. For beech, MAI in height is modeled using the CI proposed by Schröder (2004). Maximum partial correlation per plot ranges from R part = −0.61 to −0.7.

Competition effects on beech height increment are best captured by two separate CIs for horizontal (CI h ) and vertical (CI v ) competition. In oak, a general CI (CI g ) including all selected competitors performs better than separate CIs. The maximum coefficient of determination (R 2adj = 0.84) is produced by a model using basal area (BA) increment as dependent variable. Nevertheless, an alternative approach focusing on dbh increment (R 2adj = 0.69) was chosen because the corresponding residuals are only homoscedastic for this option while showing significant trends for BA-based estimations. Additionally, BA values derived from predicted dbh are closer to observed BA values than those estimated directly by means of a BA increment model. On this basis, the following equations were determined:

where ih = annual height increment (in cm), a 0–a 4 = parameters, h = initial height, t = initial age, id = annual dbh increment (in mm), d = initial dbh. The normally distributed random figure ε can be used to simulate contingent effects such as parasites or favorable micro-site. In subsequent predictions ε is defined to be not serially correlated. Equation (2) is applied in the beech sub-model with different parameter values for pine and spruce as canopy species, respectively, Eq. (3) is used in the oak sub-model where pine is the only overstory species that could be analyzed. Linear regression led to a standard error (SE) = 9.8 cm with R 2 = 0.63 for Eq. (2) and to SE = 0.39 mm with R 2 = 0.69 for Eq. (3). Values for parameters a 0–a 4 are given in Table 3.

Competition effects on basal area increment

The alternative model for individual basal area increment of pine, spruce, and beech under Saxon growing conditions is based on the original function in BWINPro:

where iBA = basal area increment in cm2 per 5 years, CSA = crown surface area in m2, t = age, CI c = difference in CI before and after thinning and mortality, A Diff = length of the simulation period, a 0–a 5 = parameters; ε is a random figure allowing for “chance” variation (see Eq. (2); Nagel 1999). OLS-regression of Eq. (4) against Saxon data produced a maximum R 2 and minimum standard error by including a crown-size type CI as described by Biging and Dobbertin (1995):

where CA = horizontal crown area, CDF = species-related crown density factor, i = subject tree, j = competitor(s), n = number of competitors. As a result of the fisheye-photo analyses (see Juvenile growth model for beech and oak), CDF was set at 0.8 for spruce, 0.4 for pine, and 1.0 for beech. CA is the crown area at height of greatest crown width (= height −0.66·crown length) as long as this height is within the search cone. If the search cone cuts a competitor’s axis above this point, CA is calculated with the crown diameter at intersection height. The variable A Diff did not show any significance for Saxon data and was therefore excluded from the equation in the regional version. Table 2 compares the results of multiple regression analyses of Eq. (4) with CI_CA and C66, respectively.

Because of its significant contribution to the model for all three species, CI_CA was chosen to replace C66 for distance-dependent basal area estimation in the Saxon version of BWINPro. T-tests of the mean values of predicted and observed increments did not reveal significant differences in any of the three species. Distance-independent prognoses may still be run using a C66 model that was parameterized for Saxon data because no other distance-independent CI significantly exceeded the level of accuracy of the original index. Parameters for the respective equations are given in Table 3. As an example of the positive effects of introducing an alternative CI, Fig. 2 shows the values of annual basal area increment (iBA) as predicted by (1) the original BWINPro distance-independent sub-model, (2) the regionalized version of the iBA model including C66, and (3) the regionalized version of the iBA model including CI_CA. Measured values are plotted over estimations. The standard error of the estimate decreases from (1) to (3). All models show a slight trend to underestimate measurements with increasing values. This trend will be discussed in Sect. Competition effects on basal area increment.

Values of annual basal area increment iBA in Norway spruce (n = 1,590) as estimated with the original BWINPro version (a) and with the regionalized version for Saxony (b, c). Values were predicted in b using the C66 competition index which was replaced in c by the new CI_CA index. Models for b and c were parameterized for the Saxon data pool before testing CI effects. SE = standard error of the estimate

Modeling mortality

The alternative sub-model introduced into the Saxon BWINPro version estimates the individual mortality of a tree in a three-step algorithm. It was calibrated for spruce, pine, and beech (Röhle et al. 2004). A logistic function computing a vitality-indicating F-value (0 for death, 1 for survival) is the first part of the model:

where d = dbh, h/d = height-to-dbh ratio, ig = basal area increment of a tree during the previous 5-year period. Parameters a 0–a 3 were obtained by applying the maximum likelihood method to weighted samples with equal numbers of dead and live trees from a wide array of frequently measured plots in Saxony and adjacent regions. In the second step, species-dependent inverse-exponential functions assign a specific value of mortality likelihood (ML) to the individual F-value of a tree:

These functions transform the values of 0 < F < 1 including the artificial threshold of 0.5 between dead and live trees into likelihood values reproducing mortality as observed in the field for given intervals of F. Parameters a 0–a 2 were derived from non-linear regression against a data set consisting of mean mortality rates in eight classes of adequate numbers of trees with decreasing F (class 1: 1 > F ≥ 0.95, class 2: 0.95 > F ≥ 9 etc.). Equation (7) is also necessary to avoid classification problems arising from the non-linear distribution of the residuals of Eq. (6). The final step of the model compares ML (%) to an equally distributed random number MZ (0 ≤ MZ ≤ 100) in order to simulate the dichotomous decision about survival or death. If ML > MZ, the tree in question is classified as “dead” (Dursky 1997). Except for 2 out of 20 sub-series (10 for live trees and 10 for dead ones) in beech, Chi-square independence tests revealed no significant differences in the classification of dead and live trees, respectively. Wilcoxon’s test for identical precision in the ten partial models per species did not reveal any significant differences, so the model can be assumed as being stable for all three species (for both tests, statistical significance was P < 0.05). The results of function (7) needed minor adjustment: Parameterization led to ML-values that were significantly too large for the range 0.8 < F < 1. The effect of too many vital trees classified as “dying” was remedied by inserting a linear function responsible for the mentioned range of F rather than using the original inverse-exponential function. As indicated above, the new mortality model is only applied to mature trees higher than 15 m. Juvenile mortality in the Saxon BWINPro version is estimated on stand-density level (see Juvenile growth model for beech and oak). For all species other than spruce, pine, and beech, the original C66 max model is still being used for lack of regional data.

Parameters

Table 3 compiles the parameters estimated by regression analyses for the equations described above. Parameterizations were carried out for spruce, pine, and beech; in oak, only the juvenile growth model and the adult height growth model were adapted to Saxon data.

Discussion

For the purposes of the following section, the original version of BWINPro developed for Lower Saxony is labeled BWINPro-L and the new Saxon version BWINPro-S. A number of examples shall be given of the tests conducted to compare BWINPro-S to the original model and to conventional yield tables. To examine the three separate sub-models described above, indicators like bias, precision, and accuracy were computed (Pretzsch 2001; Schröder 2004). We also tested BWINPro-S as a whole package in order to evaluate the combined effects of the different levels of adaption and extension (Monserud 2003).

When assessing the test results, it is important to consider that virtually all suitable data were used for the parameterization of BWINPro-S in order to get the best possible results from the available information. In some cases, additional data were available for thorough evaluations of the equations and parameters under variable conditions (as outlined by Soares et al. 1995). Most tests, however, consisted of analyses of bias and precision, patterns in residuals, and assessments of model behavior compared to trial plot data and alternative simulation tools such as yield tables. Therefore, the following sections do neither represent “validations” nor “verifications” in the strict sense, because no real test of the model’s logical correctness was carried out (besides, a statistical model cannot be verified, i.e., be proved for the truth of its output; Monserud 2003). They should rather be seen as contributions to “model criticism” and to the evaluation of inferences made from the model, because “useful insights can also be obtained with the data used to fit the model” (Vanclay 1999). New and independent data will become available in the near future as an effect of the application of BWINPro-S within the Saxon forest authority. This should be used as an opportunity for further tests and evaluations against fully independent data and will most certainly lead to re-calibration of various parts of the model. Until then, the following examples shall help to clarify the region and the conceptual frame within which BWINPro-S behaves satisfactorily. They shall also indicate the areas where further research is necessary.

Juvenile-growth model for beech and oak

In contrast to similar investigations by Golser and Hasenauer (1997), the juvenile growth model does not involve potential increments. It directly estimates individual increment because measured increment values from the Saxon plots frequently exceed any limiting function. No reference data were available to create potential asymptotic curves as proposed by Golser (1997). Limiting functions are only applied to the resulting height or dbh values, thus accounting for inter-annual increment variation and providing realistic limits for growth.

The effects of the individual growing situation may be seen on single-tree level and on stand level. To illustrate the impact of stand-level competition, Fig. 3 shows the development of mean height in the beech understory as modeled by BWINPro-S for different stand densities (SDI) of the spruce overstory.

Mean height development in juvenile beech under spruce overstory of varying stand density. SDI (= stand density index) figures relate to the yield table by Wenk et al. (1985) for Norway spruce in East Germany

For beech under pine, the effect of canopy competition can be summarized in similar curves. It is generally less obvious, however, due to differences in crown density and tree numbers per hectare between the pine-beech and the spruce-beech chronosequences. The cumulative effects of individual dbh development in the juvenile layer as modeled by stand diameter curves and chance variation is shown in Fig. 4. Dbh distributions after four simulation cycles for a mixed pine-beech stand are given as averages resulting from 10 model runs.

The application of different CIs for modeling early growth in beech and oak reflects distinctions in the available data (for oak, planted trees as well as trees sown by European jay Garrulus glandarius L. were measured). It can also be seen as a result of the specific growth patterns of the respective tree species (Otto 1994).

As noted by Zhao et al. (2004), tree size might be a variable more useful and more often available than tree age for growth models in mixed stands. Juvenile growth in oak is already being modeled based on dimension (dbh). For the beech sub-model, information on age is still needed because of its significant influence on the goodness of fit. Considering the increasing importance of natural regeneration in forest conversion policy (Zimmermann 2000), age data will become scarcer and should be replaced also in the beech sub-model by appropriate variables in the future.

Competition effects on basal area increment

The sub-model for the development of adult trees shall be evaluated by an exemplary analysis of four experimental stands in Saxony (see Table 4). Predictions derived from yield tables applied in Saxony, estimations with BWINPro-L and estimations with BWINPro-S are compared to data recorded over several time periods in these stands. For all simulated data, their relative estimation error was computed as (estimated value − real value)/real value with “real” representing the measured figure (Bortz 1999).

The stands Waldschänke and Massenei were used for evaluating model performance for pine, Markersbach for beech, and Tannenhaus for spruce. Growth data from two of these stands (Markersbach and Tannenhaus) were part of the data set used for model calibration; the other two had been excluded because of data gaps. In spite of their limited value for “validation” (see above), the comparisons are presented here because no other independent experimental stands were available as representatives for the average conditions in Saxony.

Because tree coordinates were known on all plots, basal area increment was estimated in the distance-dependent mode. The resulting relative estimation errors of the three models for the main growth variables dg and hg (dbh and height of mean-basal area tree) are given in Fig. 5.

Relative errors for estimation of height and dbh development with yield tables (YT) and two versions of BWINPro. Errors in % of the measured value are standardized for a prediction period of 5 years. Acronyms indicate the experimental stands Waldschänke (WS Pinus sylvestris), Massenei (MN P.s.), Markersbach (MB Fagus sylvatica) and Tannenhaus (TH Picea abies)

BWINPro-L and BWINPro-S show a significantly higher flexibility in predicting growth than the respective yield tables (Fig. 5). One important reason for this is that yield tables are confined to a certain thinning and harvesting regime which, in practice, can hardly be followed over a longer period of time due to varying natural conditions and silvicultural strategies (Wenk et al. 1990; Röhle 1995). Local peculiarities may be simulated much better with models that are capable of accounting for the particular history and growing conditions (such as height-to-age ratio) of the stands (Pretzsch et al. 2002). On average, BWINPro-S performed better than BWINPro-L because of the adaption to regional data and introduction of new elements. For spruce, BWINPro-S shows a bias in basal area increment (iBA) estimation that is 20% of the value that results from applying BWINPro-L to Saxon data (10.6 vs. −2.2 cm2/year). Accuracy of prediction improved from 19.4 to 10.4 cm2/year. The positive trend in modeling spruce iBA (Fig. 2) is an expression of the data available for parameterization from the few stands with mean dbh > 45 cm. Measurements come from a period with accelerated growth due to favorable weather conditions and heavy thinnings in favor of large trees in the late 1990s (Spiecker 2000). The underestimation of large iBA values was accepted in this case because it proved to reduce overestimation of increments measured in older stands in other periods. The distance-dependent increment model did not benefit from these older data, because they often had been collected on a distance-independent level (Röhle 1995). For beech, bias fell from −3.5 (BWINPro-L) to −1.8 cm2/year (BWINPro-S) while accuracy was enhanced from 10.6 to 8.4 cm2/year. For pine, however, no significant improvements were achieved by introducing the alternative competition index. BWINPro-L and the regionalized equation using C66 performed at equal levels of accuracy and bias while the Saxon distance-dependent sub-model showed a poorer representation of the original data (see Table 2; Schröder 2004). Limited data and species-dependent competition behavior (Otto 1994) are very likely to contribute to this phenomenon.

Height growth models were improved for all three species by integrating locally derived top-height curves over age as contained in the corresponding yield tables (Wenk et al. 1990; Schröder 2004). These adaptions were of particular importance because BWINPro’s growth model relies on self-calibrating procedures based on the actual height-to-age relation (see The simulator BWINPro 6.0: model description). By including both age and a measure of size in some crucial model functions [see Eqs. (2), (4)], the simulator predicts current increment from accumulated past increments and is thus limited in its possible answers to factors that severely modify growing conditions (Hasenauer 2000). Future model improvements should focus on the substitution of age by other variables, especially in the context of forest conversion to uneven-aged mixed stands where information on individual age is an exception rather than a rule. Routines that estimate a virtual age (as used in BWINPro) are a first step towards this goal.

Modeling mortality

The mortality sub-models in BWINPro-L and BWINPro-S differ in their mathematical algorithms and in the resulting estimations. Because of its strict connection to C66 values, which are in turn a function of tree height, BWINPro-L tends to focus mortality only on smaller trees. “Chance” mortality (Vanclay 1999) cannot be simulated. In accordance with trial plot data, the new three-staged approach in BWINPro-S generates mortality also in dominant trees. By including individual increment data, the mortality sub-model is connected to the specific competition situation. To evaluate the relations between individual-tree increment and the resulting F-value, exemplary trees with a dbh of 20 cm and a height of 20 m were created for spruce, pine, and beech. Corresponding F-values were then calculated in dependence on the annual dbh increment in the previous five-year period (see Fig. 6).

According to the logistic model, F-values > 0.5 indicate a relatively high chance for survival while F-values < 0.5 represent trees likely to be classified as “dead” (Dursky 1997; Vanclay 1999). The new model requires significantly higher increment values for pine than for spruce or beech to cross the 0.5-line (Fig. 6). This model behavior confirms analyses of trial plot data from Saxony, which proved the logistic function to slightly overestimate mortality in pine, particularly for higher age and dbh classes. One reason for this is the narrow database for parameterization of the pine sub-model coming from stands between 46 and 69 years old. Predictions for older stands have therefore to be judged with appropriate caution. Model updates with data from older plots are required to allow reliable prognoses for a wider range of pine stands. Currently, the C66 max-model should still be applied for conditions that are outside the data available for parameterization. For spruce and beech, mortality rates derived from the new model follow observed data with no obvious extrapolation errors.

Summary and outlook

Adaption and purpose-oriented extension of the growth model BWINPro have led to significant improvements in model performance under typical Saxon conditions. Analyses and prognoses in structurally diverse mixed stands created by active conversion measures have become possible by integrating additional sub-models. Central elements of BWINPro’s growth model were parameterized and partly altered in order to fit regional data for Norway spruce, Scots pine, and European beech. As a prerequisite, the representation of major influences on stands and trees such as early growth, competition, and mortality in the underlying mathematical models was analyzed and, if necessary, enhanced. The sub-model for estimating basal area increment was supplemented by an additional distance-dependent competition index. Development of juvenile trees in advance-planted layers under canopy is estimated by a separate sub-model integrating competition influences by overstory trees as well as by neighboring young trees. The derived regression models allow stable predictions of individual dbh, height, and crown size over a period of 20 years for young oak under pine canopy and for young beech under spruce or pine canopy, respectively. In addition to the new basal area increment model for adult trees, an alternative sub-model for individual-tree mortality was parameterized using logistic regression and non-linear regression analysis. Limited data for pine stands led to parameters likely to produce unstable predictions when extrapolating the model. For spruce and beech, however, mortality can now be satisfactorily simulated in relation to dimension and increment of a tree, which indirectly incorporates its specific competition situation into model predictions. Trials with BWINPro and its regionalized version BWINPro-S in comparison to yield table predictions proved the single-tree oriented computer models to be more flexible in accounting for variable species mixture, age composition, and spatial structure. The reliability of estimations, however, is closely connected to the underlying data. If applications take into account the background and database of the presented study, the resulting simulator is well suited for forest growth and yield estimations not only in structurally diverse mixed pine-beech stands, but also in single-layer pure spruce stands. Regional relevance ranges from the pleistocenic lowland conditions in Northeast Germany to sites on Paleozoic rocks in chilly and humid highland climate, which prevail in the Ore Mountains (Fürst et al. 2004).

Current research on BWINPro focuses on the estimation of quality-related tree properties (Schmidt 2001) and on the application of the simulator within larger systems to support decisions in long-term forest planning (Döbbeler and Spellmann 2001; Sodtke et al. 2004). Distribution and further development of the program and its components were enhanced by introducing a Java platform as a server for the various regional working groups. The adaptions, modifications and newly developed components described above have been included in a regional program package labeled BWINPro-S. This package is currently introduced into forest planning and management by the Saxon State Forest Administration (SFA). Co-operation projects between Dresden University and the SFA have produced additional modules facilitating the detailed simulation of thinning and harvesting on a single-tree basis and economic evaluations of silvicultural options. In accordance to the distribution policy for BWINPro, a complete shareware version of BWINPro-S in German is available on the internet (http://www.forst.tu-dresden.de/Waldwachstum/simulator_ww.htm). The original program parameterized for Lower Saxony and adjacent regions can be downloaded via http://www.nw-fva.de/index.php?id = 194. On this site there is also a Java version of the simulator (BWINPro 7) containing a number of important additions and updates of model elements.

Notes

Throughout the text, tree species will be denominated by “beech” for Fagus sylvatica, “oak” for Quercus ssp., “pine” for Pinus sylvestris, and “spruce” for Picea abies.

References

Biging GS, Dobbertin M (1995) Evaluation of competition indices in individual tree growth models. Forest Sci 41:360–377

Börner M, Eisenhauer D-R (2003) Zur Holzqualität unterständiger Häher-Eichen in sächsischen Kiefernbeständen. Forst Holz 58:128–131

Bortz J (1999) Statistik für Sozialwissenschaftler. 5th rev edn. Springer, Heidelberg

Döbbeler H, Spellmann H (2001) Methodological approach to simulate and evaluate silvicultural strategies under climate change. Forstwissenschaftliches Centralblatt 121(Supplemantry1):52–69

Dursky J (1997) Modellierung der Absterbeprozesse in Rein- und Mischbeständen aus Fichte und Buche. Allgemeine Forst Jagdzeitung 168:131–134

Fürst C, Bitter AW, Eisenhauer DR (2004) Sustainable methods and ecological processes of a conversion of pure Norway spruce and Scots pine stands into ecologically adapted mixed stands. Eugen Ulmer, Stuttgart

Golser M (1997) Modellierung der Naturverjüngungsentwicklung in Mischbeständen. PhD thesis, Wien

Golser M, Hasenauer H (1997) Predicting juvenile tree height growth in uneven-aged mixed species stands in Austria. For Ecol Manag 97:133–146

Hamilton DA (1986) A logistic model of mortality in thinned and unthinned mixed conifer stands of northern Idaho. Forest Sci 32(4):989–1000

Hanewinkel M, Pretzsch H (2000) Modelling the conversion from even-aged to uneven-aged stands of Norway spruce (Picea abies L. Karst.) with a distance-dependent growth simulator. For Ecol Manag 134:55–70

Hasenauer H (1994) Ein Einzelbaumwachstumssimulator für ungleichaltrige Fichten-Kiefern- und Buchen-Fichtenmischbestände. Forstl. Schriftenreihe, Univ. f. Bodenkultur, Wien

Hasenauer H (2000) Die simultanen Eigenschaften von Waldwachstumsmodellen. Parey, Berlin

Hasenauer H (2006) Sustainable forest management. Springer, Heidelberg

Hegyi F (1974) A simulation model for managing jack-pine stands. In: Fries J (eds) Growth models for tree and stand simulation. Royal College of Forestry Research Notes, Stockholm, pp 74–90

Klimo E, Hager H, Kulhavy J (eds) (2000): Spruce monocultures in Central Europe - Problems and Prospects. EFI Proceedings No. 33, Joensuu

Landsberg J (2003) Modelling forest ecosystems: state of the art, challenges, and future directions. Can J For Res 33:385–397

Michailoff I (1943) Zahlenmäßiges Verfahren für die Ausführung der Bestandeshöhenkurven. Forstwissenschaftliches Centralblatt 65(6):273–279

Monserud RA (2003) Evaluating forest models in a sustainable forest management context. FBMIS 1:35–47 (http://www.fbmis.info/A/3_1_MonserudR_1)

Monserud RA, Sterba H (1999) Modeling individual tree mortality for Austrian forest species. For Ecol Manag 113:109–123

Nagel J (1999) Konzeptionelle Überlegungen zum schrittweisen Aufbau eines waldwachstumskundlichen Simulationssystems für Nordwestdeutschland. Sauerländer’s, Frankfurt am Main

Nagel J, Albert M, Schmidt M (2002) Das waldbauliche Prognose- und Entscheidungsmodell BWINPro 6.1. Neuparametrisierung und Modellerweiterungen. Forst Holz 57:486–493

Nagel J, Schmidt M (2006) The silvicultural decision support system BWINPro. In: Hasenauer pp 59–63

Otto H-J (1994) Waldökologie. Eugen Ulmer, Stuttgart

Peng C (2000) Growth and yield models for uneven-aged stands: past, present and future. For Ecol Manag 132:259–279

Pommerening A, Murphy ST (2004) A review of the history, definitions and methods of continuous cover forestry with special attention to afforestation and restocking. Forestry 77:27–44

Porté A, Bartelink HH (2002) Modelling mixed forest growth: a review of models for forest management. Ecol Modelling 150:141–188

Pretzsch H (2001) Modellierung des Waldwachstums. Parey, Berlin

Pretzsch H et al (2002) Recommendations for standardized documentation and further development of forest growth simulators. Forstwissenschaftliches Centralblatt 121:138–151

Reineke LH (1933) Perfecting a stand density index for even-aged stands. J Agric Res 46:627–638

Röhle H (1995) Zum Wachstum der Fichte auf Hochleistungsstandorten in Südbayern. Mitteilungen aus der Staatsforstverwaltung Bayerns No. 48

Röhle H (1999) Datenbankgestützte Modellierung von Bestandeshöhenkurven. Centralblatt gesamte Forstwesen 116:35–46

Röhle H (2001) Wuchsverhalten und Konkurrenzdynamik von Waldbeständen in der Umbauphase. Beiträge für Forstwirtschaft und Landschaftsökologie 35:182–187

Röhle H, Münder K, Schröder J (2004) Modeling of individual-tree growth with special respect to competition effects. In: Fürst et al pp 198–208

Schmidt M (2001) Prognosemodelle für ausgewählte Holzqualitätsmerkmale wichtiger Baumarten. PhD thesis, Göttingen

Schröder J (2004) Zur Modellierung von Wachstum und Konkurrenz in Kiefern/Buchen-Waldumbaubeständen Nordwestsachsens. Eugen Ulmer, Stuttgart

Soares P, Tomé M, Skovsgaard JP (1995) Evaluating a growth model for forest management using continuous forest inventory data. For Ecol Manag 71:251–265

Sodtke R, Schmidt M, Fabrika M, Nagel J, Dursky J, Pretzsch H (2004) Anwendung und Einsatz von Einzelbaummodellen als Komponenten von Entscheidungsunterstützenden Systemen für die strategische Forstbetriebsplanung. Use and application of individual tree growth models as components of decision support systems for long-term forest enterprise planning. Forstarchiv 75:51–64

Spiecker H (2000) Growth of Norway spruce (Picea abies [L.] Karst.) under changing environmental conditions in Europe. In: Klimo et al (eds) pp 11–26

Spiecker H, Hansen J, Klimo E (eds) (2004) Norway spruce conversion. Options and consequences. Brill Academy, Leiden Boston Köln (= EFI Research Reports No. 18)

Thomasius H (1992) Prinzipien eines ökologisch orientierten Waldbaus. Forstwissenschaftliches Centralblatt 111:141–155

Vanclay JK (1999) Modelling forest growth and yield. Applications to mixed tropical forests. Reprinted ed. CABI Publishing, Wallingford

Vanclay JK (2003) Realizing opportunities in forest growth modelling. Can J For Res 33:536–541

Wagner S (1994) Strahlungsschätzung in Wäldern durch hemisphärische Fotos. Methode und Anwendung. PhD thesis, Göttingen

Wenk G, Römisch K, Gerold D (1985) DDR-Fichtenertragstafel. Tharandt

Wenk G, Antanaitis V, Smelko S (1990) Waldertragslehre. Deutscher Landwirtschaftsverlag, Berlin

Wensel LC, Meerschaerdt W, Biging GS (1987) Tree height and diameter growth models for Northern California conifers. Hilgardia 55(8):1–20

Wykoff WR, Crookston N, Stage A (1982) User’s guide to the stand prognosis model. General Technical Report INT-133, Ogden

Zhao D, Borders B, Wilson M (2004) Individual-tree diameter growth and mortality models for bottomland mixed-species hardwood stands in the lower Mississippi alluvial valley. For Ecol Manag 199:307–322

Zimmermann R (2000) Ziele und Ergebnisse des Waldumbaues im Sächsischen Forstamt Falkenberg. Forst Holz 55:415–418

Acknowledgments

Research was funded by the German Federal Ministry of Research and Education (joint project “Future-Oriented Forestry”) and by the State Forest Administration of Saxony. The authors gratefully appreciate the full access to the source code of BWINPro they were given by Prof. J. Nagel and the support they received from his team at the Forest Research Station of Lower Saxony in Göttingen. We also wish to thank Mrs. A. Michel for improving the English and two anonymous reviewers for their contributions to this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by Hans Pretzsch.

An erratum to this article is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10342-007-0178-2.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schröder, J., Röhle, H., Gerold, D. et al. Modeling individual-tree growth in stands under forest conversion in East Germany. Eur J Forest Res 126, 459–472 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10342-006-0167-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10342-006-0167-x