Abstract

This study was conducted using focal animal sampling on the west ridge group of the Sichuan snub-nosed monkey (Rhinopithecus roxellana) located in the Zhouzhi National Nature Reserve on the north slope of the Qinling Mountains, from 8 July 2003 to 24 May 2004. The difference in the average frequency of copulations for each focal male for each month was significant (F = 3.068, P = 0.016, one-way ANOVA test) with the majority of copulations occurring between September and November. Duration of intromission ranged from 2 to 39 s, with a mean of 16.0 ± 0.4 s. Females initiated 627 courtship attempts (96.2%), while males only initiated 3.8%. Both adult females (72.8%) and sub-adult females (27.2%) were involved in sexual interference acts. Females who gave birth in 2004 performed more sexual interference acts than would be expected by chance in the reproductive period of 2003 (X 2 = 13.73 > X 2 0.005,2, df = 2, P < 0.005). Male response to female interference was equally divided into “solicitor mounting” and “interrupter mounting”. The resident males of one-male units were not observed to mount both the solicitor and the interrupter or mount neither following female solicitation interruptions. Three post-conception copulations were also observed in this study. These results suggest a skewed sexual competition, with multiple females competing for a single male, which was shown by courtship attempts and female interference.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Darwin’s “sexual selection” theory arises through a direct struggle between members of the same sex and the mating preferences of one sex for the other (Paul 2002). In primate research, although male–male competition for mates and female mate choice are the common causes of sexual selection, female–female competition over males is especially important in polygynous species (Smuts 1987). The Sichuan snub-nosed monkey (Rhinopithecus roxellana) is a seasonal breeding species of colobine endemic to China, and lives in a multi-leveled social system (Chen et al. 1983; Zhang et al. 2003). The basic social and reproductive unit is the harem or one-male unit (OMU), consisting of a single resident male, a number of adult females, sub-adult females, juveniles and infants (Zhang et al. 2003). It has been suggested that sexual competition in this polygynous species may have a skewed representation; females faced with multiple competitors will exhibit a high level of sexual competition, while the single resident male will not experience within-group sexual competition (Smuts 1987).

Long-term tracking in the wild found that the Sichuan snub-nosed monkeys were not well habituated to researchers and could not be observed continuously for long periods of time due to the high elevation and cliff habitat. All sexual behavior information on this primate, such as seasonality of mating and births, reproductive behavior, and menstrual cycle and pregnancy (Qi 1989; Clarke 1991; Ren et al. 1995, 2002, 2003; Yang 1998a, b; Zhang et al. 2000; Yan et al. 2003a, b) is based to date on captive observation. Since 2001, by provisioning, we have started to observe sexual behavior in detail in wild conditions, and have so far reported extra-unit sexual behavior and female multiple copulations (Zhao et al. 2005; Li and Zhao 2005). In this study, we firstly address copulation behavior of wild Rhinopithecus roxellana, predominantly female courtship and sexual interference. Our goal is to compare those with captive research results and testify whether skewed sexual competition really occurs in this wild species. This study will also conduce to reproductive breeding in the captive.

Methods

Study site and species

The study site is located in Zhouzhi National Nature Reserve on the north slope of the Qinling Mountains. The approximate altitude was 1,600 m and the composition of the forest varies with altitude from deciduous broadleaf forests at the lowest elevations to mixed deciduous broadleaf/coniferous forests above 2,200 m, grading to coniferous forests above 2,600 m (Li et al. 2000).

The reserve is host to many rare species endemic to China, including the only resident primate species, the Sichuan snub-nosed monkey (R. roxellana). Two polygynous groups of this species were present in the study site, the east ridge group (ERG) and the west ridge group (WRG). The WRG, which consisted of one-male units, was the focus for this study (Li et al. 2000; Zhang et al. 2003).

Food provisioning

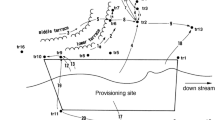

Provisioning of the study group was started on 24 October 2001. A 15 × 30 m provisioning site was set up at Sanchakou (1,646 m above sea level) in the Gongnigou valley (33°48′68″N, 108°16′18″E). In the early morning, our assistants searched for monkeys. The monkeys were herded towards the provisioning site at approximately 0900 hours every day when research was being conducted. Apples, radishes, and corns were provided three times per day (1000, 1200, and 1400 hours), approximately 200 g per monkey per day in total. Compared with daily total diet of R. roxellana (Qi 1989), the provisioned food is very limited and the influence of the artificial factors would be minimal on the whole. After provisioning, the monkeys quickly left the provisioning site for adjacent trees and freely moved within the area. The monkeys' nightly roosts were located within a radius of approximately 3 km of the provisioning site. At the end of the observation period, the monkeys were free-living in the west ridge. During the study period, we made our observations from distances of between 0.5 and 50 m.

Date collection

Observations were conducted on the west ridge group from 8 July 2003 to 24 May 2004 (116 days total). Thirty-nine individuals, 6 males and 33 females, were identified during this study. Individual monkeys were identified by their prominent physical characteristics, such as body size, pelage color, hair patterns of head and tail end, body disability, and the shapes of granulomatous flanges on both sides of the upper lip (Zhang et al. 2003). Six OMUs were selected from June 2003 to January 2004 and five OMUs from February 2004 to May 2004 based on their membership stability. Individual numbers within the selected OMUs were counted at the start of each observation period (Table 1); no change in the number of adult subjects occurred during this study.

From the subset selected, a single OMU male was selected randomly on each day and followed for as long as possible. We recorded all sexual interactions related to the focal male within its OMU, which especially included focal male-to-female and female-to-focal male courtship gestures, female sexual interference during the focal male’s copulation processes, and post-copulation behavior of the focal males and of their copulation objects. The mean duration of one observation bout is 6.56 h. If visual contact was lost with the focal resident male, a different OMU resident male was selected. Copulation behavior data was collected by focal animal sampling (Altmann 1974). Each target was observed for 58.5–68 h in 2003 and for 12.5–62.5 h in 2004 (Table 1), with the total number of observation hours 374.5 h in 2003 and 281.5 h in 2004. The reproductive period, from September to December, was defined according to Zhang et al. (2000).

Behavioral definitions

Definitions for the behavior recorded in this study period are shown in Table 2.

Data statistics

We used the SPSS 10.0 statistical package to analyze the data. One-way ANOVA and Friedman tests were carried out to determine differences in the average frequency of copulations among focal OMU resident males within each month and season. Correlations were made between female numbers within OMU, female/male courtship frequency and successful rate of female/male courtship, using Pearson Correlation Significance Statistics. Statistical tests were two-tailed.

Results

General description of copulation behavior

Copulation behavior procedure of wild Sichuan snub-nosed monkey generally includes courtship, mounting, intromission and ejaculation (Table 2). Copulations occurred most frequently between September and November with a peak in November. The period between birth peak and copulation peak is approximately 6 months, which is similar to estimates (193–204 days) based on data collected on captive monkeys (Yan et al. 2003a).

A total of 328 copulations were recorded during our observation periods. The difference in the average frequency of copulations for each focal male each month was significant (F = 3.068, P = 0.016, one-way ANOVA test) with the majority of copulations occurring between September and November (Fig. 1).

During the copulation process, the male grasps, with his hind feet, both of the female’s ankles (149 times, 45.4%) or a single female’s ankles (179 times, 54.6%). The double-feet clasp copulation gesture has been described in many Old World monkeys (Dixson 1998), but this is the first reporting for this species. This is in contrast to studies on captive monkeys that have reported only the single-foot clasp (Ren et al. 2002). We observed that it is also common for the male to grasp the female’s hips with his hands during copulation.

The average duration of intromission (16.0 ± 0.4 s) (Table 3) is similar to the average duration reported in previous studies on captive populations, 14.1 ± 0.3 s (Ren et al. 2002). The mean duration of intromission for all focal males was significantly longer in 2003 than in 2004 (df = 5, t = 4.88, P = 0.0028, P < 0.05). This may be because the observation period in 2003 included the peak reproductive period while the observation in 2004 did not.

Post-copulation behavior included males grooming the female (6.1%), females grooming the male (27.1%), huddled together (14.6%), and females moving away from the male (50.0%).

Courtship behavior

Of the total courtship attempts (n = 652), only 25 attempts (3.8%) were initiated by males, and 627 attempts (96.2%) were initiated by females. Prostration was observed in 86.2% of courtship attempts by females, but 13.8% of courtship attempts involved a gesture performed by the female, performing a chest curl, lowering her head and showing her back to the male; no similar gesture has been previously reported in the literature. The important difference between this gesture and prostration is that prostration exposes the female's buttocks while the “chest curl” does not. The most frequent form of observed OMU resident male courtship was “stare courtship”, which occurred in 57.9% of courtship attempts. The second form, “approach courtship”, was observed in 42.1% of courtship attempts.

There was a positive correlation between female numbers and female courtship attempts frequency (frequency/h/female) based on the data recorded on bio-sexual courtship attempts frequency and its successful rate for each OMU while female numbers negatively correlates with female courtship success rate (Table 4).

Female interference

During the focal observations on males, 158 female interference events were recorded. Non-contact sexual interference comprised 28.5% of total interferences. Within this, female interference before copulations made up 15.8% of the sexual interference attempts and vocal display “wuga” during copulations, 12.7%. A total of 71.5% of female interferences were in the form of contact interference. During our study, both adult females (72.8%) and sub-adult females (27.2%) were involved in sexual interference (Table 5). Eight females who gave birth in 2004 performed more interference acts than would be expected by chance (X 2 = 13.73 > X 2 0.005,2, df = 2, P < 0.005) in the reproductive period of 2003.

A total of 46.7% of male responses to female solicitation interruptions were in the form of “solicitor mounting”, while 53.3% were in the form of “interrupter mounting”. We did not observe the OMU resident males mount both the solicitor and interrupter successively or mount neither following a female solicitation interruption.

Post-conception copulations

Most females ceased to copulate once they had conceived (based on the birth records and previously documented conception periods; Yan et al. 2003a). However, some females were observed to be involved in copulation after conception. We observed three post-conception copulations. One female, BT, copulated 3 months before she gave birth. Another female, YL, copulated 1 month before giving birth. There was also an extreme case of post-conception copulation; BX copulated in April 2004, only 4 days before giving birth.

Discussion

Seasonality of birth and copulation

Many colobine species display strict birth seasons, for example, the western black-and-white colobus (Colobus polykomos) (Dasilva 1992) and the capped langur (Trachypithecus pileatus) (Stanford 1990). It is likely that these birth seasons are a common feature of colobines in montane climates, for example, all Himalayan populations of the Hanuman langur (Semnopitheaus entellus) studied had a pronounced December-to-May birth season, presumably because of the seasonality of the mountain climates and food resources (Bishop 1979). Previous studies in captivity have demonstrated that the Sichuan snub-nosed monkey is also a seasonal breeder (Ren et al. 1995). This study reveals that this is also the case in the wild, with the majority of births occurring in spring (March to May), with a peak in April. This is presumably to coincide with the increasing temperature and the ample supply of leaves and buds, which are the preferred food of this species (Chen et al. 1983). It is believed that births must be timed to ensure that there are enough of these food resources available to support the high metabolic demands of lactation and growth of the offspring (Millar 1977). We suggest that the peak of births in wild Sichuan snub-nosed monkeys occur during the time of year with the most favorable environmental condition and food resource availability.

Otherwise, our study revealed that copulation behavior occurred mostly frequently between September and November with a peak in November. The results reported here are similar to the captive report by Zhang et al. (2000). The period between birth peak and copulation peak was approximately 6 months, which is similar to the estimate (193–204 days) based on captive subjects (Yan et al. 2003). The time delay between the copulation season and the birth season was the length of gestation (van Horn and Easton 1979). This result indicated that copulation behavior was concentrated within the time period of most successful conception.

Courtship competition

Polygynous male species experience relatively little sperm competition, and sexual selection is quite different from those that operate in other mating systems (Dixson 1998). The social structure of Sichuan snub-nosed monkeys allows one resident male to monopolize several females. During our study, the males showed a very low number of courtship attempts and a high courtship attempt success rate within their OMUs. This was probably the result of a low level of mate choice experienced by the females (Paul 2002).

In contrast, females compete for sexual access to the breeding male in species living in multi-female, one-male groups (Smuts 1987). Female colobines characteristically solicit the majority of copulations, the western black-and-white colobus being the only recorded exception in harem species (Davies and Oates 1994). For wild R roxellana, females were primary initiators of copulation during our study, which is consistent with the previous study on a captive population (Ren et al. 1995). There was a significant positive correlation between female numbers and female courtship attempt frequency while female courtship attempt frequency was negatively correlated with the rate of female courtship success (Table 4). These results suggest that skewed courtship competition occurs in wild Sichuan snub-nosed monkeys (Lindefors et al. 2004; Quader 2005).

Female interference

Females have been reported to harass copulating pairs in patas monkeys (Erythrocebus patas) (Loy and Loy 1977) and gelada baboons (Theropithecus gelada) (Mori 1979). Sexual interference is also a characteristic of colobines (Davies and Oates 1994), such as gray langurs (Presbytis entellus) (Yoshiba 1968). Sommer (1989) suggested that there might be two advantages for the occurrence of sexual interference by females. Firstly, adult females gain an advantage by imposing abortion on their peers and thus limiting future resource competition for their offspring. Secondly, females may interfere with copulations to prevent ejaculation, thus improving the quality and quantity of sperm available to themselves.

The female sexual interference among wild Sichuan snub-nosed monkeys, which has also been reported in captive animals by Ren et al. (1995), was predominantly exhibited in the reproductive period of 2003 by the eight adult females who gave birth in 2004. This may support the first advantage, as the interfering females continued to interfere outside the 2003 reproductive period and thus had already conceived. The female sexual interference is also a kind of behavioural embodiment of skewed sexual competition for R. roxellana.

Post-conception copulations

We found three cases of post-conception copulations during our study. The purpose of this behavior could be to make paternity confusion so as to protect her new infant (Hrdy 1979), particularly in the case of YL, whose unit was taken over by a new male during the non-reproductive period of 2003 (Wang et al. 2004).

Paternity confusion by the male can only occur if the assumption of a lack of knowledge of the female’s pregnancy is satisfied. An alternative reason, suggested by Sommer et al. (1992) study, is that the post-conception copulation is a female strategy to remove sperm from males, thereby depriving competing females of conception and increasing the availability of resources for their expected infants. Depriving another female of offspring can also result in a strengthening or upgrading of the female's dominance rank, as female intra-unit dominance rises among Sichuan snub-nosed monkeys following giving birth (Li et al. 2006).

References

Altmann J (1974) Observation study of behavior: sampling method. Behavior 49:227–267

Bishop NH (1979) Himalayan langurs: temperate colobines. J Hum Evol 8:251–281

Chen FG, Min ZL, Lou SY, Xie WZ (1983) An observation on the behavior and some ecological habits of the Sichuan snub-nosed monkeys (Rhinopitheus roxellana) in Qinling Mountains. Acta Theriol Sinica 3:141–146

Clarke AS (1991) Social sexual behavior of captive Sichuan snub-nosed monkeys (Rhinopithecus roxellana). Zool Biol 10:369–374

Dasilva GL (1992) The western black and white colobus as a low-energy strategist: activity budgets, energy expenditure and energy intake. J Anim Ecol 61:79–91

Davies AG, Oates JF (1994) Colobines monkeys. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Dixson AF (1998) Primate sexuality. Oxford University Press, Oxford

van Horn RN, Eaton GG (1979) Reproductive physiology and behavior. In: Doyle GA, Martin RD (eds) The study of prosimian behavior. Academic, New York, pp 79–122

Hrdy SB (1979) Infanticide among animals: a review classification, and examination of the implications for the reproductive strategies of females. Ethol Sociobiol 1:13–40

Li BG, Zhao DP (2005) Female multiple copulations among wild Sichuan snub-nosed monkey (Rhinopithecus roxellana) in Qinling Mountains of China. Chin Sci Bull 50:942–944

Li BG, Chen C, Ji WH, Ren BP (2000) Seasonal home range changes of the Sichuan snub-nosed monkey (Rhinopithecus roxellana) in the Qinling mountains of China. Folia Primatol 71:375–386

Li BG, Li HQ, Zhao DP, Zhang YH, Qi XG (2006) Study on dominance hierarchy of Sichuan snub-nosed (Rhinopithecus roxellana) in Qinling Mountains. Acta Theriol Sinica 26:18–25

Lindefors P, FrÖberg L, Nunn CL (2004) Females drive primate social evolution. Proc R Soc Lond B 271(Suppl):101–103

Loy J, Loy K (1977) Sexual harassment among captive patas monkeys (Erythrocebus patas). Primates 18:691–699

Millar JS (1977) Adaptive feature of mammalian reproduction. Evolution 31:370–386

Mori U (1979) Reproductive behaviour. In: Kawai M (ed) Contribution to primatology. Karger, Basel, pp 391–399

Paul A (2002) Sexual selection and mate choice. Int J Primatol 23:877–904

Qi JF (1989) The feed and reproduction of the Sichuan snub-nosed monkeys. In: Chen FG (ed) Progress in the study of Sichuan snub-nosed monkeys. Northwestern University Press, Xi’an, pp 287–292

Quader S (2005) Mate choice and its implications for conservation and management. Anim Behav 89:1220–1229

Ren RM, Yan KH, Su YJ, Qi HJ, Liang B, Bao WY (1995) The reproductive behavior of Sichuan snub-nosed monkeys in captivity (Rhinopithecus roxellana). Primates 36:135–143

Ren BP, Xia SZ, Li QF, Zhang SY, Liang B, Qiu JH (2002) Male copulatory patterns in captive Sichuan snub-nosed monkeys (Rhinopithecus roxellana). Acta Zool Sinica 48:577–584

Ren BP, Zhang SY, Xia SZ, Li QF, Liang B, Lu MQ (2003) Annual reproductive behavior of Rhinopithecus roxellana. Int J Primatol 24:575–589

Smuts BB (1987) Sexual competition and mate choice. In: Smuts BB, Chency DL, Seyfarth RM, Wrangham RW, Struhsaker TT (eds) Primate societies. Part III. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 385–399

Sommer V (1989) Sexual harassment in langurs monkeys (Presbytis entellus) competition for ova, sperm or nurture? Ethology 28:205–217

Sommer V, Srivastava A, Borries C (1992) Cycles, sexuality and conception in free-ranging langurs (Presbytis entellus). Am J Primatol 28:1–27

Stanford CB (1990) The capped langur in Bangladesh: behavioural ecology and reproductive tactics. Contrib Primatol 26:1–179

Wang HP, Tan CL, Gao YF, Li BG (2004) A takeover of resident male in the Sichuan snub-nosed monkey Rhinopithecus roxellanae in Qinling Mountains. Acta Zool Sinica 50:859–862

Yan CE, Jiang ZG, Li CW, Zeng Y, Tan NN, Xia SZ (2003a) Monitoring the menstrual cycle and pregnancy in the Sichuan snub-nosed monkeys (Rhinopithecus roxellana) by measuring urinary estradiol and progesterone. Acta Zool Sinica 49:693–697

Yan CE, Jiang ZG, Li CW, Zeng Y, Tan NN, Xia SZ (2003b) Relationship between sexual solicitations and urinary estradiol in the female Sichuan golden monkeys (Rhinopithecus roxellana). Acta Zool Sinica 49:736–741

Yang XJ (1998a) Observations on the male sexual behaviours of Golden monkey (Rhinopithecus roxellana) in captive. J Gansu Agri Univ 33:345–349

Yang XJ (1998b) Observations on the female sexual behaviours of Golden monkey (Rhinopithecus roxellana) in captive. J Gansu Agri Univ 33:228–233

Yoshiba K (1968) Local and intergroup variability in ecology and social behavior of common Indian langurs. In: Jay PC (ed) Primates: studies in adaptation and variability. Academic, New York, pp 256–398

Zhang SY, Liang B, Wang LX (2000) Seasonality of matings and births in captive Sichuan Sichuan snub-nosed monkeys (Rhinopithecus roxellana). Am J Primatol 51:265–269

Zhang P, Li BG, Wada K, Tan CL, Watanabe K (2003) Social structure of a group of Sichuan snub-nosed monkeys (Rhinopithecus roxellana) in the Qinling Mountains of China. Acta Zool Sinica 49:722–735

Zhao DP, Li BG, Li YH, Wada K (2005) Extra-unit sexual behavior among wild Sichuan snub-nosed monkeys (Rhinopithecus roxellana) in Qinling Mountains of China. Folia Primatol 76:172–176

Acknowledgments

We express our sincere appreciation to Dr. Toshisada Nishida, Dr. Volker Sommer and three anonymous referees for their comments, and to Dr. Daniel White for English revision. We also thank Prof. Alan F. Dixon, Dr. Wada Kazuo and Miss Yisha Ha for their sincere help. The authors are very grateful to the director and staffs of Zhouzhi National Nature Reserve for their support. This study was funded by the grants of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (General Program, No. 30570312, No. 30370202; Key Program, No.30630016), Key Project of Ministry of Education (204186) and Cosmo Oil Eco Card Fund (2005–2009).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

About this article

Cite this article

Li, B., Zhao, D. Copulation behavior within one-male groups of wild Rhinopithecus roxellana in the Qinling Mountains of China. Primates 48, 190–196 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10329-006-0029-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10329-006-0029-7