Abstract

Heavy metal pollution such as water contamination by Pb, Hg, Cu, Cd and Cr ions is induced by rapid urbanization and industrialization and is a major threat to human health. One of the most efficient processes to clean contaminated water is adsorption. Adsorbents such as clay minerals and modified clays are efficient for the removal of metal ions from wastewater. This manuscript reviews current research in heavy metal adsorption by clay minerals such as halloysite, bentonite, montmorillonite, vermiculite and attapulgite, from 2013 to 2017, and highlights the main adsorption mechanisms. The structure, composition and synthesis of various clay minerals and modified clays are presented.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

As the world population increases rapidly, the demand for water will gradually increase, and the need for improved water quality is urgent. Half of the earth’s population will face a water crisis by the year 2025 (Rijsberman 2006). Many researchers have focused on the removal of different toxic pollutants from wastewater in the last several decades (Erdem et al. 2004; Ngah et al. 2008; Fu and Wang 2011; Wang and Xu 2012). Water pollution problems are caused by the use of fertilizers (Choudhury and Kennedy 2005), insecticides (Matur and Davou 2007), herbicides (Parise et al. 2004), soaps and detergents (Jean et al. 2012), as well as industrial activities, including mining (Dhal et al. 2013), electroplating (Dhal et al. 2013), textiles (Perez et al. 2002) and other chemical industries (Lefebvre and Moletta 2006) (Scheme 1). Consequently, the most efficient solution is removing these toxic chemicals before they are released to the ecosystem.

Due to their abundance and toxicity, heavy metals have become a severe environmental problem. The persistence of heavy metals, such as Cu(II), Hg(II), Pb(II), Cd(II) and Cr(VI), in water environments has led to numerous health problems in humans and animals (Elom et al. 2014; Stankovic et al. 2014) . Heavy metals are the major components of inorganic pollutants, such as pesticides, fertilizers, sludge, and municipal waste, which have contaminated large areas of water and land. Heavy metals are carcinogens and may pose a serious health threat to all living beings. Table 1 shows the effects on humans and diseases caused by heavy metals. However, some heavy metals play irreplaceable roles as essential substances in mammalian metabolic systems, for instance, zinc plays an important role in the development of the brain and intelligence; copper is a constituent element of hemocyanin in human body; manganese can promoting the normal growth and development of bone, and maintain the normal metabolism of glucose and fat (White and Broadley 2009).

Exposure to heavy metals beyond safe levels can cause serious damage. Table 2 shows the maximum allowable limits of various heavy metals (Ahmaruzzaman 2011; Uddin 2017). In order to mitigate the uncontrolled emissions of these harmful heavy metals in wastewater, recent treatment technologies for heavy metals have been proposed worldwide. Several water treatment techniques, such as solvent extraction (Navarro et al. 2007), evaporation (Jakob et al. 1996), chemical precipitation (Matlock et al. 2002), ion exchange (Kapoor and Viraraghavan 1995), electrochemical treatment (Chen 2004), membrane filtration technologies (Mavrov et al. 2006), and the emerging metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) technologies (Feng et al. 2018a, b; Kobielska et al. 2018), and advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) (Feng et al. 2018a, b; Nidheesh et al. 2018), have long been used for the removal of toxic pollutants. However, these technologies have drawbacks such as toxic byproducts and high cost.

For a long time, adsorption has been considered an effective method for pollution control (Reddad et al. 2002; Bradl 2004). Adsorption techniques have significant advantages, such as profitability, availability, low cost (for example, the price of adsorption by vermiculite is only 20% of osmotic membrane technology), high efficiency (for example, the adsorption efficiency of kyanite for Cu(II) can reach 100%), and ease of operation in comparison with other techniques (Ajmal et al. 2001; Keng et al. 2014). Moreover, it offers simple operation and high efficiency (the maximum efficiency can reach 100%) in the removal of toxic heavy metals, even at trace levels (Musyoka et al. 2013). The key to adsorption technology is to prepare environmentally friendly, cheap and efficient adsorbents. A variety of adsorbents such as active carbon, zeolite, chitosan and clay have been studied and developed to remove toxic heavy metals from wastewater and soil (Strelko et al. 2004; Kosobucki et al. 2008).

Clay is a type of small particle existing naturally on the earth’s surface. It mainly consists of water, alumina, silica and weathered rocks (Murray 1991). Clay and clay composite materials have been developed as highly efficient adsorbents for heavy metal removal from aqueous solutions (Kasgoz et al. 2008; Mockovciakova et al. 2010). Clay materials also comprise exchangeable cations including Na+, Ca2+ and K+, making them efficient adsorbents (Srinivasan 2011). Most clay minerals are negatively charged (due to the substitution of Si4+ and Al3+ by other cations) and are extensively applied in the removal of heavy metal cations from wastewater in view of their high surface area and high cation exchange capacity (Yuan et al. 2013). Heavy metal adsorption by clay and clay composites consists of a series of complicated adsorption mechanisms, including ion exchange, surface complexation, and direct bonding of heavy metal cations to the surface of clays (Catalano and Brown 2005; Deng et al. 2006; Sari et al. 2007).

Furthermore, pretreatment of clays can improve the adsorption capacity of heavy metals. The process of clay pretreatment enhances the pore volume, surface area, and the amount of surface acid sites (Srimurali et al. 1998). In this way, clay materials can become more organophilic and hydrophobic, also enhancing the adsorption capacity for non-ionic organic substance after treatment or modification.

This article reviews the use of clay-based adsorbents including montmorillonite, attapulgite, halloysite and vermiculite, in recent years (2013–2017). Here, we summarize their compositions, adsorptive potential and efficiencies. In addition, we have classified the various clay minerals and evaluated their abilities to remove toxic heavy metals in wastewater. We emphasize clay and modified clays as environmentally safe adsorbents. The main purpose of this review is to help readers choose suitable adsorbents for the removal of target heavy metals as well as to facilitate the development of new adsorbents.

Properties and classification of clays

Clay minerals are mainly phyllosilicate minerals characterized by layered structural units made up of one or two tetrahedral silica sheets around an octahedral aluminum sheet (Velde 1995). They have particle sizes of less than 2 μm. The tetrahedral sheets have a Si2O6(OH)4 unit consisting of four hydroxyl groups surrounding every silicon atoms in a tetrahedron arrangement. By comparison, an octahedral arrangement consists of Fe, Mg or Al atoms surrounded by six hydroxyl or oxygen atoms, such as in the composition of Al2(OH)6 (Hendricks 1942; Gale et al. 1990).

Clays generally have three different inner surfaces, edges and surfaces-outer surfaces between the silicate layers. The interlayer and outer surfaces are susceptible to being changed during ion exchange and adsorption processes. Most clay minerals produce a small amount of net negative surface charge due to isomorphic substitution. Furthermore, particle edges of clay minerals may produce charges according to the suspension pH as a result of broken primary bonds, such as Si–O and Al–O (Leroueil et al. 1979).

Clays have a wide variety of physical properties, such as fineness of particles, hardness, good plasticity, associativity, appropriate shrinkage, high refractoriness and the capacity for surface decoration (Odoma et al. 2013). Clays have small particle sizes and high specific surface areas as a result of their complex porous structures, which facilitates physical and chemical interactions with dissolved species. These interactions result from crystallinity, electrostatic repulsion, adsorption and some cation exchange reactions. The high porous surface area indicates a high bonding force on the surface of the clays (Reichle 1986).

Based on the differences in internal layer structures, clays can be divided into two types: amorphous and crystalline (Chen et al. 2000). The crystalline clays possess crystal structures that can be divided into groups such as 1:1 type layer (kaolinite), 1:1 type tube (halloysite), 2:1 type layer (montmorillonite, smectite, vermiculite), the regular mixed-layer type (Chlorite group) and 2:1 type layer-chain type (attapulgite, sepiolite). Table 3 presents the chemical compositions of various natural clay minerals.

Kaolinite, chemically expressed as Al2Si2O5(OH)4, has the theoretical components of Al2O3 (39.53%), SiO2 (46.53%), and H2O (13.94%), in the case of the oxides. The chemical formula demonstrates that no substitution appears involving Si4+ substituted by Al3+ in the layer of tetrahedron and Al3+ substituted by other ions (Na+, K+, Zn2+, Mg2+, Ca2+, etc.) in the layer of octahedron. Kaolinite has a 1:1 layered structure comprised of a tetrahedral SiO4 sheet and an octahedral sheet with Al3+ as the octahedral cation. The hydroxyl groups situated below and above the two Al atoms make a central hexagonal distribution in one single plane in the range of the octahedral sheet. Furthermore, there is a small net negative charge at the broken edges on the kaolinite crystals, despite the neutral surface charge of kaolinite (Gruner 1932; Brindley and Robinson 1945). The applications of kaolinite clays involve ceramic, paper, medicine and cosmetics industries (Rhim et al. 2013; El-Sherbiny et al. 2015). Furthermore, the application of kaolinite in water treatment is growing rapidly in conjunction with other clay minerals, and H+ ions released from the edge of the layer structure in acidic environments promote the adsorption of heavy metal ions, such as Pb(II), Cu(II), Hg(II) and Cd(II), from aqueous matrices (Bhattacharyya and Gupta 2008). Some surface adsorption may also occur on the exposed tetrahedral or octahedral sheets (Fig. 1).

Reproduced from Bergaya et al. 2013 with permission

The structure of kaolinite.

Halloysite nanotubes are a kind of aluminosilicate clay [Al2Si2O5(OH)4·H2O with 1:1 layer] with nanotubular and hollow microstructures. The crystalline structure and phyllosilicate of halloysite nanotubes are formed by two main component parts: (1) sheets sharing an Al-O octahedral on the edge; (2) sheets sharing a Si–O tetrahedral at the corner. In the Al–O octahedral sheet, only two-thirds of the existing octahedra sites are filled by aluminum. The formation of the final lamellar structure builds up, containing the AlO6 octahedral and SiO4 tetrahedral. Moreover, the crystalline structure of halloysite nanotubes can be described as 1:1 phyllosilicate. The water molecules lie between the two continuous layers creating subtle differences in the relative oriented relationship between the adjacent layers, which might cause the differences in the symmetric characteristic of the ultimate layer structure (Du et al. 2010; Luo et al. 2010). Furthermore, there are reactive hydroxyl groups on the surface of tube, which can be modified by some organic compounds to increase the adsorption selectivity of heavy metal ions (Kiani 2014).

Bentonite is an aluminum phyllosilicate adsorbent mainly consisting of montmorillonite. It is a kind of sedimentary rock comprised largely of clays, with a typical 2:1 layer (smectites) structure and high concentrations of Na+, Ca2+ and Li+ ions located between the layers. The octahedral and tetrahedral sheets are in such a pattern that the tips of the tetrahedra in each silica sheet and one of the hydroxyl layers in the octahedral sheet constitute a single layer. The distance (d value) between the 2:1 layers is not a determined value because of the constant expansion of the layers. Laponite, a synthetic clay, has alumina silicate mineral layers with negative charges that make for an excellent cationic adsorption property due to its significant surface area, with a typical 2:1 layer structure and high concentrations of Li+ ion located between the layers (Bandeira et al. 2012; Cao et al. 2016). Montmorillonite is capable of immobilizing H2O molecules between the sheets, which results in remarkable expansion. The existence of ordinary impurities, such as mica, quartz, feldspar, calcite and organic matter, negatively affects the cation exchange capacity (CEC) and thermal stability of bentonites (Duman and Tunç 2009; Karimi and Salem 2011). Further, in acidic environments, the release of H+ ions from the edge of the structure causes metal adsorption from wastewaters onto the edges for ions like Cd(II), Zn(II) or Pb(II). Nevertheless, in order to get superior physical performances, such as thermal stability, and mechanical performances, the purification of bentonite is necessary. In this process, bentonite clays are usually purified by sedimentation and acid treatment, successively, before surface modification. According to the difference in exchangeable ions and mineral components, bentonite has a variety of commercial applications. The applications of bentonite clays involve raw materials and being treated by the methods of acid activation, soda activation, heat treatment and ion exchange (Karimi and Salem 2011). It can be used in the production of nanocomposites, decolorization of oils, remediation of soil and the synthesis of catalysts (Lenarda et al. 1994) (Fig. 2).

(Reproduced from Nasser et al. 2016 with permission)

The structure of bentonite (including the forms of laponite and montmorillonite).

Montmorillonites are unique smectitic clays, and they are widely distributed in the natural environment. Montmorillonite is a quite tender phyllosilicate, and its name comes from the location of its discovery, Montmorillon, France. It consists of plate-shaped particles with an average diameter of approximately 1 µm, and it is chemically represented as (Na, Ca)0.33 (Al, Mg)2Si4O10(OH)2·nH2O, which is formed by the change of volcanic ash (Frenkel 1974). Similarly, it also consists of three layers: one octahedral aluminum layer in the center surrounded by two tetrahedral silica layers. Interactions that take place between the sheets generally occur through –OH groups in the octahedral layer and the tips of the tetrahedral layer. Montmorillonite is also a kind of swelling clay because of the expanding of the lattice caused by polar molecules, including water. In addition, interlamellar spacing may fluctuate due to cations changing between the silicate sheets (Winchell 1945). Montmorillonite clay has been used in many applications for many years (de Paiva et al. 2008). Due to its significant biological activity, montmorillonite clay is widely used in the field of treatment of tropical diseases. Acid-activated montmorillonite clay has been widely used in the food industry working as bleach. Due to its large surface area and expandable layered structure, the excellent adsorption capacity of modified montmorillonite has been used to remove various heavy metals in aqueous solution, particularly mercury ions (Wang et al. 2014) (Fig. 3).

(Reproduced from Bhattacharyya and Gupta 2008 with permission)

The structure of montmorillonite.

Vermiculite is a common clay mineral, and it is found in layered silicate, with a structure of 2:1 aluminosilicate. The 2:1 layer structure consists of a tetrahedral sheet of silica and two sheets of MgO2(OH)4 octahedra, in which silicon is partially replaced by aluminum, creating a stable mica stack. Exchangeable cations located in the interlayer space, such as K+, Na+, Ca2+ and Mg2+, compensate for the positive charge deficiency in the parallel 2:1 layers. In this way, the two layers are combined, and the structure is generally known as 2:1 layered silicate (Hendricks and Jefferson 1938; Shirozu and Bailey 1966). Vermiculite can be divided into two forms: unexpanded vermiculite and expanded vermiculite. Unexpanded vermiculite refers to raw vermiculite without burning processing step, and after burning processing step, expanded vermiculite is produced. The volume of expanded vermiculite increases after burning processing step in comparison with unexpanded vermiculite. Vermiculite has a large internal surface area, high negative charge on the silicate layers, and higher cation exchange capacity at 120–160 mequiv./100 g in comparison with other 2:1 layered silicate (Xu and Boyd 1994).

Attapulgite clay is a crystalline hydrated aluminum-magnesium silicate mineral, as a rare non-metallic mineral resource but not very well known on its structure and component (Liu 2007). The important element in the structure is the hornblende double silica chain parallel to the c axis in the long direction (Fig. 4). Parallel to the c axis and linking together with the oxygen atoms on their longitudinal edges, the double silica chains constitute the structure of attapulgite. The vertices of the tetrahedron point to the opposite direction in a continuous chain. A special kind of double ribbed layer, with double rows of tetrahedral apexes vertices, is formed at the bottom and top of the layer in the alternating spacing. Like the double silica chain, the water molecule chains are in parallel with the c axis, filling up the interspaces between the amphibolite chains. In this way, the substitutions of silicon by aluminum are considered impossible. From the perspective of performance, attapulgite has a variety of excellent properties as a superior colloid, catalyst, adsorption material, and physicochemical filler due to its unique fiber-crystal structure (Ruiz-Hitzky et al. 2005; Lv et al. 2017). In addition, attapulgite has been extensively used in the treatment of wastewater. Moreover, attapulgite has the advantages of large specific surface area, good compatibility with microorganisms and strong adsorption capacity for heavy metal ions (Wang and Wang 2016).

(Reproduced from Pan et al. 2011 with permission)

Structure of attapulgite projected on the (001) plane.

Adsorption properties of various modified clays

For the purpose of enhancing the adsorption capacity of raw clay minerals, various modification methods have been used over the past few decades. Different treatment methods can remove various heavy metals effectively. Many comparative studies have revealed that modification can effectively increase the adsorption capacity of clay materials. Here, we present our research progress on heavy metal removal using clay minerals in recent years (2013–2017), and we highlight the significant findings in adsorption mechanism studies.

Heavy metal removal by 1:1 type clays

Sb(V) and Cr(VI) removal by modified halloysite nanotubes

In this work, a new adsorbent was successfully synthesized from Fe3O4 nanoparticles growing on halloysite nanotubes (HNTs), followed by succedent decoration by silane coupling agents. The halloysite nanotubes/Fe3O4 composite modified by anilino-methyl-triethoxysilane (KH-42) exhibited high adsorption capacity for Cr(VI) and simultaneous removal of Sb(V) and Cr(VI). Furthermore, the maximum removal efficiency for Sb(V) increased from 67.0% in single-solute system) to 98.9% in bi-solute system, indicating that the existence of Cr(VI) enhanced the removal of Sb(V) by the m-halloysite nanotubes/Fe3O4 adsorbent. This work showed m-halloysite nanotubes/Fe3O4 has great potential in treating wastewater with coexisting heavy metal ions, such as Sb(V) and Cr(VI) (Zhu et al. 2017a, b).

Preparation of m-halloysite nanotubes/Fe3O4 nanocomposites

The preparation of m-halloysite nanotubes/Fe3O4 composites was based on the following steps: (1) clay mineral cation exchange sites were activated and saturated by hydrochloric acid and Fe(III); (2) Fe3O4 was immobilized on the clay surface by in situ co-precipitation of Fe(II) and Fe(III) species; and (3) condensation reactions were used to graft the silanes onto the clay surfaces.

Characterization of m-halloysite nanotubes/Fe3O4 nanocomposites

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of halloysite nanotubes, halloysite nanotubes/Fe3O4, and m-halloysite nanotubes/Fe3O4 are shown in Fig. 5a. The diffraction peaks at 35.09°, 24.85°, 20.14°, and 12.00° corresponded to the d values of 0.254 nm, 0.358 nm, 0.411 nm and 0.733 nm, respectively. These peaks were indexed to halloysite nanotubes. New diffraction peaks for halloysite nanotubes/Fe3O4 at 62.70°, 57.17°, 43.23°, 35.54°, and 30.13° corresponded to the d values of 0.161 nm, 0.209 nm, 0.252 nm and 0.296 nm, and these peaks were identified as Fe3O4, according to JCPDS Card No. 19-0629. These results reveal that magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles were successfully immobilized on the surfaces of halloysite nanotubes (Zhang et al. 2008). In addition, the characteristic diffraction peaks of Fe3O4 and halloysite nanotubes were retained in the m-halloysite nanotubes/Fe3O4 nanocomposites, indicating that Fe3O4 and halloysite structures were reserved in the preparation process of m-halloysite nanotubes/Fe3O4 nanocomposites.

a The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns, the characteristic diffraction peaks of Fe3O4 and halloysite nanotubes were retained in the m-halloysite nanotubes/Fe3O4 nanocomposites, indicating that Fe3O4 and halloysite structures were reserved in the preparation process of m-halloysite nanotubes/Fe3O4 nanocomposites; b thermo gravimetric analysis (TG) and derivative thermogravimetric (DTG) curves, the mass loss differences of halloysite, halloysite nanotubes/Fe3O4, and m-halloysite nanotubes/Fe3O4 nanocomposites indicate the clay surface was decorated with the grafting agents; c Attenuated total reflectance-Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR) spectrum of halloysite nanotubes samples, the changes of peak reveal the successful grafting of the silane coupling agent onto the surface of halloysite nanotubes; d relationship between pH and zeta potential for halloysite nanotubes samples, the characterization indicates that magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles and KH-42 have been successfully immobilized on the surfaces of halloysite nanotubes (Zhu et al. 2017a, b)

The results of thermo gravimetric analysis (TGA) and derivative thermogravimetric (DTG) curves are shown in Fig. 5b. The process of devolatilization for halloysite nanotubes and halloysite nanotubes/Fe3O4 showed similar curves for DTG. And the first-step mass loss in the temperature (30–150 °C) was associated with the evaporation process of adsorbed water on the surfaces. Moreover, the mass loss at 490 °C was attributed to the dihydroxylation process of structural aluminol groups in halloysite nanotubes (Xie et al. 2011). The mass loss in the temperature (30–150 °C), in comparison with halloysite nanotubes/Fe3O4, was decreased for the modified samples, indicating that water adsorbed on the surface of the clay was replaced by the grafting agents (Guangyan et al. 2014). In the temperature of 200–550 °C, the increased mass loss for m-halloysite nanotubes/Fe3O4 was attributed to the decomposition process of the silane grafted onto the surface, including the internal surfaces with Al–OH and the external surfaces with Si/Al–OH (Duquesne et al. 2007).

Attenuated total reflectance-Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR) spectrum of raw halloysite nanotubes is shown in Fig. 5c. The absorption peaks at 3711 and 3642 cm−1 were attributed to –OH stretching of Al-OH groups, and the peak at 922 cm−1 was caused by -OH deformation of the above –OH groups. All of the above peaks appeared in the ATR-FTIR spectra of halloysite nanotubes/Fe3O4. It is remarkable that the vibration peaks at 3060 and 3396 cm−1 of m-halloysite nanotubes/Fe3O4 are newly discovered, and these peaks were ascribed to C–H asymmetric vibrations and N–H asymmetric stretching (Hong et al. 2008). In addition, the peak at 1613 cm−1 was ascribed to the stretching vibration of C=C in the benzene ring. The 1516 cm−1 peak was attributed to the N–H curve vibration (Ma et al. 2006). Furthermore, the strength of peak (Al–OH) decreased, which was due to the interaction between KH-42 and Al–OH (Luo et al. 2011). These results reveal the successful grafting of the silane coupling agent onto the surface of halloysite nanotubes.

The relative affinity of the composite for adsorption is closely related to the surface charge, and the surface charge mainly depends on the pH of water environment. As a function of solution pH, the zeta potentials of m-halloysite nanotubes/Fe3O4, halloysite nanotubes/Fe3O4, and halloysite nanotubes are exhibited in Fig. 5d. The surface zeta potentials for halloysite nanotubes/Fe3O4 and halloysite nanotubes are negative from the pH range of 2.0–10.0, which can be ascribed to the –OH groups present on the surface of halloysite nanotubes/Fe3O4 and halloysite nanotubes (Huang et al. 2016). After modification by KH-42 silane coupling agent, the Zeta potential values turn much more positive. Moreover, once the pH was lower than 4, a positively charged surface was observed, which can be ascribed to the protonation of the amine groups (Luo et al. 2011). This characterization indicates that magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles and KH-42 have been successfully immobilized on the surfaces of halloysite nanotubes.

Simultaneous adsorption of Sb(V) and Cr(VI) by m-halloysite nanotubes/Fe3O4

As shown in Fig. 6a, the removal rate of Sb(V) (RSb) in the single-solute system is obviously lower than that in the bi-solute system, further demonstrating the adsorption capability of m-halloysite nanotubes/Fe3O4 for Sb(V) and Cr(VI). As shown in Fig. 6b, the removal of Sb(V) and Cr(VI) decreased with increasing solution pH. As shown in Fig. 6c, d, Langmuir and Freundlich isotherm models were used to discuss the adsorption equilibrium for Cr(VI). The correlation coefficient values (R2) indicate that in order to describe the adsorption process better, the Langmuir model is more appropriate than the Freundlich, which suggests that the Cr(VI) adsorption type on the surface of m-halloysite nanotubes/Fe3O4 belongs to monolayer adsorption.

a The removal rate of Cr(VI) and Sb(V) in the bi-solute system, the removal rate of Sb(V) (RSb) in the single-solute system is obviously lower than that in the bi-solute system, further demonstrating the adsorption capability of m-halloysite nanotubes/Fe3O4 for Sb(V) and Cr(VI); b the effect of initial pH on the adsorption of Cr(VI) or Sb(V) by m-halloysite nanotubes/Fe3O4, showing the removal of Sb(V) and Cr(VI) decrease with increasing solution pH; c Langmuir plot and d Freundlich plot for the removal of Cr(VI) by m-halloysite nanotubes/Fe3O4, suggesting the Langmuir model is more appropriate than the Freundlich to describe the adsorption process (Zhu et al. 2017a, b)

Potential adsorption mechanisms

Electrostatic attraction provides initial driving force for Cr(VI) to bind onto the surfaces of m-halloysite nanotubes/Fe3O4 (Eq. 1). Inner-sphere complexation is another key factor for Cr(VI) and Sb(V) adsorption (Eqs. 2–5). For inner-sphere complexation, Cr(VI) are first adsorbed onto the surface of m-halloysite nanotubes/Fe3O4 adsorbents by functional groups and anion-π interactions (Eq. 2), and then H3SbO4 is attached onto the surface of m-halloysite nanotubes/Fe3O4 adsorbents by the Cr(VI)–O–Sb(V) interaction (Eq 3). Furthermore, Sb(V) and Cr(VI) ions could form Cr(VI)–O–Sb(V) complexes in aqueous solution. In that case, Cr(VI)–O–Sb(V) complexes are adsorbed by complexation reactions (Eqs. 4, 5).

Summary

To improve its adsorption capacity and solid-liquid separation property, the surface of halloysite is decorated by Fe3O4 nanoparticles and modified with silane coupling agents successfully. The halloysite nanotubes/Fe3O4 composite modified by KH-42 exhibits the highest capacity for Cr(VI) adsorption; the Cr(VI) removal efficiency achieves to 100% when the initial contention of Cr(VI) is < 40 mg/L. Results obtained from ATR-FTIR and XPS measurements confirm the formation of inner-sphere complexes between Cr(VI) and functional groups of m-halloysite nanotubes/Fe3O4. In the bi-solute system, part of Cr(VI) ions are primarily adsorbed onto m-halloysite nanotubes/Fe3O4, and then form Cr(VI)–O–Sb(V) with the freedom of Sb(V). In addition, partial Cr(VI) and Sb(V) ions form Cr(VI)–O–Sb(V), then adsorbed onto m-halloysite nanotubes/Fe3O4 by complexation. It is concluded that m-halloysite nanotubes/Fe3O4 could be used as a low cost, easy separation, and relatively effective adsorbent for simultaneously removing Cr(VI) and Sb(V) from industrial wastewater and natural surface water.

Heavy metal removal by 2:1 type layer clays

Synthesis of functionalized modified montmorillonite/carbon nanocomposites

The montmorillonite/carbon nanocomposites were prepared by a one-pot process of hydrothermal carbonization, regarding d-glucose as the carbon nanoparticle precursor. The as-prepared nanocomposite montmorillonite/carbon provided a foundation for grafting the following functionalized groups: –COOH, –OH and –NH2. For montmorillonite/carbon-COOH, a mixture of H2O2 solution and montmorillonite/carbon was stirred vigorously. Ultimately, a black powder, referred to as montmorillonite/carbon-COOH composite, was obtained after washing and drying. As for the montmorillonite/carbon-OH composites, we added montmorillonite/carbon material into the NaOH solution and transferred it to a high temperature hydrothermal device at 150 °C. Montmorillonite/carbon-NH2 was synthetized by mixing montmorillonite/carbon and NaNO2 with ethane diamine solution, followed by sonication and microwave digestion. According to the above methods, we preliminarily introduced three different organic functional groups (–COOH, –OH and –NH2) onto the surface of montmorillonite/carbon nanocomposites.

Characterization of modified montmorillonite/carbon nanocomposites

N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms and distributions of pore size for montmorillonite and montmorillonite/carbon composites are shown in Fig. 7a, b. The surface area of montmorillonite/carbon was larger than that of Na+-montmorillonite, indicating the carbonaceous nanoparticles prepared on montmorillonite contribute to the specific surface area. The increase in N2 adsorption capacity at low pressure suggests that there are a small amount of micropores in montmorillonite/carbon, and the remarkable hysteresis loops at relative pressures (0.4–0.8) indicate the existence of mesoporous structures (Sing et al. 1985; Bakandritsos et al. 2004). Furthermore, the pore size peak of Na+-montmorillonite is 4.0 nm, while the as-prepared montmorillonite/carbon inherits the 4 nm-pore distribution for montmorillonite (Fig. 7b). It is worth noting that a new peak at 7.8 nm appears in montmorillonite/carbon, which can be attributed to the carbon particles loaded onto montmorillonite. The above results suggest that the carbonaceous nanoparticles are one part of montmorillonite/carbon, and the carbonaceous nanoparticles have significant impact on the specific surface area and porosity.

a N2 sorption isotherm, The increase in N2 adsorption capacity at low pressure suggests that there are a small amount of micropores in montmorillonite/carbon, and the remarkable hysteresis loops at relative pressures (0.4–0.8) indicate the existence of mesoporous structures; b pore size distribution of montmorillonite/carbon and montmorillonite, the pore size peak of montmorillonite is 4.0 nm, while the as-prepared montmorillonite/carbon inherits the 4 nm-pore distribution for montmorillonite, suggesting that the carbonaceous nanoparticles are one part of montmorillonite/carbon, and the carbonaceous nanoparticles have significant impact on the specific surface area and porosity; c FTIR of montmorillonite/carbon and montmorillonite; d FTIR of functionalized montmorillonite/carbon composites, confirming that the designated functional groups have successfully modified the structure of montmorillonite/carbon composites (Zhu et al. 2017a, b)

Infrared spectroscopy was adopted for the structural analysis of three functionalized montmorillonite/carbon composites, montmorillonite/carbon and montmorillonite (Fig. 7c, d). The characteristic band of montmorillonite at 3635 cm−1 was ascribed to the structural –OH group vibrational stretching. Some new peaks appeared in the spectrum of montmorillonite/carbon after the hydrothermal carbonization process. The peak at 2941 cm−1 was attributed to the vibration of C–H groups. And peaks at 1623 and 1707 cm−1 were ascribed to C=C and C=O stretching vibrations (Demir-Cakan et al. 2009). As the results shown, the functional carbonaceous nanoparticles had been partially loaded onto the surfaces of montmorillonite. The results suggest that montmorillonite is partially modified by the functional carbonaceous species. In comparison with montmorillonite/carbon, the strong peaks of montmorillonite/carbon-COOH at 1714 and 3400 cm−1, correspond to the vibrations of C=O groups and the stretching vibrations of O–H groups, respectively. And montmorillonite/carbon-OH exhibited stronger peaks at 3400 cm−1, 1585 cm−1 and 1402 cm−1 in comparison with montmorillonite/carbon. As for montmorillonite/carbon-NH2 composite, the peaks at 1448 cm−1, 1638 cm−1 and 3307 cm−1 were attributed to the vibrations of C–N groups, bend vibrations and stretching vibrations of N–H groups (Chen et al. 2014), respectively. The above results confirm that the designated functional groups have successfully modified the structure of montmorillonite/carbon composites.

Figure 8a demonstrates the X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of montmorillonite/carbon composites and montmorillonite. The basal spacing of clays is calculated according to the following Bragg equation (Eq 6).

where θ represents the incident angle, and d(001) stands for the clay basal spacing. As shown in Fig. 8a, the basal spacing of the prepared montmorillonite/carbon increased to ~ 15.06 from ~ 12.3 of montmorillonite, which indicates that subtracting the thickness of one smectite layer (9.6 Å), the remaining interlayer distance of clay was 5.1 Å. Moreover, the results confirm that the clay interlayers should be inserted by a few carbon clusters (~5 Å in size) (Anadao et al. 2011).

a The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of montmorillonite/carbon and montmorillonite, the basal spacing of the prepared montmorillonite/carbon increased to ~ 15.06 from ~ 12.3 of montmorillonite, which indicates that subtracting the thickness of one smectite layer (9.6 Å), the remaining interlayer distance of clay was 5.1 Å, confirming that the clay interlayers should be inserted by a few carbon clusters; b effect on the adsorption of Pb(II) by solution pH, the order of adsorption capacity is as follows: montmorillonite/carbon-COOH > montmorillonite/carbon-OH > montmorillonite/carbon-NH2 > montmorillonite/carbon, the Pb(II) adsorption capacity of all adsorbent systems increased with the increase in pH from 2 to 5; c Pb(II) adsorption isotherm of montmorillonite/carbon-COOH under different temperatures, the Langmuir model can describe the adsorption process of Pb(II) much better than the Freundlich model according to the correlation coefficient values (R2), demonstrating the presence of maximum monolayer surface coverage and constant adsorption site energy; d effect of contact time on the adsorption capacity for Pb(II), the adsorption rate for Pb(II) appeared a rapid increasing reaching 94.66 mg g−1 in the first 40 min and remained stagnant at 98.36 mg g−1 owing to the presence of a large amount of surface active groups at the first 40 min (Zhu et al. 2017a, b)

Batch adsorption experiments

Experimental research of adsorption was adopted at different pH values to determine the influence of solution pH on removing Pb(II) by functionalized montmorillonite/carbon, montmorillonite/carbon and montmorillonite. Figure 8b shows the relationship between pH of solution and adsorption capacities of different adsorbents. As a result of the addition of more adsorption sites and functional groups, the adsorption capacities for Pb(II) of functionalized montmorillonite/carbon increased obviously after montmorillonite/carbon modification (Zhang et al. 2015). The order of adsorption capacity is as follows: montmorillonite/carbon-COOH > montmorillonite/carbon-OH > montmorillonite/carbon-NH2 > montmorillonite/carbon. In addition, the Pb(II) adsorption capacity of all adsorbent systems increased with the increase in pH from 2 to 5. The complexations between Pb(II) and different functional groups (–NH2, –COOH and –OH groups) work for the different adsorption effects with the three adsorbents.

The Pb(II) adsorption capacity by montmorillonite/carbon-COOH increased obviously with the increase in initial concentration (Fig. 8c). For Pb(II) concentrations greater than 100 mg L−1, there is little change in amount of Pb(II) adsorption. According to the correlation coefficient values (R2), the Langmuir model can describe the adsorption process of Pb(II) much better than the Freundlich model, which demonstrates the presence of maximum monolayer surface coverage and constant adsorption site energy. The theoretic adsorption capacity of montmorillonite/carbon-COOH for Pb(II) reached 247.85 mg g−1, much higher than most of the carbon-based adsorbents, such as carbon nanotubes and modified activated carbon (Kadirvelu et al. 2000; Li et al. 2005; Gao et al. 2009; Chakraborty et al. 2011).

In practical application, the adsorption rate is another key factor in the design of adsorbents. As shown in Fig. 8d, the adsorption rate for Pb(II) appeared a rapid increasing reaching 94.66 mg g−1 in the first 40 min and remained stagnant at 98.36 mg g−1. Owing to the presence of a large amount of surface active groups, the initial adsorption rate for Pb(II) was high. On the contrary, it is because of the gradual consuming of surface adsorption sites that the Pb(II) adsorption rate after 40 min became slow, and during this period, the state of charge balance formed on the surface of adsorbent (Luo et al. 2011). According to Table 4, in comparison with the pseudo-first-order model, the pseudo-second-order model is more suitable for describing the process of Pb(II) adsorption due to a higher correlation coefficient (R2). Furthermore, the Qe (experimental adsorption capacity at equilibrium) approximates to Qe,c (calculated value by kinetic equation) of pseudo-second-order model. Therefore, chemical adsorption is responsible for the process of Pb(II) adsorption by means of sharing electrons between Pb(II) and adsorbent and forming covalent forces (Baydemir et al. 2007).

Summary

Montmorillonite/carbon and functionalized montmorillonite/carbon nanocomposites were synthesized by a one-pot hydrothermal process. The spectroscopic characteristic results confirmed that the montmorillonite were decorated by functional carbonaceous species successfully. Their adsorption properties were evaluated by the Pb(II) removal. Consequently, Pb(II) adsorption onto m-montmorillonite/carbon was strongly affected by the surface functional groups. The Pb(II) adsorption capacity follows the order carboxylated montmorillonite/carbon > hydroxylated montmorillonite/carbon > aminated montmorillonite/carbon > montmorillonite/carbon. Mechanistic study implies that the complexation of Pb(II) with functional groups on the surface of adsorbents plays an important role in its removal. All of those results indicate that the functionalized montmorillonite/carbon composites have excellent adsorption properties for removing Pb(II) from contaminated water.

Synthesis and properties of modified bentonite

Previous studies have demonstrated that bentonite can be adopted as a filler in the matrices of polymer due to the strong interactions between the Si–O–Si groups of bentonite and functional groups in polymer matrices, including –OH, –COOH, –NH2 and N-acetyl glucosamine units (Darder et al. 2005). In this work, we combined bentonite clay with the chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol) (CTS-PVA) polymer matrix and synthesized a new type of chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/bentonite (CTS-PVA/BT) adsorbent.

Preparation of chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/bentonite nanocomposites

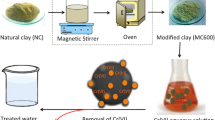

Due to the presence of impurities, including illite, kaolinite, feldspar quartz and carbonate, the pretreatment of raw bentonite is necessary to optimize the chemical and mechanical properties of the nanocomposites. Scheme 1 shows the process of pretreatment adopted in this work.

We prepared a series of chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/bentonite composites with different bentonite contents by cross-linking and interpenetrating polymer network technologies. As shown in Scheme 2, we added poly(vinyl alcohol) aqueous solution and a certain amount of bentonite into the chitosan solution. Next, we poured glutaraldehyde solution into the mixture. The mixture underwent freeze-thawed cycle for three times, and the nanocomposites were developed.

Pretreatment process of raw bentonite (Wang et al. 2014)

Characterization of chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/bentonite nanocomposites

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) photographs of the chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/bentonite adsorbents with different bentonite contents are exhibited in Fig. 9. The surface topography of the chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/bentonite adsorbent is apparently different from that of chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol). After introduced bentonite, chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol) produces many slit pleats and pores, compared to the tight bentonite surface. The surfaces of chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/bentonite, with the increase in bentonite content from 1 to 7%, seem looser and more porous than that of chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol), and no apparent protuberances were observed. With further increasing the bentonite content (beyond 7%), the protuberances become increasingly evident which can be attributed to the accumulation of clay tactoids due to the aggregation of clay tactoids.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) photographs of chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/bentonite adsorbent with different bentonite contents, surfaces of chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/bentonite become looser and more porous than that of chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol) with the increase in bentonite content from 1 to 7%; with further increasing the bentonite content (beyond 7%), the protuberances become increasingly evident which can be attributed to the accumulation of clay tactoids due to the aggregation of clay tactoids (Wang et al. 2014)

As shown in Fig. 10, N2 adsorption isotherms reveal the pore structure and specific surface area of the chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/bentonite adsorbent. Based on the classification of IUPAC, the adsorption isotherms fit type IV characteristics, suggesting that the chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/bentonite adsorbent belong to the representative mesoporous material. The hysteresis effect shows the typical H2 characteristics of interstices pores, which can be seen clearly under the circumstance of mesopore filling. With the increase in bentonite content from 1 to 50%, the hysteresis loop transfers to higher relative pressure, indicating the presence of larger mesopores. The Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) analyses for surface area of chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/bentonite adsorbent varied from 11.07 to 14.72 m2/g, with the total pore volume ranging from 0.0168 to 0.0394 cm3/g. The small specific surface area can be attributed to the structure of tight cumulating; in addition, the pore structure with low volume may be due to closed particles’ blocking effect.

N2 adsorption isotherms of chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/bentonite adsorbent with different bentonite contents, with the increase in bentonite content from 1 to 50%, the hysteresis loop transfers to higher relative pressure, indicating the presence of larger mesopores; the small specific surface area can be attributed to the structure of tight cumulating; in addition, the pore structure with low volume may be due to closed particles’ blocking effect (Wang et al. 2014)

The Derivative thermogravimetric analysis (DTG) and the thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) curves were used to study the thermal decomposition properties of the chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/bentonite adsorbent. As shown in Fig. 11, two degradation stages are observed in both DTG and DTA curves. The first stage of mass reduction occurred at 110 °C, attributed to the evaporation of the residual water in the adsorbent. The second weight loss stage occurred between 250 and 540 °C, caused by the thermal decomposition of chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/bentonite. Furthermore, with the increase in bentonite content, the weight loss peaks in the DTG curves shifted to higher temperature ranges, suggesting the introduction of bentonite strengthened the thermal stability of the composites.

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) (a) curves and Derivative thermogravimetric analysis (DTG) (b) curves of chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/bentonite composites with different bentonite contents, with the increase in bentonite content, the weight loss peaks in the DTG curves shifted to higher temperature ranges, suggesting the introduction of bentonite strengthened the thermal stability of the composites (Wang et al. 2014)

Heavy metal adsorption properties of chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/bentonite adsorbent

Figure 12 shows the heavy metal adsorption capacities at equilibrium with different bentonite contents containing the individual species of heavy metal in acetic salt solutions. The Hg(II) equilibrium adsorption capacity of chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/bentonite was far higher than that of Pb(II), Cd(II) and Cu(II), which indicates the synthetic chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/bentonite may exhibit special selective adsorption for Hg(II). With the bentonite contents of 50, 30, 10 and 0%, the Hg(II) adsorption capacities of chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/bentonite were 360.73, 392.19, 455.12 and 460.18 mg/g, respectively. Under the same conditions, we observed that the Hg(II) adsorption capacity of the pretreated bentonite was 11.20 mg/g. If bentonite clay particles were simply distributed in the polymer matrix of chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol), the adsorption capacities of chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/bentonite should be equivalent of the total adsorption capacity of chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol) polymer and bentonite, i.e., 235.69, 325.46 and 415.28 mg/g for chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/bentonite with the bentonite contents of 50, 30 and 10%. The experimental data are far higher than the calculated values, indicating the nanocomposite is not just simple mixture. In addition, the bentonite clay took part in the preparation of chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/bentonite and increased the Hg(II) adsorption capacity to a certain extent.

Adsorption capacities of chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/bentonite for different heavy metals, the Hg(II) equilibrium adsorption capacity of chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/bentonite was far higher than that of Pb(II), Cd(II) and Cu(II), which indicates the synthetic chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/bentonite may exhibit special selective adsorption for Hg(II) (Wang et al. 2014)

To further confirm the Hg(II) adsorption selectivity of the chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/bentonite adsorbent, multi-component adsorption experiments were carried out. The distribution coefficient (Kd) represents the adsorption affinity of the heavy metals for the adsorbent, which can a useful tool to research the retention and mobility of metal-cation in adsorbent system (Gomes et al. 2001). In the presence of other heavy metal ions, the selectivity coefficient (k) of the chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/bentonite adsorbent for Hg(II) is determined using the following equation:

where Kd(Hg) and Kd(M) stand for the distribution coefficients for Hg(II) and another heavy metal ion, respectively. The k values are presented in Table 5. With increasing bentonite content, the Hg(II) selectivity coefficient of the chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/bentonite adsorbent increased, indicating that the Hg(II) adsorption selectivity of chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/bentonite can be significantly improved by the introduction of bentonite clay. It can be considered as the most meaningful finding to support the use of bentonite clay in the polymer matrix of chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol).

Summary

The chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/bentonite nanocomposites have been synthesized by the combination of bentonite and the chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol) polymer matrix. The chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/bentonite nanocomposites possess a mesoporous structure, excellent adsorption capacity and selectivity for Hg(II) ions. The bentonite content greatly affects the microstructure of the nanocomposites and their adsorption selectivity for Hg(II) ions. In addition, the selectivity coefficient of the nanocomposites toward Hg(II) ions increases with increasing the bentonite content.

Synthesis and properties of modified vermiculite

Preparation of g-polyacrylamide/vermiculite nanocomposites

First, the raw vermiculite was acid-treated. Next, the a-Verm (acid-treated vermiculite) was organically modified as follows: 3.0 g Verm, 1.0 mL water and 3.0 mL 3-(triethoxysilyl)propyl methacrylate were added to 100 mL toluene with ultrasonic agitation for 30 min. The final TEPM-modified acid vermiculite was abbreviated as OVerm. OVerm dispersed into a three-neck flask with a certain amount of the toluene solution and stirred for 10 min, followed by the addition of acrylamide monomer and 2, 2-azobisisobutyronitrile initiator. The obtained sample was denoted as polyacrylamide/vermiculite (PAM/OVerm). Triethylenetetramine was applied to introduce more –NH2 to the long chain of polyacrylamide. PAM/OVerm was dispersed in a flask containing distilled water. The pH of the mixture was adjusted with sodium hydroxide or hydrochloric acid solution. During stirring at a specified temperature, formaldehyde and triethylenetetramine were added. The obtained adsorbent material is abbreviated as g-polyacrylamide/vermiculite (g-PAM/OVerm).

Characterization of g-polyacrylamide/vermiculite nanocomposites

The derivative thermogravimetric analysis (DTG) curves of vermiculite samples (Fig. 13b) had an endothermic peak at about 91.6 °C, implying a loss of moisture. The TEPM-modified vermiculite (OVerm) exhibited an endothermic peak at 312.4 °C, which was attributed to the decomposition of the TEPM. Moreover, the derivative thermogravimetric analysis curves of polyacrylamide/vermiculite and g-polyacrylamide/vermiculite also had an endothermic peak at 354 °C, which was largely caused by the decomposition of polyacrylamide. Moreover, the total mass loss of acid-modified vermiculite, TEPM-modified vermiculite, polyacrylamide/vermiculite and g-polyacrylamide/vermiculite at 25–750 °C were 11.14, 19.18, 24.28 and 26.11%, respectively (Fig. 13a). The mass loss demonstrates that the number of organic groups, including –C–H and –NH2, remaining in the samples per unit mass increased as the modification and grafting reactions proceeded. In other words, the thermogravimetric analysis and Derivative thermogravimetric analysis results confirmed the presence of the polyacrylamide modification and –NH2 grafting reaction on vermiculite.

Thermogravimetric analysis (TG) (a) and Derivative thermogravimetric analysis (DTG) (b) curves of acid-treated vermiculite (a-Verm), TEPM-modified vermiculite (OVerm), polyacrylamide/vermiculite (PAM/OVerm) and g-polyacrylamide/vermiculite (g-PAM/OVerm), the mass loss demonstrates that the number of organic groups, including –C–H and –NH2, remaining in the samples per unit mass increased as the modification and grafting reactions proceeded

The nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms for a series of vermiculite samples (Fig. 14) exhibit type II isotherms, with a hysteresis loop, based on IUPAC classification. This indicates a large mesoporous distribution, with pore size between 2 and 50 nm (Valente et al. 2009). The hysteresis loops is type H3, in connection with the slit-shaped pores or plate-like particles. The isotherm type for all vermiculite samples in the series is the same. The surface area (SBET) increased after acid modification. Raw vermiculite and acid-treated vermiculite had a SBET of 27.76 and 694.24 m2/g, respectively. In addition, the surface areas of TEPM-modified vermiculite, polyacrylamide/vermiculite and g-polyacrylamide/vermiculite were 396.46 m2/g, 247.37 m2/g and 201.84 m2/g, respectively. SBET decreased with the further modification and grafting reaction. The smaller SBET of functionalized Verm was a consequence of the coverage of the silane coupling agent and polyacrylamide, which reduced the adsorption of N2 (Table 6).

N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms of vermiculite (Raw Verm), acid-treated vermiculite (a-Verm), TEPM-modified vermiculite (OVerm), polyacrylamide/vermiculite (PAM/OVerm) and g-polyacrylamide/vermiculite (g-PAM/OVerm), exhibiting type II isotherms with a hysteresis loop based on IUPAC classification, and the isotherm type for all vermiculite samples in the series is the same

Adsorption of Pb(II) by g-polyacrylamide/vermiculite nanocomposites

The effects of time on the adsorption of Pb(II) by g-polyacrylamide/vermiculite are given in Fig. 15a, b. The adsorption rate was very fast during the first 20 min, during which the removal of Pb(II) was 120.1 mg g−1. After that, the adsorption rate was very slow, and the adsorption equilibrium gradually completed within 60 min for Pb(II). From Table 7, the correlation coefficient value (r2) of the pseudo-first-order model was relatively lower, showing a poor fit to the adsorption data. Nevertheless, the correlation coefficient for the pseudo-second-order was greater than 0.995. Meanwhile, the calculated qe value was also very close to the experimental data, according to pseudo-second-order kinetics. The adsorption dynamics analysis suggests that the Pb(II) adsorption fit the pseudo-second-order kinetics model. Therefore, the pseudo-second-order mechanism was predominant in the process of Pb(II) removal by g-polyacrylamide/vermiculite, which corresponded to the rate-controlling step of chemical adsorption (Ho and McKay 1999).

The pseudo-second-order kinetics (a), the pseudo-first-order kinetics (b), the adsorption rate was very fast during the first 20 min, during which the removal of Pb(II) was 120.1 mg g−1; after that, the adsorption rate was very slow, and the adsorption equilibrium gradually completed within 60 min for Pb(II), Langmuir plot (c) and Freundlich plot (d) for the adsorption of Pb(II) by g-polyacrylamide/vermiculite, Pb(II) adsorption by g-polyacrylamide/vermiculite increased with increasing initial Pb(II) concentrations, demonstrating the Langmuir model can represent the adsorption isotherm results better than Freundlich

Langmuir and Freundlich isotherm models were carried out to explore the Pb(II) adsorption equilibrium. The results are shown in Fig. 15c, d and Table 8. In general, Pb(II) adsorption by g-polyacrylamide/vermiculite increased with increasing initial Pb(II) concentrations. Additionally, the correlation coefficient (r2) values demonstrate the Langmuir model can represent the adsorption isotherm results better than Freundlich. This indicates that monolayer adsorption mechanism works for the removal of Pb(II) because the active sites distribute evenly on the surface of g-polyacrylamide/vermiculite (Vadivelan and Kumar 2005). Based on the Langmuir equation, the theoretical maximum adsorption capacity (qm) of Pb(II) on g-polyacrylamide/vermiculite is 219.4 mg g−1.

The reutilization of g-polyacrylamide/vermiculite on Pb(II) adsorption was performed in a batch experiment. Hydrochloric acid was used to extract the Pb(II) from the adsorbents for 30 min in a constant temperature vibration shaker. After separation by centrifugation, the g-polyacrylamide/vermiculite was reused. Figure 16 reveals the Pb(II) adsorption capacity by g-polyacrylamide/vermiculite, and the removal efficiency of the regenerated g-polyacrylamide/vermiculite could obtain 90% at the fifth test cycle, which suggests that g-polyacrylamide/vermiculite adsorbents are promising for the efficient adsorption for Pb(II) (Gu et al. 2018).

Summary

An effective approach to functionalization of Verm for removal of Pb(II) was developed by significantly improving specific surface area and silanol groups of Verm by acid activation and further modifying Verm surface with a series of organic reactions for introducing more functional amine groups. The amine-functionalized Verm showed much greater efficiency in Pb(II) adsorption at different pH values than unmodified Verm. Furthermore, g-polyacrylamide/vermiculite has better selectivity for Pb(II) ion in comparison with Zn(II), Cd(II) and Cu(II) ions. The adsorption equilibrium data on g-polyacrylamide/vermiculite were in good agreement with the Langmuir adsorption isotherms. The kinetics data fit the pseudo-second-order kinetic well. The great adsorption capacity of g-polyacrylamide/vermiculite might be because of the presence of strong covalent bonds between Pb(II) and the –NH2 groups.

Heavy metal removal by 2:1 type layer-chain clay

Synthesis and properties of modified attapulgite

Preparation of chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/attapulgite nanocomposite

The preparation of chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/attapulgite was similar to that of chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/attapulgite: raw materials cross-linking using attapulgite, poly(vinyl alcohol) and chitosan; strong agitating the mixture (attapulgite, poly(vinyl alcohol) and chitosan) to get a homogeneous suspension for a desired duration time; the addition of a proper amount of glutaraldehyde solution to get a gel. After a number of freeze-thawed cycles, the chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/attapulgite nanocomposites were obtained. Furthermore, chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol) (without attapulgite) was also synthesized for comparison following the same steps.

Characterization of chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/attapulgite nanocomposites

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of attapulgite, poly(vinyl alcohol), chitosan and the chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/attapulgite adsorbent are shown in Fig. 17. The typical diffraction peak of attapulgite at 8.38° appeared corresponding to the interlayer spacing of 10.54 Å. After the interaction with poly(vinyl alcohol) and chitosan, the peak shifted to 8.34°, which corresponded to an interlayer spacing of 10.59 Å. The slight change suggests the formation of a weak interaction between attapulgite and poly(vinyl alcohol) or chitosan in the preparation process of chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/attapulgite, which resulted in the slight change in the microstructure of attapulgite crystal (Zhang et al. 2005; Xue et al. 2011).

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/attapulgite (CTS-PVA/APT) nanocomposite, poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA), chitosan (CTS) and attapulgite (APT), the changes of diffraction peaks suggest the formation of a weak interaction between attapulgite and poly(vinyl alcohol) or chitosan in the preparation process of chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/attapulgite, which resulted in the slight change in the microstructure of attapulgite crystal (Wang and Wang 2016)

Figure 18 shows the FTIR spectra of chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/attapulgite nanocomposite, chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol) and APT. In the spectrum of the chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/attapulgite, the broad peak at 3425 cm−1 was ascribed to the stretching vibrations of –NH2 and –OH groups. The absorption peak at 1650 cm−1 was ascribed to the C–O stretching vibration of –NHCOCH3 group, and the peak of the C–N bond, constituted through the reaction between –CHO groups of glutaraldehyde and –NH2 groups of chitosan, was also observed in this region. The absorption peaks in the 1030–1160 cm−1 region were assigned to the overlap of the stretching C–O and C–N, coupled with the bending of –OH groups. And the absorption peaks at 1421 and 1380 cm−1 were attributed to the bending and scissoring vibrations of –CH2 groups (Orozco-Guareño et al. 2010). In comparison with APT, in the spectrum of chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/attapulgite, the stretching vibration peaks of Si–OH at 3553 cm−1, 3583 cm−1 and 3617 cm−1 decreased and transferred to the lower wavenumbers (Blanco et al. 1989). The Si-OH stretching vibration and bending vibration of APT at 1660 cm−1, 1030 cm−1 and 984 cm−1 were not observed. Moreover, the bending vibration of Si–O at 507 cm−1 and 479 cm−1 shifted to lower wavenumber (464 cm−1). This indicates that the Si–OH groups on the surface of APT participated in the structure of the nanocomposites. The stretching vibration of –C–O–C– groups in the chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/attapulgite apparently shifted from 1073 cm−1 to the a lower wavenumber (1044 cm−1), in comparison with chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol). This was ascribed to the hydrogen bonds originating from –OH in the chitosan polymer and Si–OH on the surface of APT.

FTIR spectra of chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/attapulgite (CTS-PVA/APT) nanocomposite, chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol) (CTS-PVA) and attapulgite (APT), the changes of peak confirm that the designated chitosan and poly(vinyl alcohol) have successfully modified the structure of attapulgite (Wang and Wang 2016)

Cu(II) adsorption mechanisms on the chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/attapulgite

The binding energies and the X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) spectra of Cu-2p of chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/attapulgite before and after Cu(II) adsorption under different pH values are summarized in Table 9 and Fig. 19. There were no Cu-2p characteristic peaks in the spectrum of chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/attapulgite before and after Cu(II) adsorption under pH 2.0, which suggests that there were no Cu(II) ions adsorbing on the surfaces of chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/attapulgite under pH 2.0. After the adsorption test under pH 6.5, 5.0 and 3.0, the Cu-2p characteristic peaks of the samples appeared gradually; at the same time, the intensity of the above peaks increased with the increase in solution pH. Therefore, under these solution conditions, Cu(II) ions were adsorbed on the surfaces of chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/attapulgite, and the Cu(II) ions adsorption capacity increased with the increase in solution pH. Table 10 and Fig. 19 also summarize and show N-1s, C-1s and O-1s XPS spectra of the chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/attapulgite adsorbent before and after Cu(II) adsorption. This data were compiled in order to determine which functional groups are responsible for Cu(II) adsorption. The results indicate that groups with carbon atoms did not take part in the Cu(II) adsorption process.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) spectra of C-1s, O-1s, N-1s and Cu-2p of chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/attapulgite before and after the adsorption of Cu(II) under different pH conditions, Cu(II) ions were adsorbed on the surfaces of chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/attapulgite, and the Cu(II) ions adsorption capacity increased with the increase in solution pH (Wang and Wang 2016)

Summary

A novel chitosan-poly(vinyl alcohol)/attapulgite nanocomposite adsorbent used for the removal of Cu(II) ions from aqueous solutions was prepared via a glutaraldehyde cross-linking method in combination with an alternate freeze-thawed process. This nanocomposite shows superior performance in the treatment of wastewater containing low-concentration Cu(II) ions. The adsorption capacity and mechanism of the nanocomposite for Cu(II) ions are greatly influenced by the pH value of solutions. The whole adsorption process fits the pseudo-second-order kinetic model better, though the adsorption process in the initial 7 min fits well with the pseudo-first-order kinetic equation. The adsorption process of Cu(II) ions on the nanocomposite is endothermic and can be better explained by the Freundlich model than by the Langmuir model.

For the sake of comparison and to describe the approximate comparative studies on the adsorptive performance of various clay adsorbent materials with each other, Table 11 shows the maximum adsorption capacities, synthesis method and adsorption mechanism of clay minerals.

Conclusion

Clay minerals have been used as good adsorbents attributed to the existence of different types of active sites located at the surfaces, such as ion-exchange sites, Lewis acid sites and Bronsted sites. Both modified natural clays and synthetic clays, such as halloysite, bentonite, montmorillonite, vermiculite and attapulgite, have been the most extensively used clays for preparing nanocomposites with high performance. This review introduced clay-based adsorbents in detail for the removal of heavy metals from aqueous media, and different mechanisms of the corresponding adsorption processes were discussed. In general, (1) the heavy metal adsorption capacities of several clay composites is much higher than those of natural clays; (2) various characterization measurements were combined to analyze the adsorption mechanisms, including the Hg(II) ions adsorption selectivity; (3) pseudo-second-order kinetic models fit well with the experimental data in most studies; and (4) heavy metal adsorption by various clay composite adsorbents fit the Langmuir isotherm models well. Also, factors including temperature, contact time, pH and initial solution concentration can obviously affect the adsorption process. The present work contributes to the development of novel cost-efficient adsorbents with great adsorption capacities and unique selectivity for different heavy metals. In addition, this study promotes new, efficient methods for the removal of heavy metal ions from aqueous media.

For the future, low-cost adsorbents, such as natural and modified clays, show great promise. The applications of natural and modified clays in commercial wastewater treatment are expected to be significant. Future efforts will involve large-scale application of natural and modified clays, which will require significant financial and technological resources. Modified clays in combination with other fillers would be a subject of several future investigations for which the work has been started. The goals for their use are vast, and hence, there can be many pathways for utilization of these clays. In terms of chemistry of modification of clays, although a few have been attempted, there are opportunities for new chemistries and exploitation of these modified clays. Furthermore, advanced efforts to develop analytical methods for the determination of more accurate, convenient, and reliable quantitative mineral analysis are likely to be made. Further modification and design of nanoclays, metal oxide delaminated and pillared clays, chemically treated clay mineral surfaces, and composite clay structures will provide potential future applications in water remediation.

References

Ahmaruzzaman M (2011) Industrial wastes as low-cost potential adsorbents for the treatment of wastewater laden with heavy metals. Adv Colloid Interface Sci 166(1):36–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cis.2011.04.005

Ajmal M, Rao RAK, Ahmad R, Ahmad J, Rao LAK (2001) Removal and recovery of heavy metals from electroplating wastewater by using Kyanite as an adsorbent. J Hazard Mater 87(1–3):127–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-3894(01)00234-5

Anadao P, Hildebrando EA, Pajolli ILR, Pereira KRD, Wiebeck H, Diaz FRV (2011) Montmorillonite/carbon nanocomposites prepared from sucrose for catalytic applications. Appl Clay Sci 53(2):288–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clay.2011.04.022

Bakandritsos A, Steriotis T, Petridis D (2004) High surface area montmorillonite-carbon composites and derived carbons. Chem Mater 16(8):1551–1559. https://doi.org/10.1021/cm0350030

Bandeira LC, Calefi PS, Ciuffi KJ, de Faria EH, Nassar EJ, Vicente MA, Trujillano R (2012) Preparation of composites of laponite with alginate and alginic acid polysaccharides. Polym Int 61(7):1170–1176. https://doi.org/10.1002/pi.4196

Baydemir G, Andac M, Bereli N, Say R, Denizli A (2007) Selective removal of bilirubin from human plasma with bilirubin-imprinted particles. Ind Eng Chem Res 46(9):2843–2852. https://doi.org/10.1021/ie0611249

Bedoui K, Bekri-Abbes I, Srasra E (2008) Removal of cadmium(II) from aqueous solution using pure smectite and Lewatite S 100: the effect of time and metal concentration. Desalination 223(1):269–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2007.02.078

Bhattacharyya KG, Gupta SS (2008) Adsorption of a few heavy metals on natural and modified kaolinite and montmorillonite: a review. Adv Colloid Interface Sci 140(2):114–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cis.2007.12.008

Blanco C, González F, Pesquera C, Benito I, Mendioroz S, Pajares JA (1989) Differences between one aluminic palygorskite and another magnesic by infrared spectroscopy. Spectrosc Lett 22(6):659–673. https://doi.org/10.1080/00387018908053926

Bosco SMD, Jimenez RS, Vignado C, Fontana J, Geraldo B, Figueiredo FCA, Mandelli D, Carvalho WA (2006) Removal of Mn(II) and Cd(II) from wastewaters by natural and modified clays. Adsorption 12(2):133–146. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10450-006-0375-1

Bradl HB (2004) Adsorption of heavy metal ions on soils and soils constituents. J Colloid Interface Sci 277(1):1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2004.04.005

Brindley GW, Robinson K (1945) Structure of Kaolinite. Nature 156(3970):661–662. https://doi.org/10.1038/156661b0

Cao J, Cao H, Zhu Y, Wang S, Qian D, Chen G, Sun M, Huang W (2016) Rapid and effective removal of Cu2+ from aqueous solution using novel chitosan and laponite-based nanocomposite as adsorbent. Polymers 9(12):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym9010005

Catalano JG, Brown GE (2005) Uranyl adsorption onto montmorillonite: evaluation of binding sites and carbonate complexation. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 69(12):2995–3005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2005.01.025

Chakraborty A, Deva D, Sharma A, Verma N (2011) Adsorbents based on carbon microfibers and carbon nanofibers for the removal of phenol and lead from water. J Colloid Interface Sci 359(1):228–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2011.03.057

Chen GH (2004) Electrochemical technologies in wastewater treatment. Sep Purif Technol 38(1):11–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2003.10.006

Chen J, Blume HP, Beyer L (2000) Weathering of rocks induced by lichen colonization: a review. Catena 39(2):121–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0341-8162(99)00085-5

Chen YY, Wang J, Shi GT, Sun XJ, Chen ZL, Xu SY (2011) Human health risk assessment of lead pollution in atmospheric deposition in Baoshan District, Shanghai. Environ Geochem Health 33(6):515–523. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10653-010-9368-9

Chen WF, Zhu DQ, Zheng SR, Chen W (2014) Catalytic effects of functionalized carbon nanotubes on dehydrochlorination of 1,1,2,2-tetrachloroethane. Environ Sci Technol 48(7):3856–3863. https://doi.org/10.1021/es405683d

Choudhury A, Kennedy IR (2005) Nitrogen fertilizer losses from rice soils and control of environmental pollution problems. Commun Soil Sci Plant Anal 36(11–12):1625–1639. https://doi.org/10.1081/css-200059104

Darder M, Colilla M, Ruiz-Hitzky E (2005) Chitosan–clay nanocomposites: application as electrochemical sensors. Appl Clay Sci 28(1):199–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clay.2004.02.009

de Lapparent J (1936) Formula and schematic structure of attapulgite. C R Hebd Seances Acad Sci 202:1728–1731

de Paiva LB, Morales AR, Diaz FRV (2008) Organoclays: properties, preparation and applications. Appl Clay Sci 42(1–2):8–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clay.2008.02.006

Demir-Cakan R, Baccile N, Antonietti M, Titirici MM (2009) Carboxylate-rich carbonaceous materials via one-step hydrothermal carbonization of glucose in the presence of acrylic acid. Chem Mater 21(3):484–490. https://doi.org/10.1021/cm802141h

Deng YJ, Dixon JB, White GN (2006) Bonding mechanisms and conformation of poly(ethylene oxide)-based surfactants in interlayer of smectite. Colloid Polym Sci 284(4):347–356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00396-005-1388-0

Dhal B, Thatoi HN, Das NN, Pandey BD (2013) Chemical and microbial remediation of hexavalent chromium from contaminated soil and mining/metallurgical solid waste: a review. J Hazard Mater 250:272–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2013.01.048

Du ML, Guo BC, Jia DM (2010) Newly emerging applications of halloysite nanotubes: a review. Polym Int 59(5):574–582. https://doi.org/10.1002/pi.2754

Duman O, Tunç S (2009) Electrokinetic and rheological properties of Na-bentonite in some electrolyte solutions. Microporous Mesoporous Mater 117(1):331–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micromeso.2008.07.007

Duquesne E, Moins S, Alexandre M, Dubois P (2007) How can nanohybrids enhance polyester/sepiolite nanocomposite properties? Macromol Chem Phys 208:2542

Elom NI, Entwistle J, Dean JR (2014) Human health risk from Pb in urban street dust in northern UK cities. Environ Chem Lett 12(1):209–218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-013-0436-0

El-Sherbiny S, Morsy FA, Hassan MS, Mohamed HF (2015) Enhancing Egyptian kaolinite via calcination and dealumination for application in paper coating. J Coat Technol Res 12(4):739–749. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11998-015-9672-5

Erdem E, Karapinar N, Donat R (2004) The removal of heavy metal cations by natural zeolites. J Colloid Interface Sci 280(2):309–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2004.08.028

Feng XB, Qiu GL (2008) Mercury pollution in Guizhou, Southwestern China: an overview. Sci Total Environ 400(1–3):227–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.05.040

Feng M, Wang Z, Dionysiou DD, Sharma VK (2018a) Metal-mediated oxidation of fluoroquinolone antibiotics in water: a review on kinetics, transformation products, and toxicity assessment. J Hazard Mater 344:1136–1154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2017.08.067

Feng M, Zhang P, Zhou HC, Sharma VK (2018b) Water-stable metal-organic frameworks for aqueous removal of heavy metals and radionuclides: a review. Chemosphere 209:783–800. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.06.114

Frenkel M (1974) Surface acidity of montmorillonites. Clays Clay Miner 22(5–6):435–441. https://doi.org/10.1346/ccmn.1974.0220510

Fu FL, Wang Q (2011) Removal of heavy metal ions from wastewaters: a review. J Environ Manage 92(3):407–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2010.11.011

Galan E (1996) Properties and applications of palygorskite-sepiolite clays. Clay Miner 31(4):443–453. https://doi.org/10.1180/claymin.1996.031.4.01

Gale JD, Cheetham AK, Jackson RA, Catlow CRA, Thomas JM (1990) Computing the structure of pillared clays. Adv Mater 2(10):487–490. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.19900021010

Gao ZM, Bandosz TJ, Zhao ZB, Han M, Qiu JS (2009) Investigation of factors affecting adsorption of transition metals on oxidized carbon nanotubes. J Hazard Mater 167(1–3):357–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.01.050

Gomes PC, Fontes MPF, da Silva AG, Mendonca ED, Netto AR (2001) Selectivity sequence and competitive adsorption of heavy metals by Brazilian soils. Soil Sci Soc Am J 65(4):1115–1121. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj2001.6541115x

Gruner JW (1932) The crystal structure of Kaolinite. ZKri 83(1/2):75–88

Gu S, Wang L, Mao X, Yang L, Wang C (2018) Selective adsorption of Pb(II) from aqueous solution by triethylenetetramine-grafted polyacrylamide/vermiculite. Materials. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma11040514

Guangyan T, Yuru K, Bin M, Aiqin W (2014) Attapulgite modified with silane coupling agent for phosphorus adsorption and deep bleaching of refined palm oil. Adsorpt Sci Technol 32(1):37–48. https://doi.org/10.1260/0263-6174.32.1.37

He MC, Wang XQ, Wu FC, Fu ZY (2012) Antimony pollution in China. Sci Total Environ 421:41–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.06.009

Hendricks SB (1942) Lattice structure of clay minerals and some properties of clays. JG 50(3):276–290. https://doi.org/10.1086/625051

Hendricks SB, Jefferson ME (1938) Crystal structure of vermiculites and mixed vermiculite-chlorites. Am Miner 23(12):851–862

Ho YS, McKay G (1999) Pseudo-second order model for sorption processes. Process Biochem 34(5):451–465. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0032-9592(98)00112-5

Hong H, Jiang W-T, Zhang X, Tie L, Li Z (2008) Adsorption of Cr(VI) on STAC-modified rectorite. Appl Clay Sci 42(1):292–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clay.2008.01.015

Huang X, Hou X, Song F, Zhao J, Zhang L (2016) Facet-dependent Cr(VI) adsorption of hematite nanocrystals. Environ Sci Technol 50(4):1964–1972. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.5b05111

Jakob A, Stucki S, Struis R (1996) Complete heavy metal removal from fly ash by heat treatment: influence of chlorides an evaporation rates. Environ Sci Technol 30(11):3275–3283. https://doi.org/10.1021/es960059z

Jean J, Perrodin Y, Pivot C, Trepo D, Perraud M, Droguet J, Tissot-Guerraz F, Locher F (2012) Identification and prioritization of bioaccumulable pharmaceutical substances discharged in hospital effluents. J Environ Manage 103:113–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2012.03.005

Jiang M-Q, Jin X-Y, Lu X-Q, Chen Z-L (2010) Adsorption of Pb(II), Cd(II), Ni(II) and Cu(II) onto natural kaolinite clay. Desalination 252(1):33–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2009.11.005

Kadirvelu K, Faur-Brasquet C, Le Cloirec P (2000) Removal of Cu(II), Pb(II), and Ni(II) by adsorption onto activated carbon cloths. Langmuir 16(22):8404–8409. https://doi.org/10.1021/la0004810

Kapoor A, Viraraghavan T (1995) Fungal biosorption: an alternative treatment option for heavy metal bearing wastewaters—a review. Bioresour Technol 53(3):195–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/0960-8524(95)00072-1

Karimi L, Salem A (2011) The role of bentonite particle size distribution on kinetic of cation exchange capacity. J Ind Eng Chem 17(1):90–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiec.2010.12.002

Kasgoz H, Durmus A, Kasgoz A (2008) Enhanced swelling and adsorption properties of AAm-AMPSNa/clay hydrogel nanocomposites for heavy metal ion removal. Polym Adv Technol 19(3):213–220. https://doi.org/10.1002/pat.999

Keng PS, Lee SL, Ha ST, Hung YT, Ong ST (2014) Removal of hazardous heavy metals from aqueous environment by low-cost adsorption materials. Environ Chem Lett 12(1):15–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-013-0427-1

Kiani G (2014) High removal capacity of silver ions from aqueous solution onto Halloysite nanotubes. Appl Clay Sci 90:159–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clay.2014.01.010