Abstract

Internationally active firms rely intensively on trade credits even though they are considered particularly expensive. This phenomenon has been little explored so far. Our analysis focusses on cash-in-advance financing. With the help of a theoretical model, we show that firms intensively use cash-in-advance because it serves as a quality signal that reduces the high uncertainty related to international transactions. Specifically, cash-in-advance provided from a foreign buyer to an exporter can alleviate adverse selection and the risk of moral hazard. Thus, exporting becomes more profitable which allows less productive firms to start exporting. We use unique survey data on German enterprises from the Business Environment and Enterprise Performance Survey to test the effect of cash-in-advance financing on firms’ exporting participation. Accounting for endogeneity, we find that cash-in-advance has a positive impact on the firms’ probability to export. Moreover, our results suggest that this effect is particularly strong for less productive firms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Aggravated trade finance conditions have been suggested as one of the reasons why trade flows collapsed in the wake of the 20080–2009 financial crisis.Footnote 1 Indeed, a great part of all trade transactions are supported by some form of trade finance (Auboin 2009). Surprisingly, though, the main part of trade finance takes the form of inter-firm credits, also called trade credits: according to a survey by the IMF, about 60 % of all trade transactions are financed via trade credits (IMF 2009). Trade credits are extended bilaterally between firms and exist in the form of supplier credits and cash-in-advance. Cash-in-advance (CIA) refers to payments made in advance by the buyer of a good to the seller. In contrast, a supplier credit is granted from the seller of a good to the buyer such that the payment of the purchasing price can be delayed for a certain period of time.Footnote 2 The intensive use of trade credits is surprising since they are considered a particularly expensive form of financing: implicit annual trade credit interest rates can amount to up to 40 % (Petersen and Rajan 1997). Why trade credits are so prevalent in international trade, despite their high cost, has been little studied so far.

This paper aims at closing this gap. We argue that international transactions are inherently subject to more uncertainty than domestic transactions and that trade credits serve as a quality signal that helps reduce this high uncertainty. In our analysis, we focus on CIA financing and provide a rationale for the use of expensive trade credits to finance international trade. For this purpose, we develop a model of internationally active firms that need outside finance to be able to export. In our model, asymmetric information problems deter less productive firms from exporting if only bank financing is available. Access to CIA reduces the asymmetric information problem and thus promotes the export participation of firms that are not able to export with traditional bank financing. We test our prediction with data from the Business Environment and Enterprise Performance Surveys (BEEPS) for German firms in 2004. This dataset is ideal for our purposes since it contains data on the use of CIA and the export activity of firms. Accounting for endogeneity, we find that firms that receive CIA from their trading partners have on average a 25 % higher probability to export than firms that do not receive CIA financing. Likewise, a 1 % increase in CIA financing increases the export probability of firms on average by 15 %. We find that the export fostering effect of CIA is particularly strong for less productive firms and firms that experience difficulties in accessing bank finance.

Our analysis is the first to explicitly analyze the effects of CIA financing on the export participation of firms. In our model, we show that the productivity threshold to profitably export is lower if a firm is provided with CIA by its foreign trading partner. Using survey data, we can provide direct evidence of the beneficial effects of CIA financing on exporting. In the survey, firms report how much of their sales are paid in advance by customers. Thus, we need not rely on proxies for CIA availability such as trade accounts receivable from balance sheet data. Since the use of CIA by firms is very likely related to unobserved firm characteristics we apply an instrumental variable approach. Accounting for endogeneity, we find that CIA availability strongly fosters the export participation of firms. In addition, we analyze the differential impact of CIA financing on exporting for less productive firms and firms that experience difficulties in accessing bank finance. We find that these firms more strongly benefit from CIA financing in terms of their export participation which supports the signalling function of CIA.

Our analysis is related to two different strands of literature. First, it builds on the literature on trade credits. In Lee and Stowe (1993), firms extend a trade credit to signal product quality to their (domestic) customers. Another paper on the warranty by quality hypothesis was simultaneously developed by Long et al. (1993). In a more recent paper, Klapper et al. (2012) provide empirical evidence on the quality signalling motive for a small sample of US and European firms. They find that less trustworthy suppliers offer longer payment periods to their buyers. Moreover, suppliers offer prepayment discounts to less trustworthy buyers in order to minimize payment risk. This signalling motive should hold a fortiori for international transactions that suffer from an even higher degree of uncertainty. As we show in our model, even though trade credits are intrinsically more costly than bank credits, this disadvantage is more than compensated for by the reduction of uncertainty, so less productive firms benefit from access to trade credits. Biais and Gollier (1997) develop a model where the firm that extends the trade credit signals its belief in the creditworthiness of the firm it provides with trade credit. Their argument requires that the trade partner has an information advantage relative to the bank. Giannetti et al. (2011), however, find that trading partners have no persistent informational advantage. Burkart and Ellingsen (2004) derive that trade credit financing can improve access to bank credit financing for firms. Their main argument is that trade credits are less prone to diversion than cash. This implies that firms that receive trade credits are less likely to commit moral hazard and banks are more willing to lend additional credit to these firms.Footnote 3 We, in contrast, assume that the firm extending CIA signals its own quality, which seems to be a more natural and realistic assumption. Moreover, we explicitly consider international transactions which are inherently prone to aggravated information asymmetries and differ in the choice of the financing mode from domestic transactions. Our model shows how trade credits can alleviate asymmetric information problems with regard to foreign trading partners and thus promote trade.

Furthermore, the trade credit literature mainly focusses on the use of supplier credits. The only exception is Mateut (2012) who investigates the determinants of CIA financing by French firms. We examine the effect that CIA financing has on the export participation of firms. This is especially interesting for two reasons. First, prepayment financing is also intensively used by firms and thus provides a relevant alternative to supplier credit financing.Footnote 4 Second, CIA should have a stronger signalling function than supplier credits. The reason is that a supplier credit can be extorted by simply overstretching the payment period. In contrast, CIA needs to be actively given by the trading partner.

Second, we relate to the literature on trade credit financing in international trade. Only recently has the literature on trade credits taken international transactions into its focus, investigating the optimal choice of trade credit. In Schmidt-Eisenlohr (2013), financial market characteristics and the contractual environment of both the foreign and domestic market influence the choice of trade credit by firms. Hoefele et al. (2013) test these predictions and find empirical support that financing costs and the strength of contract enforcement determine the choice of trade credit contracts for international transactions. Similarly, Antràs and Foley (2011) study how a firm’s choice of using CIA versus supplier credit depends on the extent of contractual frictions in the foreign trading partner’s country. The authors confirm their predictions using data from a large US exporting firm. Ahn (2011) investigates which side of the transaction should provide a trade credit and finds that it should be the trade partner that possesses the larger amount of collateral. Furthermore, he provides an explanation for how a lack of trade finance could have contributed to the drop in global trade during the financial crisis. Using Berne Union data on export credit insurance, Auboin and Engemann (2014) analyse the effect of trade credit on trade on a macro level through a whole cycle. They find a positive effect of export credit insurance, as a proxy for trade credits, on trade, not varying between crisis and non-crisis periods. Olsen (2011) focuses on the role of banks in international trade. He shows that by issuing letters of credit, banks can help to overcome enforcement problems between exporters and importers. Glady and Potin (2011) provide empirical evidence on the importance of letters of credit when country default risk is high. While the focus of these papers is primarily on the choice of the trade credit form as a function of the level of uncertainty, we focus instead on the rationale for using CIA as an alternative or as a complement to cheaper bank financing. We show how CIA solves both a moral hazard and an adverse selection problem for an exporter. Hence, we find that CIA fosters international trade.Footnote 5

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: In Sect. 2, we develop a model for an exporter receiving CIA. Section 3 introduces the dataset and provides summary statistics. In Sect. 4, we set out the empirical strategy to test our model predictions and present our results. Section 5 concludes.

2 Theoretical framework

Consider a two-period economy, \({\{t=0,1\}} \), in which a firm considers whether to produce for the foreign market.Footnote 6 When producing the quantity x in \(t=0\), a firm faces the convex cost function \(k=\frac{x^2}{2(1+\beta )}\). \((1+\beta )\) denotes the productivity level of the firm so that more productive firms produce at lower variable costs, \(\beta > 0\).Footnote 7 Following the current literature, we characterize a firm by its productivity level which determines its decision to become internationally active (see Melitz 2003). Additionally, the firm has to incur a fixed cost \(F_{Ex}\) associated with foreign market entry, e.g., costs related to the establishment of a distribution network or market research in the foreign market. At the end of \(t=0\), the firm sells its good at price p in the foreign market to an importing firm. In \(t=1\), the importing firm can resell the good to final customers on the regular market at the exogenous market price \(\hat{p}\) and generate revenue.

We assume that the exporting firm does not possess any internal funds and has to finance all costs of production externally in \(t=0\), before any revenues are generated. The importing firm does not possess any cash, either, to pay for the exporter’s good. There are two possibilities of how payment by the importer to the exporter can occur: either after delivery in \(t=1\), as soon as the importer has generated own revenues, or upfront before the exporter starts to produce. In the former scenario, the exporter has to finance all production costs via a bank credit which is equivalent to extending a supplier credit to the importer. In the latter scenario, the importer has to access external finance to be able to pay in advance.

When payment occurs after delivery, the exporter faces two sources of uncertainty. The first one is an adverse selection problem with regard to the importer’s type. With probability \(\mu\), \(0<\mu<1\), the importer is of high quality (H) and so is able to successfully market the exporter’s good on the regular market. With probability \((1-\mu )\) the importer is of low quality (L) which means that positive revenues cannot be generated and hence the exporter is not paid.

Second, a moral hazard problem can occur, due to the long distances in international trade and difficulties of tracing the importer’s behavior. Instead of selling the good on the regular market, the importer can divert the good and derive a private payoff of \(\phi x\), blaming adverse market conditions for not generating positive revenues. To fix ideas, we assume that the market demand for the exporter’s good on the regular foreign market is uncertain: demand in the foreign market is positive with probability \(\lambda \), \(0<\lambda <1,\) and it is zero with probability \((1-\lambda )\). No revenues are generated in the latter case and the importer cannot repay the exporter, even if he is of high quality. We assume that diverting the good is inefficient, i.e., \(0<\phi <\lambda \hat{p}\). Whether or not the high-quality importer diverts the good depends on the price he is supposed to pay to the exporter in case of successfully marketing the good. The low-quality importer always diverts the good since he cannot successfully market it.Footnote 8 Hence, positive export revenues are generated only if the importer is of high quality, market demand is positive, and the high-quality importer does not divert the good.Footnote 9

The timing of the game is as follows:

-

1.

Nature determines the importer’s quality where \(Prob(H)=\mu \) and \(Prob(L)=\left( 1-\mu \right) \). The importer learns its type.

-

2.

In \(t=0\), the exporting firm specifies a price p for the good to be exported and decides on its financing mode, whether to use pure bank credit, pure CIA or partial CIA and bank credit. When being asked for CIA, the importer decides whether to extend the fraction \(\alpha \) in advance or not, where \(0\le \alpha \le 1\), depending on the importer’s type.

-

3.

The bank observes whether or not a CIA payment by the importer in \(t=0\) took place and decides on the extension of bank credit.

-

4.

After observing the decisions made by the importer and the bank, the firm decides whether to produce and export or not.

-

5.

In \(t=1\), payoffs are realized.

We do not consider payment at delivery (at the end of \(t=0\)) because this implies that both trading partners have to use costly external finance instead of only one of the partners. One could argue that in this case, both trading partners have to use external finance for only half of the time and thus it is not clear whether payment at delivery is strictly dominated by either supplier credit or CIA. However, in contrast to partial CIA and bank credit financing the uncertainty with regard to the importer’s quality is not reduced for the exporter at the time when the costs of production are incurred (at the beginning of \(t=0\)). Therefore, payment at delivery appears to be more costly than the two alternatives we consider.Footnote 10

2.1 Pure bank credit financing

In the following, we consider the case in which payment occurs after delivery and the exporter has to apply for a bank credit to finance all costs of production. The bank credit can be repaid only if the importer pays for the goods as agreed on. This depends on the type of the importer, the demand in the regular foreign market, and the decision whether to divert or resell the good. The exporter maximizes his profits with regard to the quantity x and price p

subject to

and

The exporter receives expected revenues of \(\lambda \mu px\) and finances the total costs of production via a bank credit. The exporter repays the amount borrowed only in case of positive revenues (\(\lambda \mu \)) and is charged a gross interest rate \((1+r_B)\) by the bank. The first condition (1.1) is the bank’s participation constraint. Banks operate under perfect competition and make zero profits. The bank faces the same uncertainty as the exporter concerning the quality type of the importer and the market risk, so credit repayment by the exporter is uncertain. For the focus of our study, we assume that there is no asymmetric information with regard to the exporter’s quality and the exporter is eligible for advance payment from the importer’s point of view.Footnote 11 The bank’s expected revenues have to be equal to the refinancing costs of the bank where \((1+\bar{r}_B)\) refers to the gross refinancing interest rate of the bank. The collateral in case of non-repayment is normalized to 0. For the bank to break even, it is necessary that \((1+r_B)=\frac{(1+\bar{r}_B)}{\lambda \mu }\). The higher the certainty about the foreign market demand and the importer quality, the lower the interest rate the bank demands. In the case of complete certainty, \(\lambda =\mu =1\), the bank demands exactly its gross refinancing rate.

Conditions (1.2a) and (1.2b) describe the participation constraints of the high- and the low-quality importer, respectively. Conditions (1.3a) and (1.3b) state the incentive compatibility constraints of the high- and the low-quality importer. To prevent problems related to moral hazard, for each unit of x sold to the high-quality importer, the exporting firm demands a price p such that the high-quality importer’s expected revenues from selling the good and repaying the exporter in case of positive market demand must be at least as high as the gain from diversion (1.3a). We assume that the exporter has full market power in setting the price for the good, so p is given by \(p=\hat{p}-\frac{\phi }{\lambda }\). Our assumption on the distribution of the bargaining power implies that the expected profit of the exporter is maximized. It is straightforward to extend our analysis to cases when this assumption is relaxed. Assuming that the importer has some, but less than full, market power changes our results only quantitatively but not qualitatively. For the low quality importer, we expect it to divert the good which is trivially fulfilled with (1.3b). It cannot mimic the high-quality importer and sell the good on the regular market which means it cannot pay for the good either.

Maximizing the exporter’s profit function with regard to x, we can derive the optimal quantity exported with pure bank credit financing:

Plugging (2) into the exporter’s profit function and setting it equal to zero yields the minimum productivity level required to make at least zero profits:

Firms with a productivity level \((1+\beta )<\left( 1+\beta \right) _{Ex}^{BC}\) will not be able to export since at this level of uncertainty, they are unable to break even.Footnote 12 We refer to these firms as productivity constrained implying that they are not productive enough to export with pure bank financing.

In our model, the productivity threshold is lower the lower the uncertainty with regard to the type of the foreign customer (higher \(\mu \)) and positive market demand (higher \(\lambda \)). In a domestic transaction, where information asymmetries are less severe, i.e., \(\lambda \) and \(\mu \) are close to 1, the productivity cut-off would be distinctly lower. The threshold also decreases with lower refinancing costs incurred by the bank and increases with higher fixed costs of exporting. Firms that can charge a higher price \(p\), e.g., if the moral hazard problem is less severe (lower \(\phi \)), can be relatively less productive to start exporting since their expected revenues are higher.

2.2 Pure CIA financing

Next, we consider payment before delivery. If the exporter can enforce advance payment of the total invoice before production takes place in \(t=0\), moral hazard and adverse selection can be eliminated completely. Low-quality importers cannot afford to pay in advance and thus reveal their type by not agreeing to full advance payment. Moreover, if the exporter receives the payment before he starts producing, problems related to moral hazard are irrelevant from the exporter’s point of view. Note also that an additional bank credit is not needed as the total costs of production can be paid out of the revenues received up-front.

When paying the invoiced amount in advance, the importer faces refinancing costs of \((1+\bar{r}_{Im})\). We assume that the importer faces a higher refinancing rate than the bank, \(\bar{r}_{Im}>\bar{r}_{B}\). The higher refinancing rate reflects risk and asymmetric information issues that the importer has to cover. In addition, the importer is not specialized in providing credits as a bank is, and hence may have higher costs of dealing with these financial aspects. We can interpret \(\bar{r}_{Im}\) as a measure of the financial constraint of the importer, i.e., the higher is \(\bar{r}_{Im}\), the less able is the importer to provide CIA. Alternatively, \(\bar{r}_{Im}\) can be seen as the importer’s opportunity costs. The exporter maximizes the following profit function with pure CIA financing

subject to

Recall our assumption that the exporter has full bargaining power. Hence, with pure CIA financing, the exporter demands a price \(\tilde{p}\) such that the high-quality importer just breaks even, (4.1a): \(\tilde{p}= \left( \frac{\lambda \hat{p}}{1+\bar{r}_{Im}}\right) \). (4.1b) ensures that the low-quality importer has no incentive to pay the full amount in advance since his gain from diversion does not cover the costs. In combination with condition (4.1a), this also implies that diversion is inefficient \((\lambda \hat{p}x\ge \phi x)\).

This leads to the following minimum productivity level

Comparing the minimum productivity level required for pure CIA financing to the one for pure bank credit financing, we find that pure CIA financing requires a higher minimum productivity level if

The above condition is fulfilled if the refinancing costs of the importer are high relative to the refinancing costs of the bank. If \(\bar{r}_{Im}\) is high, firms that cannot export in the case of pure bank credit financing still cannot with pure CIA financing, either. This is due to the fact that the higher the refinancing costs, the lower the price \(\tilde{p}\) exporters can demand for their goods. In contrast, if the adverse selection problem is acute (low \(\mu \)), pure CIA financing is attractive for financially constrained firms because the elimination of the adverse selection problem is very valuable. To simplify our presentation, in the following we restrict attention to parameter cases where pure CIA is more expensive than pure bank credit financing, i.e., condition (6) is fulfilled. This seems to be the most relevant case since full pre-payments are very rare in practice.

2.3 Partial CIA and bank credit financing

Consider now a combination of bank credit and CIA financing where only a fraction \(\alpha \) of the invoice payment is made in advance. This enables the importing firm to save some of the high refinancing costs while it still allows the exporter to solve the adverse selection and the moral hazard problem. The payment made in advance is used to pay a part of the total production costs, the rest is financed via bank credit.

The fraction paid in advance can now serve as a signal of the importer’s quality type to the bank and the exporter. Three cases can occur after observing a certain \(\alpha \): first, if the bank believes that the importing firm is of high quality (\(Prob(H)=1\)) it will provide an additional bank credit at a lower interest rate to the exporting firm. Second, if the bank believes that the importer is of low quality (\(Prob(H)=0\)), it will not provide any bank credit at all because the exporter is not able to repay the bank when trading with a low-quality importer. Third, if the bank cannot infer the quality type from the amount paid in advance (\(Prob(H)=\mu \)), it will demand the same interest rate as in the case of pure bank credit financing.

We consider two types of equilibria in this game, separating and pooling equilibria. In a separating equilibrium, an informative signal is given, in a pooling equilibrium the signal sent by the importer is not informative. In the separating equilibrium, the exporter faces the following maximization problem

subject to

The exporter receives the share \(\alpha \) of his revenues in advance and obtains the rest with probability \(\lambda \) in case of positive market demand. He uses the advance payment to finance part of the total costs and applies for a bank credit for the rest of the total costs. Since the signal is informative, the bank requires the gross interest rate \(\left( \frac{1+\bar{r}_B}{\lambda }\right) \), condition (7.1). Conditions (7.2a) and (7.2b) describe the participation constraints of the high- and the low-quality importer when extending the share \(\alpha ^{H}\) and \(\alpha ^{L}\) of the purchasing price \(\check{p}x\) in advance. The terms in condition (7.2a) can be read as follows: the high-quality importer receives \(\hat{p}\) with probability \(\lambda \) from selling the good on the regular foreign market; it pays the share \(\alpha ^{H}\) of the purchasing price in advance, which it needs to refinance at \(\bar{r}_{Im}\); it pays the rest of the input with probability \(\lambda \), when it has successfully sold the good on the regular foreign market. Condition (7.2b) states that the low-quality importer pays the share \(\alpha ^L\) of the input good in advance but does not receive the good since the bank does not provide bank credit if the exporter trades with the low-quality type in the separating equilibrium. Conditions (7.3a) and (7.3b) are the incentive compatibility constraints of both importer types that make sure that the high quality importer does not mimic the low quality importer and vice versa. Condition (7.4) rules out moral hazard by the high-quality importer by guaranteeing that the high-quality importer prefers to sell the good on the regular market rather than diverting it. Note that we assume that the importer cannot be forced to pay the second installment if the good is diverted. However, if the importer sells the good on the regular market, this is observable and verifiable to the exporter, so that payment of the second installment can be enforced. It is easily verified that by choosing

all five conditions are fulfilled in such a way that the exporter’s payoff is maximized.

Proposition 1 describes the separating perfect Bayesian equilibrium that maximizes the exporter’s payoff. The first bracket contains the importers’ strategies, the second bracket states the strategies of the bank. The third part gives the equilibrium and off-equilibrium beliefs.

Proposition 1

There exists a separating perfect Bayesian equilibrium with

where \(\alpha ^{Sep}=\frac{\phi /(1+\bar{r}_{Im})}{\hat{p}+ \frac{\phi }{(1+\bar{r}_{Im})}- \frac{\phi }{\lambda }}\) and the price demanded for the exported good is \(\check{p}=\hat{p}-\frac{\phi }{\lambda }+\frac{\phi }{(1+\bar{r}_{Im})}\). In this separating equilibrium, the high-quality importer extends the share \(\alpha ^{H}=\alpha ^{Sep}\) in advance and the low-quality importer chooses not to extend CIA at all. When observing \(\alpha =\alpha ^{Sep}\), the bank updates its belief according to Bayes Rule such that \(Prob\left( H|\alpha =\alpha ^{Sep}\right) =1\) and extends additional bank credit at a lower interest rate, \(\left( \frac{1+\bar{r}_B}{\lambda }\right) \). When observing \(\alpha =0\), the bank’s belief is \(Prob\left( H|\alpha =0\right) =0\) and it denies additional bank credit.

Proof

For a proof of the existence of the separating equilibrium, see the Online Appendix.

In the separating equilibrium, the minimum productivity threshold for exporting \((1+\beta )_{Ex}^{Sep}\) equals:

Firms with a productivity level lower than \((1+\beta )_{Ex}^{Sep}\) cannot export since they have negative expected profits. As before, the productivity threshold increases with higher fixed costs and higher bank refinancing costs. It also increases with higher importer refinancing costs and a higher marginal benefit from diversion. In addition, we consider the following pooling equilibrium.

Proposition 2

There exists a pooling perfect Bayesian equilibrium with

where \(\alpha ^{Pool}=\frac{\phi /(1+\bar{r}_{Im})}{\hat{p}+ \frac{\phi }{(1+\bar{r}_{Im})}- \frac{\phi }{\lambda }}\) and the price demanded by the exporter is \(\check{p}=\hat{p}-\frac{\phi }{\lambda }+\frac{\phi }{(1+\bar{r}_{Im})}\). In this pooling equilibrium, both high- and low-quality importers extend the same share of CIA. The bank is unable to infer the type of the importer from this signal and sticks to its ex-ante belief, \(Prob\left( H\right) =\mu \). It extends additional bank credit at the interest rate \(\left( \frac{1+\bar{r}_B}{\lambda \mu }\right) \).

Proof

See the Online Appendix.

For the pooling equilibrium in which \(\alpha ^{Pool}=\frac{\phi /(1+\bar{r}_{Im})}{\hat{p}+ \frac{\phi }{(1+\bar{r}_{Im})}- \frac{\phi }{\lambda }}\), we can derive the following productivity threshold:

Comparing the minimum productivity thresholds in the different financing scenarios, we derive the following proposition.

Proposition 3

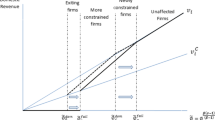

The productivity thresholds can be uniquely ranked:

Thus, we can identify four groups of firms. (1) Firms with \(\left( 1+\beta \right) \ge \left( 1+\beta \right) _{Ex}^{BC}\) can export in every financing scenario. (2) Firms with \(\left( 1+\beta \right) _{Ex}^{Pool}\le \left( 1+\beta \right) <\left( 1+\beta \right) _{Ex}^{BC}\) can export if CIA is given, either in the separating or the pooling equilibrium. (3) Firms with \(\left( 1+\beta \right) _{Ex}^{Sep}\le \left( 1+\beta \right) <\left( 1+\beta \right) _{Ex}^{Pool}\) can export only in the separating equilibrium if the signal via CIA is informative. (4) Firms with \(\left( 1+\beta \right) <\left( 1+\beta \right) _{Ex}^{Sep}\) cannot export at all.

Proof

See the Online Appendix.

Figure 1 gives a graphical representation of the ranking of the productivity thresholds for the three different financing options. Proposition 3 implies that if CIA financing is available, less productive firms in the second and third group can export that would not have been able to do so with pure bank financing only. These firms benefit from the availability of CIA. Firms in the fourth group cannot export even if CIA is available. Firms in the third group depend on an informative signal that eliminates the adverse selection problem. Therefore, these firms play the separating perfect Bayesian Equilibrium. In contrast, firms in the second group have a high enough productivity level to export even if the adverse selection problem is not eliminated and can export under both equilibria. However, they cannot export with pure bank financing only. This is due to the fact that incentives for opportunistic behavior are stronger without CIA so that an exporter has to set a lower price for his good to prevent moral hazard by the importer. Firms in the first group do not depend on CIA availability since they are productive enough to export with pure bank financing only. Interestingly, even these firms which have access to bank financing prefer to use CIA. This is shown in the following proposition.

Proposition 4

Even if firms are able to export using pure bank financing, i.e., if \(\left( 1+\beta \right) \ge \left( 1+\beta \right) _{Ex}^{BC}\), they prefer partial CIA financing to pure bank financing.

Proof

See the Online Appendix.

Even very productive firms generate strictly lower expected profits with pure bank financing than with partial CIA financing. This is due to the fact that any small amount of CIA provided reduces the importer’s incentive to divert the good. Consequently, the exporter can set a higher price and generate higher expected profits from partial CIA financing.

Proposition 5

Firms with \((1+\beta )\ge \left( 1+\beta \right) _{Ex}^{Pool}\) can export under both the separating and the pooling equilibrium. They prefer to play the separating (pooling) equilibrium if quality uncertainty is low (high) and the importer’s refinancing costs are high (low). The higher the productivity of the firm, the greater the parameter space in which the pooling equilibrium is preferred by the exporters.

Proof

See the Online Appendix.

If the importer’s refinancing costs are high, the exporter’s expected profits are higher in the separating equilibrium since the informative signal compensates for the relatively lower price firms receive from the importer. In contrast, expected profits are higher in the pooling (separating) equilibrium if uncertainty is high (low). This result seems counterintuitive at first. However, it is due to the fact that trade with an informative signal takes place with probability \(\mu \) only. With probability \((1-\mu )\) the importer is of low quality and hence not willing to send the informative signal which means that the transaction does not take place. An uninformative signal in a pooling equilibrium is sent by both types of importers, instead. Therefore, firms prefer receiving at least a small (uninformative) share of CIA upfront than receiving nothing if it is very likely that they trade with a low-quality importer (\(\mu \) is low). This effect is reinforced for more productive firms since more productive firms have lower production costs and can better absorb losses when trading with a low-quality importer. To summarize, what emerges from our model is the following:

The availability of CIA increases the profitability of exporting and hence increases the probability of exporting. This effect is particularly relevant for less productive firms.

CIA is beneficial to firms since it reduces uncertainty with regard to foreign trading partners and it makes moral hazard less attractive to the firm paying in advance. Both effects increase the profits from exporting which implies that all firms prefer to use a combination of CIA and bank credit. However, considering a firm’s ability to export, the provision of CIA is particularly beneficial to less productive firms since these firms cannot export in the absence of CIA. Therefore, we expect the positive effect of CIA on the export probability of firms to work mainly through the effect of less productive firms.

3 Data and summary statistics

To test our prediction, we use data from the Business Environment and Enterprise Performance Survey (BEEPS) on 1,196 German firms in 2004. BEEPS was developed jointly by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development and the World Bank Group to analyze the business environment of firms and to link it with firm performance. In 2004, cross-sectional data on German firms was collected. By using stratified random sampling, a high representativeness of the sample is achieved. Specifically, the sample is designed so that the population composition with regard to sectors, firm size, ownership, foreign activity, and location is captured.Footnote 13 Table 1 provides the decomposition of firms according to sectors for our sample. A detailed description of all variables included in our analysis can be found in Table 2. Panel A of Table 3 provides average sample characteristics. The median number of 12 employees per firm and the median of expected sales of 1,200,000 euro in the sample correspond quite well to the German population averages: according to data from the Statistical Yearbook 2007 for the Federal Republic of Germany, the average number of employees is 13 and average sales amount to 1,230,000 euro in Germany in 2004.

The main advantage of this dataset is that it provides us with a precise measure of the use of CIA by firms. More specifically, firms are asked what percentage of their sales in value terms were paid before delivery from their customers over the last 12 months. Thus, we do not have to rely on a proxy such as trade payables which is often used in the trade credit literature when only balance sheet data is available. However, we cannot single out CIA related to exporting activities compared to domestic activities since transaction level data is not available in the survey. Thus, we restrict our analysis to linking the overall use of CIA by firms to their export participation decision. Data on the exporting activities by firms is given in terms of export shares of total sales ranging from 0 to 90 % in our dataset. We classify a firm as an exporter if it sells a positive amount of its sales abroad.

About 16 % of all firms generate a positive share of their sales abroad (Panel A, Table 3), a share that is slightly higher than the population average for 2004 (12 %, according to data from the Institut für Mittelstandsforschung). A look at the average use of CIA in the sample reveals that more than one third of all firms receive prepayments from their customers. The sample mean share of sales received before delivery of the good is 7 %. This seems rather low but is due to the large number of firms who do not receive CIA. If we only consider firms that receive a positive share of CIA, the average increases to 21 %. This implies that the remaining 79 % of total sales is either paid on time or after delivery by customers.

Panel B of Table 3 displays differences in CIA use by exporters versus non-exporters. Strikingly, exporters distinctly use CIA more extensively than non-exporters. About 44 % of all exporters receive a positive share of their sales in advance, whereas only 34 % of all non-exporters obtain advance payment. The average share of CIA received is very similar for both groups and only marginally higher for exporters. Since our data does not allow us to determine whether CIA is used to finance a domestic or an export transaction, we are concerned that the higher use of CIA by exporters is simply driven by the significantly larger size of exporters in terms of number of employees and scope of operations. We therefore split firms into size quartiles according to their number of employees and check whether exporters still use CIA more extensively than non-exporters within the same size quartiles. We find that within the same size quartile, relatively more exporters than non-exporters receive CIA payments except within the highest size quartile. Note that the low number of exporters in each size quartile makes it difficult to observe significant positive differences although the differences are quite large. Other well-known characteristics of exporters are reflected in the data as well: exporters are older, have higher sales per worker (labor productivity), and rather tend to be foreign-owned.

These descriptive statistics suggest that CIA financing plays an important role for internationally active firms. Our theoretical model provides an explanation for these findings which we put to an empirical test in the following section.

4 Empirical analysis

4.1 Empirical strategy: simple probit model

Our model prediction states that access to CIA financing facilitates entry into exporting since asymmetric information problems are reduced. This effect should be driven through the increased export performance of less-productive firms since high-productive firms can export even in the absence of CIA. As stated in our model, a firm is able to participate in exporting if it generates positive profits from exporting, \(\pi _{Ex}>0\). The firm’s profits from exporting depend on the financing options available to the firm, partial CIA versus pure bank financing, its own productivity level as well as other firm characteristics. Thus, we rewrite \(\pi _{Ex}\) as

where \(CIArec_{i}\) measures the firm’s use of CIA financing. We employ two measures of CIA financing. The first is a binary indicator, \(DCIArec\), equal to 1 if the firm receives a positive amount of CIA and equal to 0 otherwise. In the latter case, the firm receives its sales either on time or after delivery which implies that the firm has to rely on other sources of financing such as bank credit financing. The second is the log percentage share of total sales received in advance, \(LogCIArec\). We take the log value to obtain a less skewed distribution of our key regressor and because average marginal effects can be interpreted as elasticities. Since we do not want to lose all firms with a zero share of CIA, we assign zero observations a value that is slightly lower than zero. A lower value of \(LogCIArec\) implies that the firm has to rely on other financing sources to a greater extent. Log labor productivity, \(LogLabprod\), is defined as the log of sales over employees and proxies for the firm’s own level of efficiency. Additional firm level controls that influence the export decision of a firm are included in the vector \(\mathbf {C_{i}}\). \(\epsilon _{i}\) denotes the error term. We do not observe the true profits from exporting \(\pi ^*_{i}\) of a firm, but its export status \(Exp_{i}\). It is defined as a binary indicator equal to 1 if the firm generates positive profits from exporting and 0 otherwise:

Assuming a standard normal distribution of \(\epsilon _i\) we can write the probability to export for firm \(i\) as:

where \(\Phi \) denotes the standard normal cdf of the error term. According to our model, the availability of CIA increases the profits from exporting \(\pi _i^*\) and thus, we expect the effect of CIA on the export probability to be positive, \(\beta _1>0\). The same holds for the productivity level of the firm, \(\beta _2>0\).

\(\mathbf {C_i}\) contains several control variables that influence the export decision of firms and are commonly used in the literature. We follow Minetti and Zhu (2011) and control for reputation and size effects by including the log of firms’ age (\(LogAge\)) and the log number of employees (\(LogSize\)). Moreover, the percentage of the workforce with a university education or higher, \(Univeduc\), is added to control for human capital effects. Older and larger firms are usually expected to have a higher export probability, as well as firms that possess a more highly educated workforce. We take the competitive environment of the firm into account by controlling for the degree of national and international competition that the firm faces. \(CompNum\) gives the number of national competitors of the firm. It ranges from 0 to 4 where 4 is coded as 4 or more competitors in the national market. \(ForPressure\) captures the extent of foreign competition. It is defined as a binary indicator equal to 1 if the firm states to be fairly or very much influenced by competition from foreign competitors when making key decisions with regard to reducing the production costs of existing products or services. It is equal to 0 if foreign pressure is not at all or only slightly important to the decision process of the firm. The influence of competition on a firm’s export decision is ambivalent. On the one hand, stronger competition can deter firms from entering the export market. On the other hand, it can hint at the existence of a larger market and growth opportunities to the firm by going international. Last but not least, we control for foreign ownership since foreign-owned firms are more likely to export (Greenaway et al. 2007). \(Foreign\) is a dummy equal to 1 if at least 10 % of the firm are owned by a foreign entity. Sector-specific effects are included in all specifications, as well.

To test our hypothesis, we first estimate (12) via a binary probit model. Table 4 presents the corresponding results. For ease of interpretation, we display average marginal effects instead of the regression coefficients. CIA has a positive and highly significant effect on the export participation of firms. Firms that receive a positive share of CIA have a 6 % higher probability to export than firms that are not paid in advance by their customers (column 1). Likewise, a 1 % higher share of sales paid in advance is associated with a 1.6 % increase in a firm’s probability to export (column 2). We take this as first evidence for the positive relationship between CIA and exporting as postulated in our model. With regard to the other estimates, we confirm prior findings of the literature. Larger and more productive firms have a higher export probability, as well as foreign-owned firms and firms equipped with a more highly educated workforce. In contrast, older firms do not participate significantly more often in exporting. The effect of the number of domestic competitors is positive but not significant, either. Instead, we find a strong positive influence of pressure from foreign competitors. This may reflect growth opportunities available in the foreign market where firms make use of scale effects.

In columns (3) and (4) of Table 4, we additionally control for the price to cost ratio of a firm, \(Markup\). \(Markup\) is defined as the margin by which the firm’s sales price exceeds the operating costs. This allows us to control more rigorously for the competitive environment of firms. Firms that are more profitable should be better able to enter new export markets and thus we expect a positive influence on the export status. As columns (3) and (4) show, \(Markup\) has indeed a positive and significant effect on the export participation but its inclusion does not affect our other results.

4.2 Empirical strategy—IV estimation

Up to now, we have ignored potential endogeneity in our key regressor, \(CIArec\). Whether a firm receives CIA financing from its customers very likely is not randomly assigned across firms. If there are unobserved factors that affect both the export decision of a firm and the decision to use CIA financing the estimated coefficient \(\beta _1\) is biased. One example for the selection bias is uncertainty with regard to the importer’s type, captured by the parameter \(\mu \) in our model. Higher uncertainty with regard to the trading partner’s ability to repay hinders entry into exporting since exporting becomes less profitable. Likewise, higher uncertainty makes the use of CIA more attractive in order to alleviate asymmetric information. Consequently, not controlling for the level of uncertainty may lead to a downward bias of our results. In this subsection, we address endogeneity in our key interesting variable by instrumental variable estimation.

To find a suitable instrument, we make use of information on the relationship between firms and their customers. In the survey, the specificity of the main product or service sold by the firm is addressed in one question. Firms are asked how their customers react if the firm raises the price of its main product or service line by 10 % assuming that its competitors maintained their current prices. Out of the answers to this question we construct the ordinal variable \(Specificity\):

-

1

many of the customers would buy from competitors instead,

-

2

customers would continue to buy from the firm, but at much lower quantities,

-

3

customers would continue to buy from the firm, but at slightly lower quantities,

-

4

customers would continue to buy from the firm in the same quantities as before.

\(Specificity\) thus measures the price elasticity of demand that the firm faces or, in other words, the bargaining power that the firm has vis-à-vis its customers. A higher value of the variable indicates a higher bargaining power or a lower elasticity of demand. We expect a positive relationship between \(Specificity\) and the use of CIA. A low elasticity of demand reflects a high specificity of the good or service sold such that customers depend on the input. Consequently, these customers have a higher incentive to comply with CIA requirements by the firm. Mateut (2012) provides empirical evidence on the relationship between goods’ characteristics and customer prepayments for French firms. She finds that downstream firms that sell a differentiated good receive larger prepayments from their customers than firms that sell standardized goods. One concern is that \(Specificity\) could have a direct effect on the export participation of firms since it is related to the substitution elasticity of demand. As Chaney (2008) shows, entry into exporting negatively depends on the elasticity of substitution between goods. According to his model, firms are more (less) likely to enter a foreign market if varieties are less (more) substitutable.Footnote 14 In this case, we would expect a positive relationship between the instrument and exporting and thus IV estimation would overstate the effect of CIA financing. Since we cannot fully eliminate this concern, we consider the IV results as an upper bound for the effect of CIA financing.

Since \(DCIArec\) is binary, we apply the recursive bivariate probit model to estimate the effect of CIA on export participation in our first specification. The recursive bivariate probit model simultaneously estimates two probit models via maximum likelihood. The first equation models the effect of the binary endogenous regressor and other controls on the outcome. The second equation models the endogenous regressor as a function of the instrument and the other controls. The error terms of both equations are assumed to be correlated due to the presence of unobserved factors.Footnote 15 In our case, we jointly estimate the export probability and the probability of a firm to receive CIA by its customers. The first equation is given in (12). The second equation describes the probability to receive CIA as follows:

where \(Z_{i}\) denotes the instrument and the error term \(u_i\) is assumed to be standard normally distributed. \(\epsilon _i\) and \(u_i\) are jointly normally distributed with mean zero, a variance of 1 and a correlation coefficient of \(\rho \).

When using the continuous measure of CIA received, \(LogCIArec_i\), we replace Eq. (13) with the following reduced form specification:

Equations (12) and (14) are jointly estimated via maximum likelihood under the assumption that \(\epsilon _i, v_{i}\sim N\left( {0, \mathbf \sum }\right) \) and \(\sigma _{11}=1\).

Columns (1) and (2) of Table 5 provide the coefficients from jointly estimating Eqs. (12) and (13) via the bivariate probit model. As expected, \(Specificity\) has a strong and positive impact on a firm’s probability to receive CIA (column 2). In other words, the higher the bargaining power of the firm, the more likely it is to receive CIA. Moreover, we find that younger firms are more likely to use CIA. This may reflect that these firms probably do not have built up a reputation with banks and are more constrained in their access to traditional forms of finance. Firm size and the level of labor productivity also increase a firm’s likelihood to receive CIA. Both findings are in line with results on CIA use by French firms (Mateut 2012). In addition, we find that firms with a more highly educated workforce also tend to use prepayment financing more often. In column (1), the estimates for Eq. (12) are displayed. We observe a strong and positive influence of CIA received on the export participation decision of firms. Interestingly, the effect has more than tripled compared to the simple probit model estimate. Calculating the average treatment effect (ATE) of CIA received on the export probability of firms, we find that CIA financing increases the likelihood of firms to export on average by 25 %.Footnote 16 The Wald test of zero correlation between \(\epsilon \) and \(u\) yields a significant negative correlation \(\hat{\rho }\) at the 1 % level suggesting that we cannot consider the use of CIA by firms as exogenous.

In the last two columns, we again control for the price to cost ratio, \(Markup\). The price to cost ratio of a firm does not affect its likelihood to receive CIA but positively impacts on its export status. Controlling more rigorously for the competitive environment of firms leaves our results basically unchanged. The influence of \(Specificity\) on \(DCIArec\) decreases only slightly (column 5) as does the effect of \(DCIArec\) on the probability to export (column 4).

Next, we provide the results from the instrumental variable probit estimation of Eqs. (12) and (14) in Table 6. In contrast to the simple probit model estimates in Table 4, columns (2) and (4), IV estimation leads to a more precise and highly significant coefficient. Calculating the average marginal effect (AME), we find that a 1% increase in the share of CIA received on total sales raises firms’ export participation probability between 14 and 15 %, depending on the set of competition controls (columns 1 and 3). The Wald test rejects exogeneity of \(LogCIArec\) at the 1 % significance level and supports the choice of our instrumentation strategy.Footnote 17

Taken together, our results strongly support our hypothesis that CIA financing fosters the export participation of firms. If we do not control for potential endogeneity, the effect of CIA on exporting is considerably smaller hinting at a downward bias due to omitted variables. Applying an instrument that accounts for non-random use of CIA by firms, we establish a statistically and economically meaningful effect of CIA financing on exporting. As we have argued before, the IV estimation results can be considered as an upper bound of the effect of CIA on exporting, whereas the results without controlling for endogeneity can be considered as a lower bound.

4.3 Effect of CIA financing on export participation for different subsets of firms

So far, we have assumed that the effect of CIA financing on the export participation decision of firms is constant across firms. However, according to our model, we expect the positive effect of CIA financing to be driven mainly through the effect for less productive firms since high-productivity firms can export even if only pure bank financing is available. In this subsection, we therefore explicitly test for heterogeneous effects of prepayment financing on exporting for low- and high-productivity firms. In addition, we apply several other concepts that express firms’ difficulties in entering the export market. We expect the export fostering effect of CIA to be particularly strong for firms that more strongly suffer from these difficulties. In doing so, we rely on the specification with the continuous measure of CIA as key regressor (Eqs. 12, 14) because the recursive bivariate probit model becomes less computationally feasible if the number of observations drops. Furthermore, we use the most rigorous specification that includes all competition controls. The results of this exercise can be found in Table 7.

We first split firms according to their level of labor productivity to test our model prediction. As cut-off, we choose the median level of labor productivity. In line with our model we expect the export fostering effect of CIA financing to be particularly strong for firms with below median productivity. The results in Table 7, rows (1) and (2) confirm our conjecture. The effect of CIA on the export probability of less productive firms is highly significant and larger than the corresponding effect for firms at the upper end of the productivity distribution: a 1 % increase in the share of CIA received raises the export probability of low-productivity firms by 16 % whereas high-productivity firms enjoy an additional increase of 13 %.

Alternatively, we divide our sample in small and large firms with the median number of employees as cut-off. Assuming that smaller firms experience greater difficulties in entering the export market, we expect a stronger fostering effect of CIA on the export probability for firms below the median size level. The findings in rows (3) and (4) suggest that the effect of CIA on the export participation is indeed driven by small firms: small firms that experience a 1 % increase in CIA shares can increase their export probability by about 15 %. In contrast, larger firms do not significantly benefit from additional CIA financing.

In rows (5) and (6), we test for different effects for foreign-owned and domestic firms. Starting from the empirical finding that foreign-owned firms are more likely to export (Greenaway et al. 2007) we expect the influence of CIA to be stronger for domestically owned firms. As our results show, this is indeed the case. Domestically owned firms strongly benefit from higher CIA financing whereas the export probability of foreign-owned firms is not significantly affected by CIA financing. One potential explanation for this finding is that foreign-owned firms have better access to foreign markets via their foreign parent company. Thus, they are less affected by information asymmetries and do not depend on CIA financing in order to start exporting.

Next, we analyze CIA effects for firms with different financing needs. As several studies have forcefully shown, financial constraints strongly deter firms from exporting (Manova 2013; Minetti and Zhu 2011; Chaney 2013). In Manova (2013), financial constraints increase the cut-off for exporting and thus prevent the least productive firms from exporting. Since CIA financing is especially relevant for the least productive firms, we expect financially constrained firms or firms with greater financing needs to particularly benefit from higher CIA financing.

To test this presumption, we first divide firms according to their access to bank financing. The survey allows identifying firms that do not receive a bank loan although they have a positive demand for it. In the survey, firms are asked whether they recently obtained a bank loan. Firms that state that they do not currently possess a bank loan are asked to state the reasons: potential answers are no need for a loan, downturn of the loan application or discouragement from applying for the loan for several reasons. We follow Hainz and Nabokin (2013) and divide firms into two subgroups according to their demand and access to credit. In doing so, we only consider firms that state a demand for credit, which is true for 78 % of all firms in our sample. We then split these firms according to whether they currently possess a loan or not. Firms that do not possess a loan have either faced a downturn of their application or did not apply for a loan because they were discouraged from applying due to high interest rates, burdensome application procedures or because they thought the loan application would be turned down anyways. We expect firms that do not possess a loan but have demand for a loan to benefit more from additional CIA financing than firms whose loan application was successful. Our results confirm this conjecture: firms that require external finance but do not obtain a bank loan can raise their export probability by about 30 % if CIA received increases by 1 %, row (7). In contrast, the partial effect for firms with access to a bank loan is only half of that for firms without access, row (8). This strongly points to substitutional CIA financing by customers in order to facilitate entry into exporting.

To gauge the extent of firms’ financial needs, we finally split the sample according to the real growth rate of material input costs. Firms with above median growth of material input costs very likely require additional financing to cover their higher input costs. We expect these firms to benefit more strongly from additional CIA financing. High growth firms experience a rise in their export probability by about 17 % for every 1 % increase in CIA financing, row (10). In contrast, the average marginal effect for low growth firms is smaller and only marginally statistically significant, row (9).

5 Conclusion

Our findings suggest that prepayment financing between firms can be very beneficial. CIA serves as a credible signal of quality and reduces part of the high uncertainty in international trade. If asymmetric information makes exporting less profitable, CIA can help firms overcome productivity frictions if other firms signal their reliability in form of CIA. Despite higher implied costs, this in turn can facilitate entry into exporting, in particular for less productive firms. We confirm our predictions for a sample of German firms. Although the German credit market is rather well-developed, German firms greatly benefit from access to CIA financing in terms of their export participation. We expect the positive effects of CIA financing to be especially relevant in a situation of global monetary contractions when firms experience severe difficulties in obtaining bank-intermediated trade finance. An analysis of this relationship is left for future work.

Notes

In the literature, the term trade credit is sometimes used for credits extended by a bank to support a trade transaction. When using the term trade credit, we exclusively refer to inter-firm credits that are extended between firms without any financial intermediation.

For an extensive overview of further trade credit motives, see e.g., Fisman and Love (2003).

In long-term customer-buyer relationships, CIA and supplier credit financing can also become complementary. Antràs and Foley (2011) show that paying in advance can help buyers to receive a supplier credit from the seller in the future. A similar observation is made by Mateut and Zanchettin (2013). For a panel of French firms, they find that small sellers of differentiated goods and exporters of standardized goods tend to grant more trade credit if they receive CIA from their customers.

In a companion paper, Engemann et al. (2014), we use a similar theoretical framework to explore the relationship between bank credits and supplier credits for exporting firms. Additionally, we provide empirical evidence of the complementary relationship between supplier credits and bank credits for German exporters that are financially constrained.

Since we are interested only in whether a firm can export at all, we exclude domestic transactions from our analysis.

The choice of a convex cost function instead of downward sloping demand and constant marginal costs of production is made for simplicity. It allows us to assume an exogenous market price for the exporter’s good and we can abstract from choosing a particular market structure.

Including moral hazard is necessary to have type uncertainty in our model. Without any possibility to divert the good, a low-quality importer would not take part in trade.

Araujo and Ornelas (2007) also model type uncertainty of exporters and importers in international trade. They focus on improvements in institutional quality to overcome asymmetric information.

Survey evidence also suggests that inter-firm credits dominate the financing of international transactions (IMF 2009). Less than 40 % of international transactions is financed via bank-intermediated trade finance such as letters of credits which can be seen as a form of payment at delivery. Due to the lower prevalence of letters of credit and since we cannot observe this form of trade finance in our data, we abstract from analysing payment at delivery.

We abstract from two-sided information asymmetries because the focus of our paper is to show how advance payments influence the export decision of firms. Including information asymmetries with respect to the exporter’s type and behavior as well would certainly lower the overall attractiveness of cash in advance payments. Models of how information asymmetries impact on the choice of the optimal trade credit contract can be found in Ahn (2011), Antràs and Foley (2011), or Schmidt-Eisenlohr (2013).

Sectors included in the sample are mining and quarrying, construction, manufacturing, transportation, storage and communications, wholesale, retail and repairs, real estate and business service, hotels and restaurants, and other community, social and personal activities. Sectors that are subject to government price regulation and prudential supervision like banking, electric power, rail transport, and water and waste water are excluded.

We thank an anonymous referee for bringing this concern to our attention.

For more details on the estimation procedure, see e.g., Minetti and Zhu (2011) who use this estimation approach to address potential endogeneity in a trade context.

The average treatment effect of CIA received on exporting is given by the following formula in Wooldridge (2010), p. 594: \(\Phi (\alpha +\beta +\mathbf {\gamma C_i})-\Phi (\alpha +\mathbf {\gamma C_i})\).

To ensure that the considerable increase in the estimated effect of CIA financing does not stem from the non-linearity underlying the recursive bivariate probit or the instrumental probit model, we also checked whether we receive similar results from two-stage-least-squares (2SLS) estimations. 2SLS estimations yield an even stronger relationship between CIA received and the export participation of a firm in all regression specifications. However, the estimations perform worse in terms of model fit and key statistics and are therefore left out of the analysis.

References

Ahn, J. (2011). A theory of domestic and international trade finance. (IMF Working Papers 11/262). Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

Amiti, M., & Weinstein, D. E. (2011). Exports and financial shocks. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 126(4), 1841–1877.

Antràs, P., & Foley, C. F. (2011). Poultry in motion: A study of international trade finance practices. (NBER Working Paper 17091). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Araujo, L., & Ornelas, E. (2007). Trust-based trade. (CEP Discussion Paper 0820). Centre for Economic Performance, London School of Economics.

Auboin, M. (2009). Boosting the availability of trade finance in the current crisis: Background analysis for a substantial G20 package. (CEPR Policy Insight 35). London: Centre for Economic Policy Research.

Auboin, M., & Engemann, M. (2014). Testing the trade credit and trade link: Evidence from data on export credit insurance. Review of World Economics, 150, 4. doi:10.1007/s10290-014-0195-4.

Biais, B., & Gollier, C. (1997). Trade credit and credit rationing. Review of Financial Studies, 10 (4), 903–937.

Burkart, M., & Ellingsen, T. (2004). In-kind finance: A theory of trade credit. American Economic Review, 94(3), 569–590.

Chaney, T. (2008). Distorted gravity: The intensive and extensive margins of international trade. American Economic Review, 98(4), 1707–1721.

Chaney, T. (2013). Liquidity constrained exporters. (NBER Working Paper 19170). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Chor, D., & Manova, K. (2012). Off the cliff and back: Credit conditions and international trade during the global financial crisis. Journal of International Economics, 87 (1), 117–133.

Engemann, M., Eck, K., & Schnitzer, M. (2014). Trade credits and bank credits in international trade: Substitutes or complements? The World Economy. doi:10.1111/twec.12167.

Fisman, R., & Love, I. (2003). Trade credit, financial intermediary development, and industry growth. The Journal of Finance, 58 (1), 353–374.

Giannetti, M., Burkart, M., & Ellingsen, T. (2011). What you sell is what you lend? Explaining trade credit contracts. The Review of Financial Studies, 24 (4), 1261–1298.

Glady, N., & Potin, J. (2011). Bank intermediation and default risk in international trade-theory and evidence. Mimeo: ESSEC Business School.

Greenaway, D., Guariglia, A., & Kneller, R. (2007). Financial factors and exporting decisions. Journal of International Economics, 73 (2), 377–395.

Hainz, C., & Nabokin, T. (2013). Measurement and determinants of access to loans. (CESifo Working Paper Series No. 4190). Munich: CESifo Group.

Hoefele, A., Schmidt-Eisenlohr, T., & Yu, Z. (2013). Payment choice in international trade: Theory and evidence from cross-country firm level data. (CESifo Working Paper Series 4350). Munich: CESifo Group.

Iacovone, L., & Zavacka, V. (2009). Banking crises and exports: Lessons from the past. (Policy Research Working Paper Series 5016). Washington, DC: The World Bank.

IMF (2009). Sustaining the recovery. World Economic and Financial Survey, Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

Klapper, L., Laeven, L., & Rajan, R. G. (2012). Trade credit contracts. Review of Financial Studies, 23(3), 838–867.

Lee, Y. W., & Stowe, J. D. (1993). Product risk, asymmetric information, and trade credit. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 28 (2), 285–300.

Long, M. S., Malitz, I. B., & Ravid, S. A. (1993). Trade credit, quality guarantees, and product marketability. Financial Management, 22 (4), 117–127.

Manova, K. (2013). Credit constraints, heterogeneous firms, and international trade. Review of Economic Studies, 80 (2), 711–744.

Mateut, S. (2012). Reverse trade credit or default risk? Explaining the use of prepayments by firms. (Discussion Papers 11/12). University of Nottingham, Centre for Finance, Credit and Macroeconomics.

Mateut, S., Bougheas, S., & Mizen, P. (2006). Trade credit, bank lending, and monetary policy transmission. European Economic Review, 50(3), 603–629.

Mateut, S., & Zanchettin, P. (2013). Credit sales and advance payments: Substitutes or complements? Economics Letters, 118 (1), 173–176.

Melitz, M. J. (2003). The impact of trade on intra-industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity. Econometrica, 71(6), 1695–1725.

Minetti, R., & Zhu, S. C. (2011). Credit constraints and firm export: Microeconomic evidence from Italy. Journal of International Economics, 83(2), 109–125.

Olsen, M. G. (2011). Banks in international trade: Incomplete international contract enforcement and reputation. Mimeo: Harvard University.

Petersen, M. A., & Rajan, R. G. (1997). Trade credit: Theories and evidence. Review of Financial Studies, 10(3), 661–691.

Schmidt-Eisenlohr, T. (2013). Towards a theory of trade finance. Journal of International Economics, 91(1), 96–112.

Welch, B. L. (1947). The generalization of “student’s” problem when several different population variances are involved. Biometrika, 34, 28–35.

Wooldridge, J. (2010). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Bavarian Graduate Program in Economics and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (German Science Foundation) under SFB-Transregio 15 for financial support. We are grateful to Kalina Manova, Ralph Ossa, Till von Wachter, Silja Baller, and several seminar and conference participants for helpful comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

About this article

Cite this article

Eck, K., Engemann, M. & Schnitzer, M. How trade credits foster exporting. Rev World Econ 151, 73–101 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-014-0203-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-014-0203-8