Abstract

Poor oral health conditions are well documented in the institutionalized elderly, but the literature is lacking research on relationships between dementia and periodontal health in nursing home residents. The purpose of this cohort study, therefore, was to assess whether dementia is associated with poor oral health/denture hygiene and an increased risk of periodontal disease in the institutionalized elderly. A total of 219 participants were assessed using the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) to determine cognitive state. According to the MMSE outcome, participants scoring ≤20 were assigned to dementia group (D) and those scoring >20 to the non-dementia group (ND), respectively. For each of the groups D and ND, Gingival Bleeding Index (GBI) and Denture Hygiene Index (DHI) linear regression models were used with the confounders age, gender, dementia, number of comorbidities and number of permanent medications. To assess the risk factors for severe periodontitis as measured by the Community Index of Periodontal Treatment Needs, a logistic regression analysis was performed. Statistical analysis revealed no significant differences of GBI as well of DHI for demented and healthy subjects (p > 0.05). Severe periodontitis was detected in 66 % of participants with dementia. The logistic regression showed a 2.9 times increased risk among demented participants (p = 0.006). Oral hygiene, denture hygiene and periodontal health are poor in nursing home residents. The severity of oral problems, primarily periodontitis, seems to be enhanced in subjects suffering from dementia. Longitudinal observations are needed to clarify the cause–reaction relationship.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The proportion of elderly is increasing rapidly in Western countries. This demographic shift will lead to a higher number of people which will have to be cared for in nursing homes within the next decades. Poor oral health conditions are well documented in this specific community. Compared to elderly not living in nursing homes, a larger prevalence of substantial dental plaque accumulation and caries has been detected in nursing home residents [1–3]. Literature further indicates that periodontal disease is very common in this population [4]. However, seniors in need of care frequently face various other systemic illnesses and polypharmacy which might be intercorrelated with poor oral health [5].

The previous research revealed that cognitive and functional impairment are highly prevalent in nursing home residents [6, 7]. Many factors contribute to cognitive impairment in the elderly. It has been pointed out that cardiovascular disease, diabetes, alcohol and smoking may be risk factors for a decreased cognitive state, whilst social integration and educational background seem to be protective variables [8]. Nonetheless, in the vast majority of cases, cognitive impairment of the elderly is a symptom of dementia which is very common in old age. The prevalence of dementia among nursing home residents 50 years and above is stated to be approximately 50 %. Besides cognitive and motor impairments, dementia additionally comprises of behavioral and psychological changes like anxiety and aggressive behavior [9–11]. In conclusion, all these factors limit the ability to independently perform normal daily activities, including personal care and oral hygiene. Behavioral disturbances hinder care givers from providing sufficient care, even though the elderly are especially in need of nursing help [12]. The previous studies acknowledged that dementia promotes to poor oral hygiene [7, 13] and health, namely, caries incidence and periodontal disease [14–16].

Up to now, information on the associations between dementia and gingivitis/periodontitis in institutionalized communities is rare. A previous research article reported comparable denture hygiene, caries increments and gingival inflammation for people with and without dementia but higher levels of mean plaque and periodontal treatment needs in a sample of 93 elderly living in four nursing homes of one care society [17]. Larger sample sizes would be valuable to verify these results and to generate multivariate risk models for severe periodontitis because adequate periodontal health is not only an important determinant regarding the chewing function and, therefore, nutrition, but also it is important for general health. Poor oral hygiene leads to a higher risk for pneumonia [17, 18], and periodontitis promotes cardiovascular diseases, stroke and diabetes [19–21].

The objective of this cohort study was, therefore, to assess whether dementia is associated with poor oral health/denture hygiene and an increased risk of periodontal disease in the institutionalized elderly.

Materials and methods

Participants

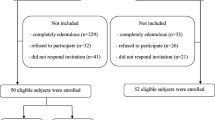

This cohort study was approved by the local review board of the University of Heidelberg (No. 002/2012) and was in accordance to the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was conducted in 14 nursing homes located in the federal state of Baden-Württemberg (Germany), selected by the Ministry of Social Affairs to be representative for all homes in Baden-Württemberg. For each nursing home, an information event was held to introduce the contents of the study. Potential participants received written and oral information. The only inclusion criteria were a consent form, signed by the participant or her/his legal guardian. 277 participants agreed to participate and were included in the study (final sample). This paper includes information of 93 participants in four nursing homes of one care society in the city of Mannheim, Baden-Württemberg, which have been reported elsewhere [17].

Demographic data

Medical records were studied to determine sex, age, number of comorbidities and routinely taken medications. The intake of any anticoagulative medications was recorded.

Assessment of dementia

Participants were screened for dementia using the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE). Participants were asked to solve 30 tasks involving dimensions orientation, short-time memory, arithmetic tasks, language use/comprehension and basic motor skills. Each single exercise was rated whether with “0” (failed) or “1” (completed), respectively [22]. Consequently, participants who were successful in all exercises scored 30. In the literature, participants scoring equal to or below 20 are considered to suffer from dementia [22]. On the basis of the MMSE outcome, participants were assigned to two groups by an independent dentist not involved in the dental assessments.

Dental examinations

The evaluation of oral conditions was performed by two examiners who were trained at the Department of Prosthodontics prior to the investigations. In addition, a reliability assessment was performed in a sample of 15 study participants. For that purpose, these nursing home residents were examined twice by the examiners; performing this, the examiners independently evaluated and documented each of the dental target variables (see below). Agreement within all target indices was found to be Cronbach’s alpha >0.9. The dental target variables were the gingival bleeding index (GBI, 23), the periodontal screening index [Community Index of Periodontal Treatment Needs (CPITN, 24)] and the denture hygiene index (DHI, 25). GBI was assessed using a periodontal WHO probe (CPC11.5; Hu Friedy, Tutlingen, Germany). The probe was inserted and slid through the gingival sulcus at four sites (distal, buccal, mesial and lingual) of each tooth. After approximately 10 s, the number of bleeding areas was documented and divided by the number of all tooth areas [23]. In analogy to GBI, the CPITN was also performed using a WHO probe. As an indication of periodontal health condition, CPITN includes 5 codes. 0 reflects healthy conditions, 1 and 2 gingivitis, whilst 3 (moderate) and 4 (severe) are indicative of periodontitis [24]. For the determination of DHI [25], the denture(s) of each group were divided into 10 areas. After rinsing with water, drying with gauze and tinting by use of a plaque indicator (Plaque Test; Ivoclar Vivadent, Schaan, Liechtenstein) plaque-positive areas were counted and divided by 10 to give a score ranging from 0 to 100 % [25].

Statistical evaluation

To assess dementia as a risk factor for poor oral health while adjusting for possible confounders, a logistic regression model was used to evaluate its effect on the binary indicator for the presence of CPITN code 4 and linear regression models were used to assess its effects on GBI and DHI.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS v19.0 (IBM, New York, USA).

Results

During the study, 54 of the 277 participants refused to complete the MMSE and eight participants had neither own teeth nor dentures. These participants had to be excluded from statistical analysis. Thus, the complete data of 219 participants (68.5 % female) were evaluated. Age of the participants was in mean (SD) 83.1 (9.0) with a range of 54–102 years. The mean (SD) number of comorbidities was 3.4 (2.2). Participants had in mean (SD) 6.5 (3.4) permanent medications. Mean number of remaining teeth among the total sample was 7 (8.4) and 11.9 (7.8) for only dentate participants (range 1–29 teeth). 42 % of the study population were edentulous. About 62 % of the sample were demented (MMSE ≤20) (Table 1).

Mean (SD) CPITN scores for demented (D group) and healthy (ND group) participants were 3.1 (0.7) and 2.7 (0.6), respectively (p = 0.004). Prevalence of severe periodontitis was detected in 66 % of participants with dementia. Mean (SD) GBI among the participants in D group was 53.8 (27.6) and in the ND group 48.8 (28.9) which was not significantly different (p = 0.30). For denture hygiene, no significant differences between D and ND groups were detected (Table 1).

The logistic regression on the prevalence of severe periodontitis showed a 2.9 times higher risk for demented participants to suffer from severe periodontitis (p = 0.006). A higher risk to suffer from severe periodontitis was also found for the binary variable “Coagulation inhibitors” (odds ratio 2.2; p = 0.05). For female participants, a lower risk was found in the CPITN model (odds ratio 0.4; p = 0.04). No other risk factors for severe periodontal diseases could be found (Table 2). The linear regression analysis for GBI showed that none of the variables had a significant effect on GBI (p > 0.05), with the exception of age (p = 0.03) and intake of anticoagulation inhibitors (p = 0.009) (Table 3). None of the predictors had significant association to DHI in the model (p > 0.05) (Table 3).

Discussion

The results indicate that dementia increases the risk of suffering from severe periodontitis, whilst denture hygiene and oral hygiene seem not to be closely associated with dementia. As various plaque indices only highlight a snapshot of the oral hygiene condition, more comprehensive indices like GBI—as used in this study—may record plaque accumulation for a longer period of time. However, a major drawback to GBI is that the bleeding tendency of gingival tissues can also be substantially affected by the intake of anticoagulants. This could also be confirmed in this study. However, this study found comparable GBI values for demented and non-demented participants when controlled for the intake of anticoagulative medications and is in accordance with our preliminary results [17]. In this context, research revealed some controversial findings. To date, some studies have investigated higher plaque accumulation in demented subjects in comparison to those with a normal cognitive function [7, 14]. Others have reported similar biofilm rates for these communities [26] or only between healthy subjects and dwellers with severe dementia [13]. Nonetheless, frequently, the indices used are qualitative rather than quantitative, because their application is quick which is preferable due to the reduced capacity of the elderly. Periodontal disease was ubiquitous among this sample; 89 % of the participants had at least one sextant with code 3 (moderate periodontitis) which might confirm poor oral hygiene for a long period of time [27]. Moreover, the CPITN examination revealed the risk for severe periodontitis to be approximately 3 times greater for participants with dementia. This is in accordance with the previous findings which showed a higher risk for periodontal pockets in demented subjects, even in partially community-dwelling samples [15, 28]. A previous analysis revealed higher mean CPITN scores giving evidence in the same direction [17]. Interestingly, this study also observed significant differences in terms of their numbers of natural teeth between participants with and without dementia. First, tooth loss is associated with age; the participants suffering from dementia were in mean 4 years older compared to those without dementia. Second, people with dementia are prone to a variety of oral problems, such as periodontal disease—as also found in this recent study—and caries linked to tooth loss [29, 30].

For DHI, no significant differences were detected between the two groups. This finding is in agreement with another study [13, 17]. One might explain this result by the fact that it is more convenient for the caregivers to clean dentures outside the oral cavity than cleaning teeth, especially if cognitively impaired residents show aggressive or care-resistant behavior. One might also speculate that some of the dentures examined were not frequently worn any longer by the residents or were even permanently stored in a cleansing agent.

Study limitations and strengths—basically, the findings of this study might be biased due to the participants who refused to undergo MMSE, although dental predictors have been already assessed. Nonetheless, all potential residents of the nursing homes who agreed to participate were incorporated in this study. It must be considered as a strength of this study that only two dentists who were experienced in epidemiologic surveys and proofed their inter-examiner reliability performed all the dental data collection. Both dentists were unaware of MMSE outcome (single-blinded). It should also be borne in mind that participants were not pre-selected in any way, thus this is a sample which might be considered as to be representative for South-Western Germany.

Within the limitations of this study, oral hygiene, denture hygiene and periodontal health are poor in nursing home residents. However, the severity of oral problems seems to be higher in subjects suffering from dementia. This should be considered when planning adequate care intervention. For the clarification of the direct effect of decreasing cognitive and motor function and decreasing oral health, longitudinal studies were desirable.

References

Chalmers JM, Hodge C, Fuss JM, Spencer AJ, Carter KD. The prevalence and experience of oral diseases in Adelaide nursing home residents. Aust Dent J. 2002;47:123–30.

Chalmers JM, Carter KD, Spencer AJ. Caries incidence and increments in Adelaide nursing home residents. Spec Care Dentist. 2005;25:96–105.

Montal S, Tramini P, Triay JA, Valcarcel J. Oral hygiene and the need for treatment of the dependent institutionalized elderly. Gerodontology. 2006;23:67–72.

Hopcraft MS, Morgan MV, Satur JG, Wright FA, Darby IB. Oral hygiene and periodontal disease in Victorian nursing homes. Gerodontology. 2012;29:220–8.

Fitzpatrick J. Oral health care needs of dependent older people: responsibilities of nurses and care staff. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32:1325–32.

Almomani F, Hamasha AA, Williams KB, Almomani M. Oral health status and physical, mental and cognitive disabilities among nursing home residents in Jordan. Gerodontology. 2013;. doi:10.1111/ger12053.

Chen X, Clark JJ, Naorungroj S. Oral health in nursing home residents with different cognitive statuses. Gerodontology. 2013;30:49–60.

Joshi S, Morley JE. Cognitive impairment. Med Clin N Am. 2006;90:769–87.

Grossberg GT. Diagnosis and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:3–6.

Friedlander AH, Norman DC, Mahler ME, Norman KM, Yagiela JA. Alzheimer’s disease: psychopathology, medical management and dental implications. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137:1240–51.

Neissen LC. Geriatric dentistry in the next millennium: opportunities for leadership in oral health. Gerodontology. 2000;17:3–7.

Willumsen T, Karlsen L, Naess R, Bjørntvedt S. Are the barriers to good oral hygiene in nursing homes within the nurses or the patients? Gerodontology. 2012;29:748–55.

Ribeiro GR, Costa JL, Ambrosano GM, Garcia RC. Oral health of the elderly with Alzheimer’s disease. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2012;114:338–43.

Ship JA. Oral health of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Dent Assoc. 1992;123:53–8.

Ship JA, Puckett SA. Longitudinal study on oral health in subjects with Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42:57–63.

Chalmers JM, Carter KD, Spencer AJ. Caries incidence and increments in community-living older adults with and without dementia. Gerodontology. 2002;19:80–94.

Zenthöfer A, Schröder J, Cabrera T, Rammelsberg P, Hassel AJ. Comparison of oral health among older people with and without dementia. Community Dent Health. 2014;31:27–31.

Adachi M, Ishihara K, Abe S, Okuda K. Professional oral health care by dental hygienists reduced respiratory infections in elderly persons requiring nursing care. Int J Dent Hyg. 2007;5:69–74.

Scannapieco FA. Position paper of The American Academy of Periodontology: periodontal disease as a potential risk factor for systemic diseases. J Periodontol. 1998;69:841–50.

Beck J, Garcia R, Heiss G, Vokonas PS, Offenbacher S. Periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease. J Periodontol. 1996;67:1123–37.

Dörfer CE, Becher H, Ziegler CM, Kaiser C, Lutz R, Jörss D, Lichy C, Buggle F, Bültmann S, Preusch M, Grau AJ. The association of gingivitis and periodontitis with ischemic stroke. J Clin Periodontol. 2004;31:396–401.

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–98.

Ainamo J, Bay I. Problems and proposals for recording gingivitis and plaque. Int Dent J. 1975;25:229–35.

Ainamo J, Barmes D, Beagrie G, Cutress TW, Sardo-Infirri J. Development of the World Health Organization (WHO) Community Periodontal Index of Treatment Needs (CPITN). Int Dent J. 1982;32:281–91.

Wefers KP. Der “Denture Hygiene Index”. Dent Forum. 1999;1:13–5.

Adam H, Preston AJ. The oral health of individuals with dementia in nursing homes. Gerodontology. 2006;23:99–105.

Ramfjord SP. Maintenance care for treated periodontitis patients. J Clin Periodontol. 1987;14:433–7.

Syrjälä AM, Ylöstalo P, Ruoppi P, Komulainen K, Hartikainen S, Sulkava R, Knuuttila M. Dementia and oral health among subjects aged years or older 75. Gerodontology. 2012;29:36–42.

Saito Y, Sugawara N, Yasui-Furukori N, Takahashi I, Nakaji S, Kimura H. Cognitive function and number of teeth in a community-dwelling population in Japan. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2013;12:12–20.

Grabe HJ, Schwahn C, Völzke H, Spitzer C, Freyberger HJ, John U, Mundt T, Biffar R, Kocher T. Tooth loss and cognitive impairment. J Clin Periodontol. 2009;36:550–7.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the participants in this study, for their patience, and to the participating nursing homes for their great support. We thank the Ministry of Social Affairs of Baden-Württemberg (Sozialministerium Baden-Württemberg) for financial support of the study. We also thank Lina Gorenc, Sabrina Navratil, Petra Wetzel and Nadja Urbanowitsch for performing MMSE examinations. Last but not least we thank Laura Minnich, English native speaker, for language revision.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

This study obtained an ethical approval by the local review board of the University of Heidelberg. All participants included in this study (or their legal guardians) gave informed consent. All study procedures were performed in accordance to the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. This study was supported financially by the Ministry of Social Affairs, Baden-Württemberg, Germany.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no potential conflicts of interest concerning this research.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zenthöfer, A., Baumgart, D., Cabrera, T. et al. Poor dental hygiene and periodontal health in nursing home residents with dementia: an observational study. Odontology 105, 208–213 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10266-016-0246-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10266-016-0246-5