Abstract

This study explores the nexus between tourism and economic growth in countries bordering the Mediterranean Sea while controlling for foreign direct investment and domestic credits as additional variables within a multivariate panel framework. Empirical evidence is based on annual data from 1995 to 2016 for a panel of 14 selected countries around the Mediterranean Sea region. The findings from the bootstrap panel cointegration test proposed by Westerlund (2007) confirm the long-run equilibrium relationship among the variables under inspection. Subsequently, the Panel Pooled Mean Group Autoregressive Distributed model (PMG-ARDL) estimations suggest positively significant relationships between tourism and economic growth both in short-term, and long-term periods. Thus, this study joins the group of studies that lend support to the tourism-led growth hypothesis. This result was further substantiated by the results of the Dumitrescu and Hurlin (2012) causality analysis, as feedback causality was observed between tourism and economic growth, while unidirectional causality was seen from foreign direct investment to economic growth. That is in support of the foreign direct investment-driven economic growth hypothesis. Strikingly, no causal relationship was observed between domestic credits and economic growth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

International tourism is one of the leading service sectors around the world, which contributes to the wealth of nations not only out of income level but also out of the culture brought from the other countries. Available studies extensively confirm that tourism is a significant source of income, which contributes to the wealth of nations and closure of economic and financial deficits such as current account deficits and balance of payment deficits (Katircioglu et al. 2018). Previous studies find that tourism significantly impacts on economic agents as well, such as financial and energy markets (Katircioglu et al. 2019, 2018). Tourism growth would mean expansion in financial services and finance-related activities, as also argued by Katircioglu et al. (2018). Thus, it can be easily argued that tourism growth or tourism revenues and financial systems are interrelated.

Capital, infrastructure, and knowledge of global marketing, as well as tourism marketing, are the essential factors for development in the tourism sector; this is where foreign direct investment (FDI) comes in. Therefore, tourism and FDI are also interrelated since tourism grows because of FDI as well (Katircioglu 2011). The availability of FDI in an economy can serve as an essential means in developing the tourism sector since it can supply the financial source required to provide better infrastructure, technology, and knowledge. Increased FDI thus contributes positively to tourism development and eventually to economic growth (Contractor and Kundu 1998; Dunning and McQueen 1981; Kundu and Contractor 1999; Sanford and Dong 2000; Tisdell and Wen 1991). Although FDI is a vital tool in tourism development, it was widely ignored in the literature for many years (Dwyer and Forsyth 1994). The relationship between FDI and the tourism sector has been empirically studied in some recent studies (Fereidouni and Al-mulali 2014; Selvanathan et al. 2012; Katircioglu 2011). For example, in a study, Katircioglu (2011) finds that tourism is a catalyst for FDI growth in the case of Turkey, which is justified by the fact that Turkey is a significant tourist destination country in the world and continues to attract significant FDI every year.

The role of the financial sector in the economies has also been well-documented in the literature since Patrick (1966) who proposed two hypotheses exploring the link between financial development and economic growth: (1) the supply-leading hypothesis, denoting that financial development results in economic growth, and (2) the demand-following hypothesis, indicating that economic growth results in financial development. However, results on this link are still mixed with findings and did not reach a consensus yet (Jenkins and Katircioglu 2010). Money supply and domestic credits provided by the banking sector are two popular proxies that are frequently used in the relevant literature (Jenkins and Katircioglu 2010). The financial industry is recently but rarely linked to the tourism sector as well. There are two studies in this field to the best of our knowledge: Ohlan (2017) finds that tourism spurs economic growth via enhancing financial development while Katircioglu et al. (2018) find that tourism and financial markets are in feedback relationship. Thus, the nexus between tourism and financial markets still deserves attention from researchers. In addition to tourism, financial markets are linked to FDI as well. Among rare studies, Gungor et al. (2014) find that FDI and financial markets are interrelated, and they cause economic growth in the case of Turkey. Similar findings have also been reached by Hermes and Lensink (2003), Ang (2009), and Gungor and Katircioglu (2010). However, more research is needed on this nexus as well as similar to the link between tourism and FDI.

Against this backdrop in the relevant literature, this study aims to examine interactions between tourism and growth in a multivariate framework by the incorporation of FDI and domestic credits as a proxy for financial development (Jenkins and Katircioglu 2010) as exogenous variables in the case of the Mediterranean countries. Thus, our research is distinct from previous studies in terms of scope, by being the first (based on the authors’ knowledge) to investigate the theme for selected Mediterranean countries.

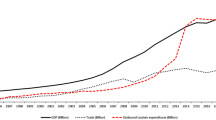

The Mediterranean countries are characterized by special weather conditions and prime coastal areas, which make the region a preferred destination in international tourism. Figure 1 shows the arrivals of non-resident tourists to Mediterranean countries’ borders as of 2016. France, Spain, and Italy have the highest number of tourists among other Mediterranean Sea zone countries.

Provision of clean, safe, and beautiful beaches with high-quality weather and appropriate accommodation is a necessity that may not be sufficiently financed by domestic investors. Since FDI is considered a good source of economic growth in macroeconomics, these Mediterranean countries with good revenue from tourism should plan to attract more FDI, not only to achieve economic growth but also to reduce poverty and unemployment rates (Sodeyfi and Katircioglu 2016; Katircioglu 2009a).

There are several factors that affect a typical investor’s decision about investment in other countries. According to the Eclectic theory, these factors are heavily dependent on the characteristics of the locations and the degree of market internationalization. Place branding is another factor that is not only capable of attracting foreign investment but also able to attract tourism. Place branding thus causes development in the hospitality industry on the one hand and attracts foreign direct investment, thereby linking investors to the tourism sector.

This study thus seeks to contribute to the existing literature by investigating the relationship between FDI, TR, and economic growth while controlling for the contribution of domestic credit in a panel of 14 Mediterranean countries, using up-to-date panel econometric techniques.

The remainder of this study is organized as follows. Section 2 provides a review of related studies; section 3 presents the data and methodology; section 4 discusses the empirical findings. And finally, Section 5 gives the conclusion and possible policy direction.

2 Literature review

The role of tourism in the income growth of countries has been extensively examined in the relevant literature. Some studies confirm the validity of the tourism-led growth hypothesis (Balaguer and Cantavella-Jordá 2002; Gunduz and Hatemi-J 2005; Katircioglu 2011, 2010, 2009b; Etokakpan et al. 2019; Balsalobre-Lorente et al. 2020) while some others do not (Katircioglu 2009c, d). Time series and panel studies reached mixed findings of the role of tourism in growth till the date.

On the other hand, the links of tourism with the segments of economies have also found interest from scholars as well. Katircioglu et al. (2018) set a relationship between tourism and the financial sector in Turkey and see that there exists a long-run link among them; they also find that foreign direct investments and international trade significantly affect this link. Katircioglu et al. (2018) also find that tourism growth in Turkey is mainly influenced by financial markets, but a feedback relationship has also been confirmed by the authors in the study. Ohlan (2017), on the other hand, studies on a similar link and find that tourism growth results in economic growth via financial markets. This finding shows that financial markets and FDI enhance better tourism, which leads to economic growth in the long-term period. Although one way to develop the tourism sector in many countries is through FDI, the dynamic effects of FDI have not received much attention to the date. Katircioglu (2011) finds that tourism and FDI are significantly interrelated, and growth in tourism attracts more FDI in the case of Turkey. However, some other studies find this link in opposite directing revealing that FDI growth results in tourism growth (Bull 1990; Forsyth and Dwyer 1992; Purcell and Nicholas 2001) arguing that as FDI increases job opportunities, facilitates skills and knowledge transfer, improves technology and enhances management quality in the tourism sector. Foreign brands have a positive impact on a location’s image; they also generate more trust and stability (UNCTAD 2008). Peric and Radic (2010) also state that the infrastructures of countries such as airports and hotels are improved by FDI.

Furthermore, in contrast, some scholars focus on and find adverse effects of FDI on economic growth (Clancy 1999; Freitag 1994; Oppermann 1993; Thompson et al. 1995). According to Copeland (1991), too much FDI inflow may raise the level of risk exposure in a recipient country. Also, Brohman (1996) points out that development in the tourism sector through FDI translates into challenges for many developing countries and increases inequality. Barrowclough (2007) finds that the main focus of FDI in the hospitality industry is accommodation. Based on the eclectic theory developed by Dunning (1979), Dunning and Mcqueen (1981) explore the role of transnational corporations in the hotel industry and find that stability of the host country in terms of economic condition and politics are primary factors that attract FDI.

In the relevant literature, studies generally find a significant link between the FDI source and the origin of the tourist who visits the host country (Buckley and Geyikdagi 1996; Snyman and Saayman 2009; Tang et al. 2007). Some studies pay attention to the reasons why some countries attract more FDI than others; for example, some international agreements such as General Agreement on Trade in Services plays an important role (Dunlop 2003; Lee et al. 2002; Te Velde and Nair 2006). On the other hand, Jarvis and Kallas (2008) argue that the European Union members attract FDI more than non-member countries. Some of the factors that cause some states to receive less FDI than others include tax policies, exchange rate fluctuations, high inflation rates, and burdensome bureaucracy (Go et al. 1990; Te Velde and Nair 2006; Zhao and Olsen 1997).

Finally, Tang et al. (2007) investigate the causal relationship between foreign direct investment and tourism in China and find unidirectional causality running from FDI to tourism. Craigwell and Moore (2008) apply panel causality methods on data from Small Island Developing States and find a bidirectional causal relationship between FDI and tourism. Rajapakse (2016) finds a similar result for Sri Lanka. Khoshnevis Yazdi et al. (2017a) confirm bidirectional short-run causality between FDI and tourism while Khoshnevis Yazdi et al. (2017b) do not find any causal relationship between the two.

3 Data and methodology

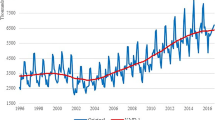

Annual data from 1995 to 2016 are employed for econometric analysis to investigate the causal interactions among economic growth, tourism, foreign direct investment, and domestic credit. For the list of sampled 14 Mediterranean countries, see the appendix section. The data was sourced from the World Bank development indicators (https://data.worldbank.org/indicator). A detailed description of the series used in this study are provided in Table 1:

The empirical route followed in this study is in four steps; (i) Test for cross-sectional dependence. This strategy is necessary to establish whether a common shock effect exists. (ii) Stationarity test among the variables of interest over the sampled period with Pesaran (2007) estimator. (iii) Test for long-run (cointegration) equilibrium relationship via the Westerlund (2007) cointegration test with bootstrapping. (iv) Finally, the Dumitrescu and Hurlin (2012) approach is used to determine causal flows among the variables under review.

3.1 Model specification

This study validates the previously mentioned hypothesis with the econometric model,

From eq. (1) i = 1, 2,.….N while t = 1,2,….T and β0 is the constant term while β1, β2, and β3 are unknown elasticity coefficients of the regressors and εitis the stochastic error term.

3.2 Cross-sectional dependency

Panel data are usually plagued with a common shock effect. This is popularly known as a cross-sectional dependency (CSD). The CSD phenomenon implies the existence of a common effect among the cross-sectional dimensions of the data series (see Breusch and Pagan 1980; Pesaran 2007). The modeling of CSD on the fitted regression helps to avoid spurious regression trap and wrong inference by extension. The Lagrange multiplier (LM) test proposed by Breusch and Pagan (1980) is a commonly used to test for CSD,

The statistics in the CDLM test are asymptotically distributed as χ2 (chi-square) with N(N − 1)/2 degrees of freedom, where N is the number of observations.

3.3 Panel unit root test (PURT)

Panel unit root testing procedures consider both the time-series and the cross-sectional dimensions of the data. The panel unit root test is reputed to be more efficient than conventional time-series approaches, which only consider the time dimension (see Baltagi 2008). This is because of the strength panel data derives from both the time and cross-sectional dimensions with increased variability and less collinearity. However, knowing that CSD usually plagues macro panel data, the need for second-generation panel unit root tests becomes necessary (Maddala and Wu 1999; Pesaran 2007). The second-generation panel unit root tests accommodate CSD and produce asymptotically robust estimates that are not spurious. This study, therefore, employs the second-generation panel unit root tests that are resilient to cross-sectional dependence and heterogeneity. The Cross-sectionally Augmented Dickey-Fuller (CADF) (Pesaran 2007) and Cross-sectional augmented Im, Pesaran, and Shin (2007) (CIPS) panel unit root tests were both applied, given their abilities to provide reliable, robust and consistent results in the presence of CSD and heterogeneity.

3.4 Panel cointegration test (PCT)

The use of a panel cointegration approach in exploring the interaction among series for long-run equilibrium relationships has gained popularity in the empirical literature, given that most economical/finance hypotheses and postulates are long-run based. However, despite the apparent, several studies have failed to affirm cointegration. The reason underpinning the above is that time series and panel data estimation procedures require that the estimated parameters be of the same order of integration either as I(0) or I(1). This shortfall, which is a limitation, was rectified by the newly developed Westerlund (2007) cointegration approach that advances four cointegration estimators to fix the shortcoming and as such gives more reliable and robust estimates. The merits of the newly developed technique are that the test is based on structural dynamics as against other previous cointegration tests that are residual-based. Thus, it does not impose common factor restrictions.

The rationale of this procedure is to analyze the null of no cointegration and the assumption that the error correction term (ECT) in a conditional panel is equal to zero. The first two tests (Ga and Gt) were proposed to allow the alternative hypothesis that the whole panel blocs are co-integrated. However, the Pa and Pt tests were also advanced to test against the alternative hypothesis that at least one cointegrating vector is available. The model specification is given as:

Here, β0i the adjustment to equilibrium path (error term). It is worthy to note that, the penultimate term includes leads and lags of Δx, otherwise we assume exogeneity of x.

The present study adopts the dynamic pooled mean group ARDL methodology as developed by Pesaran et al. (1999) to estimate the magnitude of the long-run (cointegration) coefficient among variables. The technique is applicable in the presence of a mixed order of integration among variables. Also, the choice of the method is informed by its ease of computation as well as its ability to generate reliable and consistent estimates in small samples.

3.5 Panel granger causality (PGC)

This study uses a heterogeneous non-causality panel test advanced by Dumitrescu and Hurlin (2012) to investigate causal interaction between the variables under review. The Dumitrescu and Hurlin (DH) tests are suitable where the cross-sectional dimensions are growing while the time dimension is non-stochastic. The analysis also thrives where T > N, where T represents time, and N stands for the number of observations. The DH test is built on the VAR framework and assumes the absence of CSD. Monte Carlo simulations reveal that the DH test still generates valid estimates even in the presence of CSD. The analysis also shows resilience in applications in both heterogeneous and balanced panels. Furthermore, the DH test displays two distinct features in its distribution, namely asymptotic and semi-asymptotic. The asymptotic is applicable where T > N while semi-asymptotic when N > T. In the presence of CSD, the critical values from asymptotic distribution are used. The linear form of the model specification is as follows:

Where k represents the lag length, \( {\gamma}_i^{(k)} \)are the autoregressive parameter term while \( {\beta}_i^{(k)} \)denotes the regression coefficients that vary within the groups.

The homogenous non-stationary (HNC) null hypothesis against an alternative hypothesis is rendered as:

H0 : βi = 0 ∀i = 1, . . …N.

H1 : βi = 0 ∀i = 1, . . …N1

βi ≠ 0 ∀i = N1 + 1, N1 + 2, . …N

where N1 is unknown, but it satisfies the condition 0 ≤ N1/N ≺ 1. However, the ratio N1/N is required to be inevitably inferior to 1. This implies no causal relationship for any of the countries in the panel. Thus, we fail to reject the null hypothesis of HNC. On the other hand, when H1: βi ≠ 0, ∀i = 1, ……. N, this depicts causal relationship for the entire individuals in the panel.

The causal relationship models are given as:

Here, we assume that lag orders K are identical for all cross-section units of the blocs, and the panel is balanced. For this study, K denoted parsimonious lag length as chosen Akaike Information Criteria.

4 Findings and discussion

We start by analyzing the summary statistics of the variables under consideration. Afterward, we analyze the Pearson correlation test results (See Table 3).

The descriptive statistics are reported in Table 2. We observe that France has the highest average value, while Albania has the lowest average value relative to other countries sampled in the region. Regarding tourism receipts, France and Spain are ranked topmost compared to other countries.

Correlation coefficients are presented in Table 3. We observe a positive and significant relationship between all the variables under consideration. For instance, a positive and significant relationship is observed between real GDP and tourism. This finding validates the tourism-economic growth synergy. A similar trend is seen between FDI and tourism. Although a correlation relationship gives a glimpse of what sort of relationship exists among variables, there is a need to substantiate with more consistent and robust econometric tests to validate the results from the correlation analysis.

Ascertaining a common shock among the cross-sectional dimension of the dataset is necessary to avoid the spurious assumption of cross-sectional independence. To circumvent this problem, we conduct a cross-sectional dependency test. Our study estimates the Pesaran (2007) cross-sectional dependency test which confirms cross-sectional dependency, given the rejection of the null hypothesis of cross-sectional independence for all variables under review.Footnote 1

We also investigate the stationarity properties of the variables with the CIPS and CADF unit root tests. In Table 5, both tests are consistent and give reliable results in the presence of cross-sectional dependence and heterogeneity. CIPS reports that all variables, except tourism, are the first-difference stationary. The CADF test results also show that except domestic credit, all other variables are the first-difference stationary at the 1% significance level; that is, all variables are I (1).

Next, we estimate for long-run equilibrium (cointegration) relationship among the variables. The relatively recent Westerlund (2007) panel cointegration test is estimated with 10,000 iterations, as reported in Table 6. We observe the fragile presence of cointegration. Cointegration is seen only at the whole panel basis and no support of cointegration at each cross-sectional base.

The dynamic long-run and short-run analyses are presented in Table 7. The panel ARDL estimation is robust with a speed of adjustment towards the long-run equilibrium path of 18% (error correction term) convergence with the contribution of the regressor (tourism, foreign direct investment, and domestic credit) on an annual basis. This study offers empirical support to the tourism-led growth hypothesis in both the long and short run. In the long term, we observe that a 1% increase in tourism translates into a 0.10% increase in the real output of the Mediterranean countries. A similar trend is observed in the short run. This finding is in line with the recent studies of Roudi et al. (2018). Our research also shows that in both the short- and long- run; a statistically positive and significant relationship exists between FDI and real GDP in the Mediterranean countries as a 1% increase in FDI leads to a rise in economic growth by 0.004% and 0.04% in the short- and long-run respectively. This finding implies that FDI exerts positively significant effects on real income growth; thus, the government officials of the sampled region are encouraged to attract more FDI, especially in terms of tourism to boost economic growth.

Regarding the impact of domestic credit on economic growth, our study shows a negative and statistically significant impact on economic growth. The plausible reason could be attributed to the weak financial institutions and the effect of the global financial crises in late 2008 and early 2009 as a result of the crash of the Lehman Brothers. By and large, there is a need to strengthen the financial institutions for the investigated region to attract more FDI in the tourism sector, which in the long-run translates into national prosperity.

Finally, Dumitrescu and Hurlin (2012) Granger causality test is employed to probe causal relationships among the variables. As reported in Table 8, we observe a bi-directional causality between tourism and economic growth, thus validating the tourism-induced growth hypothesis and vice versa for economic growth-inducing tourism attraction for the Mediterranean countries. This finding reveals that changes in tourism volume will precede significant changes in real income volume in the Mediterranean countries. On the other hand, causality results show that growth in real income will also precede significant changes in tourism volume (via investments and demand created). This conclusion is insightful as most countries in the bloc investigated are rated as top tourism destinations by the United National World Trade Organization (UNWTO 2018) recent bulletin. For example, France is the leading tourism destination, followed by Spain. Previous empirical studies such as Sokhanvar et al. (2018) also lend support to the outcome of our research. This revelation is quite useful to the bloc of countries within the region as more pragmatic steps can be taken to sustain development.

Similarly, one-way causality is seen running from FDI to real output, as also seen in the study of Tang et al. (2007) in China over the investigated period. This conclusion corroborates the FDI-induced growth hypothesis. The same trend of unidirectional causality from FDI to tourism is found in the study of Rajapakse (2016) in Sri Lanka.

Our study did not find support for causal interaction from domestic credit to real GDP in either way. The same neutrality hypothesis is observed from domestic credit to tourism and domestic credit to FDI.

5 Conclusion and policy implications

Despite the vast development in tourism and the hospitality industry by most developed and developing economies, few studies have examined the effect of FDI on tourism. The originality of this study lies in its use of a sample of Mediterranean countries over the period 1995–2016 within a balanced panel framework while incorporating domestic credit into the econometric framework. Our study leverages recent panel estimators that account for cross-sectional dependence and heterogeneity, which previous studies fail to address but which is necessary to enhance robust coefficients and reliable results for onward policy construction(s).

The CIPS and CADF panel unit root test results confirm that all the investigated variables have a mixed order of integration. Thus, the Panel PMG-ARDL was used to ascertain the magnitude of long and short-run effects. The results suggest a positive and statistically significant relationship between tourism and economic growth; that is, tourism drives economic growth in the Mediterranean countries.

This study gives credence to the tourism-led growth hypothesis as supported in a study of India by Selvanathan et al. (2012), a survey of emerging market economies by Sokhanvar et al. (2018), and a survey of a panel of Small Islands by Alola and Alola (2018), Craigwell and Moore (2008), and Roudi et al. (2018). Thus, tourism is seen as a critical determinant of economic growth for the various economies.

Results show that FDI is vital in the development of the tourism sector in the selected countries; therefore, policymakers need to encourage FDI in their countries. Such an attempt can be possible by several strategies, which will also result in attracting quality FDI. Among such policy might be (1) creating value-adding job opportunities in the tourism sector, (2) enhancing skill base of the tourism industry, (3) facilitating technology transfer, knowledge, and know-how in the tourism sector, (4) increasing competitiveness of tourism firms, and (5) enabling tourism firms to international markets, (5) achieving corporate social responsibility in the tourism sector, and (5) providing environment-friendly investment climate for foreigners.

Our study also corroborates the FDI-led growth hypothesis, with the one-way causality, found running from FDI to tourism and economic growth. This finding implies that FDI and tourism are critical to the economic prosperity of the investigated countries. However, no causal relationship was observed between domestic credit and economic growth and also tourism. This finding is insightful as it depicts the failed financial sector in the sampled region. Government officials in the area are therefore advised to take pragmatic steps to strengthen their various economic sectors, given the global financial distress and interconnectedness of most economies around the globe. Since shocks in one region can have a ripple effect in the other areas, government administrators are required to strengthen their institutions as a means of insulating their economies from externalities emanating out of different regions. Furthermore, as a direction for further inquiry, other scholars could investigate tourism, FDI economic growth nexus by incorporate other macro-economic variables. Besides, the need to model asymmetry is vital as most macro-economic variables exhibit non-linear relationships.

Notes

The results of Pesaran CSD normal, Breusch and Pesaran all corroborate with the Pesaran (2007) CSD results. See Appendix for details.

References

Alola AA, Alola UV (2018) Agricultural land usage and tourism impact on renewable energy consumption among coastline Mediterranean countries. Ener Environ:1–17

Ang JB (2009) Financial development and the FDI-growth nexus: the Malaysian experience. Appl Econ 41(13):1595–1601. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036840701222553

Balsalobre-Lorente, D., Driha, O. M., Bekun, F. V., & Adedoyin, F. F. (2020). The asymmetric impact of air transport on economic growth in Spain: fresh evidence from the tourism-led growth hypothesis. Current issues in tourism, 1-17

Balaguer J, Cantavella-Jordá M (2002) Tourism as a long-run economic growth factor: the Spanish case. Appl Econ 34(7):877–884

Baltagi B (2008) Econometric analysis of panel data. John Wiley & Sons

Barrowclough D (2007) Foreign investment in tourism and Small Island developing states. Tour Econ 13(4):615–638

Breusch TS, Pagan AR (1980) The Lagrange multiplier test and its applications to model specification in econometrics. Rev Econ Stud 47(1):239–253

Brohman J (1996) New directions in tourism for third world development. Ann Tour Res 23(1):48–70

Buckley, P., & Geyikdagi, N. V. (1996). Explaining foreign direct investment in Turkey’s tourism industry. Retrieved from http://www.unctad.org/en/docs/iteiitv5n3a5_en.pdf

Bull A (1990) Australian tourism: effects of foreign investment. Tour Manag 11(4):325–331

Clancy MJ (1999) Tourism and development evidence from Mexico. Ann Tour Res 26(1):1–20

Contractor, F. J., & Kundu, S. K. (1998). Franchising versus company-run operations: modal choice in the global hotel sector. J Int Marketing, 28-53

Copeland, B. R. (1991). Tourism, welfare and de-industrialization in a small open economy. Economica, 58(232), 515–529. Dimension east and southern Africa. New York, NY: author

Craigwell R, Moore W (2008) Foreign direct investment and tourism in SIDS: evidence from panel causality tests. Tour Anal 13(4):427–432

Dumitrescu EI, Hurlin C (2012) Testing for granger non-causality in heterogeneous panels. Econ Model 29(4):1450–1460

Dunning J (1979) Toward an eclectic theory of international production: some empirical tests. J Int Bus Stud 11(1):9–31

Dunlop, A. (2003). Tourism services negotiation issues: Implications for CARIFORUM countries.Report for the Caribbean Regional Negotiating Machinery, mimeo

Dunning JH, McQueen M (1981) The eclectic theory of international production: a case study of the international hotel industry. Manag Decis Econ 2(4):197–210

Dwyer L, Forsyth P (1994) Foreign tourism investment: motivation and impact. Ann Tour Res 21(3):512–537

Etokakpan MU, Bekun FV, Abubakar AM (2019) Examining the tourism-led growth hypothesis, agricultural-led growth hypothesis and economic growth in top agricultural producing economies. Eur J Tourism Res 21:132–137

Forsyth, P., & Dwyer, L. (1992). Impacts of foreign investment in Australian tourism (Occasional Paper No. 10). Canberra: Bureau of Tourism Research

Freitag TG (1994) Enclave tourism development for which the benefits roll? Ann Tour Res 21(3):538–554

Fereidouni HG, Al-mulali U (2014) The interaction between tourism and FDI in real estate in OECD countries. Curr Issue Tour 17(2):105–113

Go F, Pyo SS, Uysal M, Mihalik BJ (1990) Decision criteria for transnational hotel expansion.Tourism. Management 11(4):297–304

Gunduz L, Hatemi-J A (2005) Is the tourism-led growth hypothesis valid for Turkey? Appl Econ Lett 12:499–504

Gungor H, Katircioglu ST, Mercan M (2014) Revisiting the nexus between financial development, FDI, and growth: new evidence from second generation econometric procedures in the Turkish context. Acta Oeconomica 64(1):73–89

Gungor H, Katircioglu S (2010) Financial development, FDI and real income growth in Turkey: an empirical investigation from the bounds tests and causality analysis. Actual Prob Econ 11(114):215–225

Hermes N, Lensink R (2003) Foreign direct investment, financial development and economic growth. J Dev Stud 40(1):142–163

Jarvis J, Kallas P (2008) Estonian tourism and the accession effect: the impact of European Union membership on the contemporary development patterns of the Estonian tourism industry. Tour Geogr 10(4):474–494

Jenkins HP, Katircioglu S (2010) The bounds test approach for Cointegration and causality between financial development, international trade and economic growth: the case of Cyprus. Appl Econ 42(13):1699–1707

Katircioglu, S., Katircioglu, S., & Cizreliogullari, M. N. (2019), Estimating the role of climate changes on international tourist flows: evidence from Mediterranean Island states, environmental science and pollution research (in press, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-04750-w)

Katircioglu S, Katircioglu ST, Altinay M (2018) Interactions between tourism development and financial development. Serv Ind J 38(9–10):519–542

Katircioglu, S. (2011), The bounds test to the level relationship and causality between foreign direct investment and international tourism: the case of Turkey, E & M Ekonomie and management (economics and management), XIV (1): 6–13

Katircioglu S (2010) International tourism, higher education, and economic growth: the case of North Cyprus. World Econ 33(12):1955–1972

Katircioglu S (2009a) Foreign direct investment and economic growth in Turkey: an empirical investigation by the bounds test for co-integration and causality tests. Econ Res - Ekonomska Istraživanja 22(3):1–8

Katircioglu S (2009b) Testing the tourism-led growth hypothesis: the case of Malta. Acta Oeconomica 59(3):331–343

Katircioglu S (2009c) Trade, tourism, and growth: the case of Cyprus. Appl Econ 41(21):2741–2750

Katircioglu S (2009d) Revisiting the tourism-led-growth hypothesis for Turkey using the bounds test and Johansen approach for Cointegration. Tour Manag 30(1):17–20

Khoshnevis Yazdi S, Homa Salehi K, Soheilzad M (2017a) The relationship between tourism, foreign direct investment and economic growth: evidence from Iran. Curr Issue Tour 20(1):15–26

Khoshnevis Yazdi S, Nateghian N, Sheikh Rezaie N (2017b) The causality relationships between tourism development and foreign direct investment: an empirical study in EU countries. J Policy Res Tourism Leisure Events 9(3):247–263

Kundu SK, Contractor FJ (1999) Country location choices of service multinationals: an empirical study of the international hotel sector. J Int Manag 5(4):299–317

Lee M, Fayed HANNA, Fletcher JOHN (2002) GATS and tourism. Tour Anal 7(2):125–137

Maddala GS, Wu S (1999) A comparative study of unit root tests with panel data and a new simple test. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 61(S1):631–652

Ohlan R (2017) The relationship between tourism, financial development and economic growth in India. Future Business J 3:9–22

Oppermann M (1993) Tourism space in developing countries. Ann Tour Res 20(3):535–556

Peric, J., & Radic, M. N. (2010). Impact of foreign direct investment in tourism on economic growth in developing countries. Tourism & Hospitality Management. Retrieved from http://connection.Ebscohost.Com/c/articles/53067112/impact-foreign-direct-investment-tourism-economicgrowth-developing-countries

Pesaran MH (2007) A simple panel unit root test in the presence of cross-section dependence. J Appl Econ 22(2):265–312

Pesaran MH, Shin Y, Smith RP (1999) Pooled mean group estimation of dynamic heterogeneous panels. J Am Stat Assoc 94(446):621–634

Purcell W, Nicholas S (2001) Japanese tourism investment in Australia: entry choice, parent control and management practice. Tour Manag 22(3):245–257

Rajapakse RPCR (2016) The relationship between foreign direct investment and tourism development: evidence from Sri Lanka. Int J Res Econ Social Sci 6(5):183–193

Roudi, S., Arasli, H., & Akadiri, S. S. (2018). New insights into an old issue–examining the influence of tourism on economic growth: evidence from selected small island developing states. Current Issues in Tourism, 1-21

Sanford DM, Dong H (2000) Investment in familiar territory: tourism and new foreign direct investment. Tour Econ 6(3):205–219

Selvanathan S, Selvanathan EA, Viswanathan B (2012) Causality between foreign direct investment and tourism: empirical evidence from India. Tour Anal 17(1):91–98

Snyman JA, Saayman M (2009) Key factors influencing foreign direct investment in the tourism industry in South Africa. Tour Rev 64(3):49–58

Sodeyfi S, Katircioglu S (2016) Interactions between business conditions, economic growth, and crude oil prices. Econ Res - Ekonomska Istraživanja 29(1):980–990

Sokhanvar A, Çiftçioğlu S, Javid E (2018) Another look at tourism-economic development nexus. Tour Manag Perspect 26:97–106

Tang S, Selvanathan EA, Selvanathan S (2007) The relationship between foreign direct investment and tourism: empirical evidence from China. Tour Econ 13(1):25–39

Te Velde DW, Nair S (2006) Foreign direct investment, services trade negotiations and development:the case of tourism in the Caribbean. Dev Policy Rev 24(4):437–454

Thompson C, O’Hare G, Evans K (1995) Tourism in the Gambia: problems and proposals. Tour Manag 16(8):571–581

Tisdell C, Wen J (1991) Investment in China's tourism industry: its scale, nature, and policy issues. China Econ Rev 2(2):175–193

United National World Trade Organization (2018). Please visit publications.unwto.org for more information. Accessed 27-07-2018

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. (2008). FDI and tourism: The development

Westerlund J (2007) Testing for error correction in panel data. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 69(6):709–748

Zhao JL, Olsen MD (1997) The antecedent factors influencing entry mode choices of multinational lodging firms. Int J Hosp Manag 16(1):79–98

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

About this article

Cite this article

Tecel, A., Katircioğlu, S., Taheri, E. et al. Causal interactions among tourism, foreign direct investment, domestic credits, and economic growth: evidence from selected Mediterranean countries. Port Econ J 19, 195–212 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10258-020-00181-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10258-020-00181-5