Abstract

Multiple methods were used to examine the academic motivation and cultural identity of a sample of college undergraduates. The children of immigrant parents (CIPs, n = 52) and the children of non-immigrant parents (non-CIPs, n = 42) completed surveys assessing core cultural identity, valuing of cultural accomplishments, academic self-concept, valuing of academics, and feelings of belonging at the university. Survey results revealed that CIP's placed a greater emphasis on their cultural identity than non-CIPs. In addition, core cultural identity was associated with all three of the motivation scales for CIPs, but only with valuing of academics for the non-CIPs. Implicit association tests revealed that CIPs and non-CIPs both associated success with Caucasians more strongly than with Hispanics, a result that was true even for the Hispanic participants in the study. Finally, a sub-group of 11 CIPs were interviewed to gain additional insights regarding the association between cultural identity and academic motivation. The influence of the multiple contexts in which CIPs operate is used to interpret these results.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The fastest-growing segment of the public school population in the USA and Europe is children of immigrants (Gogolin 2002). These first- and second-generation students must navigate complex social and academic worlds where at least two cultures intersect: the native culture of their parents and the mainstream culture in the USA. These cultures often differ in important ways including primary language, beliefs, and expectations regarding the level of schooling children should achieve and gender roles. In addition, children of immigrants often have responsibilities that the children of native-US born parents do not (Tseng 2004). The children of immigrants often serve as translators for their parents and represent their parents when the family must interact with officials and institutions who speak English, such as schools and other government agencies.

Although many have acknowledged that educating this population involves challenges (Fuligni and Tseng 1999; Valadez 2008; van der Veen and Meijnen 2001), research on the motivation and achievement of children of immigrants is a rapidly growing field with a number of remaining questions. There is much to be learned about the processes, costs, and benefits of acculturation to the mainstream culture of the host country for academic motivation and achievement. How do adolescents navigate the complex pathway between the family's native culture and the mainstream culture of the host country into which immigrant families move (Arends-Toth and van de Vijver 2009; Phelan et al. 1991)? How might this process differ for families from different native cultures, such as Vietnamese and Latino students in the USA or Turkish, Moroccan, and Surinamese students in the Netherlands? What are some of the strategies that adolescents use to navigate this complex pathway? And how does the acculturation process influence the emerging ethnic identity of the adolescent children of immigrants? In this article, these questions are considered as well as the methodological challenges involved in examining these research questions.

Multiple contexts of development

All adolescents and emerging adults must figure out how to function in the multiple contexts in which they operate, such as with family members at home, in social situations with friends, and with authority figures at school and work (Huynh and Fuligni 2008; Phelan et al. 1991). In addition to these relatively proximal contexts of immediate social interactions, adolescents and emerging adults develop within larger societal contexts that contain information about the norms and expectations for different groups within that society (Bronfenbrenner 1994). For example, in the USA, there are a number of stereotypes about different ethnic groups regarding academic and economic achievement. African American and Latino students are often expected to perform worse in school than Asian American and White students. These stereotypes are reinforced by persistent gaps in academic achievement and income between these different ethnic groups. Similar negative stereotypes about Turkish students in the Netherlands have also been reported (Verkuyten et al. 2001).

The effects of these larger societal stereotypes on the motivation and achievement of first- and second-generation immigrants from different countries are not yet clear. Although the act of immigrating in itself can be considered a hopeful act as immigrants sacrifice relationships and familiarity with the culture in the native country for greater opportunities in the new country, there is evidence that the children of immigrants often struggle to take advantage of these opportunities. Whether children of immigrants choose to assimilate by adopting the values and behaviors of middle-class European Americans, such as aspiring to attend college, or with more disenfranchised groups who have not prospered in the USA, such as lower-income African American and third-generation Latinos, depends on a variety of factors. Some research suggests that the assimilation of immigrants depends in part on the attitudes of the host nation (Gitlin et al. 2003; Padilla 2006; Quiles 1989). When the host nation marginalizes the immigrant group, “downward assimilation” is more likely (Portes and Zhou 1993). Waters (1991) also argued that the lower the social status of the immigrant group in the USA, the greater the likelihood that the children of immigrants would adopt the attitudes of disillusioned groups rather than optimistic and aspiring sub-cultures. Similarly, Gogolin (2002) has argued that immigrants and the children of immigrants in Europe are often marginalized and underserved by their schools in Europe, leading many of these students to disengage from school.

The intersection of ethnic identity and academic motivation

The academic motivation of the children of immigrant parents depends on a number of factors (Urdan 2011). The educational and income level of parents, attitudes of the host society and institutions like school toward the immigrant group, and the academic values and behaviors of peers with whom immigrant students associate are some of these factors. Research has also demonstrated that the attitudes and aspirations of immigrant parents for their children's educational success can affect the motivation and achievement of the children of immigrant parents' parental attitudes and aspirations for their children (van der Veen 2003). The fact that many immigrant parents left their homelands and their friends attests to their aspirations for their children, and many of these immigrant families have cultural capital in the form of helpful contacts on the host country or high career aspirations of their own that help motivate their children to succeed academically (Fernandez-Kelly 2008). Language barriers, uncertainty about how school systems in the host country operate, and cultural differences regarding the perceived role of parents in schools, however, can all serve to limit the involvement of immigrant parents in their children's educational endeavors (Ramirez 2003).

In addition to this complex set of structural and contextual factors, the way that the children of immigrants think about themselves, both as students and members of their ethnic groups, can influence academic motivation and achievement (Urdan 2011; van der Veen and Meijnen 2001). As the children of immigrant parents, these second-generation students must figure out how to negotiate between at least two cultural worlds: the native culture of their parents and the dominant US culture in which these students were raised. Phinney and her colleagues (e.g., Phinney 1990; Phinney et al. 2001) argued that there are different types of bi-cultural identities. These include a near-total affiliation with the parents' native culture, near-complete assimilation with mainstream US culture, comfort switching back and forth between the two cultures, or not feeling connected to either culture.

Because of the complexity of the process of developing a bi-cultural identity and the factors that influence assimilation, it is perhaps not surprising to find that the process of acculturation for immigrants and the children of immigrants produces both benefits and costs. For example, studies consistently find that greater levels of acculturation, as measured by frequency of use of English at home, predicts higher academic achievement (Urdan and Garvey 2004). In addition, when parents are able to help children with their schoolwork, monitor their academic progress, and speak English in the home with their children, the children tend to have higher educational aspirations and perform well in school (Plunkett and Bámaca-Gómez 2003). On the other hand, as the children of immigrants become “Americanized” in their use of language, manner of dress and behavior, and attitudes, there is often a perceived distancing from the family's native culture (Souto-Manning 2007). This distancing can produce higher levels of acculturative stress, leading to conflicts between parents and their native-born children and to higher levels of deviant behavior (Gill et al. 2000). Indeed, some have argued that higher levels of acculturation to the values and norms of the host country, and distancing from the native culture, is a developmental risk factor that can undermine academic motivation and achievement (Coll et al. 2009; Perreira et al. 2010; Suarez-Orozco and Suarez-Orozco 1995).

Although it is difficult to predict how being a child of immigrant parents influences academic motivation and performance, it is clear that the multiple contexts in which these children function contribute to their academic motivation and achievement in a complicated manner. Stereotypes about the child's cultural group, their own feelings about assimilation, acculturative stress with parents, and their success at developing comfortable bi-cultural identities can all contribute to their attitudes about school and their aspirations for higher education. For example, if a student has a strong connection to the native culture and perceives that doing well in school will cause some distancing with his native cultural group, academic aspirations and goals may be undermined. In contrast, if a strong part of one's cultural identity is to make the family proud or promote one's cultural group, academic motivation and performance may be enhanced (Fuligni and Tseng 1999; Gibson 1988). Further complicating matters, the effects of these acculturation and bi-cultural identity issues on academic motivation may operate beneath the level of conscious awareness. In the next section of the paper, implicit attitudes and their effects on motivation are considered.

Non-conscious motives

Motivation researchers have long argued that motivation and behavior are influenced by factors beneath the level of conscious awareness (Schultheiss et al. 2010). From Freud's theory about the role of the id and the superego to the unconscious needs for achievement and affiliation described by McClelland, Atkinson, and their colleagues (cf. McClelland 1985), non-conscious motives have long held a prominent place in theories of motivation. Although most motivation researchers have adopted social-cognitive models in recent decades, self-determination theory persists as an example of a prominent theory of motivation that is based in large part on non-conscious needs (Deci and Ryan 1985; Vansteenkiste et al. 2010).

In addition to needs-based models of motivation, non-conscious processes in the form of implicit associations can influence motivation and behavior. Implicit associations refer to connections that people make between certain stimuli or concepts even when they are not aware that they are making such an association, or that the implicit association is affecting behavior. For example, research has documented that even brief exposure to the color red during achievement situations can inhibit performance (Elliot et al. 2007). Scores of studies have examined implicit associations to assess everything from voting tendencies (Bassili 1995) to stereotype threat (Lee and Ottati 1995) to a variety of different “isms” such as racism (Fazio and Dunton 1997) and agism (Perdue and Gurtman 1990).

Cultural identity involves the belief that one's connection to one's culture is an important component of one's overall self-concept. Research has documented that when students, particularly ethnic minority students, have a strong sense of cultural identity, they tend to have stronger academic motivation and higher educational aspirations (Fuligni et al. 2005). Consequently, efforts to increase or maintain a strong sense of cultural connectedness and pride for ethnic and cultural minority students are generally supported empirically. But it is important to remember that research on the benefits of a strong cultural identity has typically relied on self-report data. Even when students perceive a strong sense of cultural identity, it is possible that societal stereotypes about the abilities of one's cultural group might influence the implicit associations one forms about academic success and one's cultural group. For example, even if a Latino student has a strong connection to, and pride in, his Latino heritage and culture, his implicit association between academic success and Latino culture may have been weakened by stereotypes at the societal level, messages from his peers, and role models in his neighborhood. In turn, this weak implicit association between success and Latino culture may affect his academic motivation and educational aspirations in a manner that is beneath his level of conscious awareness. The purpose of the present study is to examine this possibility by comparing the self-reported and implicit associations between culture and academic motivation among children of immigrant parents and children of non-immigrant parents.

Research questions and hypotheses

The overarching question that guides this research is as follows: When combining self-report data with measures of implicit attitudes about cultural norms of success, what is the picture that emerges about the association between cultural identity and academic motivation for children of immigrant parents (CIPs) and non-CIPs? To answer this question, a combination of conscious and non-conscious (i.e., implicit) measures collected from sample CIPs and non-CIPs were used. The purposes of the present research were to begin examining this research question by developing these measures and to examine their effects among a sample of college students. Using these data, three hypotheses were tested:

-

1.

Cultural identity is a more salient feature of overall self-concept for children of immigrants than for children of non-immigrants. Past research has repeatedly found that the children of immigrant parents tend to have a stronger core cultural identity than do children of native-born parents (e.g., Fuligni et al. 2005).

-

2.

Because cultural identity is a salient part of the overall self-concept of children of immigrants, it will be associated with motivational constructs such as academic self-concept and valuing of academics and with feelings of belonging in school more strongly for the CIPs than for children of non-immigrant parents (non-CIPs).

-

3.

As the children of immigrants become increasingly acculturated to societal norms in the USA, their implicit attitudes about who succeeds and who fails will resemble the attitudes of children of non-immigrants. Because the sample of children of immigrants includes only fluent English speakers who were born in the USA and have been academically successful (they attend a 4-year university with rigorous admissions standards), they have acculturated to the point that their implicit attitudes will not differ from the children of non-immigrants.

Methods

Participants

Survey data were collected from 93 university students enrolled in an introductory psychology course. Of these participants, 52 reported that their mother was an immigrant to the USA, and 41 reported that their mother was born in the USA. The participants with immigrant parents reported that their parents came from 22 different countries with the largest number coming from Mexico (n = 21), the Philippines (n = 5), and Vietnam (n = 3). No other countries had more than two representatives in the sample. Sixty-two percent of the sample was female, and 75% were freshmen, 17% were sophomores, and 8% were juniors. Forty-seven percent of the sample spoke a language other than English with their parents at least some of the time while in high school with 34% speaking a language other than English with their parents at least half of the time. Participants were asked to list all of the ethnic labels that they felt applied to them and then indicate the ethnic label they felt described them best. Nineteen percent chose American as the label that described them best. The largest group was some variation on Latin American (i.e., Mexican, Mexican–American, Hispanic, Hispanic–American, Latino/a, Chicano/a, Guatemalan, or El Salvadoran), which included 23 participants. The next largest group (n = 19) indicated that the label American described them best. No other ethnic label was selected by more than 10% of participants.

Of this sample of 93 participants, 77 (42 CIPs, 35 non-CIPs) completed an Implicit Associations Test (IAT). The percentages of men and women, years in college, language use with parents, and preferred ethnic label in this IAT subsample were virtually identical to the percentages in the full sample of participants who completed the surveys.

Finally, a subsample of 11 CIPs were interviewed. This subsample included one woman with both parents born in France, one woman with both parents born in Columbia, one woman whose father was born in Australia and whose mother was born in the USA, one woman born in Thailand to Cambodian parents who immigrated to the USA when the girl was 5, one woman with both parents born in Vietnam, one man with both parents from India, and five participants (three women, two men) who each had two immigrant parents from Mexico.

Measures

Survey

The surveys were organized into four sections. First, participants were asked to provide demographic information including gender, year in school, birth country for each parent, frequency of English language use with parents and with friends, and the preferred ethnic or cultural label of the participant (e.g., Asian–American, Latino, White, etc.). This method of determining participants' preferred ethnic identity label was developed by Alarcón et al. (2000) and reported in Fuligni et al. (2005). Second, participants were asked about their ethnic identity, including how important their ethnic identity was to their self-concept (Core Ethnic Identity, sample item: “In general, being a member of my ethnic group is an important part of my self-image.”) and how positively they felt about their ethnic group (Value of Ethnic Group, sample item: “I feel good about the people in my ethnic group”). These items were adapted from measures used by Fuligni et al. (2005). In the third section of the survey, participants were asked about academic motivation variables, including academic self-concept, valuing of academics, and feelings of belonging at the university. These measures were adapted from the Patterns of Adaptive Learning Survey (Midgley et al. 1998, 2000). Finally, students were asked about their decision to attend college and how family members and their cultural backgrounds influenced their college application and decision-making process, if at all. Most of the items (importance and valuing of culture, academic motivation) employed a 5-point, Likert-like scale. Individual items were averaged to produce scales. All scales had Cronbach's alpha levels above 0.65.

Implicit associations test

Participants completed a measure of their implicit associations among success and failure for Hispanic and Caucasian ethnic groups. The IAT was created using DirectRT software and administered via computer. In this test, participants were first presented with a series of words, one at a time, and they indicated whether they believed the word represented success or failure by pressing the appropriate key on the keyboard. For example, in the first trial, users were presented with a word in the middle of the screen (e.g., “achieve”) and had to press the letter D if they thought the word represented success or the letter K if they thought the word represented failure. “Success” appeared in the upper left corner of the screen in this trial, and “Failure” appeared in the upper right corner of the screen. Participants were asked to respond to each word presented in the middle of the screen as quickly as they could but making as few errors as possible. The computer recorded reaction time (in milliseconds) and whether the participant correctly classified each word. A set of 20 failure and success words were presented randomly in each trial.

In the second section of the IAT, participants were presented a set of 20 photographs of faces, in random order. Each face was either of a Caucasian person or a Hispanic person, and users had to classify the faces as either Caucasian or Hispanic. Again, reaction time and correctness of each response were recorded.

In the third section of the test, participants were presented with either a word or a picture. They had to indicate whether the word or picture represented Success/Caucasian (paired together) or Failure/Hispanic (paired together). For example, a word was presented in the middle of the screen (e.g., “Loser”), and if the participant thought this word was associated either with Success or Caucasian, she should have hit the “D” key, but if she thought the word represented Failure or Hispanic, she should have hit the K key. Twenty words or pictures were presented in random order over four trials, with two trials pairing Success/Hispanic–Failure/Caucasian and the other two pairing Failure/Hispanic–Success/Caucasian. Reaction time and correctness of classification were recorded.

The goal of the IAT was to determine whether people have stronger associations between success and culture for Caucasian or Hispanic ethnic groups. For example, if people have a stronger association between success and Caucasians than they do for success and Hispanics, it should take them longer to react when Success is paired with Hispanic than it does when Success is paired with Caucasian. Similarly, participants should respond more quickly when Failure is paired with Hispanic than when it is paired with Caucasian if they have an association, conscious or not, between failure and Hispanic ethnic groups (Fazio and Olson 2003).

Interview

After the completion of the survey/IAT portion of the study, CIPs were afforded the opportunity to sign up for an interview session. Eleven participants signed up for the interview sessions which took place between 1 and 4 weeks after the survey/IAT session. The purpose of the interviews was to allow the participants to elaborate on their responses to the survey questions. Specifically, the goal was to gain additional insights regarding how CIPs navigated the boundaries between the two cultural contexts that they operated within: the native context of the family and the Euro-centric context of the university. In addition, the interviews were expected to yield information about how participants viewed their bi-cultural identity and how this affected their academic motivation and sense of belonging at the university.

During the interviews, trained research assistants, sometimes accompanied by the first author, asked participants to comment on their responses to some of the questions on the survey. The researchers had the completed surveys in hand during the interviews and reminded the participants of some of their responses, then asked them to elaborate. For example, participants were asked to talk about where their parents were from, how important it was to their parents that they maintain a connection with their native culture, and how participants felt about their own self-selected ethnic label, and to describe their efforts to find a balance between the native culture of their parents and their identity as citizens, mostly native born, of the USA. These interviews were tape recorded and transcribed. They ranged in length from 20–40 min.

Procedure

Participants entered a small computer lab where they were met by a female research assistant. The research assistant told the participant the general purpose of the study was to examine how participants thought about themselves as students and as members of their respective ethnic groups. Then participants read and signed informed consent forms. Half of the participants completed the survey first then completed the IAT measure. The other half completed the IAT before completing the survey. After completing both measures, participants were asked if they would be willing to be interviewed at a later date. Then participants were given the lead authors name and email address and told to contact him with any questions or to learn the results of the study if they were interested. From the list of participants that indicated they were willing to be interviewed, only CIPs were selected. Those students were contacted and interviewed, either by both authors at the same time or by the second author alone. Each participant completed the survey and IAT measures in one-on-one sessions with the research assistant.

Results

The data were analyzed in three steps. First, the survey data were examined to determine whether the ethnic identity variables (core ethnic identity and valuing of cultural identity) were associated with the academic motivation variables (academic self-concept, valuing of academics, and feelings of belonging at the university). Of particular interest were the associations among these variables and whether they differed for CIPs and non-CIPs. Second, the IAT results were examined to determine whether the reaction times of participants differed when Success was paired with Caucasian compared to when Success was paired with Hispanic. Again, comparisons of the reaction time profiles of CIPs and non-CIPs were of particular interest. Finally, the interviews were transcribed and coded to gain additional insights into the ways the CIPs' bi-cultural identities influenced their sense of ethnic identity and their feelings of comfort and belonging in school and in social groups, both before and since entering the university.

Results from the survey data

The survey data were analyzed in two ways. First, participants were divided into two groups: those who had parents who immigrated to the USA (CIPs) and those who did not (non-CIPs). A series of independent t tests were conducted to determine whether these two groups differed on ethnic identity and academic motivation constructs. The means and t values produced by these analyses are presented in Table 1. The CIPs (M = 3.92, SD = 0.90) had significantly higher average scores on the Core Ethnic Identity scale than did children of non-immigrant parents (M = 3.11, SD = 97; t (91) = 4.20, p < 0.001). There were no significant differences between these two groups on any of the other identity or academic motivation scales.

Next, the bivariate correlations between ethnic identity variables (Core Ethnic Identity and Value of Ethnic Group) with the academic motivation variables (Academic Self-Concept, Valuing of Academics, and Belonging) were examined. These correlations were performed two times, first for the entire sample, then separately for the CIPs and non-CIPs. For the whole sample, the Core Ethnic Identity scale was quite strongly correlated with the Value of Ethnic Group scale (r = 0.48). In the whole-sample analysis, the Core Ethnic Identity scale was significantly correlated with academic self-concept (r = 0.26, p < 0.05), valuing of school (r = 0.36, p < 0.001), and belonging (r = 0.22, p < 0.05). The Valuing of Ethnic Group scale was not correlated with academic self-concept (r = 0.26, ns) but was significantly correlated with valuing of school (r = 0.33, p < 0.001) and with feelings of belonging at the university (r = 0.26, p < 0.05).

The results of the correlation analyses that were conducted separately for the CIPs and the non-CIPs are summarized in Table 2. They reveal a couple of noteworthy findings. First, academic self-concept and feelings of belonging were significantly correlated with Core Ethnic Identity for the CIPs but not for the non-CIPs. Second, the associations between Core Ethnic Identity and valuing of academics were significant for both groups. Valuing of Ethnic Group was significant correlated with academic valuing for the non-CIPs but only reached trend level (i.e., p < 0.10) for the CIP group.

Results for test of implicit associations

As described in the “Methods,” the computer-administered test of implicit attitudes was presented over several trials. For the purposes of this study, the results from the last four trials (out of 10 trials total) were used. In these final four trials, participants were asked to indicate whether a word or picture presented on the computer screen belonged in the Success or Hispanic category or the Failure or Caucasian category (trial 1). In trial 2, these categories were reversed (i.e., Success or Caucasian or Failure or Hispanic). These two patterns were each repeated in trials 3 and 4. So in trials 1 and 3, the Success/Hispanic category is contrasted with the Failure/Caucasian category. In trials 2 and 4, the more stereotypical Success/Caucasian pattern is contrasted with the Failure/Hispanic pattern. Longer reaction times were assumed to indicate cognitively incongruent patterns for participants whereas cognitively congruent associations would be responded to more quickly. Similarly, cognitively incongruent patterns were predicted to produce more classification errors among users.

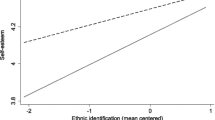

To examine differences in reaction times depending on whether Success was paired with Hispanic or Caucasian, and to examine differences between CIPs and non-CIPs in reaction times, mixed-model repeated-measures ANOVAs with trial (1, 2, 3, and 4) as the within-subjects factor and a 2-factor (CIP vs. non-CIP) between-subjects factor were performed. The average reaction times within each trial are presented in Table 3 and Fig. 1. If the average reaction times were faster in trials 2 and 4 than in trials 1 and 3, this constituted evidence that implicit attitudes about the associations between success and failure for Caucasians and Hispanics differed. Mixed-model repeated-measures ANOVA with a fixed factor to test for differences in the accuracy of classifications by the participants was also conducted.

Comparison of CIPs with non-CIPs

The results of the repeated-measures ANOVAs, including the mean reaction times and percentage of correct classifications for trials 1 through 4, are presented in Table 3. For the tests involving reaction time, a significant repeated-measures linear effect for trial (F = 21.67, p < .001, partial eta-squared = 0.22) and a significant cubic effect (F = 45.62, p < 0.001, partial eta-squared = 0.38) were found. No significant between-subjects effect (F = 1.11, ns), trial × CIP interaction linear effect (F = 1.19, ns), or cubic effect (F = .40, ns) was found. Post hoc analyses revealed that the average reaction times for trials 2 and 4 differed from trials 1 and 3, but not from each other. The average reaction times for trials 1 and 3 also did not differ from each other significantly. These patterns were true within the CIP group, within the non-CIP group, and across both groups combined. There were no significant main effects or interaction effects for the comparisons of percentage of correct classifications. Taken together, these results indicate that both groups, the children of immigrant parents and the children of non-immigrant parents, took longer to correctly classify words and images in the astereotypical pairing of Success or Hispanic and Failure or Caucasian category scheme than they did in the more stereotypical pairing of Success or Caucasian and Failure or Hispanic category.

Interview results

The interview transcripts were analyzed to identify themes that emerged in the interviews. Both authors analyzed a sub-set of four of the interview transcripts to identify themes. The authors discussed the emergent themes of the four interviews until they agreed on which statements in the interviews corresponded to each theme. Next, the second author analyzed the remainder of the interviews. After analyzing all 11 interview transcripts, the second author, in consultation with the lead author, refined the themes to include new topics that emerged in the newly analyzed interviews. The second author then re-analyzed all 11 interview transcripts and met with the lead author to ensure that both authors agreed on the themes that emerged from the interviews and the categorization of the statements in the interviews into the appropriate themes.

This thematic analysis of the interview transcripts revealed three themes regarding the factors that influence CIPs as they attempted to forge cultural identities. First, a distinction emerged between participants according to whether their messages from parents in the family context emphasized maintaining a strong connection to their native culture or placed greater emphasis in the importance of the participants' individual characteristics. Second, participants talked about the role of the particular community context in which they were raised and its influence on their developing cultural identity. Finally, the participants interviewed varied in the degree to which they attempted to balance their cultural identities across multiple contexts. Next, each of these themes is described in more detail.

Parental stress on cultural or personal characteristics

There are differences among those participants whose parents stressed cultural characteristics (e.g., speaking the native language and celebrating traditional holidays) over the development of personal skills and hobbies (e.g., engaging in sports, academics, and clubs). Differences were apparent in eight participants when discussing their experiences of applying to college, how comfortable they were within their schools, and most importantly, the strength of their connection with their personal cultural identity as young adults. Those that had parents that stressed cultural characteristics expressed concerns about having the feeling of selling out and never being able to fully accommodate their parent's expectations. As one participant put it,

“Yeah, they make fun of me and my brother because sometimes we'll be thinking about explaining something and we don't know the word and they'd be like, ‘Oh your forgetting Spanish.’ They get worried, like ‘What? You're Mexican and you don't even know your own language?’”

As this excerpt reveals, some CIPs are confronted with one of the costs of acculturation: a loss of connection to their native culture. Unexpectedly, this cost was less pronounced among participants whose parents did not emphasize maintaining a connection to the family's native culture. Those with parents who emphasized the development of personal characteristics over cultural connections did not talk about concerns of selling out. A participant stated,

“Well, I'll say this: My father, although he has Indian taste in activities and stuff like that, he always kind of wanted me, he didn't say the Jesuit education and stuff like that, but he always wanted me to be healthy academically, spiritually, socially, athletically.”

It is apparent in this quote that the father emphasized his son's personal characteristics. By allowing his son to enroll in a Jesuit institution, a school that does not reflect his own religious beliefs but offers his son good academic opportunities, this participant's father indicated that his son's personal growth was more important to him than enforcing his son's connection to the father's native culture. The participant in this quote indicates that his connection to his cultural background comes secondary to his academic, spirituality, social, and athletic growth.

Some of the participants who had parents that de-emphasized their connection to their native culture talked about their realization, as adolescents and emerging adults, that they lacked a strong connection to their native culture but were also not fully integrated into the dominant Caucasian culture of their high schools and the university, as illustrated by this quote from a participant of Indian descent:

“I don't know if it was a rebellious thing, but I wanted to adopt Western values. But somewhere along the way I remember in high school I went out for the football team while more of the [kids of] Indian descent were on the speech and debate team and stuff. And while it felt good that I transcended this cultural gap my skin color is always going to be brown. I'm never going to be one of the people of Caucasian descent, you know, and so that's when I start to wonder if I should have held on to more of my roots.”

For some, this created a longing to learn more about their native culture, including religious beliefs and languages. For others, the distance from the native cultures of their parents was not mentioned as a concern, and the perceived assimilation into the dominant culture was complete.

The community's influence

Eight of the 11 interview participants spoke about the area where they grew up in contributing to the strength of their cultural connection. This influenced their perception about what it meant to gain higher education and what roles their cultural background had in their academic upbringings. Demographics were also a contributing factor to how the participants felt and adapted to their ethnic role in society. For example, some of the participants noted that the schools and neighborhoods in which they were raised were primarily White and middle class. These participants attended high schools with students who were almost all native speakers of English and with high rates of admission into 4-year colleges and universities. In effect, these participants were surrounded by White, middle-class people and largely assimilated into that culture.

Other interview participants specifically noted the importance of being around members of their own native culture, either in their neighborhoods as they grew up or once they entered the university. Two students, both of Mexican descent, talked about their sense of responsibility to go back to their neighborhoods when they graduated from college to help students of similar cultural backgrounds excel in school and matriculate onto college while maintaining a strong connection to their cultural identity.

Strategies for balancing cultural identities in different contexts

Six of the interview participants discussed strategies they had adopted to help them create a balance between their cultural beliefs and values and mainstream society. One of these strategies involved joining clubs based on cultural heritage, as this participant discussed:

“Well when I was younger like in high school and middle school I really wanted to fit in so I almost disconnected myself from my original culture. But as I got older I grew more appreciative of both cultures. Like I'm in a Vietnamese club here and then its just that I'm around more similar types of people than what I was then what I was in high school and younger.”

A second strategy participants discuss was taking ethnic-specific classes that allowed the participants to gain a deeper understanding of their ethnic backgrounds and learn about other perspectives. For some, these classes provided a fresh perspective about their cultural identity and helped them understand their history, whereas for others, it was a way to connect themselves to their culture and give them the sense of connectedness that they needed to gain in order to feel a part of their cultural community. One participant described the importance of the culturally specific classes as follows:

“Because I was in like Chicano studies and history and things like that. And then I was taking English with other minorities and now I'm not and I feel like I'm kind of slipping away from that because I feel like I kind of see my friends less and stuff like that.”

For this student and others, culturally specific classes provided an opportunity for students who are under-represented in the larger university to feel culturally connected to students of similar cultural backgrounds.

Finally, several students talked about the utility, and the costs, of adopting different cultural identities in different contexts. For example, several students reported behaving in a manner that is consistent with their parents' native culture when they are in the family context but then adopting the dominant culture behaviors and norms in other contexts, such as the university. For some students, this cultural code switching was simply accepted as a part of being a bi-cultural person in the USA, as illustrated by this participant's statement:

“I was in the Latino Unidos club, which hosted Mexican holidays and things like that at school and we would get everyone to participate, but at the same time I was also like in the French Club. I think I found a balance early on in life of like whom I am and not trying to stress too much. I'm Mexican, this is me when I'm not Mexican this is me when I am Mexican.”

For other students, however, this frequent switching back and forth created a sense of identity confusion and disingenuousness, as described by this participant:

“Um, I guess it's pretty different because it is predominantly white in that area (Kansas City) so you kind of just learn to integrate with them and then it's kind of like a double face. Like when you're at home you're like a different person and then when you're at school its different too.”

The process of developing a coherent identity is a challenge for most adolescents and emerging adults. For those with one foot in the native cultural context of their parents and another foot in the dominant White cultural context of the USA, this task of identity integration across these cultural contexts can be particularly challenging, as the interviews with the children of immigrant parents revealed. It is important to note that the subsample of participants in the interview portion of this study were self-selected and therefore may not represent the larger sample or the views of children of immigrant parents in general. With that caution in mind, these interviews offer a preliminary window into some of the concerns that CIPs have as they develop a bi-cultural identity and find their place in a mostly Caucasian university.

Discussion

For children who are members of the majority culture in a country, born to parents who are natives of that country, ethnic identity is rarely a salient feature of one's overall sense of self. For these children, the boundaries between the multiple contexts in which they operate—school, peers, family, and society—tend to be permeable, the transitions between them easy (Phelan et al. 1991). For the children of immigrant parents, however, navigating the often-contradictory norms and expectations of these different contexts can be confusing and challenging. The process of understanding who one is and how one fits into school and society involves all levels of context, from internal processes within the individual (identity) to family and even extending to the larger society. As the children of immigrants try to figure out how much of their native family culture to retain and how much of the mainstream culture in the host country to adopt, they are influenced by the attitudes and behaviors of family members, peers, teachers, and the host society. Forging coherent cultural identities and academic identities requires making sense of these multiple and often-contradictory contextual messages.

Among the many reasons that immigrants move to Europe or the USA, parents regularly state that they hope to provide better educational and financial opportunities for their children than they would have been afforded in their native countries (Fuligni and Tseng 1999). Yet, the children of immigrants often find themselves in the complex and confusing position of developing a personal identity that straddles two cultural contexts: the mainstream culture of the host country and the native culture of the parents. As adolescents and emerging adults try to figure out which elements of each broad cultural context to incorporate into their personal identity, they must develop their own interpretation of what each culture means to them. The purpose of this research was to examine the associations, both conscious and unconscious, that adolescents forge between their cultural identity and their academic identity. In this study, academic identity is operationalized in motivational terms: how students think about their academic abilities (academic self-concept), the importance they attach to their academic work (valuing of academics), and feelings of belonging in school.

The three different methods used to examine the motivation and cultural identity of the sample of college students produced results that were at times consistent and at other times contradictory. All three suggest that cultural identity is a complicated and messy construct, particularly for the children of immigrants. As the self-report surveys and interviews revealed, and previous research has documented, the children of immigrant parents differ in the degree to which they identify with the native culture of their parents, the dominant culture in the USA, both, or neither (Fuligni et al. 2005; Phinney and Ong 2007). The results of the interview portion of the study were particularly enlightening on this issue. Whereas some of the participants in the subsample described early foreclosure and assimilation with the dominant cultural values and norms in the USA, others described experiences in adolescence and emerging adulthood, often in the peer and school contexts, that made them question and adjust their cultural identity. In addition, some participants described a high degree of comfort switching back and forth between their two cultural contexts, whereas others struggled with feelings of incomplete membership in either cultural group. Similar results have been reported by others (e.g., Phelan et al. 1991; Phinney et al. 2001) and again underscore the complexity of cultural identity formation and integration for the children of immigrant parents. How students think about themselves, both in terms of who they are as students and who they are culturally, depends on contextual factors as proximal as their peer and family groups and as distal as the societal messages about the norms of the mainstream cultural values in the host nation and feelings of people in the host nation about the immigrant groups (Gogolin 2002).

Academic motivation and cultural identity

The survey results suggest that cultural identity is an important construct for the children of immigrants. These students say that cultural identity is a core component of their overall identity, and this is associated with their academic self-concept, feelings of belonging in college, and with valuing of academics. In contrast, children of non-immigrants were less likely to report that their cultural identity was a central component of their overall self-concept and had non-significant associations between cultural identity and feelings of belonging in college or academic self-concept. Taken together, these results suggest that cultural identity is important to children of immigrants, but it is not a blanket that covers all aspects of academic motivation and self-concept. Indeed, there were not differences in valuing of academics, feelings of belonging in school, or academic self-concept between children of immigrants and children of non-immigrants, and cultural identity did not correlate with valuing of academics in substantially different ways for these two groups. The survey data suggest that having a strong and positive cultural identity has some motivational benefits and few costs, particularly for the children of immigrant parents. They also support previous findings that identification with the native culture may influence some values more strongly than others as immigrant families become acculturated to the mainstream norms and values of the host country (Arends-Toth and van de Vijver 2009).

In contrast, the results from the test of implicit associations revealed no association between cultural identity and reaction times. The children of immigrants and the children of non-immigrants both took longer to make associations between success and Hispanic than success and Caucasian. In addition, there were no significant correlations between the reaction times and the measures of cultural identity. In other words, regardless of the strength of one's cultural identity or feelings about the value of one's culture, participants appeared to have weaker implicit associations for the pairing of Success–Hispanic than for the pairing of Success–Caucasian. In addition, the association between Failure–Hispanic was stronger than the association between Failure–Caucasian.

Although children of immigrants have positive conscious associations between cultural identity and academic motivation, as narrowly defined in this study, the measure of non-conscious associations reveals no such benefits. One interpretation of these results is that the children of immigrants included in this study had internalized stereotypical messages from the mainstream cultural context that success is more strongly paired with Caucasian than with Hispanic culture. These implicit attitudes may not influence conscious attitudes (as evidenced by the positive associations between the conscious measures of cultural identity and academic motivation for children of immigrants), but they may influence motivation and achievement under certain circumstances, as demonstrated in research on stereotype threat (Steele and Aronson 1995). Students may be less inclined to pursue areas of work or study for which their implicit association between success and their own cultural group is weak.

Limitations and future directions

This study represents an initial attempt to compare the connection between motivation and achievement of the children of immigrant parents and the children of non-immigrant parents using both conscious and implicit measures. Prior research documenting the positive association between cultural identity and motivation was replicated. In addition, the positive association found with self-report data was not replicated with the implicit measures used in this study. Indeed, there was no association between the implicit and self-reported measures of cultural identity.

Although provocative, the impact of these findings are tempered somewhat by the nature of the samples and measures used. The CIP sample was born to parents from several different countries, some with stronger stereotypes about the academic achievement of their cultural groups than others. For example, in the USA, Latinos are typically expected to perform poorly in school, whereas Vietnamese and Indian students are expected to perform well. Members of the sample with parents who immigrated from countries like Australia and France would most likely be indistinguishable from other middle-class White students. Similarly, the sample of CIPs were more academically successful (they attended a 4-year college with rigorous admission standards) and likely came from wealthier families, than the first- and second-generation students that have been examined in other research (e.g., Necochea and Cline 2000; Verkuyten et al. 2001). Although the comparison of CIPs with non-CIPs produced interesting results, future research examining a more homogenous sample of CIPs would likely provide results that were more easily interpreted.

A related limitation involves the IAT measure. In the test of implicit associations, only two cultural groups, Hispanic and Caucasian, were compared. Although Latino students were the largest sub-group in the CIP sample, this sample consisted of participants of several different cultures and ethnicities. Therefore, comparing the IAT results of CIPs and non-CIPs did not produce a clean comparison of two distinct cultural groups. Future research that examines the reaction times of Hispanic students with the reaction times of Caucasian students on this IAT measure would likely prove most interesting. We are currently collecting such data.

Finally, it is worth noting that all of the participants in the samples, both CIPs and non-CIPs, were quite highly acculturated to the dominant US culture. They all attended schools in the US, spoke English from an early age, were successful academically, and matriculated onto a selective 4-year university. It is not clear how the associations between cultural identity and academic motivation, both explicit and implicit, would generalize from this sample to a less-acculturated sample, a less academically successful sample, or a younger sample. We are currently analyzing data collected from Latino high school students in an inner city school to examine these questions.

Conclusion

The intersection between cultural identity and academic motivation is a complex one for the children of immigrant parents, many of whom are struggling to figure out how to integrate the norms and expectations of the two cultural contexts in which they live. Most of the extant research in this area has relied on self-report measures, and this research has often found that academic motivation and performance is enhanced when students have a strong sense of cultural identity. Although the results of the present study support this extant research, it also suggests that implicit attitudes may differ from self-reported attitudes and beliefs. To gain additional insights into the motivation and cultural identity of students, particularly those who have traditionally underperformed in schools in the USA, it may be important to consider both implicit and explicit attitudes.

References

Alarcón, O., Szalacha, L. A., Erkut, S., Fields, J. P., & García Coll, C. (2000). The color of my skin: a measure to assess children's perceptions of their skin color. Applied Developmental Science, 4, 208–221.

Arends-Toth, J., & van de Vijver, F. J. R. (2009). Cultural differences in family marital, and gender values among immigrants and majority members in the Netherlands. International Journal of Psychology, 44, 161–169.

Bassili, J. N. (1995). Response latency and the accessibility of voting intentions: what contributes to accessibility and how it affects vote choice. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 21(7), 686–695.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1994). Ecological models of human development. International encyclopedia of education, (vol. 3) (2nd ed., pp. 1643–1647). Oxford: Elsevier Sciences.

Coll, C. G., Flannery, P., Yang, H., Suarez-Aviles, G., Batchelor, A., & Marks, A. (2009). The immigrant paradox: A review of the literature. Paper presented at the conference: Is becoming American a developmental risk: Children and adolescents from immigrant families. Brown University.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York: Plenum.

Elliot, A. J., Maier, M. A., Moller, A. C., Friedman, R., & Meinhardt, J. (2007). Color and psychological functioning: the effect of red on performance attainment. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 136, 154–168.

Fazio, R. H., & Dunton, B. C. (1997). Categorization by race: the impact of automatic and controlled components of racial prejudice. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 33(5), 451–470.

Fazio, R. H., & Olson, M. A. (2003). Implicit measures in social cognition research: their meaning and use. Annual Review of Psychology, 54, 297–327.

Fernandez-Kelly. (2008). The back pocket map: social class and cultural capital as transferable assets in the advancement of second-generation immigrants. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 620, 116–137.

Fuligni, A. J., & Tseng, V. (1999). Family obligation and the academic motivation of adolescents from immigrant and American-born families. In T. Urdan (Ed.), Advances in Motivation and Achievement, (vol. 11) (pp. 159–183). Stamford: JAI Press.

Fuligni, A. J., Witkow, M., & Garcia, C. (2005). Ethnic identity and the academic adjustement of adolescents from Mexican, Chinese, and European backgrounds. Developmental Psychology, 41, 799–811.

Gibson, M. A. (1988). Accommodation without assimilation: Sikh immigrants in an American high school. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Gill, A. G., Wagner, E. F., & Vega, W. A. (2000). Acculturation, familism, and alcohol use among Latino adolescent males: longitudinal relations. Journal of Community Psychology, 28, 443–456.

Gitlin, A., Buendia, E., Crosland, K., & Doumbia, F. (2003). The production of margin and center: welcoming-unwelcoming of immigrant students. American Educational Research Journal, 40, 91–122.

Gogolin, I. (2002). Linguistic and cultural diversity in Europe: a challenge for educational research and practice. European Educational Research Journal, 1, 123–138.

Huynh, V. W., & Fuligni, A. J. (2008). Ethnic socialization and the academic adjustment of adolescents from Mexican, Chinese, and European backgrounds. Developmental Psychology, 44, 1202–1208.

Lee, Y., & Ottati, V. (1995). Perceived in-group homogeneity as a function of group membership salience and stereotype threat. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 21(6), 610–619.

McClelland, D. C. (1985). How motives, skills, and values determine what people do. American Psychologist, 40, 812–825.

Midgley, C., Kaplan, A., Middleton, M., Maehr, M. L., Urdan, T., Anderman, L. H., et al. (1998). The development and validation of scales assessing students' achievement goal orientations. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 23, 113–131.

Midgley, C., Maehr, M. L., Hruda, L., Anderman, E., Anderman, L., Freeman, K., et al. (2000). Manual for the Patterns of Adaptive Learning Scales. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan.

Necochea, J., & Cline, Z. (2000). Effective educational practices for English language learners within mainstream settings. Race, Ethnicity, and Education, 3, 317–332.

Padilla, A. M. (2006). Bicultural social development. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 28, 467–497.

Perdue, C. W., & Gurtman, M. B. (1990). Evidence for the automaticity of ageism. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 26, 199–216.

Perreira, K. M., Fuligni, A., & Ptochnick, S. (2010). Fitting in: the roles of social acceptance, and discrimination in shaping the academic motivations of Latino youth in the U.S. southeast. Journal of Social Issues, 66, 131–153.

Phelan, P., Davidson, A. L., & Cao, H. T. (1991). Students' multiple worlds: negotiating the boundaries of family, peer, and school cultures. Anthropology and Education quarterly, 22, 224–250.

Phinney, J. (1990). Ethnic identity in adolescents and adults: a review of research. Psychological Bulletin, 108, 499–514.

Phinney, J. S., & Ong, A. D. (2007). Conceptualization and measurement of ethnic identity: current status and future directions. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54, 271–281.

Phinney, J., Romero, I., Nava, M., & Huang, D. (2001). The role of language, parents, and peers in ethnic identity among adolescents in immigrant families. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 30, 135–153.

Plunkett, S. W., & Bámaca-Gómez, M. Y. (2003). The relationship between parenting, acculturation, and adolescent academics in Mexican-origin immigrant families in Los Angeles. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 25, 222–239.

Portes, A., & Zhou, M. (1993). The new second generation: segmented assimilation and its variants among post-1965 immigrant youth. Annals, 530, 74–96.

Quiles, J. A. (1989). The cultural assimilation and identity transformation of Hispanics: A conceptual paradigm. ERIC document 315473.

Ramirez, A. Y. F. (2003). Dismay and disappointment: parental involvement of Latino immigrant parents. The Urban Review, 35, 93–110.

Schultheiss, O. C., Rösch, A. G., Rawolle, M., Kullmann, J., & Kordik, A. (2010). Implicit motives: Current topics and future directions. In T. Urdan and S. Karabenick (Eds.), Advances in Motivation and Achievement, v. 16A: The decade ahead. Castle Hill: Emerald Press.

Souto-Manning, M. (2007). Immigrant families and children (re)develop identities in a new context. Early Childhood Education Journal, 34(6), 399–405.

Steele, C. M., & Aronson, J. (1995). Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African-Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 797–811.

Suarez-Orozco, C., & Suarez-Orozco, M. M. (1995). Transformations: Immigration, family life, and achievement motivation among Latino adolescents. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Tseng, V. (2004). Family interdependence and academic adjustment in college: youth from immigrant and U.S.-born families. Child Development, 75, 966–983.

Urdan, T. (2011). Factors affecting the motivation and achievement of immigrant students. In K. Harris, S. Graham, & T. Urdan (Eds.) APA Educational Psychology Handbook, v. 2. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association, 293–313.

Urdan, T., & Garvey, D. (2004). The education of immigrant and native-born students: Local and national perspectives. In T. Urdan & F. Pajares (Eds.), Educating adolescents: Challenges and strategies (pp. 149–178). Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing. Volume 4 in the Adolescence and Education series.

Valadez, J. R. (2008). Shaping the educational decisions of Mexican immigrant high school students. American Educational Research Journal, 45, 834–860.

van der Veen, I. (2003). Parents' education and their encouragement of successful secondary school students from ethnic minorities in the Netherlands. Social Psychology of Education, 6(3).

van der Veen, I., & Meijnen, G. W. (2001). The individual characteristics, ethnic identity, and cultural orientation of successful secondary school students of Turkish and Moroccan background in the Netherlands. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 30(5), 539–560.

Vansteenkiste, M., Miemiec, C. P., & Soenens, B. (2010). Motivational dynamics within self-determination theory: Trends and future directions. In T. Urdan and S. Karabenick (Eds.), Advances in motivation and achievement, v. 16A: The decade ahead. Castle Hill: Emerald Press.

Verkuyten, M., Thijs, J., & Canatan, K. (2001). Achievement motivation and academic performance among Turkish early and young adolescents in the Netherlands. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs, 127(4), 378–408.

Waters, M. C. (1991). The intersection of race, ethnicity, and class: Second generation West Indians in the United States. Paper presented at the Race, Ethnicity, and Urban Poverty Workshop, Chicago.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Tim Urdan. Department of Psychology, Santa Clara University, 500 El Camino Real Santa Clara, CA 95053. E-mail: turdan@scu.edu

Current themes of research:

Academic motivation. Cultural identity. Acculturation. Adolescent development. Hispanic populations.

Relevant publications:

Urdan, T., Solek, M., & Schoenfelder, E. (2007). Students' perceptions of family influence on their academic motivation: A qualitative analysis. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 22, 7–21.

Urdan, T., & Schoenfelder, E. (2006). Classroom effects on student motivation: Goal structures, social relationships, and competence beliefs. Journal of School Psychology, 44, 331–349.

Urdan, T., & Mestas, M. (2006). The goals behind performance goals. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98, 354–365.

Urdan, T. (2004). Predictors of academic self-handicapping and achievement: Examining achievement goals, classroom goal structures, and culture. Journal of Educational Psychology, 96, 251–264.

Urdan, T. (2004). Using multiple methods to assess students' perceptions of classroom goal structures. European Psychologist, 4, 222–231.

Chantico Munoz. Department of Psychology, Santa Clara University, 500 El Camino Real Santa Clara, CA 95053. E-mail: csmunoz1987@gmail.com

Current themes of research:

Academic motivation. Cultural identity. Acculturation. Adolescent development. Hispanic populations.

Relevant publications:

No relevant publications in the field of psychology of education.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Urdan, T., Munoz, C. Multiple contexts, multiple methods: a study of academic and cultural identity among children of immigrant parents. Eur J Psychol Educ 27, 247–265 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-011-0085-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-011-0085-2