Abstract

Background

Most people prefer to “age in place” and to remain in their homes for as long as possible even in case they require long-term care. While informal care is projected to decrease in Germany, the use of home- and community-based services (HCBS) can be expected to increase in the future. Preference-based data on aspects of HCBS is needed to optimize person-centered care.

Objective

To investigate preferences for home- and community-based long-term care services packages.

Design

Discrete choice experiment conducted in mailed survey.

Setting and participants

Randomly selected sample of the general population aged 45–64 years in Germany (n = 1.209).

Main variables studied

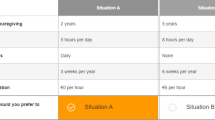

Preferences and marginal willingness to pay (WTP) for HCBS were assessed with respect to five HCBS attributes (with 2–4 levels): care time per day, service level of the HCBS provider, quality of care, number of different caregivers per month, co-payment.

Results

Quality of care was the most important attribute to respondents and small teams of regular caregivers (1–2) were preferred over larger teams. Yet, an extended range of services of the HCBS provider was not preferred over a more narrow range. WTP per hour of HCBS was €8.98.

Conclusions

Our findings on preferences for HCBS in the general population in Germany add to the growing international evidence of preferences for LTC. In light of the great importance of high care quality to respondents, reimbursement for services by HCBS providers could be more strongly linked to the quality of services.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Population aging has become a global phenomenon in recent decades [1]. Germany is among the fastest aging countries in Europe [2], with 21% of the population aged ≥ 65 years in 2014 [3]. By the year 2060, while the total German population is projected to shrink by 10–16%, those aged 60–79 years (≥ 80 years) are expected to grow by 8% (102%), compared to 2013 [4]. This development goes along with many economic and social changes [5, 6], like the delivery and financing of long-term care (LTC) [7, 8]. LTC comprises help/care services that aim to delay functional decline, helping those affected to maintain the highest degree of quality of life [9].

Aiming to provide a comprehensive solution to the growing need for LTC in Germany, the government introduced the mandatory LTC insurance in 1994 [10]. As a part of the social security system, the LTC insurance covers the entire population (LTC beneficiaries). Entitlement is based on “dependency”, i.e., need for help with at least two activities of daily living and one additional instrumental activity of daily living for a period of at least 6 months. Three dependency levels are distinguished based on how often assistance is needed and on how time-consuming care activities are [10]. LTC benefits differ by dependency level and are moreover capped [10], i.e., only part of the assessed need is covered by the LTC insurance [11].

In light of the demographic changes in Germany, the number of LTC insurance claimants (i.e., beneficiaries claiming LTC insurance benefits) has grown from 1.07 million in 1995 to 2.63 million in 2013 [10, 12], and is expected to reach 4.52 million by 2060 [13]. The majority of claimants are ≥ 65 years (83% in 2013) and receive home care (67% in 2013) [12], supported in form of cash benefits (with no regulations on how cash is used) or professional home- and community-based services (HCBS). HCBS are offered by non-profit and for-profit providers; HCBS bills are covered by LTC insurance funds up to the benefit caps [10].

Of the 1.86 million LTC insurance claimants having received home care in 2013, about 1.25 million chose cash benefits (typically passed on to informal caregivers), the remainder of 0.61 million HCBS or a combination of both types. Because of decreases of informal caregivers, the use of HCBS has grown disproportionally by + 36.8% since 1999, compared to + 21.3% for cash benefits (informal care) [12]. Since the mid 2000’s, there have been few changes in the utilization of different LTC benefits and respective services, however [13]. In light of these trends and expected changes in the social structure in Germany [6], an increase in the use of HCBS is expected.

Integrating knowledge on individuals’ preferences into care services is associated with improved quality of care outcomes and overall well-being [14,15,16]. The incorporation of care preferences, therefore, is a core element of person-centered care [17]. The current study investigated preferences for (different aspects of) hypothetical HCBS packages in a randomly selected sample of LTC insurance beneficiaries from the general population, using a discrete choice experiment (DCE) [18, 19]. The study provides evidence on HCBS features most important to LTC insurance beneficiaries in Germany.

Methods

DCE are increasingly used to elicit preferences and willingness to pay for various health- and care-related aspects (e.g., of patients, caregivers, and the general population) [19]. The method allows to determine the relative importance (utility/value) of specified attributes from hypothetically consumed products or services [18]. With regard to LTC, DCE have been used to elicit preferences for HCBS in Australia [20], LTC facilities in Japan [21], LTC insurance in Italy [22], and LTC service aspects in the Netherlands [23].

Attributes and levels

Attributes and levels for HCBS were developed in a step-wise qualitative approach [24]. First, we conducted sequential literature searches to identify studies reporting preferences for LTC [25], and extracted and compiled information considered relevant to our research question (e.g., preference elicitation methods, sample, attribute/level related aspects). Second, from the obtained information we developed a questionnaire guide for semi-structured expert interviews. Twenty LTC experts were interviewed in 07–09/2014 concerning various issues regarding LTC preferences and service use, as well as LTC reform in Germany [26]. The findings were used to develop the DCE design and to provide guidance on methodological aspects. Third, information gathered in the first two steps was consolidated and discussed in an interdisciplinary team of researchers. Aiming to identify the most relevant aspects of HCBS from the perspective of LTC insurance beneficiaries and to limit the number of attributes/levels to reduce task-complexity [27], the research team reduced the initially identified seven attributes to five, with 2–4 levels each (Table 1). Fourth, understanding of the attributes and levels was tested in a small, non-random sample of potential study participants (n = 15), i.e., individuals aged ≥ 45 years from the general population in Germany. Based on participants’ comments from this qualitative pilot, attributes and levels were finalized (e.g., wording and display of information).

Experimental design

The number of attributes and their levels identified during the step-wise qualitative approach determined the total set of possible HCBS packages. To minimize respondents’ burden, a D-efficient experimental design was used to reduce the number of choices in the experiment to 16. The respective fractional factorial design was developed using the Mktex macro in SAS [28]. It incorporated data from a small, non-representative quantitative pre-test with 28 subjects aged 45–64 years, and was optimized to estimate the main effects of the attributes and their levels using a Bayesian design algorithm that integrates the D-optimality criterion over a prior distribution of likely parameter values derived from the pre-test [29].

Sample

Data for the DCE were gathered, with the assistance of a market research company (USUMA, Berlin, Germany), as part of a mixed-mode data collection effort on LTC preferences in the German general population aged ≥ 45 years between 12/2015 and 06/2016. For the total sample aged ≥ 45 years, households were randomly selected from all registered private telephone numbers (using the Guidelines for Telephone Surveys from the ADM Arbeitskreis Deutscher Markt- und Sozialforschungsinstitute e.V.). The numbers were computer-generated, allowing for ex-directory households. Repeat calls were conducted at different times on different days of the week until an answer was given; the number was dropped after the tenth attempt without an answer. At the household level, individuals were randomly selected for inclusion using the Kish-selection grid.

While individuals ≥ 65 years were invited to participate in a telephone survey [30], those aged 45–64 years were recruited for the DCE survey. Recruits were first asked to provide their mail address for the delivery of the questionnaire, but were offered to take the DCE survey online when refusing to provide a physical mail address. The total expected DCE sample equaled 5160 individuals. Thereof, 1909 individuals were recruited by phone, 1685 agreed to participate in the mail in survey, the remainder (n = 224) opted for the online survey. A total of n = 1209 of the recruited individuals successfully provided data for the DCE (response rate: 23.4%), the large majority of n = 1137 (94%) had no missing data (see, electronic supplementary material, Figure S1).

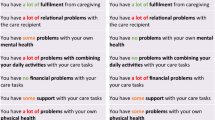

The questionnaire

The questionnaire contained: an introduction of the study purpose, instructions as to how the questionnaire is to be completed (including a separate table explaining the attributes and levels), a vignette describing an elderly person with functional limitations, the sixteen choice-sets, and twelve additional questions regarding age, gender, education, income, living situation, current LTC insurance claimant, likelihood for informal care (if care dependent), experience as informal caregiver and existence of supplemental LTC insurance. Prior to the choice exercises, participants were asked to imagine themselves in the situation illustrated in a vignette, which describes an elderly person with health problems, functional limitations, and in need of LTC (Fig. 1). The purpose of the vignette was to imply, and hold constant (between respondents) a realistic level of care needs for the hypothetical HCBS packages. This seems particularly prudent in a population where few individuals have actual care needs (3% of respondents were LTC insurance claimants) and in light of the fact that the level (and type of) care needs are a predictor for LTC preferences [25].

As pointed out above, while the main mode of data collection were mailed (self-administered) questionnaires, for individuals unwilling to provide a physical mail address, the questionnaire was made available online. Both the printed and online questionnaires were identical. To minimize position and order effects, two versions of the questionnaire, with the order of the 16 choice-sets reversed in the second version (everything else being identical), were randomly distributed among those recruited.

Ethical consideration

The study was approved by the responsible ethics committee (Ethik-Kommission der Ärztekammer Hamburg; PV4781) prior to beginning the project. Participants provided their explicit oral informed consent during the recruitment phase by agreeing to participate (providing a mail/e-mail address). Oral consent is common in survey research in Germany; the ethical guidelines of the International Code of Marketing and Social Research Practice by the International Chamber of Commerce and the European Society for Opinion and Marketing Research were followed. Recruited individuals gave implicit consent by returning the questionnaire. Personally identifying information were not collected and participant responses were anonymized prior to analysis.

Data analysis

The overall response rate for the DCE survey was 23.4%. Where valid information on the distribution of relevant characteristics was available from official statistics (micro-census) for the age group 45–64 years (i.e., age, gender, inhabitants), the distribution of these characteristics was corrected using appropriate design-weights prior to data analysis.

Of the 1209 questionnaires returned, 72 (6%) had missing data. A comparison of socio-demographic variables between respondents with complete and incomplete questionnaires did not statistically differ. Therefore, data from all 1209 respondents were included in the analysis.

Socio-demographic variables of respondents were depicted descriptively. Except for mean age and gender (% female), all remaining variables were displayed as number of cases and respective percentage shares. Equivalent income was calculated from household income as suggested by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), i.e., household income divided by the square root of the number of household members [31].

The statistical analysis is based on the random utility theory framework. The basic idea is that respondents choose the HCBS alternative that provides most utility. In random utility theory, the utility function U consists of two components: the deterministic component V that contains observable determinants, and a random component ε that represents non-observable determinants. Therefore, in the experiment the utility for respondent i of HCBS n is:

Choosing HCBS i over HCBS j in a HCBS set C for respondent n is given by:

We assumed that the error terms are independently and identically distributed with a type 1 extreme-value (Gumbel) distribution and—under this assumption—used a conditional logit model (CLM) [18, 32] to estimate the choice probabilities with:

Here γ is the scale parameter that is inversely proportional related to the standard deviation of ε. Vi is assumed to be linear in parameter:

with Xik is the kth attribute of the HCBS alternative i and βik is the regression coefficient of the kth attribute. Since the experiment included the monetary term “monthly co-payment” the marginal willingness to pay (WTP) was calculated using \( {\text{WTP}}_{\text{attribute}} \, = \,\left( {{\raise0.7ex\hbox{${\beta_{\text{attribute}} }$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\beta_{\text{attribute}} } {\beta_{\text{cost attribute}} }}}\right.\kern-0pt} \!\lower0.7ex\hbox{${\beta_{\text{cost attribute}} }$}}} \right). \)

Further information on the theoretical and econometrical underpinnings of DCE are available elsewhere [18, 20]. Akaike’s information criterium and log-likelihood was used to assess model fit. All analysis were performed using STATA version 14.

Except for time and co-payment, the remaining attribute levels are modeled as deviations from a reference level, i.e., “standard” for service level, “sufficient” for quality of care, “1–2/month” for caregivers. Equivalent income was dichotomized based on a median-split into “low” and high” income respondents. Findings are presented as preference weights (CLM coefficients) and marginal WTP for attribute levels (in comparison to the reference category). To investigate preference heterogeneity, we used a CML with interaction terms, i.e., interactions between attribute (levels) and selected personal characteristics (supplementary electronic material, Table S1).

Results

Respondent characteristics

Respondent characteristics are displayed in Table 2. Mean age was 55.7 years (standard deviation: 5.4); 51.8% were female. The sample was comparatively well-educated [33], with less than 20% of respondents indicating a low educational level. Correspondingly, mean (equivalent) income was comparatively high with €1876.

Almost one-third (31.3%) of the respondents lived in larger cities with ≥ 100.000 inhabitants. Regarding household composure, nearly half the sample (49.6%) lived in a household with two persons (including the respondent), about one-fourth (24.8%) lived by themselves, the remainder in households with ≥ 3 persons. Little less than one-fourth (23.4%) of the sample was living in East Germany (i.e., the area of the former German Democratic Republic).

With regard to personal variables pertaining to LTC, only a small share of 3% were current LTC insurance claimants, 21.4% had supplemental (private) LTC insurance, about 35% had experiences as informal caregivers. Finally, more than half of the respondents (55.5%) considered it unlikely or very unlikely to receive informal care in case of a care dependency.

Preferences for LTC (HCBS)

Table 3 presents CLM main effect coefficients and respective WTP. Findings show that all HCBS attributes were relevant to respondents, indicated by statistically significant CLM coefficients. As expected, respondents positively valued more time for care, while co-payment was valued negatively. Respondents thus preferred more time for care at lower costs. The marginal WTP for 30 min of care was €4.49, which corresponds to €8.98/h of care. Moreover, it amounts to about €270/month (30 h of care). Contrary to our expectations, respondents did not value HCBS providers with an advanced service profile (offering an extended range of services, see Table 1). In particular, respondents were willing to pay an additional €50.46 to receive care from a HCBS provider with a smaller range of services. Quality of care (QOC) had the strongest overall impact on the utility derived from HCBS, as indicated by the CLM coefficient size and respective WTP. In comparison to HCBS with “sufficient” QOC, respondents had a WTP (per month) of €130.70, €233.71 and €429.10 to receive HCBS of “satisfactory”, “high” and “very high” QOC, respectively. Finally, respondents clearly preferred regular caregivers (i.e., “1–2” different caregivers/month) over a larger number of caregivers (i.e., “3–5” and “6–8” different caregivers/month), for which they were willing to pay up to €213.86/month.

Preference heterogeneity was investigated with regard to four (dichotomized) observed variables, i.e., gender, income, informal caregiving experiences, and supplemental (private) LTC insurance. The differential impact of these variables on LTC preferences was inconsistent, except for respondents with (high) income, who had a higher WTP for HCBS in general, and higher WTP for high and very high QOC and regular caregivers in particular. Findings from the CLM with all interaction terms/effects can be found in the electronic supplementary material, Table S1.

Discussion

This study investigated preferences for (aspects of) HCBS, i.e., time for care, service level, QOC, number of caregivers, co-payment, among future LTC insurance claimants in Germany. All included attributes were statistically significant in the choice of HCBS packages, indicating their importance to respondents.

As expected, respondents valued more time for care activities and lower co-payments positively. The WTP for one extra (i.e., beyond what the German LTC insurance covers) hour of care was €8.98. Extrapolated to 1 month (30 h) this amounts to about €270. Further evidence for willingness to pay for help and care comes from a (representative) descriptive study of the adult population aged 18–79 years in Germany [34]. Respondents were asked to state their maximum WTP—beyond what is paid for by social insurance, including LTC insurance—in case they would require continuous help and care at home. Depending on household income, WTP, ranged from about €280 (income: €1000–€1499) to €1300 (income: > €5000)/month, with WTP of middle-income groups (€1000–€3000) ranging from €280 to €400, which corresponds to around €10 and €14/day, respectively.

Two studies from the Netherlands also investigated WTP per hour of care [23, 35]. A DCE eliciting preferences for (different aspects of) LTC arrangements in the Dutch general population aged 50–65 years by Nieboer et al. [23] found a lower WTP for professional care. For low-income (high-income) respondents, WTP for four extra hours of care per week was €24 (€36), which equals €6 (€9) for 1 h. WTP for informal care was elicited by van den Berg et al. [35] in two patient samples using contingent valuation [36]. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis were willing to pay €7.80/h on average, while the mean WTP was €6.72 in a sample of patients with heterogeneous indications. Differences in these WTP values may be explained, amongst others, by methodological (WTP elicitation methods) aspects and population characteristics [37].

In line with findings from a recent systematic review of studies investigating LTC preferences [25], regular caregivers in small groups were preferred to larger teams. DCE studies from the Netherlands [23] and Japan [21] also found a significant effect and positive WTP to be serviced by regular caregivers. Respondents in the current study were willing to pay up to €213.86 to receive care from regular (“1–2” different) caregivers/month. The above-mentioned study by Nieboer et al. [23] reported a WTP of €101 (€158) for regular caregivers among low-income (high-income) respondents.

QOC had the largest impact on the overall utility of HCBS packages, with step-wise increases in utility and WTP from the lowest QOC (sufficient) to higher levels of QOC. German LTC beneficiaries demand the best QOC and show a correspondingly, and in comparison to other HCBS attributes, high WTP. Interestingly, empirical evidence found that German LTC providers charging higher prices also provided higher QOC [38] and that higher QOC is associated with better quality of life in care-dependent individuals [39]. However, our operationalization of QOC in combination with peculiarities of the German LTC insurance, i.e., issues revolving around public quality reports [40], may have contributed to the finding.

In Germany, HCBS providers are audited once yearly, based on 49 individual criteria relating to different HCBS realms, i.e., basic care, medical nursing, HCBS provider organization, customer survey [40]. Evaluation results are published as public transparency reports, with overall provider quality summarized as German school grades, ranging from 1 (= very good) to 5 (= insufficient). Since most Germans are familiar with this grade system, we used it to describe the QOC attribute-levels (see, online resource 1). Transparency reports have received wide criticism, especially because of very good quality results with low dispersion (mean [median] grade of all HCBS providers in Germany in 2012 = 1.8 [1.62]; SE = 0.72) [40]. As very few HCBS providers receive grades worse than “good”, lower QOC may have been framed negatively as care deficiencies by our respondents. Such fears are not always ill-founded. A survey among 503 employees (professional caregivers) of HCBS providers in Germany found that around 21% had abused the care receiver verbally or physically at least once in the previous 12 months [41].

The results for the attribute “service level” contradicted our theoretical expectations, as well as findings from the quantitative pilot study. Surprisingly, respondents in the current study did not prefer HCBS providers offering an extended range of services (including, for instance, 24-h on-call services) over providers that offer a smaller range of services (standard). No directly comparable evidence was found, but a DCE analyzing new modes of ambulatory health care provision in the German statutory health insurance system reported a WTP of €123 for a new service consisting of individually catered personal information from patient consultants, compared to the standard information services provided by the statutory health insurance in Germany [42]. Studies analyzing preferences for different types of HCBS programs also found higher WTP for programs comprising more extensive services [20, 43], while a systematic review on preferences for consumer-directed care (CDC) models concludes that they “should offer a broad range of options that allow for personalization and greater control over services without necessarily transferring the responsibility for administrative responsibilities to services users” (p.563) [44].

We double-checked data input and variable coding of the regression model and assume that operationalizational issues may have contributed to the unexpected “service level” result. In particular, the description of the “extended” service level, may, in conjunction with the use of a vignette depicting a fragile, care-dependent, and socially isolated elderly person, which is highly dependent on the HCBS provider, have triggered fears of being totally dependent on the provider (at the providers mercy). Since utilization of the extended services has (implicit) financial implications, and in light of the fact that evidence found provider costs among the most important criteria when choosing a stationary LTC provider in Germany [45], the “extended service” level may have let respondents to imagine themselves in a situation of extreme (legal, financial and other) dependency from the HCBS provider.

Limitations

Study findings could be biased, with biases potentially stemming from different sources. Most importantly, the external validity (representativeness) of the sample may have been compromised, because of unit non-response (i.e., distribution of variables in the sample could deviate from the distribution in the population). The response rate of 23.4% is in line with other DCE in general population samples. For example, in two DCE studies on LTC conducted in the general population aged 50–65 in Japan and the Netherlands, the response rate was 15.4% [21] and 28% [23], respectively. The distribution of respondent characteristics, for which valid information in the general population aged 46–64 years in Germany was available from official statistics (i.e., age, gender, inhabitants), was corrected using appropriate design-weights prior to data analysis.

However, a comparison of educational levels (not weighted) from other studies using random samples in Germany, indicates that well-educated persons were oversampled (i.e., 14–18.2% had “high” education in previous surveys versus 41.7% in our sample), while individuals with little education were under-represented (i.e., 20.6–31.6% had “low” education versus 19.4% in our sample) [33]. Nieboer et al. [23] similarly report a markedly lower share (23.5%) of respondents with “high” education for the Netherlands, compared to our sample. While educational level was found to significantly impact (treatment) preferences in previous studies [46], possible biases stemming from the disproportionally high share of well-educated and high-income respondents [33, 47], as well as other non-response related biases are difficult to appraise without information on the extent of non-response and the characteristics of the non-responders [48].

Surveying LTC insurance beneficiaries, rather than current LTC insurance claimants (3% of the sample were LTC insurance claimants), may be seen as a limitation. However, two related DCE also surveyed future care recipients aged 45–64 years [21, 23]. The main rationale to focus on this age group was to inform future LTC system reforms. Stated preferences may not always coincide with actual service utilization in the future though [49], which may put into question the core reason to conduct stated preference studies among future service users, i.e., to increase satisfaction (and well-being) from respective care services [15]. The applicability of preference data necessarily relies on the presumption that preferences are closely linked to actual future LTC use [50]. Unfortunately, very little information available is on this topic [51, 52], especially in the realm of LTC [49].

Further limitations could be related to the conditional logit model that was used to estimate the choice probabilities. We estimated a random effect model with the constant term specified to have a random parameter and found that estimates were similar to the conditional logit model (results reported in the electronic supplementary material, Table S2). Additionally, operationalizational aspects, for instance, identification and specification of attributes and levels and the description of a care-dependent person (one vignette, no variation of care needs [23]) may imply further limitations. However, as suggested in the pertinent literature [24], we placed great emphasis on the preliminary step-wise work, including explorative literature searches, a systematic literature review [25], and expert interviews [26], amongst others.

Research and policy implications

This study was the first to analyze preferences for LTC among LTC insurance beneficiaries in Germany using a DCE. Our findings need to be verified in further preference studies [53], before firm conclusions and implications for decision-makers can be derived. As indicated above, some inconclusive findings may be explained by respondents’ individual variation to interpret some attributes of the discrete choice experiment.

Under the assumption that no biases are present, our findings have practical implications. Because of the importance of QOC to respondents, reimbursement for services by HCBS providers could be more closely linked to defined quality standards. While not easily transferable to outpatient care, recent developments in the reimbursement of inpatient services in hospitals in Germany, introduced through the Hospital Structures Act in 2015 [54], may be a starting point for quality improvement initiatives in HCBS [55, 56]. Instruments measuring the quality of care among HCBS receivers [57] and NH residents [58,59,60], may similarly constitute valuable resources. In addition to better ways to measure QOC of HCBS in Germany, presentation of public (transparency) quality reports needs to be improved as well [40].

Regarding the unexpected finding that providers offering basic HCBS were preferred over those with extended services, the vignette in combination with the description of the attribute level “Extended Service Level” may have triggered fears of high dependency from the HCBS provider. This may have resulted in low levels of perceived control over desirable outcomes, which was shown to be associated with emotional distress in elderly Germans [61]. While in principle it is possible to contract with more than one HCBS provider, almost all LTC insurance claimants in Germany receive care from a single HCBS provider. Taking this into consideration, we think that HCBS providers with a broader range of services will usually be preferred over providers with fewer services.

Evidence from the current study suggests that the stated WTP for professional HCBS (€8.98/h) is considerably below the actual hourly costs (prices) of HCBS in Germany (typically > €20/h). Moreover, WTP for HCBS is below [23] or in the same range as WTP for informal care [35]. In conjunction with the finding that informal caregivers are typically preferred over professional caregivers (when care needs are not extensive) [25], it could explain why a portion of care-dependent persons in Germany does not privately buy LTC services from HCBS providers, even though the LTC insurance covers only part of the assessed care needs [10]. While no data are available concerning how much HCBS care-dependent persons in Germany buy in addition to services provided via LTC insurance benefits, LTC experts in Germany assume that what is bought out of pocket often falls short to cover established care needs [26]. Beyond WTP being below market prices, the ability to pay for HCBS services may, in addition, be reduced among elderly (retired) LTC insurance claimants [62].

Conclusions

The current study investigated preferences for HCBS among LTC insurance beneficiaries in Germany. QOC was highly important to respondents, while providers with an extended range of services were, to our surprise, not preferred over providers with a more narrow service range. In line with previous results, small teams of regular caregivers were highly valued as well. The WTP per hour of HCBS was similar to the WTP for informal care and markedly lower than the actual costs of respective services in Germany. Our findings indicate some heterogeneity in the LTC preferences, which suggests that the utility derived from specific services differs between beneficiaries. Further studies, preferably using different types of preference elicitation techniques [53], should be conducted to investigate preferences for LTC in more detail, i.e., focusing on specific aspects of LTC.

References

United Nations Population Division: World population ageing 2013, in ST/EAS/SER.A/348. United Nations publications, New York (2013)

Rechel, B., Grundy, E., Robine, J.M., Cylus, J., Mackenbach, J.P., Knai, C., McKee, M.: Ageing in the European Union. Lancet 381(9874), 1312–1322 (2013)

Statistisches Bundesamt.: Ältere Menschen in Deutschland und der EU. (2016)

Statistisches Bundesamt.: Statistisches Jahrbuch 2016. Wiesbaden (2016)

Kluge, F.A.: The fiscal impact of population aging in Germany. Public Finance Rev. 41(1), 37–63 (2013)

Hamm, I., Seitz, H., Werding, M.: Demographic change in Germany: the economic and fiscal consequences. Springer, New York (2008)

Schulz, E., Leidl, R., Konig, H.H.: The impact of ageing on hospital care and long-term care–the example of Germany. Health Policy 67(1), 57–74 (2004)

Costa-Font, J., Wittenberg, R., Patxot, C., Comas-Herrera, A., Gori, C., di Maio, A., Pickard, L., Pozzi, A., Rothgang, H.: Projecting long-term care expenditure in four European Union member states: the influence of demographic scenarios. Soc. Indic. Res. 86(2), 303–321 (2008)

OECD: A good life in old age? Monitoring and improving quality in long-term care. OECD Health policy studies, Brussels (2013)

Rothgang, H.: Social insurance for long-term care: an evaluation of the German model. Soc. Policy Adm. 44(4), 436–460 (2010)

Campbell, J.C., Ikegami, N., Gibson, M.J.: Lessons from public long-term care insurance in Germany and Japan. Health Aff. (Millwood) 29(1), 87–95 (2010)

Statistisches Bundesamt.: Pflegestatistik 2013, Wiesbaden (2015)

Rothgang, H., Kalwitzki T., Müller R., Runte R., Unger R.: Barmer GEK Pflegereport 2015 - Schwerpunktthema: Pflegen zu Hause, Schriftenreihe zur Gesundheitsanalyse, Bd. 36. Asgard-Verlagsservice (2015)

Cvengros, J.A., Christensen, A.J., Cunningham, C., Hillis, S.L., Kaboli, P.J.: Patient preference for and reports of provider behavior: impact of symmetry on patient outcomes. Health Psychol. 28(6), 660–667 (2009)

Swift, J.K., Callahan, J.L.: The impact of client treatment preferences on outcome: a meta-analysis. J. Clin. Psychol. 65(4), 368–381 (2009)

Wiener, J.M., Anderson, W.L., Khatutsky, G.: Are consumer-directed home care beneficiaries satisfied? Evidence from Washington state. Gerontologist 47(6), 763–774 (2007)

Batavia, A.I.: Consumer direction, consumer choice, and the future of long-term care. J. Disabil. Policy Stud. 13(2), 67–74 (2002)

Ryan, M., Gerard, K., Amaya-Amaya, M.: Discrete Choice Experiments in a Nutshell. In: Ryan, M., Gerard, K., Amaya-Amaya, M. (eds.) Using discrete choice experiments to value health and health care, pp. 13–46. Springer, Netherlands (2008)

de Bekker-Grob, E.W., Ryan, M., Gerard, K.: Discrete choice experiments in health economics: a review of the literature. Health Econ. 21(2), 145–172 (2012)

Kaambwa, B., Lancsar, E., McCaffrey, N., Chen, G., Gill, L., Cameron, I.D., Crotty, M., Ratcliffe, J.: Investigating consumers’ and informal carers’ views and preferences for consumer directed care: a discrete choice experiment. Soc. Sci. Med. 140, 81–94 (2015)

Sawamura, K., Sano, H., Nakanishi, M.: Japanese public long-term care insured: preferences for future long-term care facilities, including relocation, waiting times, and individualized care. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 16(4), 350 (2015)

Brau, R., Lippi Bruni, M.: Eliciting the demand for long-term care coverage: a discrete choice modelling analysis. Health Econ. 17(3), 411–433 (2008)

Nieboer, A.P., Koolman, X., Stolk, E.A.: Preferences for long-term care services: willingness to pay estimates derived from a discrete choice experiment. Soc. Sci. Med. 70(9), 1317–1325 (2010)

Coast, J., Al-Janabi, H., Sutton, E.J., Horrocks, S.A., Vosper, A.J., Swancutt, D.R., Flynn, T.N.: Using qualitative methods for attribute development for discrete choice experiments: issues and recommendations. Health Econ. 21(6), 730–741 (2012)

Lehnert, T., Heuchert, M., Hussain K., König, H.H.: Stated preferences for long-term care: a literature review. Ageing Soc. (2018) (in press)

Heuchert, M., König, H.H., Lehnert, T.: The role of preferences in the German long-term care insurance—results from expert interviews. Gesundheitswesen 79, 1052–1057 (2016)

Petrik, O., Silva, J.D., Moura, F.: Stated preference surveys in transport demand modeling: disengagement of respondents. Transp. Lett. 8(1), 13–25 (2016)

Kuhfeld, W.: Experimental design, choice, conjoint, and graphical techniques. SAS 9.2, Toronto (2010)

Kessels, R., Jones, B., Goos, P.: Bayesian optimal designs for discrete choice experiments with partial profiles. J. Choice Model. 4(3), 52–74 (2011)

Hajek, A., Lehnert, T., Wegener, A., Riedel-Heller, S.G., Konig, H.H.: Factors associated with preferences for long-term care settings in old age: evidence from a population-based survey in Germany. BMC Health Serv. Res. 17(1), 156 (2017)

OECD: What are equivalence scales? http://www.oecd.org/els/soc/OECD-Note-EquivalenceScales.pdf (2016). Accessed 22 Dec 2016

Alberini, A., Longo, A., Veronesi, M.: Basic statistical models for stated choice methods. In: Kanninen, B.J. (ed.) Valuing Environmental amenities Using Stated Choice Methods. Springer, Berlin (2006)

Stang, A., Kluttig, A., Moebus, S., Volzke, H., Berger, K., Greiser, K.H., Stockl, D., Jockel, K.H., Meisinger, C.: Educational level, prevalence of hysterectomy, and age at amenorrhoea: a cross-sectional analysis of 9536 women from six population-based cohort studies in Germany. BMC Womens Health. 14, 10 (2014)

Müller, M.: Professionelle Pflege—Anforderungen, Inanspruchnahme und zukünftige Erwartungen, in Gesundheitsmonitor 2015. Bertelsmann Stiftung, Güterloh (2005)

van den Berg, B., Bleichrodt, H., Eeckhoudt, L.: The economic value of informal care: a study of informal caregivers’ and patients’ willingness to pay and willingness to accept for informal care. Health Econ. 14(4), 363–376 (2005)

Smith, R.D., Sach, T.H.: Contingent valuation: what needs to be done? Health Econ Policy Law 5(1), 91–111 (2010)

Bobinac, A., van Exel, J., Rutten, F.F.H., Brouwer, W.B.F.: The value of a QALY: individual willingness to pay for health gains under risk. Pharmacoeconomics 32(1), 75–86 (2014)

Geraedts, M., Harrington, C., Schumacher, D., Kraska, R.: Trade-off between quality, price, and profit orientation in Germany’s nursing homes. Ageing Int. 41(1), 89–98 (2016)

Hartgerink, J.M., Cramm, J.M., Bakker, T.J., Mackenbach, J.P., Nieboer, A.P.: The importance of older patients’ experiences with care delivery for their quality of life after hospitalization. BMC Health Serv. Res. 15(1), 311 (2015)

Sünderkamp, S., Weiß, C., Rothgang, H.: Analyse der ambulanten und stationären Pflegenoten hinsichtlich der Nützlichkeit für den Verbraucher. Pflege 27(5), 325–336 (2014)

ZQP: Gewaltprävention in der Pflege, in ZQP-Themenreport, p. 98. ZQP, Berlin (2015)

Becker, K., Zweifel, P.: Neue Formen der ambulanten Versorgung: was wollen die Versicherten? Ein discrete-choice-experiment. In: Schumpelick, V. (ed.) Medizin zwischen Humanität und Wettbewerb: Probleme, Trends und Perspektiven, pp. 313–351. Herder Freiburg, Germany (2008)

Loh, C.-P., Shapiro, A.: Willingness to pay for home- and community-based services for seniors in Florida. Home Health Care Serv. Q. 32(1), 17–34 (2013)

Ottmann, G., Allen, J., Feldman, P.: A systematic narrative review of consumer-directed care for older people: implications for model development. Health Soc. Care Community 21(6), 563–581 (2013)

Geraedts, M., Brechtel, T., Zöll, R., Hermeling, P.: Beurteilungskriterien für die Auswahl einer Pflegeeinrichtung, in Gesundheitsmonitor 2011. Bertelsmann Stiftung, Güterloh (2011)

Perez-Arce, F.: The effect of education on time preferences. Econ. Edu. Rev. 56, 52–64 (2017)

Lampert, T., Kroll, L., Muters, S., Stolzenberg, H.: Measurement of socioeconomic status in the german health interview and examination survey for adults (DEGS1). Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 56(5–6), 631–636 (2013)

Berg, N.: Non-response bias A2—Kempf–Leonard, kimberly, in encyclopedia of social measurement, pp. 865–873. Elsevier, New York (2005)

Chiu, L., Tang, K.Y., Liu, Y.H., Shyu, W.C., Chang, T.P., Chen, T.R.: Consistency between preference and use of long-term care among caregivers of stroke survivors. Public Health Nurs. 15(5), 379–386 (1998)

Unroe, K.T., Hickman, S.E., Torke, A.M., Group A.R.C.W.: Care consistency with documented care preferences: methodologic considerations for implementing the measuring what matters quality indicator. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 52(4), 453–458 (2016)

Winn, K., Ozanne, E., Sepucha, K.: Measuring patient-centered care: an updated systematic review of how studies define and report concordance between patients’ preferences and medical treatments. Patient Educ. Couns. 98(7), 811–821 (2015)

Sepucha, K., Ozanne, E.M.: How to define and measure concordance between patients’ preferences and medical treatments: a systematic review of approaches and recommendations for standardization. Patient Educ. Couns. 78(1), 12–23 (2010)

Ryan, M., Scott, D.A., Reeves, C., Bate, A., van Teijlingen, E.R., Russell, E.M., Napper, M., Robb, C.M.: Eliciting public preferences for healthcare: a systematic review of techniques. Health Technol. Assess. 5(5), 1–186 (2001)

Magunia, P., Keller, M., Rhode, A.: Auswirkungen der qualitätsorientierten Vergütung. Der Unfallchirurg. 119(5), 454–456 (2016)

Abrahamson, K., Myers, J., Arling, G., Davila, H., Mueller, C., Abery, B., Cai, Y.: Capacity and readiness for quality improvement among home and community-based service providers. Home Health Care Serv. 35, 182–196 (2016)

Kane, R.A., Cutler, L.J.: Re-imagining long-term services and supports: towards livable environments, service capacity, and enhanced community integration, choice, and quality of life for seniors. Gerontol. 55(2), 286–295 (2015)

Van Haitsma, K., Curyto, K., Spector, A., Towsley, G., Kleban, M., Carpenter, B., Ruckdeschel, K., Feldman, P.H., Koren, M.J.: The preferences for everyday living inventory: scale development and description of psychosocial preferences responses in community-dwelling elders. Gerontologist 53(4), 582–595 (2013)

Van Haitsma, K., Crespy, S., Humes, S., Elliot, A., Mihelic, A., Scott, C., Curyto, K., Spector, A., Eshraghi, K., Duntzee, C., Heid, A.R., Abbott, K.: New toolkit to measure quality of person-centered care: development and pilot evaluation with nursing home communities. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 15(9), 671–680 (2015)

Edvardsson, D., Innes, A.: Measuring person-centered care: a critical comparative review of published tools. Gerontologist 50(6), 834–846 (2010)

Degenholtz, H.B., Resnick, A.L., Bulger, N., Chia, L.: Improving quality of life in nursing homes: the structured resident interview approach. J. Ageing Res. 2014, 8 (2014)

Kunzmann, U., Little, T., Smith, J.: Perceiving ControlA double-edged sword in old age. J. Gerontol. 57(6), P484–P491 (2002)

Bakx, P., de Meijer, C., Schut, F., van Doorslaer, E.: Going formal or informal, who cares? The influence of public long-term care insurance. Health Econ. 24(6), 631–643 (2015)

Funding

This work was supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) (Grant Number: 01EH1101B).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed consent

The study was approved by the responsible ethics committee (Ethik-Kommission der Ärztekammer Hamburg; PV4781) prior to beginning the project. Participants provided their explicit oral informed consent during the recruitment phase by agreeing to participate (providing a mail/e-mail address). Oral consent is common in survey research in Germany; the ethical guidelines of the International Code of Marketing and Social Research Practice by the International Chamber of Commerce and the European Society for Opinion and Marketing Research were followed. Recruited individuals gave implicit consent by returning the questionnaire. Personally identifying information were not collected and participant responses were anonymized prior to analysis.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lehnert, T., Günther, O.H., Hajek, A. et al. Preferences for home- and community-based long-term care services in Germany: a discrete choice experiment. Eur J Health Econ 19, 1213–1223 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-018-0968-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-018-0968-0