Abstract

Contrary to traditional economic postulates, people do not only care about their absolute position but also about their relative position. However, empirical evidence on positional concerns in the context of health is scarce, despite its relevance for health care policy. This paper presents a first explorative study on positional concerns in the context of health. Using a ‘two-world' survey method, a convenience sample of 143 people chose between two options (having more in absolute terms or having more in relative terms) in several health and non-health domains. Our results for the non-health domains compare reasonably well to previous studies, with 22–47 % of respondents preferring the positional option. In the health domain, these percentages were significantly lower, indicating a stronger focus on absolute positions. The finding that positional concerns are less prominent in the health domain has important implications for health policy, for instance in balancing reduction of socio-economic inequalities and absolute health improvements.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Traditionally, economic models assume rational, self-interested decision-makers. This ‘homo economicus’ derives utility from his own endowment of goods and services, regardless of how others are endowed. Under this assumption, an income increase of €100 will always result in a utility increase, regardless of what happens to others’ incomes simultaneously (e.g. remaining stable or increasing by €200). Many have argued that this assumption regarding human behaviour is descriptively flawed. Veblen [1] already observed that individuals consume certain goods with the primary goal of displaying social status to others, that is, to emphasise their relative position. Moreover, John Stuart Mill allegedly concluded: “Men do not desire merely to be rich, but to be richer than other men”. Despite an absolute increase in his income of €100, an individual could thus perceive to be worse off when others’ incomes increase by €200. People thus care not only about what they have (in isolation)—i.e. their absolute position—but also about how their endowment compares to that of others—i.e. their relative position [2, 3].

Acknowledging the existence of these ‘positional concerns’ has important practical implications for the welfare economic evaluation of policies. Traditionally, any policy that, in absolute terms, makes some or all individuals better off without making anyone worse off, would be evaluated as a Pareto improvement. However, when positional concerns matter, this need not be the case. People may perceive an absolute, yet unequal, improvement for all, as a relative worsening of their position. This may lead them to evaluate the new situation as a loss, despite the absolute improvement.

Positional concerns are also relevant in the field of health care. For example, in the Netherlands, an initiative to treat employees on a waiting list for care with priority (in evenings and weekends) was banned, even though this would have reduced waiting times for all patients [4]. The fact that the absolute waiting time would be reduced more for some than for others, so that the relative position of non-employees worsened, was crucial in this decision. The importance of relative positions in health care policy may also be illustrated by the strong focus on reducing socio-economic inequalities in health (e.g. [5–7]), which may, although need not necessarily, be at variance with introducing health programs yielding (unequal) absolute improvements for all.

Research directly investigating positional concerns in the context of health is scarce. Two previous studies suggest that health is among the least positional domains [8, 9], but neither investigated the health domain in depth. However, there is more indirect evidence on social comparison and relative health. For example, subjective health measurements seem to be influenced by health in relevant comparison groups [10, 11]. In obesity research, evidence suggests that obesity spreads through social networks [12, 13]. Although similarity in environmental factors (food prices, number of fast food restaurants in the area, etc.) for members belonging to a social group may play a role [14], so may positional concerns. That is, body weight, dieting decisions and body weight perception are found to be influenced by relative body weight [15, 16].

This paper presents an exploratory study directly and elaborately investigating positional concerns in the context of health. It does so by repeating a well-known experiment [17] and extending it elaborately into the health domain. This offers the opportunity to compare positional concerns for health to those in other domains as well as between different aspects within the health domain. To our knowledge, this is the first study to do so in this manner.

It is important to note that this paper investigates how people value their own health in comparison to that of others, in the context of (hypothetical) trade-offs between absolute and relative positions. Our study does not investigate to what extent people care about the health of others in general (for example, as in the family effect [18, 19]).

It has been suggested that the extent of positional concerns depends on the nature of the goods in question. That is, positional concerns are thought to be more prominent when goods satisfy a need above subsistence than when they satisfy a need below this level (e.g. [20–22]). In addition, some goods may be considered basic goods, while others are labelled as luxury goods. While basic goods may satisfy needs below or above subsistence level, luxury goods always satisfy needs above subsistence level. Across domains, we may expect the extent of positional concerns to depend on the nature of goods in terms of their necessity. In the health domain, we expect to find low levels of positional concerns because in general, health care can be considered a basic good.

Methods

In order to investigate positional concerns, a questionnaire was developed to elicit preferences for absolute versus relative positions. Positional concerns were measured using the ‘two-world’ survey method introduced by Solnick and Hemenway [17]. Two hypothetical states of the world were presented, the ‘positional’ (A) and the ‘absolute’ (B). For example:

-

A.

Your current yearly income is €30,000; others earn €15,000.

-

B.

Your current yearly income is €60,000; others earn €100,000.

In the positional state A, the respondent has more of an attribute than the average other in society. In the absolute state B, the respondent had less of the attribute than the average other, but more than in the positional state. Respondents were asked which state they preferred.

The questionnaire we used for this study consisted of three parts. In part A, general demographic information was gathered. Part B was the original Solnick and Hemenway [17] questionnaire, adjusted for the Dutch context (e.g. the number of weeks of vacation were adapted), to explore positional concerns for attributes related to labour (income, education and vacation time), personal characteristics (attractiveness and intelligence) and performance at work (praise and being berated) (see “Appendix A”). Part C consisted of 14 questions on positional concerns for a variety of health- and healthcare-related attributes (see “Appendix B”). One question was disregarded here because the printed version of the questionnaire contained a mistake.

Following Solnick and Hemenway [17], the questionnaire was distributed in a ‘gain’ version, in which the positional state was presented first and the absolute second, and a ‘loss’ version in which this order was reversed. This served as a robustness check to account for the empirical findings that individuals tend to prefer the status quo [23] and value gains differently from losses [24].

Data were collected from a small convenience sample of the Dutch general public. Respondents were recruited in 2005 by one of the authors, via social networks and on the campus of the Erasmus University Rotterdam. Questionnaires were distributed on paper. A total of 143 respondents completed the questionnaire, one of whom failed to answer part C. The gain and loss versions were distributed randomly and evenly across respondents (72 for gain and 71 for loss). Females, respondents with medium or high income and respondents with a degree from higher education were over-represented; respondents in the age groups 35–44 and 55 and above were slightly under-represented (Table 1).

The average proportion of positional choices in parts B and C (the non-health and the health domain) was compared using a Wilcoxon signed rank test for comparison within subjects. This test was also used to compare the proportions of positional responses between questions within parts B and C. The responses in the gain and loss versions of the questionnaire were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test for comparison between subjects.

Results

Our results compare reasonably well to those obtained in the US by Solnick and Hemenway [17] and confirm that positional concerns are less prominent in the health domain.

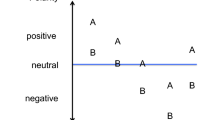

Tables 2, 3 report the percentages of respondents choosing the positional alternative in parts B and C. In general, positional concerns appear to be lower in part C. For the questions in part B, 22–47 % of the respondents chose the positional alternative; this was 11–31 % in part C. In fact, ‘age child’ (Q12) and ‘privacy’ (Q5) were the only attributes in the health domain that were more positional than the least positional attribute in part B (vacation time; Q8), as clearly shown in Fig. 1a, b. Overall, the proportion of positional choices in part C was lower than in part B (P < 0.001).

Figure 1a indicates that in the non-health domains, the attributes related to labour (income, education, and vacation time) are less positional than attributes related to personal characteristics (attractiveness and intelligence) and performance at work (praise and being berated). Pair-wise comparisons between each of the questions confirmed that the five smallest percentages (the labour-related attributes) were each significantly smaller than the five largest percentages (personal characteristics and praise from a supervisor) (all P ≤ 0.015). The observed ranking largely resembles the results of Solnick and Hemenway [17], vacation being the least positional attribute, income and education being somewhere in the middle, and intelligence, attractiveness and praise being among the most positional. With respect to the observed strength of positional concerns, some differences were found. Notably, the proportion of positional answers in our Dutch sample ranged from 22 to 47 % versus 14 to 68 % in their US sample. Also, vacation time was somewhat less positional in the US (16 % in Q3 and 14 % in Q11 on average) than in the Netherlands (22 % in Q8 and 25 % in Q3).

The results of Fig. 1b imply that in the health domain, ‘age child’ was more positional than the other attributes. Pair-wise comparisons between the positional percentages in part C confirmed this: age child (Q12) was more positional than each other attribute (all P ≤ 0.047). In the questions related to longevity (age Q8 and Q11), the attainable age in the positional state appeared to affect the degree of positional concerns. Positional concerns were more prominent when the attainable age was 80, and less when it was 70 (part C, Q11 versus Q8; P = 0.007). Such a pattern was not observed for quality of life. In both questions, 11 % of the respondents preferred the positional state (part C, Q1 versus Q6; P = 1.000).

The gain and loss versions of the questionnaire did not yield considerably different results. Although small differences in positional concerns between the versions were found, these were significant at 1 % in 2 of the 24 questions only: income (Q1 in part B; P = 0.002) and age child (Q12 in part C; P = 0.004). Significant at 10 % were intelligence child (Q10 in part B; P = 0.054) and age (Q8 in part C; P = 0.071).

Discussion

This study set out to explore the strength of positional concerns in the context of health. Our results imply that positional concerns are less prominent in the health domain than in other life domains. This confirms and expands on previous studies [8, 9].

Before addressing the implications of our findings, some limitations of our study must be noted. First, we emphasise the exploratory nature of this study. More research in the area of positional concerns in the health domain is needed to assess the robustness of our results, preferably also using different (or various) elicitation techniques such as discrete choice experiments or techniques estimating social-comparison utility functions. A natural extension of the method used here may be to disentangle status seeking motivations from egalitarian concerns, both of which have been suggested to generate positional concerns [25]. It may also be interesting to compare positional concerns in different countries, cultural groups or generations, given the existing evidence that positional concerns may be culture dependent (e.g. [9, 26]). Second, our sample was a convenience sample of limited size. Hence, it was neither entirely representative for the Dutch general public nor large enough to examine preference heterogeneity within the sample thoroughly. Young people, highly educated people and women were over-represented. To our knowledge, two studies similar to ours with respect to part B investigated the effect of personal characteristics on positional concerns [27, 28]. Neither found a significant effect of age and gender, and Grolleau et al. [27] did not find a significant effect of education level on positional concerns, except for being berated by a supervisor. Therefore, given the exploratory nature of this study, we feel this sample suffices to highlight the importance of investigating positional concerns in the health domain. Even so, caution with interpreting the results remains important. Third, many people chose the positional option in the question regarding ‘privacy’ (sharing a room with more people in the hospital). The original assumption was that more privacy (sharing a room with fewer people) would be considered better in absolute terms. However, some of the respondents indicated that they preferred sharing a room with others (i.e. they like company). Hence, these results cannot be interpreted straightforwardly in terms of the absolute–relative distinction. Fourth, respondents were asked a series of 25 similarly couched questions, which may have led to fatigue in some respondents. We thoroughly investigated this, for instance by analysing whether the number of respondents choosing ‘undecided’ or choosing the same answer as a default (positional or absolute) increased near the end of the questionnaire. The results indicate that fatigue did not noticeably influence our results. Finally, positional concerns may be operationalised as the cardinal ranking of a person compared to the average of a relevant comparison group, as was done in this paper, but could also be operationalised as the ordinal ranking in a relevant comparison group [29]. That is, health perception may be influenced by the absolute difference in health as compared to what is observed in a relevant comparison group, but also by the number of better off or worse off people in the comparison group. This is an interesting area for future research.

Notwithstanding these limitations, our results suggest that people may not care primarily about their relative position when it comes to health and healthcare. At least, in our questions they do not care enough about their relative standing to give up some of their absolute endowment. Note that the values presented do seem to matter in this context. Providing people the choice between two states of the world at higher absolute levels resulted in more positional concerns in case of longevity (Q8 and Q11 of part C). In this domain, people may thus require minimum absolute attainment levels before becoming concerned with relative positions. Our data did not support a similar reasoning for income, since both questions on income had a positional percentage of 30 %. This is in line with the results of Clark and Senik [30], and reinforces our conclusion that income preferences may be different from health preferences. Further research is needed to investigate these attainment levels and to assess the robustness of our results with respect to the exact framing and values used. In addition, an interesting extension within the health domain would be to compare positional concerns across types of care, such as medically necessary care versus “luxury care” For example, is (medically unnecessary) aesthetic plastic surgery more positional than heart transplantation?

If confirmed, our findings imply that especially absolute improvements in the health domain may contribute to welfare, even when distributed unevenly. Note that an uneven distribution may be perceived as equitable if it for instance decreases pre-existing inequalities, but as inequitable if it amplifies them. Indeed, promoting a more equitable distribution is often at variance with attaining the highest health levels in absolute terms [31]. In light of our results, policies improving the absolute health of all citizens, but for some more than for others, could still be evaluated positively by members of society, even when adding to inequalities. It should be stressed, however, that our analysis relies solely on individual preferences and does not capture broader societal concerns or equity considerations, which are clearly important in the context of health. In so far as relative positions do play a role, policy makers should be aware that overall subjective well-being can be increased only if zero-sum game outcomes are avoided [2, 3, 32]. The normative question of whether individual preferences based on social envy should be weighted in social decision making, also needs to be addressed [33].

Concluding, this study has provided a first detailed investigation of positional concerns in the context of health. More investigation in this important area is needed, and strongly encouraged, to assess the robustness of our findings.

References

Veblen, T.: The theory of the leisure class. An economic study of institutions. Viking, New York (1912). Original work published 1899

Hirsch, F.: Social limits to growth. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA (1976)

Frank, R.H.: Choosing the right pond. Human behavior and the quest for status. Oxford University Press, New York (1985)

Brouwer, W.B.F., Schut, F.T.: Priority care for employees: a blessing in disguise? Health Econ. 8(1), 65–73 (1999)

Macintyre, S.: The black report and beyond what are the issues? Soc. Sci. Med. 44(6), 723–745 (1997)

Mackenbach, J.P., Stronks, K.: A strategy for tackling health inequalities in the Netherlands. BMJl 325(7371), 1029–1032 (2002)

Mackenbach, J.P., Bakker, M.J.: Tackling socioeconomic inequalities in health: analysis of European experiences. Lancet 362(9393), 1409–1414 (2003)

Solnick, S.J., Hemenway, D.: Are positional concerns stronger in some domains than in others? Am. Econ. Rev. 95(2), 147–151 (2005)

Grolleau, G., Said, S.: Do you prefer having more or more than others? Survey evidence on positional concerns in France. J. Econ. Issues 42(4), 1145–1158 (2008)

Powdthavee, N.: Ill-health as a household norm: evidence from other people’s health problems. Soc. Sci. Med. 68(2), 251–259 (2009)

Carrieri, V.: Social comparison and subjective well-being: does the health of others matter? Bull. Econ. Res. 64(1), 31–55 (2012)

Christakis, N.A., Fowler, J.H.: The spread of obesity in a large social network over 32 years. N. Engl. J. Med. 357(4), 370–379 (2007)

Clark, A.E., Etilé, F.: Happy house: spousal weight and individual well-being. J. Health Econ. 30(5), 1124–1136 (2011)

Cohen-Cole, E., Fletcher, J.M.: Is obesity contagious? Social networks vs. environmental factors in the obesity epidemic. J. Health Econ. 27(5), 1382–1387 (2008)

Blanchflower, D.G., Oswald, A.J., Van Landeghem, B.G.: Imitative obesity and relative utility. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 7, 528–538 (2009)

Lanza, H.I., Echols, L., Graham, S.: Deviating from the norm: body mass index (BMI) differences and psychosocial adjustment among early adolescent girls. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 38(4), 376–386 (2013)

Solnick, S.J., Hemenway, D.: Is more always better?: a survey on positional concerns. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 37(3), 373–383 (1998)

Bobinac, A., van Exel, N.J.A., Rutten, F.F.H., Brouwer, W.B.F.: Caring for and caring about: disentangling the caregiver effect and the family effect. J. Health Econ. 29(4), 549–556 (2010)

Bobinac, A., van Exel, N., Job, A., Rutten, F.F., Brouwer, W.B.: Health effects in significant others separating family and care-giving effects. Med. Decis. Making 31(2), 292–298 (2011)

Veenhoven, R.: Advances in understanding happiness. Rev. Québéc. Psychol. 18(2), 29–74 (1997)

Frank, R.H.: Passions within reason: the strategic role of the emotions. Norton, New York (1988)

Thurow, L.: The zero-sum society: distribution and the possibilities for economic change. Basic Books, New York (1980)

Samuleson, W., Zeckhauser, R.: Status quo bias in decision making. J. Risk. Uncertain. 1, 7–59 (1988)

Tversky, A., Kahneman, D.: The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. Science 211(4481), 453–458 (1981)

Celse, J.: Is the positional bias an artefact? Distinguishing positional concerns from egalitarian concerns. J. Socio Econ. 41(3), 277–283 (2012)

Solnick, S.J., Hong, L., Hemenway, D.: Positional goods in the United States and China. J. Socio Econ. 36(4), 537–545 (2007)

Grolleau, G., Mzoughi, N., Saïd, S.: Do you believe that others are more positional than you? Results from an empirical survey on positional concerns in France. J. Socio Econ. 41(1), 48–54 (2012)

Hillesheim, I., Mechtel, M.: How much do others matter? Explaining positional concerns for different goods and personal characteristics. J. Econ. Psychol. 34, 61–77 (2013)

Bilancini, E., Boncinelli, L.: Ordinal vs cardinal status: two examples. Econ. Lett. 101(1), 17–19 (2008)

Clark, A.E., Senik, C.: Who compares to whom? The anatomy of income comparisons in Europe. Econ. J. 120, 573–594 (2010)

Wagstaff, A.: QALYs and the equity–efficiency trade-off. J. Health Econ. 10(1), 21–41 (1991)

Grolleau, G., Galochkin, I., Sutan, A.: Escaping the zero-sum game of positional races. Kyklos 65(4), 464–479 (2012)

Pauly, M.V.: Who was that: straw man anyway? A comment on evans and rice. J. Health Polit. Policy Law 22, 467–473 (1997)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A

In the questions below, two states of the world are presented (state A and state B). You are asked to choose in which of the two states you would prefer to live. The questions are independent from each other. In each question, please circle either A or B, or if undecided, both A and B. ‘Others’ can be interpreted as the average other person in society.

Which world would you prefer?a

1. | A | Your current yearly income is 30,000 euro, others earn 15,000 euro |

B | Your current yearly income is 60,000 euro, others earn 100,000 euro | |

2. | A | You have 12 years of education (high school), others have 8 years (elementary school) |

B | You have 16 years of education (college), others have 20 years (graduate) | |

3. | A | You have 4 weeks of vacation, others have 2 weeks |

B | You have 6 weeks of vacation, others have 10 weeks | |

4. | A | You are berated by the supervisor 4 times this year, others are berated 8 times |

B | You are berated by the supervisor twice, others are berated once | |

Assume intelligence can be described by IQ on current tests | ||

5. | A | Your IQ is 110, others average 90 |

B | Your IQ is 130, others average 150 | |

Assume physical attractiveness can be measured on a scale from 1 (lowest) to 10 (highest) | ||

6. | A | Your physical attractiveness is 6, others average 4 |

B | Your physical attractiveness is 8, others average 10 | |

7. | A | You are praised by the supervisor 2 times this year, others are not praised |

B | You are praised by the supervisor 5 times this year, others are praised 12 times | |

8. | A | You have 1 week of vacation, others have none |

B | You have 2 weeks of vacation, others have 4 weeks | |

9. | A | Your current yearly income is 20,000 euro, others earn 10,000 |

B | Your current yearly income is 40,000, others earn 80,000 | |

Assume you have a child | ||

10. | A | Your child’s IQ is 110, other people’s children average 90 |

B | Your child’s IQ is 130, other people’s children average 150 | |

11. | A | Your child’s physical attractiveness is 6, others average 4 |

B | Your child’s physical attractiveness is 8, others average 10 | |

Appendix B

The previous questions concerned different aspects of life. The next part of the questionnaire will focus on health- and healthcare-specific situations. In each question, please circle either A or B, or if undecided, both A and B. `Others’ can be interpreted as the average other person in society.

Which world would you prefer?

Assume health can be measured on a scale from 1 (lowest) to 10 (highest) | ||

1. | A | Your health is 6, others average 4 |

B | Your health is 8, others average 10 | |

Assume you need a knee-operation | ||

2. | A | Your waiting time is 6 weeks, others wait 8 weeks |

B | Your waiting time is 3 weeks, others wait 1 week | |

3. | A | Your travel time to the hospital is 30 min, others travel 60 min |

B | Your travel time to the hospital is 15 min, others travel time 5 min | |

4. | A | Your insurance-company covers 50 % of all costs of complementary care (e.g. physiotherapy), others are not covered |

B | Your insurance-company covers 75 % of all costs of complementary care (e.g. physiotherapy), others are fully covered | |

5. | A | You get a four-person room in the hospital, others get a 6-persons room |

B | You get a two-person room in the hospital, others get a private room | |

6. | A | Your health is 4, others average 2 |

B | Your health is 6, others average 8 | |

Assume you need a cataract-operation | ||

7. | A | Your waiting time is 6 weeks, others wait 8 weeks |

B | Your waiting time is 3 weeks, others wait 1 weeks | |

8. | A | You will reach 70 years of age, others average 65 |

B | You will reach 75 years of age, others average 80 | |

Assume you need an open-heart-operation | ||

9. | A | Your waiting time is 6 weeks, others wait 8 weeks |

B | Your waiting time is 3 weeks, others wait 1 week | |

10. | A | Your co-payment for consultation at the physician is 10 euro, others pay 15 euro |

B | Your co-payment for a consultation at the physician is 5 euro, others pay 2.50 euro | |

11. | A | You will reach 80 years of age, others average 75 |

B | You will reach 85 years of age, others average 90 | |

Assume you have a child | ||

12. | A | Your child will reach 80 years, others average 75 |

B | Your child will reach 85 years, others average 90 | |

13. | A | Your child’s health is 6, others average 4 |

B | Your child’s health is 8, others average 10 | |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wouters, S., van Exel, N.J.A., van de Donk, M. et al. Do people desire to be healthier than other people? A short note on positional concerns for health. Eur J Health Econ 16, 47–54 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-013-0550-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-013-0550-8