Abstract

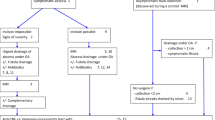

The French National Society of Coloproctology established national recommendations for the treatment of anoperineal lesions associated with Crohn’s disease. Treatment strategies for anal ulcerations and anorectal stenosis are suggested. Recommendations have been graded following international recommendations, and when absent professional agreement was established. For each situation, practical algorithms have been drawn.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Methodology

The management of anoperineal lesions (APL) in patients with Crohn’s disease (CD) is often complex and the existing recommendations date back to 2014 and do not cover all types of lesions [1]. A working group of 14 national experts in the management of APL associated with CD was formed in January 2017. Work on the development of recommendations took place between February and November 2017 and used the DELPHI methodology. For each clinical situation, the group developed a management decision algorithm based on the international recommendations, French clinical practice recommendations, available publications, and clinical/surgical experience, with graded recommendations (Table 1). The first draft was initially submitted to all group members. A summary of the corrections was made by a panel of 4 members of the group. In November 2017, all 9 decision algorithms were circulated to all members of the French National Society of Coloproctology. At the society’s national conference on November 26, 2017, the issues that were not the subject of consensus were put to the vote of the 300 delegates present. These responses were then integrated into the algorithms as “professional agreements” (PA).

Definitions

The clinical presentation is polymorphous, but differs from classical anal fissures in the pitted aspect, prominent margins and inflammatory character of the lesions; and they are sometimes associated with inflammatory markers. Their locations may be non-commissural, occasionally multiple, and readily extend above the dentate line of the lower rectum or below the anal margin or perineum. These primary lesions of Crohn’s disease can be graded according to Cardiff’s classification as U0 (no lesion), U1 (fissure or superficial ulceration) and U2 (ulcer) [2]. This grading scale established in one specialized center was based on the clinical aspect of the lesion and also on the observed evolution. U2 lesions have the poorest prognosis [2]. The cumulative probability of an AUC at 10 years after the initial diagnosis of CD is greater than 20% [3]. These lesions are an indication of disease severity and are frequently associated with ileal and especially rectal involvement [4, 5]. However, the spontaneous evolution of these lesions is poorly understood because it is rarely described in the literature.

AUCs can be painful when they are extensive or cavitating, can be complicated by anal abscesses or fistulae, and potentially lead to sphincter destruction or anal stenosis.

In France, the prevalence of CD-related anal lesions in children has been studied in a population-based cohort analysis of the EPIMAD register [8]. It included 404 children (0–17 years old) followed for more than 2 years (median follow-up 84 months). The prevalence of anal lesions was 9% at the time of diagnosis of CD and 27% at the end of the follow-up period.

Cardiff’s classification identifies three types of perianal lesions: ulceration, fistula/abscess, and stricture/stenosis, and grades them according to their severity. This is supplemented by an appendix grading the activity of the lesions and describing possible associated lesions.

Ulcerations and fissures

Evaluation

The evaluation of an anal ulceration in the context of Crohn’s disease (AUC) can be only be done by a complete proctologic examination including a systematic anuscopy and if necessary an examination under general anesthesia (GA) if an examination is impossible otherwise.

Treatment

Even for a classical anal fissure occurring in the context of Crohn’s disease, surgical treatment should be avoided, as it could fail to heal, or lead to suppuration or secondary incontinence (PA). Due to the risk of anal incontinence, it is not recommended to perform a sphincterotomy (PA).

Targeted surgeries (resection, fissurectomy, sphincterotomy) have only been reported in very limited, uncontrolled series and these procedures were performed before the era of biotherapy [9,10,11].

Before initiating medical treatment, one must first rule out abscess or associated complex fistula. If there is the slightest doubt of associated suppuration, an MRI examination with or without a clinical EUA is the strategy of choice for a thorough assessment of the AUC, particularly when there is suspicion of associated AUC.

The goal of treatment is to improve the patient’s quality of life and to avoid the occurrence of complications, such as suppuration, sphincter destruction or secondary stenosis.

There is no evidence in the literature to recommend early treatment of AUCs that are at a superficial stage and limited to Cardiff stage UI. However, depending on the overall context, treatment must be early enough to prevent the development of potentially invalidating lesions.

To date, there is no study specifically evaluating the efficacy of other biotherapies in the treatment of AUC.

A retrospective study has evaluated the efficacy of infliximab administered by perfusion at 0, 2, and 6 weeks on 27 patients with CD-related anal ulceration, with a short follow-up. At week 8, 48% and at week 24, 50% of patients had healed [12]. In a large retrospective two-center series (n = 99) with a follow-up of more than 3 years, a similar rate (42%) of healing of the AUC was observed at 12 weeks after the introduction of infliximab. In the long term (175 weeks on average), 72% (42/94) of the patients no longer presented anal ulceration, with 71% U1 classified lesions healed and 83% U2 classified lesions healed. The combination of infliximab and thiopurines was associated with better long-term healing of cavitating AUCs (p = 0.017), in contrast to more superficial anal ulcers whose evolution was not influenced by dual therapy. In 94% of patients who received maintenance treatment, induction-induced remission was maintained [13]. This potential superiority of the combination over monotherapy for CD-related anal ulcers is consistent with that observed in other severe lesions of CD such as luminal ulcerations [14] or anoperineal fistulas [15]. No data are available on the combination of infliximab and methotrexate in the treatment of AUC.

There are no studies evaluating the effectiveness of thiopurines in the healing of AUC. Only one multicenter open-label study suggested a significant reduction in the risk of occurrence of an anal lesion, including fissure and ulceration, when azathioprine was introduced immediately after the diagnosis of luminal CD, compared to secondary introduction in the event of unfavorable evolution [16].

Metronidazole treatment initiated in 53 children in the ‘Ontario cohort’ reduced complaints in 38; two-thirds of children with a fistula or abscess showed a response to the treatment; and the response was comparable in those with ulcerations [17].

In children with this indication, the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO) group recommends the use of ciprofloxacin or metronidazole antibiotics [18].

In small, open or retrospective case series, digestive diversion stoma was found to improve “refractory” Crohn’s APLs [19,20,21,22,23] as well as when taken together in a meta-analysis [24].

However, in the medium and long term, the rate of healing allowing the return of continence was low (20%), and the risk of proctectomy was high (about 40%). The presence of proctitis was an independent factor in the non-restoration of continence. These poor results do not seem to be improved by the addition of anti-TNF therapy [16, 24].

Proctectomy is indicated as a last resort for severe refractory anorectal lesions, after failure of other medical and surgical treatment. While it allows an improvement in the quality of life of patients, it is associated with a risk of about 20% of persistent perineal sinus and the frequency is increased if anoperineal suppuration is present [25] and management is challenging [19, 26].

Anal or rectal stenosis

Evaluation

The evaluation of anorectal stenosis in CD requires clinical examination, sometimes under anesthesia, endoscopic examination and MRI, to describe the stenosis itself and to identify associated anoperineal lesions whether inflammatory, infectious or dysplastic.

It is recommended to accurately describe the stenosis (its position relative to the anal margin, its length and its size), to evaluate its clinical impact by looking for dyschezia or continence disorders, or using the Perianal Disease Activity Index (PDAI) [27] and to look for other anoperineal lesions (ulceration, fistula, abscess) (Figs. 1, 2).

According to the ECCO consensus, when a radiological assessment of Crohn’s APL is required, it is recommended to perform an MRI examination (Grade B) [28] to complement the clinical examination (under general anesthesia if needed); it is also recommended to carry out an assessment of luminalCd.

Despite the lack of specific epidemiological data on the frequency of stenotic cancers, biopsies are recommended to search for dysplasia or neoplasia.

This assessment is essential because the treatment depends on the characteristics of the stenosis, the existence, or not, of associated perineal disease, and the existence of luminal involvement in CD (activity, dysplasia).

Treatment

If a stenosis is associated with fistulising perineal lesions, it is recommended to first treat the suppuration medically and/or surgically, with or without dilatation [29]. This intervention should be guided by the MRI data. In case of complex and recurrent suppuration, it may be necessary to propose a temporary derivative stoma.

Type 1 inflammatory anorectal stenosis (Cardiff classification) should be treated medically in the same way as luminal CD [2].

Cardiff type 2 stenosis [2] should be treated using a simple minimally invasive procedure [29]. The dilatation consists of increasing the diameter of the anus or rectum, by a mechanical release of the fibrosis. It should be performed in an operating room under general or locoregional anesthesia, following a thorough anorectal and perineal examination. It may be necessary to repeat the dilatation to obtain a sufficiently large passage.

The diameter must be adapted to the risk of continence disorders, signs of obstruction or occlusion and be sufficient to perform an endoscopy with biopsies at and above the stenosis.

Conclusions

Literature about treatment of anal ulceration and anorectal stenosis associated with CD is scarce. These recommendations add expert and professional agreement to available demonstrated data and, therefore, can help specialists to discuss optimal treatment for these difficult patients.

The only medical treatment of AUCs that has proven effectiveness is based on anti-TNF+/− and an immunosuppressor. Medical treatment with anti-TNF that induces remission must be continued as maintenance therapy.

In case of anal or rectal stenosis, thorough assessment is necessary, including a clinical examination, possibly under general anesthesia, MRI and endoscopy with biopsies of the stenosis and upstream, possibly following dilation due to the risk of degeneration. The first-line treatment of an inflammatory anal or rectal stenosis should be medical. The recommended first-line treatment of an isolated fibrous stenosis is dilatation of the stenosis.

Abbreviations

- AUC:

-

Anal ulceration of Crohn’s disease

- APL:

-

Ano-perineal lesion

- CD:

-

Crohn’s disease

- PA:

-

Professional agreement

- EA:

-

Expert agreement

- MRI:

-

Nuclear magnetic resonance imaging

- IS:

-

Immunosuppressant

References

Bouchard D, Abramowitz L, Bouguen G, Brochard C, Dabadie A, de Parades V, Eleuet-Kaplan M, Fathallah N, Faucheron J-L, Maggiori L, Panis Y, Pigot F, Roume P, Roumeguere P, Sénéjoux A, Siproudhis L, Staumont G, Suduca J-M, Vinson-Bonnet B, Zeitoun J-D (2017) Anoperineal lesions in Crohn’s disease: French recommendations for clinical practice. Tech Coloproctol 21:683–691

Hughes LE (1992) Clinical classification of perianal Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum 35:928–932

Schwartz DA, Loftus EV Jr, Tremaine WJ, Panaccione R, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Sandborn WJ (2002) The natural history of fistulizing Crohn’s disease in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Gastroenterology 122:875–880

Eglinton TW, Roberts R, Pearson J et al (2012) Clinical and genetic risk factors for perianal Crohn’s disease in a population-based cohort. Am J Gastroenterol 107:589–596

Siproudhis L, Mortaji A, Mary JY, Juguet F, Bretagne JF, Gosselin M (1997) Anal lesions: any significant prognosis in Crohn’s disease ? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 9:239–243

Horaist C, de Parades V, Abramowitz L et al (2017) Elaboration and validation of Crohn’s disease anoperineal lesions consensual definitions. World J Gastroenterol 23:5371–5378

Travis S, Van Assche G, Dignass A, Cabré E, Gassull MA (2010) On the second ECCO Consensus on Crohn’s disease. J Crohns Colitis 4:1–6

Vernier-Massouille G, Balde M, Salleron J, Turck D, Dupas JL, Mouterde O, Merle V, Salomez JL, Branche J, Marti R, Lerebours E, Cortot A, Gower-Rousseau C, Colombel JF (2008) Natural history of pediatric Crohn’s disease: a population-based cohort study. Gastroenterology 135:1106–1113

Fleshner PR, Schoetz DJ Jr, Roberts PL, Murray JJ, Coller JA, Veidenheimer MC (1995) Anal fissure in Crohn’s disease: a plea for aggressive management. Dis Colon Rectum 38:1137–1143

D’Ugo S, Franceschilli L, Cadeddu F, Leccesi L, Blanco Gdel V, Calabrese E, Milito G, Di Lorenzo N, Gaspari AL, Sileri P (2013) Medical and surgical treatment of haemorrhoids and anal fissure in Crohn’s disease: a critical appraisal. BMC Gastroenterol 13:11 47.

Wolkomir AF, Luchtefeld MA (1993) Surgery for symptomatic hemorrhoids and anal fissures in Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum 36:545–547

Ouraghi A, Nieuviarts S, Mougenel JL et al (2001) Infliximab therapy for Crohn’s disease anoperineal lesions. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 25:949–956

Bouguen G, Trouilloud I, Siproudhis L et al (2009) Long-term outcome of non-fistulizing (ulcers, stricture) perianal Crohn’s disease in patients treated with infliximab. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 30:749–756

Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Reinisch W et al (2010) SONIC Study Group. Infliximab, azathioprine, or combination therapy for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med 362:1383–1395

Bouguen G, Siproudhis L, Gizard E et al (2013) Long-term outcome of perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease treated with infliximab. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 11:975–81.e1-4

Cosnes J, Bourrier A, Laharie D et al (2013) Groupe d’Etude Thérapeutique des Affections Inflammatoires du Tube Digestif (GETAID). Early administration of azathioprine vs conventional management of Crohn’s Disease: a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology 145:758–765

Palder SB, Shandling B, Bilik R, Griffiths AM, Sherman P (1991) Perianal complications of pediatric Crohn’s disease. J Pediatr Surg 26:513–515

Ruemmele FM, Veres G, Kolho KL, European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation, European Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition et al (2014) Consensus guidelines of ECCO/ESPGHAN on the medical management of pediatric Crohn’s disease. J Crohns Colitis 8:1179–1207

Yamamoto T, Allan RN, Keighley MR (2000) Effect of fecal diversion alone on perianal Crohn’s disease. World J Surg 24:1258–1262

Regimbeau JM, Panis Y, Pocard M et al (2001) Long-term results of ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for colorectal Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum 44:769–778

Gu J, Valente MA, Remzi FH, Stocchi L (2015) Factors affecting the fate of faecal diversion in patients with perianal Crohn’s disease. Colorectal Dis 17:66–72

Bafford AC, Latushko A, Hansraj N, Jambaulikar G, Ghazi LJ (2017) The use of temporary fecal diversion in colonic and perianal crohn’s disease does not improve outcomes. Dig Dis Sci 62:2079–2086

Hong MK, Craig Lynch A et al (2011) Faecal diversion in the management of perianal Crohn’s disease. Colorectal Dis 13:171–176

Singh S, Ding NS, Mathis KL, Dulai PS, Farrell AM, Pemberton JH, Hart AL, Sandborn WJ, Loftus EV Jr (2015) Systematic review with meta-analysis: faecal diversion for management of perianal Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 42:783–792

Li W, Stocchi L, Elagili F, Kiran RP, Strong SA (2017) Healing of the perineal wound after proctectomy in Crohn’s disease patients: only preoperative perineal sepsis predicts poor outcome. Tech Coloproctol 21:715–720

Adam S (2000 May) Perineal wound morbidity following proctectomy for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Colorectal Dis 2(3):165–169

Irvine EJ (1995) Usual therapy improves perianal Crohn’s disease as measured by a new disease activity index. McMaster IBD Study Group. J Clin Gastroenterol 20:27–321

Panes J, Bouhnik Y, Reisnish W et al, Imaging techniques for assessment of inflammatory bowel diseases: joint ECCO and ESGAR evidence based consensus guidelines. J Crohns Colitis 7:556–585

Linares L, Moreira LF, Andrews H, Allan RN, Alexander-Williams J, Keighley MR (1988) Natural history and treatment of anorectal strictures complicating Crohn’s disease. Br J Surg 75(7):653–655

Funding

This work was supported by the French National Society of Coloproctology (SNFCP) and the Groupe d’Etudes Thérapeutique des Affections Inflammatoires du Tube Digestif (GETAID).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Bouchard D: Abbvie, Takeda (consultant and lecture fees), Pigot F : Abbvie (lecture fees), Abramowitz L : Abbvie, Takeda (research fees), Faucheron JL : AMI, Medtronic (consultant, research fees), Laharie D : Abbvie, Janssen, MSD, Takeda (board, lectures fees), Siproudhis L : Abbvie, Ferring, MSD, Takeda (teaching sessions, consultant, research fees). The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

For this type of study formal consent is not required.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bouchard, D., Brochard, C., Vinson-Bonnet, B. et al. How to manage anal ulcerations and anorectal stenosis in Crohn’s disease: algorithm-based decision making. Tech Coloproctol 23, 353–360 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-019-01971-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-019-01971-6