Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to evaluate the impact of Surgical Unit volume on the 30-day reoperation rate in patients with CRC.

Methods

Data were extracted from the regional Hospital Discharge Dataset and included patients who underwent elective resection for primary CRC in the Veneto Region (2005–2013). The primary outcome measure was any unplanned reoperation performed within 30 days from the index surgery. Independent variables were: age, gender, comorbidity, previous abdominal surgery, site and year of the resection, open/laparoscopic approach and yearly Surgical Unit volume for colorectal resections as a whole, and in detail for colonic, rectal and laparoscopic resections. Multilevel multivariate regression analysis was used to evaluate the impact of variables on the outcome measure.

Results

During the study period, 21,797 elective primary colorectal resections were performed. The 30-day reoperation rate was 5.5 % and was not associated with Surgical Unit volume. In multivariate multilevel analysis, a statistically significant association was found between 30-day reoperation rate and rectal resection volume (intermediate-volume group OR 0.75; 95 % CI 0.56–0.99) and laparoscopic approach (high-volume group OR 0.69; 95 % CI 0.51–0.96).

Conclusions

While Surgical Unit volume is not a predictor of 30-day reoperation after CRC resection, it is associated with an early return to the operating room for patients operated on for rectal cancer or with a laparoscopic approach. These findings suggest that quality improvement programmes or centralization of surgery may only be required for subgroups of CRC patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common cancers worldwide. It is associated with a low rate of post-operative mortality, but with a high rate of post-operative morbidity for rectal cancer surgery and for surgery performed in an emergency setting.

The outcomes of CRC vary widely, depending on both the patients and tumour characteristics, as well as the quality of treatments administered. There is therefore a growing interest in indicators that are able to measure the quality of treatment and factors that can affect such indicators.

The choice of the surgical quality performance indicators varies depending on how frequently is the outcome observed and how the quality indicator impacts the outcome and the ease and reliability in measurement of the indicator [1]. Some quality indicator measures rely on the long-term outcomes, while others rely on short-term outcomes. Furthermore, they can be independent or evaluated within a composite outcome [2, 3].

Among several short-term surgical quality performance indicators for CRC, the rate of reoperation within 30 days from the index surgery has been proposed as a reliable indicator, and is retrievable from large administrative population-based databases [4–7]. It may be influenced by many variables, including surgeon and institution volume and specialization [8], laparoscopic or open approach [9] and the specific site of the primary tumour [8, 10]. An improved understanding of the relationship between such variables and the rate of reoperation may be relevant in comparing performance between providers and consequently in making decisions at the clinical, managerial and political levels as well as planning programmes to improve CRC surgery.

The principal aim of this study was therefore to evaluate the relationship between the rate of surgical reoperations within 30 days from the index surgery and the Surgical Unit volume for elective primary CRC in a population-based setting. A secondary endpoint was to explore the impact of the volume on the reoperation rate, with specific attention to subgroups of subjects such as rectal cancer patients and patients operated on laparoscopically.

Patients and methods

Data source

The Veneto Region is a North-East Italian region with 5 million inhabitants. Health service is provided by regional administration and includes Surgical Units, all of which are able to perform any CRC surgical procedure. Only 3.2 % of residents are operated on outside of the region. Moreover, in the last decade, the regional population aged from 50 to 69 years was increasingly screened for CRC reaching a maximum level of 81.4 % [11].

The regional Hospital Discharge Dataset was the primary information source. The form, compiled at discharge, reports patient demographics, the date of the admission and discharge, the codes of the primary and secondary diagnoses, the dates and the codes of up to six procedures performed (both codes being reported according to International Classification of Diseases 9th Revision Clinical Modification 2007, ICD-9-CM), the American Anaesthesiologist Association (ASA) score and whether the surgical procedure was performed in an emergent or elective setting. At the time of the admission, the functional Barthel index [12] is recorded.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

This study included all resident patients in the Veneto Region, aged 18 + years, with a diagnosis of colon (ICD9-CM 153.x, 230.3) and rectal cancer (ICD9-CM 154.x, 230.4) who underwent primary elective surgery from 1 January 2005 to 31 December 2013. The following ICD9-CM procedures were included: 45.7x, 45.8, 48.35, 48.49, 48.5, 48.6x, 4594, 4595.

Patients excluded were those who underwent a surgical procedure for CRC from 2000 to 2004 and those who underwent surgery in an emergency setting or outside the Veneto Region. Cases who underwent surgery in Surgical Units performing only a single procedure in a given year were excluded.

Outcome measure

The 30-day reoperation was defined as any unplanned post-operative procedure including a return in the operating room or an imaging-guided intervention within 30 days following the index surgery. These were identified by analysing codes from the ICD9-CM Classification of Surgical Operations and Procedures version 4 (OPCS-4) [13] (see “Appendix” section). Interventions performed during the same day of the index surgery were excluded except when the reoperation was performed because of abdominal haemorrhage (ICD9-CM 39.98) or when it was specifically indicated that it was a relaparotomy (ICD9-CM 54.12);

Reoperations were first classified according to the procedure performed:

-

1.

Stoma formation and stoma complication.

-

2.

Colorectal resection.

-

3.

Procedures on small bowel or upper gastrointestinal tract.

-

4.

Procedure for surgical injuries of liver, spleen and urinary tract.

-

5.

Control of haemorrhage, drainage of abscess, division of early adhesions, open or laparoscopic control of intra-abdominal site.

-

6.

Complications of abdominal wound.

-

7.

Other perineal and transrectal procedures.

Then, they were grouped as follows:

-

a.

Any reoperation (1–7 of the previous classification)

-

b.

Abdominal reoperation (1–5 of the previous classification)

-

c.

Reoperation involving the gastrointestinal tract or the stoma (both formation and complication) (1–3 of the previous classification)

Patients with more than one type of reoperation were counted in each reoperation group.

The primary outcome measure was any post-operative procedural intervention performed within 30 days after the colorectal resection (index operation). The secondary outcome was reoperation involving the gastrointestinal tract or the stoma.

Independent variables

For each patient, the following independent variables were recorded: age, gender, non-CRC hospitalizations in the year before the index surgery, ASA score, Barthel index, admission for abdominal surgery during the 3 years prior to index surgery, site of the colorectal resection, laparoscopy or open approach, procedure performed before or after the implementation of the regional screening programme for CRC, year of the index operation, and number of cases operated on in each surgical department.

Age was subdivided into five classes: 18–49, 50–59, 60–69, 79–79 and 80+. The number of hospital admissions due to non-CRC disease during the year before the index surgery was taken as a rough measure of comorbidity. The Barthel index, which is a functional score of the activity of daily living [12] varying between 0 (death) and 100 (complete independence), was subdivided into two categories: 0–50 and 51–100 with a higher score indicating higher functional status. Colorectal resections were classified according to the anatomical part of the large bowel resected: right colon (from the caecum to the splenic flexure), left colon (from the descending colon to the recto-sigmoid junction), rectum and other (tumour requiring a total colectomy or proctocolectomy or an unspecified segmental resection). The year of the procedure was subdivided by year classes: 2005–2007, 2008–2009, 2010–2011 and 2012–2013.

As reported by Burns et al. [5], the yearly base caseload of each Surgical Unit was calculated for each year. Then colorectal resections as a whole and in detail colonic, rectal and laparoscopic resection caseloads were divided into tertiles to define high, intermediate and low volumes. In this way, each Surgical Unit was allowed to be assigned to different tertiles in different years.

Statistical analysis

The study design was an observational, retrospective, population-based study. Demographic, clinical and surgical risk factors for reoperation were tested using univariate and multivariate logistic regression. To take into account the hierarchical structure of the data, a multilevel multivariate logistical regression was implemented as well (first level: patient, second level: Surgical Unit), thus considering the autocorrelation among outcomes of patients treated in the same Surgical Unit.

Results

Relationship between patients/procedures and hospital volume

During the study period, a total of 21,797 elective colorectal resections for primary colorectal cancer were performed. The characteristics of patients and the surgical procedures, and their relationship with overall surgical volume of colorectal resections are summarized in Table 1.

Patients older than 70 years were more likely to undergo surgery in the intermediate-/low-volume groups compared with the high-volume group (P = 0.001). Looking at the patient’s comorbidity and functional status, there was an inverse association between hospital volume and comorbid conditions and functional status [number of hospital admissions during the prior year (P < 0.001), ASA score (P < 0.001) and Barthel index (P < 0.001)]. Additionally, a higher rate of patients in the low-volume group (7.5 %) had undergone previous abdominal operation than those in the intermediate-/high-volume group (6.5 % each) (P = 0.033). According to the anatomical site of resection, the distribution of colorectal resection between volume groups was significantly different (P < 0.001); rectal resection was more often performed in the intermediate-volume units (38.9 %) than in the high-volume (37.8 %) or in the low-volume groups (37.1 %).

Overall, a gradual decrease in colorectal resections was found after 2007, and the reduction in colorectal resections was more evident in the high-volume group compared to the intermediate-/low-volume group.

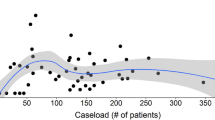

The laparoscopic approach was used in 35.7 % of cases. It was used more often in the intermediate than in low- or high-volume units (P < 0.001), and it gradually increased over time, from 27.6 % in 2005 to the 46.5 % in 2013 (Fig. 1).

Reoperations

The distribution of reoperations and the relationship between the type of reoperation and the Surgical Unit volume are summarized in Table 2. The reoperation percentage in the entire study group was 5.47 %. In these patients, a total of 1666 surgical procedures were performed, as some patients underwent more than one reoperation. While the overall and abdominal reoperation rates were not found to be significantly different when comparing the three Surgical Unit volume groups, a statistically significant difference was found in the group containing reoperations related to the stoma creation or complication, colorectal resection and small bowel or upper gastrointestinal tract procedures. The rate of reoperation in this subgroup was 3.79, 3.11 and 2.97 % (P = 0.01) in the low-, intermediate- and high-volume groups, respectively.

Risk factors for reoperation

In this analysis, ASA score and Barthel index were not included due to a high rate of missing data. The impact of variables on all reoperations is summarized in Table 3.

In the multivariate multilevel analysis, the risk of reoperation was found to be reduced in female gender (OR 0.64, CI 0.56–0.73). There was a decreased risk of reoperation in patients aged 60–69. Admission during the year prior to surgery or abdominal operation in the 3 years before the index surgery conferred a higher risk of reoperation. The laparoscopic approach was also a risk factor for reoperation (OR 1.16, CI 1.01–1.33). Comparing with low Surgical Unit volume group, reoperation risk was reduced both in the intermediate- and in the high-volume groups; these results do not reach statistical significance.

Subgroup analysis

In the multivariate logistic analysis, an inverse correlation was found between risk of reoperation and Surgical Unit volume (Table 4). However, in multilevel logistic analysis, the statistical significance was reached only for any reoperation in patients who underwent rectal resection (intermediate-volume group OR 0.75, CI 0.56–0.99) and in patients who underwent a laparoscopic approach (high-volume group OR 0.69, CI 0.51–0.96). When the outcome measure was narrowed to reoperation involving GI tract or stoma, a statistically significant association between volume and outcome was found only for patients who underwent a laparoscopic approach (high-volume group OR 0.66, CI 0.44–0.99).

Discussion

Quality performance indicators are increasing required because they may help improve quality of surgery and consequently oncological and patient-reported outcomes. Furthermore, with respect to CRC surgery, centralization of specific surgical procedures has been associated with improved outcome [14].

In this study, we evaluated whether Surgical Unit volume had an impact on the 30-day reoperation rate for elective CRC resection. This evaluation was performed in the entire study group and in subgroups of patients, specifically those who underwent colon resections, rectal resections and laparoscopic procedures. Among 21,979 patients fulfilling the entry criteria of the study, the rate reoperation was 5.5 %. While a pattern towards an association between the Surgical Unit volume and reoperation was found for CRC resections as a whole, statistical significance in favour of intermediate- and/or high-volume groups was reached only for rectal and laparoscopic resections.

In comparing our findings with similar studies in this field, certain characteristics of the study population as well as of the statistical analyses performed should be considered. In the Veneto Region, during 2013, the number of Surgical Units was quite high (more than one for every 100,000 habitants), and all of them were able to perform any CRC procedure. In addition, since 2002, a large number of 50- to 69-year-old residents have participated in a regional CRC screening programme. This situation likely explains the reduced number of patients who underwent a CRC resection after 2007 [15].

Our reoperation rate is comparable with the 5.9 % reported in the UK [5] and with the 5.8 % reported in the USA [6]. As in other studies [6], female gender was associated with a lower reoperation risk. In contrast, comorbidity and previous abdominal interventions were associated with a higher risk, while ageing was not, perhaps reflecting a careful patient selection by surgeons in taking older patients back to the operating room after primary surgery [5, 8].

Our findings are also in agreement with others [5] who found that surgery for rectal cancer is a significant risk factor for reoperation, as it is for other short-term outcome such as anastomotic leak rate [8, 16–19]. Moreover, our study brings some evidence that an association exists between Surgical Unit volume and reoperation in elective CRC resections, especially for rectal resection. Worse results were observed in Surgical Units performing no more than one rectal resection per month (Table 4). This is not surprising because rectal cancer is treated with different approaches than colon cancer, requires a multidisciplinary team and is technically demanding.

Most studies focus on the individual surgeon rather than on the hospital volume and have shown a reduction in risk of anastomotic leak [8, 17] or overall tendency for reduction in reoperation [5] when a CRC resection is performed by a high-volume surgeon. After adjustment for surgeon volume, the effect of hospital volume is generally less evident; however, an association between hospital volume and anastomotic leak after rectal resection has been described [8, 17, 20, 21].

Laparoscopic CRC resection rate increased over time as shown in Fig. 1, and during 2013, the ratio between laparoscopic and open procedures was approaching the 1:1. These figures are comparable to other recent series from the UK (47.4 %) [22] and the USA (41.0 %) [23]. In our study, the laparoscopic approach was associated with a detectable increase in reoperation rate (Table 3); learning curve in laparoscopic colorectal surgery at the individual and at the Surgical Unit level could be helpful in interpreting these data. The potential role for laparoscopic approach as a specific risk factor has been already described in many observational studies [5, 7, 24–26]. However, in a systematic Cochrane review comparing the laparoscopic with the open approach, significantly better short-term outcomes were reported in favour of the laparoscopic approach [27]. A plausible explanation of this discrepancy is that the surgeons involved in the clinical trials perform more laparoscopic procedures, while population-based studies include surgeons with less experience and worse equipment. Comparable results have been reported in recently published studies from the UK [9] and USA [28].

This study contains the expected limitations for studies based upon a Hospital Discharge Database. The most common are possible discrepancy between hospital discharge data and surgical charts, and a poor description of important factors affecting the outcomes, such as the stage of the disease and the detailed description of comorbid conditions and complications; for example, a high tumour stage may well be a reason to be operated in a higher-volume unit and is also an well-known risk factor for surgical complications. A further limitation is found the current ICD-9 CM 2007 Italian Handbook, which poorly describes conversion from laparoscopic to open surgery, allowing only an intention-to-treat analysis. Moreover, unlike others European countries, validation studies comparing hospital discharge data and clinical record have not yet been performed in Italy [29–31], nor does discharge record permit identification of the surgeon who performed each operation. [8, 10, 16–19].

The current study was focused on a single short-outcome measure, the 30-day reoperation rate, whereas other outcomes have been proposed [32, 33]. We used the 30-day post-operative reoperation rate because this outcome is retrievable from large administrative databases, is clinically relevant, and is associated with a higher risk of post-operative mortality and prolonged hospital stay [6, 34]. Post-operative mortality as a single measure of short-term outcome has been criticized because of a lack of sensitivity due to the low rate of post-operative mortality in CRC surgery [1] and because it is influenced not only by the surgery per se, but also by patient-related factors such as age and comorbidities and by surgical decision-making [28, 35]. The use of composite outcomes has also been suggested [2, 3, 33, 36] and may be an appealing method for measuring surgical quality performance.

To our knowledge, this is the first Italian study of 30-day reoperation rate following CRC resection implemented through a large Hospital Discharge Dataset.

In conclusion, our findings do not support the point of view of those who suggest indiscriminate centralization of all surgical procedures for CRC.

However, reoperation rate after rectal cancer surgery and laparoscopic resection show a clear association with Surgical Unit volume, suggesting that action is indicated in these subgroups of CRC patients. Quality of surgery can be improved through a range of interventions: supervision, teaching, accreditation or centralization [37–39].

References

Birkmeyer JD, Dimick JB, Birkmeyer N (2004) Measuring the quality of surgical care: structure, process, or outcomes? J Am Coll Surg 198:626–632

Almoudaris AM, Burns EM, Bottle A et al (2013) Single measures of performance do not reflect overall institutional quality in colorectal cancer surgery. Gut 62:423–429

Surgical Care and Outcomes Assessment Program (SCOAP) (2012) Adoption of laparoscopy for elective colorectal resection: a report from the Surgical Care and Outcomes Assessment Program. J Am Coll Surg 214:909–918

NHS Scotland—Scottish Cancer Taskforce. Colorectal cancer clinical quality performance indicators. Final Publication v2.0. November 2013. http://healthcareimprovementscotland.org/his/idoc.ashx?docid=0213323f-caae-4e15-ace7-f1f252c1e17f&version=-1. Accessed on 31 Mar 2015

Burns EM, Bottle A, Almoudaris AM et al (2013) Hierarchical multilevel analysis of increased caseload volume and postoperative outcome after elective colorectal surgery. Br J Surg 100:1531–1538

Morris AM, Baldwin L-M, Matthews B et al (2007) Reoperation as a quality indicator in colorectal surgery: a population-based analysis. Ann Surg 245:73–79

Krarup PM, Jorgensen LN, Andreasen AH, Harling H, Danish Colorectal Cancer Group (2012) A nationwide study on anastomotic leakage after colonic cancer surgery. Colorectal Dis 14:661–667

Archampong D, Borowski D, Wille-Jørgensen P, Iversen LH (2012) Workload and surgeon’s specialty for outcome after colorectal cancer surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3:CD005391

Burns EM, Mamidanna R, Currie A et al (2014) The role of caseload in determining outcome following laparoscopic colorectal cancer resection: an observational study. Surg Endosc 28:134–142

Schrag D, Panageas KS, Riedel E et al (2002) Hospital and surgeon procedure volume as predictors of outcome following rectal cancer resection. Ann Surg 236:583–592

Zorzi M, Fedato C, Cogo C et al (2015) I programmi di screening oncologici del Veneto. Rapporto 2012–2013. https://www.registrotumoriveneto.it/screening/presentazione.php

Mahoney FI, Barthel DW (1965) Functional Evaluation: the Barthel Index. Md State Med J 14:61–65

Burns EM, Bottle A, Aylin P, Darzi A, Nicholls RJ, Faiz O (2011) Variation in reoperation after colorectal surgery in England as an indicator of surgical performance: retrospective analysis of Hospital Episode Statistics. BMJ 343:d4836

Wibe A, Eriksen MT, Syse A, Tretli S, Myrvold HE, Søreide O (2005) Norwegian Rectal Cancer Group. Effect of hospital caseload on long-term outcome after standardization of rectal cancer surgery at a national level. Br J Surg 92:217–224

Zorzi M, Fedeli U, Schievano E et al (2014) Impact on colorectal cancer mortality of screening programmes based on the faecal immunochemical test. Gut 64:784–790

Borowski DW, Kelly SB, Bradburn DM et al (2007) Impact of surgeon volume and specialization on short-term outcomes in colorectal cancer surgery. Br J Surg 94:880–889

Borowski DW, Bradburn DM, Mills SJ, Northern Region Colorectal Cancer Audit Group (NORCCAG) et al (2010) Volume-outcome analysis of colorectal cancer-related outcomes. Br J Surg 97:1416–1430

Marusch F, Koch A, Schmidt U, Pross M, Gastinger I, Lippert H (2001) Hospital caseload and the results achieved inpatients with rectal cancer. Br J Surg 88:1397–1402

Marusch F, Koch A, Schmidt U et al (2001) Effect of caseload on the short-term outcome of colon surgery: results of a multicenter study. Int J Colorectal Dis 16:362–369

Harling H, Bülow S, Møller LN, Jørgensen T, Danish Colorectal Cancer Group (2005) Hospital volume and outcome of rectal cancer surgery in Denmark 1994–1999. Colorectal Dis 7:90–95

Kressner M, Bohe M, Cedermark B et al (2009) The impact of hospital volume on surgical outcome in patients with rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 52:1542–1549

Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland, Clinical Effectiveness Unit at The Royal College of Surgeons of England, The Health and Social Care Information Centre. National Bowel Cancer Audit Report 2014. http://www.hqip.org.uk/assets/NCAPOP-Library/NCAPOP-2014-15/nati-clin-audi-supp-prog-bowe-canc-2014-rep1.pdf. Accessed 02/04/2015

Moghadamyeghaneh Z, Masoomi H, Mills SD et al (2014) Outcomes of conversion of laparoscopic colorectal surgery to open surgery. JSLS 18 pii:e2014.00230

Delaney CP, Chang E, Senagore AJ, Broder M (2008) Clinical outcomes and resource utilization associated with laparoscopic and open colectomy using a large national database. Ann Surg 247:819–824

Faiz O, Warusavitarne J, Bottle A, Tekkis PP, Darzi AW, Kennedy RH (2009) Laparoscopically assisted vs. open elective colonic and rectal resection: a comparison of outcomes in English National Health Service Trusts between 1996 and 2006. Dis Colon Rectum 52:1695–1704

Bilimoria KY, Bentrem DJ, Merkow RP et al (2008) Laparoscopic-assisted vs. open colectomy for cancer: comparison of short-term outcomes from 121 hospitals. J Gastrointest Surg 12:2001–2009

Schwenk W, Haase O, Neudecker J, Müller JM (2005) Short term benefits for laparoscopic colorectal resection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 20:CD003145

Damle RN, Macomber CW, Flahive JM et al (2014) Surgeon volume and elective resection for colon cancer: an analysis of outcomes and use of laparoscopy. J Am Coll Surg 218:1223–1230

Aylin P, Bottle A, Elliott P, Jarman B (2007) Surgical mortality: hospital episode statistics v central cardiac audit database. BMJ 335:839

Garout M, Tilney HS, Tekkis PP, Aylin P (2008) Comparison of administrative data with the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland (ACPGBI) colorectal cancer database. Int J Colorectal Dis 23:155–163

Burns EM, Rigby E, Mamidanna R et al (2012) Systematic review of discharge coding accuracy. J Public Health (Oxf) 34:138–148

Almoudaris AM, Burns EM, Mamidanna R et al (2011) Value of failure to rescue as a marker of the standard of care following reoperation for complications after colorectal resection. Br J Surg 98:1775–1783

Merkow RP, Hall BL, Cohen ME et al (2013) Validity and feasibility of the American College of Surgeons colectomy composite outcome quality measure. Ann Surg 257:483–489

Mamidanna R, Burns EM, Bottle A et al (2012) Reduced risk of medical morbidity and mortality in patients selected for laparoscopic colorectal resection in England: a population-based study. Arch Surg 147:219–227

Mamidanna R, Eid-Arimoku L, Almoudaris AM et al (2012) Poor 1-year survival in elderly patients undergoing nonelective colorectal resection. Dis Colon Rectum 55:788–796

Nachiappan S, Burns EM, Faiz O (2013) Validity and Feasibility of the American College of Surgeons Colectomy composite outcome quality measure. Ann Surg 261:e158

Renzulli P, Laffer UT (2005) Learning curve: the surgeon as a prognostic factor in colorectal cancer surgery. Recent Results Cancer Res 165:86–104

Ghaferi AA, Birkmeyer JD, Dimick JB (2009) Variation in hospital mortality associated with inpatient surgery. N Eng J Med 361:1368–1375

Howell AM, Panesar SS, Burns EM, Donaldson LJ, Darzi A (2014) Reducing the burden of surgical harm: a systematic review of the interventions used to reduce adverse events in surgery. Ann Surg 259:630–641

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by a grant from the AIRC Foundation and in part by a grant from Italian Ministry of Health (RF-2011-02349645). The article was reviewed and edited for English language usage by American Journal Experts.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Informed consent was not required for this type of study.

Appendix

Appendix

See Table 5.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pucciarelli, S., Chiappetta, A., Giacomazzo, G. et al. Surgical Unit volume and 30-day reoperation rate following primary resection for colorectal cancer in the Veneto Region (Italy). Tech Coloproctol 20, 31–40 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-015-1388-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-015-1388-0