Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the outcomes of non-metastatic colon cancer patients in relation to the socioeconomic status (SES) at diagnosis based on the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) census tract level-SES database.

Methods

SEER SES census tract level database represents a specially designed database to integrate different aspects of SES among cancer patients. It reports a composite SES index for each patient. Patients were then stratified into three SES groups. Patients with a non-metastatic colon cancer diagnosis, diagnosed (2004–2015), and who were included in this specialized database were included in the current study. Multivariate Cox regression analysis was used to assess the impact of SES index on colon cancer-specific survival.

Results

A total of 80,121 patients with non-metastatic colon cancer were included in the current study. Comparing patients in the lower SES group with patients in the higher SES group, patients with lower SES were more likely to have a younger age at presentation (P < 0.001), black race (P < 0.001) and more advanced stage at presentation (P < 0.001). The impact of the SES on colon cancer-specific survival was evaluated through multivariate Cox regression analysis adjusted for age, sex, race, stage, and colon cancer side. Lower SES was associated with worse colon cancer-specific survival (hazard ratio for group 1 versus group 3: 1.257; 1.190–1.328; P < 0.001). Interaction testing between race (black race versus white race) and SES was non-significant (P = 0.932).

Conclusions

Lower SES is associated with worse colon cancer-specific survival among non-metastatic colon cancer patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Socioeconomic status (SES) is an umbrella term that encompasses a host of aspects including educational status, income, house value as well as employment status [1, 2]. Each of these factors has been shown to have a tremendous impact on the health status of individuals [3].

Interaction of these factors with cancer outcomes (including colon cancer outcomes) has been evaluated in numerous studies [4, 5]. However, the lack of a standardized tool to qualify and quantify SES has been a weakness of many of these studies. Moreover, some of these studies relate to patients treated with outdated suboptimal treatments (by current standards).

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database has long been the benchmark of population-based cancer registries. However, SES data within the SEER database were reported in a non-standardized way and each dimension of SES was reported separately (i.e. income, educational level, etc.). To overcome this limitation, a specialized SEER database integrating all relevant SES dimensions in a single index measure was produced. Moreover, this database is based on census-level data (compared to previous studies which were based on county-level data). This database should provide an enormous opportunity to clarify the impact of SES on colon cancer outcomes.

Establishing the role of SES in determining the outcomes of colon cancer is of paramount significance for practicing clinicians as well as for healthcare policymakers and it should help us better plan our healthcare system in a way that serves cancer patients.

Objective

To study the outcomes of non-metastatic colon cancer in relationship to SES based on the census-tract level SEER SES database.

Methods

About the census tract-level SEER SES database

The specialized SEER SES database was specifically designed to address the need to have a better in-depth assessment of the relationship between SES and cancer outcomes. To standardize the reporting of this database, the composite SES score (which was developed by Yost et al. and Yu et al.) was considered as the reference measure [6, 7]. Seven parameters are included in the formation of this score which represent different dimensions of SES. These include unemployment percent, working-class percent, percent below 150% of the poverty line, and education index (as proposed by Liu et al. [8]). They also include median house value and median household income. Data linkage procedures and details of geographic definitions within the context of this database were provided elsewhere [9]. This index is finally summarized as three SES tertiles (groups), where group 1 has the lowest index and group 3 has the highest index.

Selection criteria of patients in the current study

The following selection criteria were utilized to select patients for inclusion into the current study: (1) Colon adenocarcinoma diagnosis; (2) Stages I, II, III (according to American Joint Committee on Cancer 7th staging system); (3) Complete information about SES group at the time of diagnosis; (4) Diagnosis year between 2004–2015; (5) Upfront treatment with an oncologic surgical resection (including resection of the primary and regional lymph node dissection). Cases with rectal primary or non-adenocarcinoma histology were not considered for inclusion in the current study.

Data collection

The following data were obtained from the records of each included patient (if available): age at diagnosis, sex, race, SES index group, stage, side, and treatments (including surgery, chemotherapy or radiation therapy). The primary endpoint of the current study is colon cancer-specific survival (defined as the time from colon cancer diagnosis till death from colon cancer). The definition of right- versus left-sided colon cancer was based on the definition used in CALGB/SWOG 80405 trial [10]. SEER database reports chemotherapy as yes versus No/unknown; it did not separate No from Unknown groups.

Statistical analyses

Differences in clinicopathological and treatment characteristics according to the SES group were initially evaluated according to Chi-squared testing. To provide further insight into the factors affecting colon cancer-specific survival, multivariate Cox regression analysis was then used. It included the following factors: age at diagnosis, sex, Dukes’ stage, race, SES group, and colon cancer side. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy dose/schedule details were not available in the current dataset; thus, they were not included in the multivariate model.

Additional multivariate analyses were then performed to evaluate the impact of SES on colon cancer survival in clinically defined subcategories of patients (according to race, sex, side or Dukes’ stage). SPSS (version 20; IBM, NY) was utilized in performing all the above statistical analyses.

Results

Patients’ characteristics

A total of 80,121 patients with non-metastatic colon cancer were included in the current study. At the time of diagnosis, 24,368 patients were in SES group 1, 27,838 patients were in SES group 2, and 27,915 patients were in SES group 3. Comparing patients in the lower SES group with patients in the higher SES groups, patients with lower SES were more likely to have a younger age at presentation (P < 0.001), black race (P < 0.001) and more advanced Dukes’ stage at presentation (P < 0.001). They were less likely to receive radiotherapy (P < 0.001). There were, however, no difference between the three groups with regard to patients’ sex (P = 0.508) or the use of chemotherapy (P = 0.084) (Table 1). All patients included in the current analysis underwent oncologic surgery to the primary tumor and regional lymph nodes. Mean follow-up duration for each of three SES groups was as follows: group 1:27.70, SD: 20.68; group 2:28.84, SD: 28.80; group 3 29.67, SD: 20.84.

Impact of SES on colon cancer-specific survival in the overall cohort

The impact of SES on colon cancer-specific survival was evaluated through multivariate Cox regression analysis. Lower SES was associated with worse colon cancer-specific survival (hazard ratio for group 1 versus group 3: 1.257; 1.190–1.328; P < 0.001) (Table 2). Interaction testing between the race (black race versus white race) and SES was non-significant (P = 0.932).

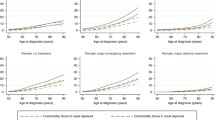

Impact of SES index on colon cancer-specific survival in specific subgroups (according to colon cancer side and stage, and according to patients’ sex and race)

Table 3 detailed the impact of SES index on colon cancer-specific survival according to the side (right versus left). This was done through multivariate Cox regression modeling for each of the two sides adjusted for age at diagnosis, sex, race, and stage. Lower SES predicts poorer colon cancer-specific survival among patients having disease on either side of the colon (P < 0.001 for group 1 versus group 3 among both sides).

Likewise, the impact of SES on colon cancer-specific survival according to the stage (Dukes’ stage A vs. B vs. C) was assessed (Table 4). This was assessed through multivariate Cox regression model adjusted for age at diagnosis, sex, race, and side. Lower SES predicts poorer colon cancer-specific survival regardless of disease stage (P < 0.001 for group 1 versus group 3 among the three stages).

Moreover, lower SES was predictive of poorer colon cancer-specific survival regardless of sex (P < 0.001 for group 1 versus group 3 for both men and women) (Table 5). This was assessed through multivariate Cox regression model adjusted for age, race, side, and Dukes’ stage.

On the other hand, multivariate Cox regression model adjusted for age, sex, side, and Dukes’ stage was used to assess the impact of SES in each of the four principal race groups (white non-Hispanic, black non-Hispanic, Asian, and Hispanic). Lower SES index seems to be associated with worse survival in the four racial groups (Table 6).

Discussion

The current study evaluated the prognostic utility of SES on the outcomes of non-metastatic colon cancer patients. It showed a possible association between lower SES and worse colon cancer-specific survival. This association was consistent among the overall cohort of patients as well as among clinically defined patients’ subgroups (according to stage, side of the disease, sex, and race).

The results of the current study are similar to several previously published population-based analyses which confirmed the relationship between socioeconomic status and colon cancer patients’ outcomes [11, 12]. However, the current study is unique in relying upon on a dedicated database for socioeconomic information with the implementation of a standardized and validated tool for integrating all relevant dimensions for SES (compared to previous studies which relied on individual dimensions of SES in a non-standardized way). This adds considerable credibility to the results of the current analysis.

The current study cohort was restricted to non-metastatic patients. This is because the SEER database lacks enough details on the systemic therapy options (chemotherapy/targeted therapy) each patient has received in the metastatic setting. Thus, limiting the study participants to non-metastatic patients only was hoped to limit uncertainty in the current analysis. Likewise, the current cohort did not include rectal cancer patients. This is because of the lack of enough details about neoadjuvant (chemo)radiotherapy options that some patients might have received. Restriction to colon cancer patients treated with upfront surgery was done in the hope of limiting uncertainty in study results.

The current study has its own limitations that need to be addressed; first,there is generally a lack of information about comorbidity and performance status within the SEER database. This might have affected survival comparisons. However, it should be remembered that all patients included in the current study have undergone radical surgery to the primary tumor and regional lymph nodes. Thus, it is expected that most (if not all) of them have reasonable performance status and limited comorbidity at the time of diagnosis to be eligible for such a major surgery. Moreover, the primary endpoint of the current analysis is colon cancer-specific survival; thus, this should limit the potential confounding effect from lack of information about non-cancer mortality. Second, the current study is based on the information from the US healthcare system (which has its unique features and structure compared to other healthcare systems in other western countries as well as other world countries). Thus, the generalization of the results of the current analysis to other healthcare settings should be done with caution. Third, SEER database generally lacks technical details about non-surgical treatments (chemotherapy and radiotherapy). That is why (as clarified above) the inclusion of the current analysis was restricted to non-metastatic colon cancer patients to limit uncertainty.

These weaknesses need to be weighed against known strengths of the current analysis; most importantly the standardization of the assessment tools of SES and the reliance on the SEER database which is a high-quality population-based registry.

Possible reasons for survival differences based on SES might be related to the lack of access to timely cancer care among people with lower SES; moreover, lower educational status and awareness among less educated people might lead to a delay in presentation to healthcare workers and subsequent presentation at a more advanced disease stage. Lower education might also be liked to a lower compliance with the recommended treatment [13].

The findings of the current study highlight the major role played by socioeconomic factors in determining the outcomes of cancer patients in general and colon cancer patients in particular. Despite the accumulating body of evidence highlighting the role of SES in determining cancer outcomes, this dimension is frequently overlooked by treating physicians which might affect the quality of care provided to cancer patients. There is a need to increase the awareness of healthcare workers dealing with cancer patients about the importance of SES and to integrate this into their training curricula. The results of the current analysis also highlight the importance of reducing disparities in healthcare services. This will hopefully improve the outcomes of socially disadvantaged groups of cancer patients.

Outcomes of non-Hispanic black patients with colon cancer have been reported to be poorer than non-Hispanic white patients in a number of population-based studies [14, 15]. This has been previously ascribed partially to SES differences. The current study does not support this explanation (given the non-significant interaction testing between race and SES).

Within multivariate Cox regression analysis among different racial groups, lower SES index was associated with worse survival in the four racial groups and the impact seems to be more pronounced among white Americans compared to other racial groups. This observation might be because of the fact that white Americans represents 70% of the total study cohort; thus, it is more likely for SES differences to demonstrate statistical significance in this subgroup compared to other racial subgroups.

In conclusion, lower SES is associated with worse colon cancer-specific survival among non-metastatic colon cancer patients. Further studies are needed to dissect the mechanisms linking SES with cancer outcomes.

References

Clegg LX, Reichman ME, Miller BA et al (2009) Impact of socioeconomic status on cancer incidence and stage at diagnosis: selected findings from the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results: National Longitudinal Mortality Study. Cancer Causes Control CCC 20(4):417–435

Link BG, Phelan JC (1996) Understanding sociodemographic differences in health–the role of fundamental social causes. Am J Public Health 86(4):471–473

Stover GN (2009) Social conditions and health. Am J Public Health 99(8):1355

Zhang Q, Wang Y, Hu H et al (2017) Impact of socioeconomic status on survival of colorectal cancer patients. Oncotarget 8(62):106121–106131

Manser CN, Bauerfeind P (2014) Impact of socioeconomic status on incidence, mortality, and survival of colorectal cancer patients: a systematic review. Gastrointest Endosc 80(1):42–60.e9

Yost K, Perkins C, Cohen R et al (2001) Socioeconomic status and breast cancer incidence in California for different race/ethnic groups. Cancer Causes Control 12(8):703–711

Yu M, Tatalovich Z, Gibson JT et al (2014) Using a composite index of socioeconomic status to investigate health disparities while protecting the confidentiality of cancer registry data. Cancer Causes Control 25(1):81–92

Liu L, Deapen D, Bernstein L (1998) Socioeconomic status and cancers of the female breast and reproductive organs: a comparison across racial/ethnic populations in Los Angeles County, California (United States). Cancer Causes Control 9(4):369–380

https://seer.cancer.gov/seerstat/databases/census-tract/index.html. Last accessed 24 Feb 2019

Venook AP, Niedzwiecki D, Innocenti F, et al. Impact of primary (1º) tumor location on overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) in patients (pts) with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC): Analysis of CALGB/SWOG 80405 (Alliance). Am Soc Clin Oncol 2016.

Ciccone G, Prastaro C, Ivaldi C et al (2000) Access to hospital care, clinical stage and survival from colorectal cancer according to socio-economic status. Ann Oncol 11(9):1201–1204

Barclay KL, Goh PJ, Jackson TJ (2015) Socio-economic disadvantage and demographics as factors in stage of colorectal cancer presentation and survival. ANZ J Surg 85(3):135–139

Tourangeau A, Puts MTE, Tu HA et al (2013) Factors influencing adherence to cancer treatment in older adults with cancer: a systematic review. Ann Oncol 25(3):564–577

Tawk R, Abner A, Ashford A et al (2015) Differences in colorectal cancer outcomes by race and insurance. Int J Environ Res Public Health 13(1):48

Polite BN, Dignam JJ, Olopade OI (2005) Colorectal cancer and race: understanding the differences in outcomes between African Americans and whites. Med Clin N Am 89(4):771–793

Acknowledgements

This study is based on the NCI-SEER specialized database for census-tract level SES data.

Funding

This study was not funded.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

No author has any conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. As this study is based on a publicly available dataset, IRB approval was not required for it.

Informed consent

As this study is based on a publicly available database without identifying patient information, informed consent was not needed.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

About this article

Cite this article

Abdel-Rahman, O. Outcomes of non-metastatic colon cancer patients in relationship to socioeconomic status: an analysis of SEER census tract-level socioeconomic database. Int J Clin Oncol 24, 1582–1587 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10147-019-01497-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10147-019-01497-9