Abstract

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy has become the preferred method of treatment of cholelithiasis since its inception in 1987. Although overall complication rate is less than that of traditional approach, two operative complications of laparoscopic cholecystectomy have been frequently described in the literature. One is the bile duct injury or leak and the other one spillage of stones resulting in delayed abscess formation (Horton and Florence, Am J Surg 175:375–379, 1998; Frola et al., BJR 72:201–203, 1999). The incidence of abscess is very rare (approximately 0.3%). The location of the subsequent abscess and the inflammatory masses containing stones or stone fragments is generally in the abdominal wall, subhepatic space, or the retroperitoneum below the subhepatic space but can occur anywhere in the abdomen, right thorax, at trocar site, and at incisional hernia (Zehetner et al., Am J Surg 193:73–78, 2007; Offiah et al., BJR 75:393–394, 2002; Morrin et al., AJR 174:1441–1445, 2000). We report here a case of abscess formation due to spilled stone occurring 6 months post-laparoscopic-cholecystectomy. The diagnosis was suggested by ultrasound examination and was further confirmed by computed tomography scan of the abdomen.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Case report

A young 22-year-old Arab female was referred to us for ultrasound examination with history of pain and swelling in right lumbar region. She had a history of laparoscopic cholecystectomy about 6 months back. On clinical examination, there was mild tenderness at the site of swelling and mild right hypochondrial tenderness. There was no organomegaly on examination.

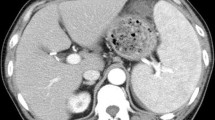

Her ultrasound examination (Fig. 1) revealed a thick septate collection in posterolateral subhepatic space extending through the intercostals region to the subcutaneous planes of posterior abdominal wall. Multiple round hyperechoic foci with acoustic shadowing were noted within the collection. A computed tomography (CT) scan of upper abdomen (Fig. 2) was performed which showed the extension of collection better and revealed a metallic density clip suggesting the possibility of surgical clip and multiple hyperdense foci at the dependent portion within the collection.

Discussion

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy introduced by Philip Lyon of France in 1987 has become one of the major therapeutic innovations of recent times for treatment of gallbladder disease. The overall morbidity of laparoscopic cholecystectomy is between 2% and 11%, which compares favorably well with an incidence of 4% to 6% for elective cholecystectomy [1, 2].

This new method of access for an old operation is associated with new complication such as trocar injuries and increased incidence of some existing complications. The added risk of gallbladder perforation leading to bile and gallstone spilling is more common during laparoscopic cholecystectomy than during open cholecystectomy, incidence of spilled gall stones after laparoscopic cholecystectomy being 5.4% to 19% [3]. Stone spilled during open cholecystectomy can be retrieved easily either by mopping up with a sponge or irrigation and aspiration with a large bore suction which is difficult in laparoscopic cholecystectomy [1, 2, 4].

Spilled stones or stone fragments can lodge virtually in any crevices of abdominal cavity and may result in a range of complications. In general, the complications because of lost gallstones in laparoscopic cholecystectomy are infrequent, occurring in approximately 1.7 per 1,000 laparoscopic cholecystectomies [5], which makes diagnosis difficult if the complication occurs late. A recent study by Zehenter et al. [3] has listed all possible complications resulting from spilled gallstones or lost gall stones after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The most common complication is abscess in the abdominal wall followed by intra-abdominal abscess usually in subhepatic space or retroperitoneum inferior to subhepatic space as noted in our case [3]. Other complications include fistula formation of all different kinds ranging from fistulas of the skin to fistulas of the gluteolumbar region. Some other rare complications which have been reported include stone expectoration, stones in a hernia sac, stones in ovary, and also tubalithiasis [3]. Stone may erode into the wall of the transverse colon and sometimes can migrate into the pleural space. This variability is because of pneumoperitoneum and irrigation during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Infective complication due to spilled stones is more likely to occur in setting of acute cholecystitis, the incidence being 0.1% to 0.3% and it has been reported to occur often very late after surgery. The reported mean duration for development of abscess ranges from 4 months to 10 years after laparoscopic cholecystectomy [6, 7]. The diagnosis of spilled stones should be considered when an abscess or fistula formation occurs years after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The radiologist should be aware that this complication is not limited to immediate postoperative period but may occur much later [4, 8, 9]. Cross-sectional imaging ultrasound and CT scan is helpful in demonstrating collection-containing calculus, which is essential to make the diagnosis. Both of these modalities can also be used to guide the percutaneous drainage. Identification of calculus is essential as it is the source of infection and retrieval is essential to control the infection. Abscess formation after spilled gall stones can be treated by the retrieval of lost gallstones, as well as drainage or rinsing of abscess cavities, by an open approach [3] or by interventional [10], laparoscopic [11], and thoracoscopic approach. Percutaneous extraction by an interventional radiologist can be considered as an alternative to surgery [12].

References

Horton M, Florence G (1998) Unusual abscess pattern following dropped gallstones during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Am J Surg 175:375–379

Frola C, Cannici F, Cantoni S, Tagliafico E, Luminati T (1999) Peritoneal abscess formation as a late complication of gallstone spilled during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. BJR 72:201–203

Zehetner J, Shamiyeh A, Wayand W (2007) Lost gallstones in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: all possible complications. Am J Surg 193:73–78

Offiah C, Robinson P, Keeling-Roberts CS (2002) The one that got away. BJR 75:393–394

Woodfield JC, Rodgers M, Windsor JA (2004) Peritoneal gallstones following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: incidence, complications, and management. Surg Endosc 18:1200–1207

Morrin M, Kruskal J, Saldinger P, Kane R (2000) Radiological features of complication arising from dropped gallstone in laparoscopic cholecystectomy patients. AJR 174:1441–1445

Van Brunt PH, Lanzafame RJ (1994) Subhepatic inflammatory mass after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a delayed complication of spilled gallstone. Arch Surg 129:882–893

McGanan JP, Stein M (1995) Complication of laparoscopic cholecystectomy: imaging and intervention. AJR 165:1089–1097

Mahale A, Hegde V, Shetty R, Venugopal A, Kumar A (2001) Dropped calculus post laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Indian J Radiol Imaging 11(2):81–82

Whiting J, Welch NT, Hallissey MT (1997) Subphrenic abscess caused by gallstones “lost” at laparoscopic cholecystectomy one year previously: management by minimally invasive techniques. Surg Laparosc Endosc 7:77–78

Kelkar AP, Kocher HM, Makar AA, Patel AG (2001) Extraction of retained gallstones from an abscess cavity: a percutaneous endoscopic technique. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 11:129–130

Trerotola SO, Lillemoe KD, Malloy PC, Osterman FA Jr (1993) Percutaneous removal of “dropped” gallstones after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Radiology 188:419–421

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Khalid, M., Rashid, M. Gallstone abscess: a delayed complication of spilled gallstone after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Emerg Radiol 16, 227–229 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10140-008-0730-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10140-008-0730-5