Abstract

The warming climate results in higher losses in potato production, storage and processing, especially in developing countries. Feeding, anaerobic fermentation, combustion, composting and charring of potato peels with reject potatoes were analyzed on a pilot scale. It was revealed that feeding is the most promising alternative; however, additional energy inputs for potato waste steaming are advisable to break down trypsin inhibitors that naturally decrease protein digestibility. Other results indicate that it is advisable to ferment the slurry obtained with post-harvest residues into biogas and subsequently pyrolyze dewatered fermentation residues into biochar. It is appropriate to subsequently enrich the biochar by the liquid fraction of fermentation residues via filtration. Enough indications was found that this setup provides multiple horizontal synergies as well as parallel synergies, both technical and economic, that altogether create prerequisites for sustainability of developing agriculture.

Graphic abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Many communities in the developing world are highly dependent on potato production, both economically and nutritionally (Scott et al. 2019). Potatoes provide a high food production value per unit area, and their tubers are rich in vitamin C, niacin and vitamin B6 (Mohammadi et al. 2008). Nevertheless, the potato plant has one of the heaviest production demands for fertilizer inputs, the price of which has been rising in the long term (Khabarov and Obersteiner 2017). As predicted by Scott et al. (2000) and independently by Hijmans (2003), the potato market is becoming increasingly volatile under climate change as the currently bred varieties suffer from low heat tolerance (Willersinn et al. 2017), which negatively affects the tuberization period (Honma and Yamakawa 2019), resistance to droughts (Qin et al. 2019), immunity to pests (Gao 2018) and storage (Fehres and Linkies 2018). As it takes a long time to develop new potato cultivars accustomed to warm temperatures (Tillault and Yevtushenko 2019), it is expected that losses in production and storage will increase (Fehres and Linkies 2018). There used to be a broad consensus in the potato industry that damaged tubers, peels, slivers and gray starch comprise some 70% of all the potato processing waste, which accounts for approximately 4% of the harvest (Osawa et al. 2018). Nevertheless, the amount of potato waste has almost doubled over the last decade and continues to rise steeply, especially in the developing countries which cannot afford cooled warehouses (Hadizadeh et al. 2019). The established schema in potato waste management is as follows: prevention (Zarzecka and Gugała 2018); food (Scott et al. 2019); feed (Duynisveld and Charmley 2018); fine chemicals and materials (Arapoglou et al. 2010); biogas production (Antwi et al. 2017); composting (Ghinea et al. 2019); landfilling (Parawira et al. 2004). However, developing countries cannot afford the demanding steps of this cascade, in particular the starch refining technologies (Dupuis and Liu 2019) capable of turning potato biowaste into bioplastics (Kasmuri and Zait 2018) wallpaper glue (Zhang et al. 2019) or drilling mud (Wang et al. 2015). Plowing into arable land should also be phased out to prevent pests (Gao 2018). On the other hand, the climate of many developing countries allows the drying of potato waste and its subsequent energy use, both by incineration and pyrolysis (Mardoyan and Braun 2015).

An environmentally friendly and technologically undemanding solution for potato waste management which would be financially viable under the volatile conditions of developing economies is yet to be found (Hadizadeh et al. 2019). As regards anaerobic fermentation, the revenues come from biogas or electricity sale and subsequent agronomic benefits (nutrients and organic matter recovery) following the application of fermentation residues into arable land (Maroušek et al. 2018). As for combustion, the revenues come from energy production and nutrients present in the ash (Vochozka et al. 2016a). The pricing of compost is based on the accessible nutrients (Rigby et al. 2016) and the quality of organic matter (Kolář et al. 2011). As for charring, the valuation considers the energy stored in charcoal (Mardoyan and Braun 2015) or the price of the biochar obtained. (This involves the nutrients present and other soil improving properties (Maroušek et al. 2019)). However, from an economic point of view, it needs to be pointed out that nutrients in organic matter must first be mineralized via soil biota before they can be used for plant nutrition (Stehel et al. 2018). Developing countries are characterized not only by low labor efficiency but also by high currency volatility (Hašková 2017); therefore, optimal technology setup should take into account the state of the market in more developing countries.

Following the above, it can be summarized that the amount of potato waste is soaring in the developing world and further rise is to be expected. Outdated waste management methods that are followed by inappropriate agronomic practices support the transmission of pests, endanger soil structure and transform some of the nutrients into chemical forms that are not acceptable by crops, altogether further increasing environmental and economic damage. Given that the high acquisition costs prevent the deployment of modern biorefining technologies, an economically undemanding solution is urgently in demand.

The objective of the paper is to perform a techno-economic analysis of potato waste utilization methods in developing economies and to recommend a solution that will improve farming performance (nutrient recovery and soil quality in particular).

Methodology

Material

Raw potatoes (Santana, mid-to-late variety) and its peels with reject tubers (A) were obtained from a local producer of frozen potato products (Friall s.r.o., Czech Republic) and stored at 4 °C until analyzed or processed. A series of 3 automatic 160-L potato steamers (AGRAFA s.r.o., Czech Republic) was used to steam potatoes for 6 h according to the manufacturer’s manual. With regard to the biochemical characteristics (Table 1), volatile solids (VS, %) were analyzed using the U.S. EPA (2001) method 1684 (biosolids analysis); pH and biological oxygen dement (BOD, mgL–1) were measured using the HQ40D portable pH and BOD meter (Hach Lange GmbH, Germany); an analysis of hot water extractable carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus (HWC, HWN and HWP, %) was carried out according to Kolář et al. (2008) in modification by Maroušek et al. (2014); starch and ash (%) were determined according to Arapoglou et al. (2010); fat (%) was quantified using 99.9% hexane and the Soxhlet extractor (Wako Pure Chemicals Ltd., Japan). The labile (L) and resistant (R) fractions of organic matter were analyzed via the sulfur acid method as modified by Rovira and Vallejo (2007) using the NC–90A automatic high-sensitive N/C analyzer (Shimadzu Inc., Japan).

Feeding

An in vivo trial was conducted in 3 groups of 10 piglets (Pietrain type, 3–4 months old, 32.9 ± 6.5 kg weight, healthy) for 50 days. All groups were supplied with an unlimited amount of water and feed mixture proportional to maintaining their necessary development and growth. The first group served as a control sample; the second and third were provided every day with extra potato peels and reject potatoes (raw and steamed) ad libitum. Their average daily gain (ADG) was measured using FORMATIC 7D tensometric scales (FORMAT1, Czech Republic). Blood biochemical analyses were carried out on a daily basis, including analyses on packed cell volume (PCV); hemoglobin (HM); total protein (TPR); albumin (AL); creatinine (CR); blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and cholesterol (CH) levels according to Škapa and Vochozka (2019). Metabolizable energy for pigs (MEp) was analyzed (and calculated) in vitro according to May and Bell (1971).

Anaerobic fermentation

Potato waste (raw potatoes for comparison) was mixed with 1% (VS) of inoculate (B) that was obtained from the Nedvědice biogas station (Czech Republic, technology design and corresponding processing parameters of the biogas station as well as feedstock properties stated in Maroušek et al. 2018). Subsequently, the inoculated biowaste was subjected to a battery of S2 automatically operated semi-continuous anaerobic reactors (Stix Ltd., Czech Republic). The biogas yields obtained were monitored by the GA3000 infrared-based biogas analyzer (Chromservis Ltd., Praha, Czech Republic), and the cumulative production of methane was converted to 20 °C and atmospheric pressure (101.3 kPa).

Combustion

The heating value of sun-dried potato waste was measured using the auto-calculating bomb calorimeter (CA–4AJ, Shimadzu, Japan). European standards for solid biofuels were used to assess fuel specifications; see Mardoyan and Braun (2015) for details.

Composting

Composting was carried out in two steps: First, the raw feedstock was prepared. The feedstock (VS) included grass clippings (30%), rye straw (30%) and sunflower stalks (40%), altogether 42.6 tonnes. 1.6-meter high and 3-meter wide rows (21.3 tonnes each) were tossed by a tractor-carried mobile compost turner every two weeks for six months. Subsequently, one of the rows was enriched with 21.3 tonnes of potato waste (50% VS), and composting was performed for another six months (both samples). The experiment was concluded by carrying out analyses on cation exchange capacity (CEC); base saturation (BS); total porosity (TP); air-filled porosity (AFP); water retention (WR) and basal respiration (BR).

Charring

The potato waste was mechanically dewatered using the 2SS-PHX double-screw continuous dewatering press (PHARMIX, s.r.o, Czech Republic) tailored to achieve continuous backpressure tension of 400 N. This pressure dewatered the biowaste to some 78% VS. The dewatered potato waste was subjected to the continuous (150 kg h–1) standardized UHL-07 pyrolysis unit (Aivotec, s.r.o., Czech Republic). In brief, the pyrolyzing apparatus consists of the entrance hopper equipped with an inner vertical slow motion helix. The slowly rotating helix continuously compresses the biowaste down into the mechanical turnstile located at the bottom of the hopper. The turnstile provides minimum air leakage to minimize combustion and the related ash formation. The turnstile leads to the pyrolysis chamber made up of a thick–walled refractory horizontal wide cylinder, where the material is exposed to the external source of heat (for more construction details see Mardoyan and Braun 2015). The potato biowaste was pyrolyzed at 350 °C. (The speed of the horizontal helix responsible for the hydraulic retention time was set to 0.5 Hz, which corresponds to the delay of the feedstock in the pyrolysis chamber for approximately 8 min.)

Agrochemical value

Pig slurry, fermentation residues, ash, compost and biochar were analyzed for L and available nutrients (according to Rigby et al. 2016 as follows: the sum of mineral and potentially mineralizable nitrogen (Nmin + PMN); hot water extractable phosphorus (HWP) and hot water extractable potassium (HWK)). The presence of heavy metals was analyzed using the AAnalyst 700 atomic absorption spectrometer (PerkinElmer Inc., USA) with a continuum deuterium background corrector and HGA 900 Graphite Furnace. (All measurements were carried out in an airy acetylene flame.) The potential toxic effects of inhibitors were analyzed by cress, barley and salad germination tests based on the International Standards Organization’s standards for biotoxicity test procedures adapted according to Busch et al. (2012). Gas chromatography and mass spectrometry analyses on polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, dioxins and furans were performed externally (AGRO–LA, spol. s.r.o., Czech Republic) according to Fabbri et al. (2013). The agrochemical value of the organic matter was determined by its biodegradability (ratio of labile and recalcitrance organic matter, hereinafter as L/R), as described in Kolář et al. (2008). Microporosity (BET) was detected using the technique of helium adsorption via the TriStar 3000 surface area analyzer (Micromeritics Ltd., Japan) after 48 h of degassing at 200 °C and 1 h of degassing at 300 °C.

Financial assessment

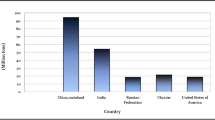

Payback period (PP, according to Hašková 2017) is calculated to indicate unrealistically long investments). Net present value (NPV, according to Hašková 2017) was calculated to subsequently indicate the most attractive investment opportunity. With regard to feeding (I.), the financial analysis considered the running cost (steaming is 10% more costly), purchase cost of the steaming technology (1 k USD) and the revenues from meat sale and slurry valuation. As far as the anaerobic fermentation (II.), increased running cost (+ 70%), acquisition cost of the 0.3 MW biogas station (0.4 M USD), revenues coming from electricity sale and agrochemical valuation of the fermentation residues were taken into account. Calculation on combustion (III.) considered the acquisition cost of the furnace (10 k USD) and incomes from energy production and the agrochemical value of the ash obtained. With regard to composting (IV.), the increase in cost is negligible and calculation considered in particular pricing of the product. Regarding production of char (V.), revenues from its sale and the cost of the pyrolysis apparatus (20 k USD) were taken into account. In addition to V., calculation on biochar (VI.) included also additional cost of the filtration technology (5 k USD). Calculations were carried out under economy of 5 different developing countries (Armenia, Georgia, India, Botswana and Vietnam), whereas the results represent average values. All experiments were carried out with 10 repetitions (n = 10) unless stated otherwise; zunzun.com was used for graphic processing.

Results and discussion

The characteristics of the potato waste (Table 1) used are similar to reports found in the literature (Parawira et al. 2004), which is a good prerequisite for subsequent generalization. Heavy metals as well as the most common inhibitors (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, dioxins and furans) in all of the measurements were far below the limits required in the USA and EU (data not stated). This is indirectly confirmed by analysis on cress, barley or salad germination, none of which showed any sign of phytotoxicity. The high proportion of L in the biowaste makes it possible to predict that all available nutrients will be readily available to both animals and soil biota. Given the HWC/WHN is close to 2, it can be assumed that the fermentation processes will be stable (Maroušek et al. 2014).

With regard to feeding experiments, it can be stated that both raw and steamed potato wastes showed minimal changes or slight improvements as far as the blood response (Table 2). This is in line with the literature, as it has been repeatedly reported that potatoes can be a source of nutritionally important factors like vitamin A, ascorbic acid, thiamin, riboflavin or niacin (Mohammadi et al. 2008). All animals remained in good shape during the experiments, and their autopsy showed no sign of anomalies. Feeding with steamed potato waste significantly increased the ADG (+ 6.3%). Regarding the raw potatoes diet, the change on average ADG was lower (+ 1.4%). Food weighing showed that the cooked potatoes had higher palatability (approximately 4 times higher consumption compared to raw potatoes). With an acceptable level of simplification, measurements revealed that 8.2 ± 4.4 kg of steamed potato waste resulted in 1 kg of live weight, while 15.9 ± 8.3 kg of raw biowaste was needed to achieve the same.

Both of these findings are in good agreement with Tuśnio et al. (2011), who concluded that a potato diet did not show beneficial health effects on lipid metabolism, but did correlate with an increase in ADG. It is assumed that a low response toward feeding with raw potato waste can be seen in the presence of trypsin inhibitors, as these are capable of decreasing protein digestibility in the rest of the feed. The analysis of MEp showed almost identical values for raw and steamed biowaste (11.7 ± 0.4 MJ kg–1 and 11.6 ± 0.4 MJ kg–1). Following the above, it can be argued that the in vitro MEp method is incapable of delivering results comparable to in vivo trials, since it does not adequately respect the complexity of the digestive system (May and Bell 1971). In agreement with Thu et al. (2012), the agrochemical valuation of pig slurry confirms that this material is rich in L that can quickly act as an energy source for soil biota. On the other hand, it contains high levels of water (88%) and the availability of nutrients for plant production is low since these are present mostly in organic forms that are unavailable to plant intake (Table 3) and tend to be lost in the form of ammonia emissions.

Taking into account the value of nutrients on the fertilizer market (Kim et al. 2019), the fertilizing value of 1 metric ton of potato waste (fresh weight) that was turned into slurry by pigs can be priced for some 20 USD. Regarding the valuation of the organic matter, its price was calculated by lowering the price of manure (considered to be an example of easily degradable organic matter, Kolář et al. 2011) by its nutrient levels (10 USD t–1 L). Following the above, the benefits of feeding, which include pork production, nutrients and the organic matter present in the slurry obtained, are stated in Table 5. With regard to biogas production (Fig. 1), it can be seen that at the beginning, steamed potato waste ferments slightly faster than raw potatoes. (The lag phase appears to be one day shorter.) Given that raw potato waste delivered slightly higher (48.6 ± 1.3) levels of carbon dioxide in comparison with raw potatoes (46.0 ± 1.7) during the lag phase, it can be assumed that spontaneous consortia of microorganisms present in the raw biowaste are partly sterilized during steaming.

For this reason, inoculation with active colonies of anaerobic microorganisms is advisable. After about 3 weeks, however, even these slight differences disappear and the total methane production per metric ton in fresh weight stabilizes itself in the close neighborhood of 67 m3 in both cases (price equivalent to 37.2 kg of potatoes or 6.5 kg of pork under developing economy). With regard to the feedstock BOD, it can be stated that almost 85% of the theoretical methane yield was achieved and further production cannot be expected within a commercially reasonable period. Analogical methane yields were obtained more slowly than as reported by Achinas et al. (2019) or Parawira et al. (2004); nevertheless, it should be noted that their performance was achieved with the help of energy-intensive disintegration techniques and costly reactors, or, more precisely, with the help of costly enzymatic mixtures.

Antwi et al. (2017) also reported their methane yields as occurring faster; however, their methods considered pure potato starch. The analysis confirmed that the level of L present in the fermentation residues is low (Table 3). This reveals that (1) the process parameters of the anaerobic fermentation experiment were set up well and the methanogenesis approached a techno-economic optimum (Maroušek et al. 2018) and (2) there is no other L left in the feedstock (compared to Fig. 1). Following the levels of nutrients detected in the fermentation residues (Table 3) and the current prices on the market of fertilizers (Kim et al. 2019), the fertilizing value of 1 metric ton of potato waste turned into fermentation residues is quite low, since the nutrients are present mostly in organic forms. The price of organic matter is also low, since majority of L was fermented into methane.

Revenues linked to the anaerobic fermentation of biowaste and its subsequent application into arable land are provided in Table 5. Regarding combustion, the heating value of the sun-dried potato waste turned out to be 16.39 MJ kg–1. Energy price of 1 tonnes of this biowaste is equal to 2.4 kg of pork or 15.1 kg of potatoes. Parawira et al. (2004) reported similar values (16.4 MJ kg–1). The agrochemical value of the ash obtained from 1 ton of fresh potato waste is high (Table 3); however, its quantity is low. As regards composting, it can be seen (Table 4) that CEC was not improved by the incorporation of potato waste. However, it can be assumed that this key feature might begin to increase if the experiment is run for a longer period of time, because to achieve increased CEC, merely decomposting the organic matter insufficient; the humification process should also begin (Kolář et al. 2011). Other biochemical indicators of compost quality increased, confirming that the proportion of L has managed to supply energy to the consortia of aerobic biota present. In particular, the WR was significantly increased (Table 4). This is indirectly confirmed by the analysis of nutrients available for plant nutrition, presented in Table 3.

Data on nutrient bioavailability also indicate that the aerobic consortia of microorganisms were not limited in their metabolic processes. It should be reflected that the agrochemical properties (Table 4) are not sufficient to evaluate compost pricing because of the high cost related to the logistics of its application into arable land. For that reason, comparison with competing products has to be taken into account (20 USD t–1). As far as charring of biowaste is concerned, the heating value of the char showed to be 26.52 ± 0.3 MJ kg–1 which, taking into account the losses (gaseous and liquid products) and char prices on global market (Mardoyan and Braun 2015), means that 1 ton of charred potato waste can be valued for 540 USD t–1 (Table 5). With regard to the biochar (dust fraction) obtained from potato waste, it showed out that its fertilization value (Table 3) could be more than doubled when using the filtration technique. However, it is not only the levels of nutrients that define biochar valuation (Vochozka et al. 2016b). Biochar did not show any sign of phytotoxicity to cress, barley or salad germination.

Heavy metals in all of the tests stayed far below the limits required in the USA and EU (data not stated). It can be argued that biochar properties (pH = 8.7 ± 0.1; CEC = 22.4 ± 0.0 cmolc kg–1; BET = 45.7 ± 9.1 m2g–1) are of moderate quality (Fabbri et al. 2013). In agreement with Vochozka et al. (2016b), such biochar can be priced as 720 USD t–1 (Table 5). Following the above, it was proposed to setup the technology as stated in the Graphical Abstract. Estimated payback period is stated in Table 5.

Conclusions

Rising temperatures sharply increase potato waste quantity in developing countries. However, developing countries cannot implement modern prevention and waste management technologies since these are capital-intensive. Affordable technologies (steaming, feeding, anaerobic fermentation, combustion, composting, charring and combinations thereof) to process potato waste were biotechnologically (recovery of organic matter, nutrients and energy) and financially assessed in consideration of the limitations of developing economies. A sufficient number of indications were obtained to suggest that the setup that is depicted in the Graphical Abstract (description follows) is the closest to the techno-economic optimum under the given conditions.

Potato waste is steamed and used as feed for pigs. Pig slurry and potato waste that pigs refused to consume are anaerobically fermented, whereas the biogas obtained is combusted to generate electricity and heat. The heat from biogas combustion runs the pyrolysis of the fermentation residues; the heat from the pyrolysis reactor runs the steaming chamber. Subsequently, the charred fermentation residues are turned into nutrient-enriched biochar by serving as a filter through which the liquid fraction of fermentation residues is poured.

Provided that the potato waste management is carried out according to the above, multiple synergies can be achieved. At first, steaming of the potato waste breaks down trypsin inhibitors responsible for limited protein digestibility. This results in improved animal health (case study showed significant improvement of blood results, in particular + 4.7% PCV, + 4.1% HM and + 5.7% CH) that is linked with higher feed intake (+ 6.3% ADG), which leads to an improved economy of pig production in general. Secondly, steamed and digested potato waste accelerates anaerobic fermentation and the higher amounts of electricity from biogas combustion also increase the income. Thirdly, the cascade of steaming, anaerobic fermentation and pyrolysis blocks the transfer of disease vectors and pests (including mycotoxins) back to the arable land. Last but not least, production and subsequent application of nutrient-enriched biochar into arable land results in multiple improvements in soil quality. (Case study showed + 15.9% WR and + 11.5% BR.) These indicators can be interpreted not only as another source of additional revenues from subsequent crop production, but also as a tool to mitigate the risks of financial losses related to drought and heavy rains (erosion and nutrient leaching). Fifth, more efficient nutrient recovery (case study revealed + 22.8% WHP and + 19.6% HWK) can be achieved, which significantly reduces fertilizer spending. However, a vast majority of nitrogen is lost during pyrolysis step. This is not a momentous problem at the current nitrogen pricing; however, further research should be devoted to incorporate a undemanding nitrogen recovery process.

Abbreviations

- ADG:

-

Average daily gain

- AFP:

-

Air-filled porosity

- AL:

-

Albumin

- BET:

-

Microporosity

- BOD:

-

Biological organic demand

- BR:

-

Basal respiration

- BS:

-

Base saturation

- BUN:

-

Blood urea nitrogen

- CEC:

-

Cation exchange capacity

- CH:

-

Cholesterol

- CR:

-

Creatinine

- HM:

-

Hemoglobin

- HWC:

-

Hot water extractable carbon

- HWN:

-

Hot water extractable nitrogen

- HWP:

-

Hot water extractable phosphorus

- L:

-

Labile fraction of organic matter

- MEp:

-

Metabolizable energy for pigs

- Nmin:

-

Mineral nitrogen

- PCV:

-

Packed cell volume

- PMN:

-

Potentially mineralizable nitrogen

- R:

-

Resistant fraction of organic matter

- TP:

-

Total porosity

- TPR:

-

Total protein

- VS:

-

Volatile solids

- WR:

-

Water retention

References

Achinas S, Li Y, Achinas V, Euverink GJW (2019) Biogas potential from the anaerobic digestion of potato peels: process performance and kinetics evaluation. Energies 12(12):2311. https://doi.org/10.3390/en12122311

Antwi P, Li J, Boadi PO, Meng J, Shi E, Deng K, Bondinuba FK (2017) Estimation of biogas and methane yields in an UASB treating potato starch processing wastewater with backpropagation artificial neural network. Bioresour Technol 228:106–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2016.12.045

Arapoglou D, Varzakas T, Vlyssides A, Israilides C (2010) Ethanol production from potato peel waste (PPW). Waste Manage 30(10):1898–1902. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2010.04.017

Busch D, Kammann C, Grünhage L, Müller C (2012) Simple biotoxicity tests for evaluation of carbonaceous soil additives: establishment and reproducibility of four test procedures. J Environ Qual 41(4):1023–1032. https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq2011.0122

Dupuis JH, Liu Q (2019) Potato starch: a review of physicochemical, functional and nutritional properties. Am J Potato Res 96(2):127–138. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12230-018-09696-2

Duynisveld JL, Charmley E (2018) Potato processing waste in beef finishing diets; effects on performance, carcass and meat quality. Anim Prod Sci 58(3):546–552. https://doi.org/10.1071/AN16233

Fabbri D, Rombolà AG, Torri C, Spokas KA (2013) Determination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in biochar and biochar amended soil. J Anal Appl Pyrol 103:60–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaap.2012.10.003

Fehres H, Linkies A (2018) A mechanized two–step cleaning and disinfection process strongly minimizes pathogen contamination on wooden potato storage boxes. Crop Prot 103:111–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cropro.2017.09.016

Gao Y (2018) Potato tuberworm: impact and methods for control–mini review. CAB Rev 13(022):1–3. https://doi.org/10.1079/PAVSNNR201813022

Ghinea C, Apostol LC, Prisacaru AE, Leahu A (2019) Development of a model for food waste composting. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 26(4):4056–4069. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-018-3939-1

Hadizadeh I, Peivastegan B, Hannukkala A, van der Wolf JM, Nissinen R, Pirhonen M (2019) Biological control of potato soft rot caused by Dickeya solani and the survival of bacterial antagonists under cold storage conditions. Plant Pathol 68:297–311. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppa.12956

Hašková S (2017) Holistic assessment and ethical disputation on a new trend in solid biofuels. Sci Eng Ethics 23(2):509–519. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-016-9790-1

Hijmans RJ (2003) The effect of climate change on global potato production. Am J Potato Res 80:271–279. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02855363

Honma Y, Yamakawa T (2019) High expression of GUS activities in sweet potato storage roots by sucrose–inducible minimal promoter. Plant Cell Rep 38(11):1417–1426. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00299-019-02453-7

Kasmuri N, Zait MSA (2018) Enhancement of bio–plastic using eggshells and chitosan on potato starch based. Int J Eng Technol 7(3):110–115. https://doi.org/10.14419/ijet.v7i3.32.18408

Khabarov N, Obersteiner M (2017) Global phosphorus fertilizer market and national policies: a case study revisiting the 2008 price peak. Front Nutr 4:22. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2017.00022

Kim SJ, Sohngen B, Sam AG (2019) The implications of weather, nutrient prices, and other factors on nutrient concentrations in agricultural watersheds. Sci Total Environ 650:1083–1100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.09.012

Kolář L, Kužel S, Peterka J, Štindl P, Plát V (2008) Agrochemical value of organic matter of fermenter wastes in biogas production. Plant Soil Environ 54:321–328. https://doi.org/10.17221/412-PSE

Kolář L, Kužel S, Peterka J, Borová-Batt J (2011) Utilisation of waste from digesters for biogas production. Biofuels engineering process technology. InTech, New York, pp 191–220

Mardoyan A, Braun P (2015) Analysis of Czech subsidies for solid biofuels. Int J Green Energy 12:405–408. https://doi.org/10.1080/15435075.2013.841163

Maroušek J, Hašková S, Zeman R, Váchal J, Vaníčková R (2014) Nutrient management in processing of steam-exploded lignocellulose phytomass. Chem Eng Technol 37:1945–1948. https://doi.org/10.1002/ceat.201400341

Maroušek J, Stehel V, Vochozka M, Maroušková A, Kolář L (2018) Postponing of the intracellular disintegration step improves efficiency of phytomass processing. J Clean Prod 199:173–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.07.183

Maroušek J, Strunecký O, Stehel V (2019) Biochar farming: defining economically perspective applications. Clean Technol Environ 7:1389–1395. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10098-019-01728-7

May RW, Bell JM (1971) Digestible and metabolizable energy values of some feeds for the growing pig. Can J Anim Sci 51:271–278. https://doi.org/10.4141/cjas71-040

Mohammadi A, Tabatabaeefar A, Shahin S, Rafiee S, Keyhani A (2008) Energy use and economical analysis of potato production in Iran a case study: Ardabil province. Energ Convers Manage 49:3566–3570. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2008.07.003

Osawa H, Akino S, Araki H, Asano K, Kondo N (2018) Effects of harvest injuries on storage rot of potato tubers infected with Phytophthora infestans. Eur J Plant Pathol 152:561–565. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10658-018-1498-4

Parawira W, Murto M, Zvauya R, Mattiasson B (2004) Anaerobic batch digestion of solid potato waste alone and in combination with sugar beet leaves. Renew Energ 29:1811–1823. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2004.02.005

Qin J, Bian C, Liu J, Zhang J, Jin L (2019) An efficient greenhouse method to screen potato genotypes for drought tolerance. Sci Hortic 253:61–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2019.04.017

Rigby H, Clarke BO, Pritchard DL, Meehan B, Beshah F, Smith SR, Porter NA (2016) A critical review of nitrogen mineralization in biosolids–amended soil, the associated fertilizer value for crop production and potential for emissions to the environment. Sci Total Environ 541:1310–1338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.08.089

Rovira P, Vallejo VR (2007) Labile, recalcitrant, and inert organic matter in Mediterranean forest soils. Soil Biol Biochem 39:202–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2006.07.021

Scott GJ, Rosegrant MW, Ringler C (2000) Global projections for root and tuber crops to the year 2020. Food Policy 25:561–597. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-9192(99)00087-1

Scott GJ, Petsakos A, Juarez H (2019) Climate change, food security, and future scenarios for potato production in India to 2030. Food Secur 11(1):43–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-019-00897-z

Stehel V, Maroušková A, Kolář L (2018) Techno-economic analysis of fermentation residues management places a question mark against current practices. Energ Source Part A 40:721–726. https://doi.org/10.1080/15567036.2018.1457738

Škapa S, Vochozka M (2019) Waste energy recovery improves price competitiveness of artificial forage from rapeseed straw. Clean Technol Environ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10098-019-01697-x

Thu CTT, Cuong PH, Van Chao N, Trach NX, Sommer SG (2012) Manure management practices on biogas and non–biogas pig farms in developing countries–using livestock farms in Vietnam as an example. J Clean Prod 27:64–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.01.006

Tillault AS, Yevtushenko DP (2019) Simple sequence repeat analysis of new potato varieties developed in Alberta. Can Plant Direct 3(6):e00140. https://doi.org/10.1002/pld3.140

Tuśnio A, Pastuszewska B, Święch E, Taciak M (2011) Response of young pigs to feeding potato protein and potato fibre–nutritional, physiological and biochemical parameters. J Anim Feed Sci 20(3):361–378. https://doi.org/10.22358/jafs/66192/2011

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Water–Office of Science and Technology, Engineering and Analysis Division (2001) Method 1684. Total, fixed, and volatile solids in water, solids, and biosolids

Vochozka M, Maroušková A, Straková J, Váchal J (2016a) Techno-economic analysis of waste paper energy utilization. Energy Source Part A 38(23):3459–3463. https://doi.org/10.1080/15567036.2016.1159262

Vochozka M, Maroušková A, Váchal J, Straková J (2016b) Biochar pricing hampers biochar farming. Clean Technol Environ 18(4):1225–1231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10098-016-1113-3

Wang S, Li C, Copeland L, Niu Q, Wang S (2015) Starch retrogradation: A comprehensive review. Compr Rev Food Sci F 14:568–585. https://doi.org/10.1111/1541-4337.12143

Willersinn C, Mouron P, Mack G, Siegrist M (2017) Food loss reduction from an environmental, socio–economic and consumer perspective–The case of the Swiss potato market. Waste Manage 59:451–464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2016.10.007

Zarzecka K, Gugała M (2018) The effect of herbicides and biostimulants on sugars content in potato tubers. Plant Soil Environ 64(2):82–87. https://doi.org/10.17221/21/2018-PSE

Zhang C, Lim ST, Chung HJ (2019) Physical modification of potato starch using mild heating and freezing with minor addition of gums. Food Hydrocolloids 94:294–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodhyd.2019.03.027

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Maroušek, J., Rowland, Z., Valášková, K. et al. Techno-economic assessment of potato waste management in developing economies. Clean Techn Environ Policy 22, 937–944 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10098-020-01835-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10098-020-01835-w