Abstract

The purpose of this investigation was to evaluate the impact of liver stiffness (LS) on the response to direct-acting antiviral (DAA)-based therapy against hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in cirrhotic patients. Those patients included in two Spanish prospective cohorts of patients receiving therapy based on at least one DAA, who showed a baseline LS ≥ 12.5 kPa and who had reached the scheduled time point for sustained virological response evaluation 12 weeks after completing therapy (SVR12) were analysed. Pegylated interferon/ribavirin-based therapy plus an HCV NS3/4A protease inhibitor (PR-PI group) was administered to 198 subjects, while 146 received interferon-free regimens (IFN-free group). The numbers of patients with SVR12 according to an LS < 21 kPa versus ≥21 kPa were 59/99 (59.6%) versus 46/99 (46.5%) in the PR-PI group (p = 0.064) and 41/43 (95.3%) versus 90/103 (87.4%) in the IFN-free group (p = 0.232). Corresponding figures for the relapse rates in those who presented end-of-treatment response (ETR) were 3/62 (4.8%) versus 10/56 (17.9%, p = 0.024) and 1/42 (2.4%) versus 8/98 (8.2%, p = 0.278), respectively. In a multivariate analysis adjusted for age, sex and use of interferon, a baseline LS ≥ 21 kPa was identified as an independent predictor of relapse [adjusted odds ratio, AOR (95% confidence interval, CI): 4.228 (1.344–13.306); p = 0.014] in those patients with ETR. LS above 21 kPa is associated with higher rates of relapse to DAA-based therapy in HCV-infected patients with cirrhosis in clinical practice. LS could help us to tailor the duration and composition of DAA-based combinations in cirrhotic subjects, in order to minimise the likelihood of relapse.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The presence of cirrhosis is usually associated with a poorer response to therapy against chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. This was demonstrated for dual therapy consisting of pegylated (Peg) interferon (IFN) plus ribavirin (RBV) [1, 2]. Also, lower rates of sustained virologic response (SVR) have been reported in patients with cirrhosis who receive treatment regimens based on an NS3/4A protease inhibitor (PI) in combination with Peg-IFN plus RBV [3–10]. With the availability of interferon-free direct-acting antiviral (DAA) regimens, very high overall SVR rates can be achieved and the difference in response rates between cirrhotic and non-cirrhotic patients has become much lower [11–13]. However, there is evidence that the presence of cirrhosis still has an impact on the likelihood of SVR [14], especially in patients harbouring HCV genotypes 2 and 3 who receive the currently recommended combinations [15, 16]. Consequently, specific clinical trials and sub-studies within clinical trials in cirrhotic patients are still being conducted. Importantly, lower response rates to DAA are mainly driven by elevated relapse. Therefore, longer courses of treatment and RBV-including combinations are often recommended in patients with cirrhosis, in order to reduce the likelihood of relapse [17, 18].

In the recent decade, liver stiffness (LS) determination by means of transient elastometry has become a widely accepted method for the evaluation of liver fibrosis in HCV-infected patients with or without human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) coinfection [19–21]. Thus, clinical trials and studies include patients with an LS above a specific threshold, commonly >12.5–14.6 kPa, to define a sub-population bearing cirrhosis. Importantly, LS also has a predictive capacity for the presence of portal hypertension and oesophageal varices [22–24] and different levels of LS are strongly associated with the clinical outcome of cirrhosis [25]. Additionally, transient elastometry represents a non-invasive tool to identify patients with persistent clinically significant portal hypertension after achieving SVR. However, the median levels of LS differ considerably between clinical trials and studies aimed at evaluating the efficacy and safety of therapy against HCV infection in patients with cirrhosis. In addition, response according to the level of LS have scarcely been analysed in cirrhotic subjects receiving DAA-based combinations, in spite of the fact that the degree of LS was independently associated with the likelihood to achieve SVR to dual therapy with Peg-IFN/RBV within this subset [2].

The aim of this study was to evaluate the impact of LS on the response to DAA-based therapy against chronic HCV infection in patients with cirrhosis in real-life practice.

Patients and methods

Study design and population

This is an analysis of the prospective HEPAVIR-DAA (clinicaltrials.gov ID: NCT02057003) and GEHEP-MONO (clinicaltrials.gov ID: NCT02333292) cohorts. In these cohorts, all patients seen at the Infectious Diseases Units of 32 hospitals throughout Spain who initiate therapy against chronic hepatitis C including one or more DAA are included since October 2011. HIV/HCV-coinfected patients are included in the HEPAVIR-DAA cohort, while HCV-monoinfected subjects are included in the GEHEP-MONO cohort. Patients are seen at least at treatment weeks 4, 12 and, if applicable, 24 and 48, as well as 12 weeks after the scheduled end of treatment. At baseline and each follow-up visit, plasma HCV-RNA is quantified and haematological and biochemical parameters are determined. Before starting therapy, a transient elastometry examination is conducted in all patients to determine LS. For the present analysis, all those patients who fulfilled the following criteria were selected: (i) baseline LS ≥ 12.5 kPa, (ii) having received Peg-IFN-based therapy in combination with an HCV NS3/4A PI or a Peg-IFN-free combination of at least two DAA with or without RBV. The treatment outcome 12 weeks after the scheduled end of therapy was considered for analysis.

Treatment groups, patient management and definition of response

Patients were classified into two study groups: (1) those who received a three-drug combination including the NS3/4A PI boceprevir (BOC), telaprevir (TVR) or simeprevir (SMV) in combination with Peg-IFN alpha-2a or Peg-IFN alpha-2b plus weight-adjusted oral RBV (PR-PI group) and (2) those subjects who were given paritaprevir (PTV), ritonavir-boosted ombitasvir (OBT/r) with or without dasabuvir (DBV) and/or RBV, or a DAA combination including sofosbuvir (SOF) plus either SMV, daclatasvir (DCV) or ledipasvir (LED) with or without RBV (IFN-free group). Treatment duration and futility rules, if applicable, were in accordance with the package insert and clinical guidelines [17, 18]. End-of-treatment response (ETR) was considered when HCV RNA was undetectable at the scheduled end of therapy in those subjects who completed treatment. Relapse was defined as detectable HCV RNA at week 12 post-treatment in the population who had achieved ETR. Undetectable HCV RNA 12 weeks after the scheduled end of therapy was defined as SVR12. The patient was considered a non-responder to the respective NS3/4A PI when the stopping rules were met [18]. Detectable HCV RNA on therapy following undetectability was considered as viral breakthrough. Management of adverse events was carried out according to the criteria of caring physicians.

LS determinations and classification of cirrhosis

LS was measured by transient elastometry (FibroScan®, Echosens, Paris, France). The determination was considered valid if at least ten successful measurements could be conducted, with an interquartile range lower than 30% of the median value and a success rate of more than 60%. For the purposes of this study, cirrhosis was diagnosed in patients who presented an LS ≥ 12.5 kPa.

Statistical analysis

The outcome variable was relapse in the population who had presented with ETR. Furthermore, the rates of SVR12, treatment discontinuations due to adverse events, as well as non-response or viral breakthrough (NR/VB), were assessed as secondary end-points. Youden’s index J was calculated by means of receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves in order to determine the most adequate cut-off value for the primary outcome variable [26]. Continuous variables were expressed as median (Q1–Q3) and categorical variables as number (percentage). The impact of LS on relapse, as well as comparisons of other categorical variables, were analysed using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test, when applicable. Finally, a multivariate logistic regression analysis was applied, adjusting for age, sex, as well as for those factors that were associated with a p < 0.2 in a univariate analysis. Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS statistical software package release 23.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics and regimens

In two out of 346 eligible subjects, both had compensated cirrhosis and were successfully treated with IFN-based therapy, but the LS measurement did not meet the criteria of validity. Thus, a total of 344 patients were included in this study: 287 (83.4%) were male, the median age was 50.3 (46.7–54.2) years and 207 (60.2%) were coinfected with HIV. The median (Q1–Q3) baseline LS in the overall population was 24.4 (17.3–34.8) kPa. One hundred and ninety-eight (57.6%) subjects received an NS3/4A PI in combination with IFN and RBV, mainly TVR (70.7%), followed by BOC (26.8%) and SMV (2.5%), representing the PR-PI group. Among the 146 patients who were entered in the IFN-free group, the numbers of subjects receiving different DAA combinations were: 90 (61.6%) for SOF/SMV, 43 (29.5%) for SOF/DCV, 12 (8.2%) for SOF/LED and 1 (0.7%) for PTV/OBT/r/DBV. In this group, RBV was applied in 15 (34.9%) patients with an LS < 21 kPa and in 42 (40.8%) of those with an LS ≥ 21 kPa. The programmed treatment duration was 12 weeks in all of the subjects with a, LS < 21 kPa, while a 24-week therapy was scheduled in 18 (17.5%) patients with an LS ≥ 21 kPa. The baseline characteristics of the two populations are shown in Table 1.

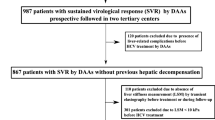

Response to therapy

ETR was achieved by 258 (75%) subjects: 118 (59.6%) subjects of the PR-PI group and 140 (95.9%) individuals of the IFN-free group. The numbers of patients who relapsed after having presented ETR were 13 (11%) subjects in the PR-PI group and 9 (6.4%) in the IFN-free group. A total of 236 (69%) subjects presented SVR12. The numbers of SVR12 according to treatment group, as well as other treatment outcomes, are shown in Fig. 1.

Impact of LS on treatment response

An analysis of the ROC curve for the capacity of LS to predict relapse in the sub-population of those who achieved ETR disregarding the treatment regimen yielded a maximum J for an LS cut-off value of 20.95 kPa. Due to these findings, a rounded cut-off value of 21 kPa was selected for further analysis. Of the 104 patients who presented a baseline LS < 21 kPa, 4 (3.8%) presented relapse, while 18/154 (11.7%) of those with an LS ≥ 21 kPa relapsed (p = 0.027). Table 2 sums up the main characteristics of these individuals. Relapse rates, as well as SVR12 rates, according to baseline LS within the different study groups are shown in Fig. 2.

Rates of relapse among those patients who had reached end-of-treatment response (n = 258) (a) and rates of sustained virologic response 12 weeks after scheduled end of therapy (SVR12) (b), according to baseline liver stiffness and study group. PR Pegylated interferon plus ribavirin; PI protease inhibitor; IFN interferon

SVR12 analysed in an intention-to-treat basis was observed in 100/142 (70.4%) patients who presented a baseline LS < 21 kPa and 136/202 (67.3%) of those with an LS ≥ 21 kPa (p = 0.542). Rates of SVR12 according to the baseline LS for the two study groups are shown in Fig. 2b. Twenty-three out of 99 (23.2%) subjects with an LS < 21 kPa versus 24/99 (24.2%) patients with an LS ≥ 21 kPa presented NR/VB in the PR-PI group (p = 0.867), while NR/VB was not shown by any patient of the IFN-free group. Discontinuations due to adverse events in the PR-PI group were observed in 10/99 (10.1%) subjects with an LS < 21 kPa versus 14/99 (14.1%) individuals with an LS ≥ 21 kPa (p = 0.384). The corresponding figures for the IFN-free group were 0/43 (0%) versus 1/103 (1%) patients (p = 1).

In a multivariate analysis, baseline LS ≥ 21 kPa was the only factor independently associated with relapse in patients who attained ETR [adjusted odds ratio, AOR (95% confidence interval, CI): 4.228 (1.344–13.306); p = 0.014]. The detailed univariate and multivariate analyses are shown in Table 3.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates that cirrhotic patients with LS above 21 kPa present higher relapse rates after receiving DAA-based therapy in the clinical practice. This effect is predominantly observed when an HCV NS3/4A PI in combination with Peg-IFN and RBV is applied, but the relapse rate is also numerically higher in subjects with LS over this threshold receiving IFN-free combinations. As a consequence of this, the SVR rate tended to be lower in subjects with LS ≥ 21 kPa, which was driven by the relapse rate rather than by a different frequency of discontinuations due to side effects or of other therapy outcomes.

Relapse is the most frequent way of virologic failure to DAA-based, IFN-free therapy [3, 12, 13, 27, 28], even as far as most recently developed drugs are concerned [29]. Furthermore, patients who relapse to therapy often present viral strains that are resistant to the drugs applied and to other drugs from the same family, therefore limiting future treatment options [30]. For these reasons, it is critical to identify patients who are more prone to relapse after therapy. Furthermore, extending treatment duration [14, 31, 32] or the addition of RBV [32–35] in patients with a higher probability of relapse could minimise the possibility for this event. Thus, patients with an LS > 21 kPa may benefit from prolonged therapy, while those who have a lower baseline LS might be candidates for shorter therapy or RBV-free combinations, a hypothesis that should be tested in properly designed clinical trials. In the meanwhile, given the higher likelihood of relapse, in our opinion, the treatment approach for cirrhotic patients with an LS above 21 kPa should be based on the use of strategies implying the maximum duration for each combination and/or the addition of RBV, especially in those patients who show other unfavourable parameters. This could have a major impact on the optimisation of patient management.

Most clinical trials conducted in cirrhotic patients did not analyse the impact of baseline LS on response and there are only little data which suggest LS having a potential impact on the response. Lawitz and colleagues report a relapse rate to SOF/SMV of 0% versus 14% for patients with an LS of 12.5–20 kPa and >20 kPa, respectively [27]. Furthermore, in a pooled analysis of phase II and III trials on SOF/LED with or without RBV conducted in cirrhotic patients, an LS equal to or below 20 kPa tended to impact on SVR12, although statistical significance was not reached [36]. In the present study, LS was identified as an independent predictor of relapse in those patients who reached ETR. This finding demonstrates that response rates should be adjusted for LS in order to accurately interpret and compare the results in cirrhotic patients. Importantly, the data presented herein show a clear numerical disadvantage in terms of relapse after IFN-free therapy when presenting a baseline LS above 21 kPa. Relapse rates were three times higher in those patients with an LS equal to or above 21 kPa, and it is to note that the only patient who relapsed in the sub-population with an LS of <21 kPa presented an LS value of 19.6 kPa.

Interestingly, the determination of the most adequate cut-off value yielded a value which has been previously described to have clinical significance [22, 25, 37]. In this context, this cut-off can be considered an adequate marker of significant portal hypertension [37]. Interestingly, portal hypertension has been identified as a strong predictor of response to Peg-IFN and RBV [38], while this effect was not seen in a different study on IFN-free regimens [39]. However, in the latter study, response-guided therapy was used and prolonged treatment duration may have overcome the predictive value of clinically significant portal hypertension [39], while in the present study, treatment duration was defined according to baseline characteristics. The presence of significant portal hypertension has led some authors to propose a classification of cirrhosis, because those patients with this finding have a more severe liver damage and a poorer clinical outcome [40]. Also, 21 kPa has a 100% negative predictive value for the presence of varices at risk of bleeding [22] and patients maintaining LS under this threshold do not suffer from portal hypertensive gastrointestinal bleeding [41]. The results of this study show that this level of LS is associated, not only to a poorer clinical condition, but to a higher rate of relapse to DAA-based therapy.

Cirrhotic patients with more advanced liver disease such as those in Child–Pugh–Turcotte (CPT) class C respond worse to therapy [42–45]. In the preliminary results from a clinical trial of post-transplant patients treated with SOF/LED/RBV, the SVR12 rates suggest a decline in SVR rates according to increasing CPT stage [42]. Similar observations have been made among patients treated with SOF/DCV/RBV within the ALLY-1 trial, where CPT class C patients showed considerably poorer response rates as compared to CPT A/B [43]. In the present study, the degree of LS did not impact on the rates of discontinuations due to adverse events.

This study has limitations. Due to the generally high response rates to IFN-free DAA-based therapy, the lack of statistical power may have impeded the detection of a statistically significant impact of LS on relapse rates to IFN-free regimens in the univariate analysis. However, there was a clear numerical difference, which is clinically relevant, given that no relapse should be the objective of an optimal DAA therapy. Likewise, the regimens applied in the IFN-free group were considerably heterogeneous. Also, scheduled treatment duration was longer in approximately one-fifth of those subjects with an LS ≥ 21 kPa, However, as stated by the reviewer, this individual treatment optimisation would rather have attenuated the association between high LS and relapse rates. Studies with a larger sample size and stratified for the different drugs are needed.

In conclusion, the degree of LS impacts on the relapse rate to DAA-based therapy in the clinical practice. This should be considered when designing clinical trials in cirrhotic patients, as patients should be stratified according to whether they have LS below or above 21 kPa. In addition, patients with an LS < 21 kPa could be candidates to shorter regimens and/or RBV-free combinations. Clinical trials exploring these alternatives are warranted.

References

Bruno S, Shiffman ML, Roberts SK et al (2010) Efficacy and safety of peginterferon alfa-2a (40KD) plus ribavirin in hepatitis C patients with advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis. Hepatology 51:388–397

Mira JA, García-Rey S, Rivero A et al (2012) Response to pegylated interferon plus ribavirin among HIV/hepatitis C virus-coinfected patients with compensated liver cirrhosis. Clin Infect Dis 55:1719–1726

Poordad F, McCone J Jr, Bacon BR et al (2011) Boceprevir for untreated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med 364:1195–1206

Bacon BR, Gordon SC, Lawitz E et al (2011) Boceprevir for previously treated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med; 364:1207–1217

Jacobson IM, McHutchison JG, Dusheiko G (2011) Telaprevir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med 364:2405–2416

Zeuzem S, Andreone P, Pol S et al (2011) Telaprevir for retreatment of HCV infection. N Engl J Med 364:2417–2428

Jacobson IM, Dore GJ, Foster GR et al (2014) Simeprevir with pegylated interferon alfa 2a plus ribavirin in treatment-naive patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection (QUEST-1): a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 384:403–413

Manns M, Marcellin P, Poordad F et al (2014) Simeprevir with pegylated interferon alfa 2a or 2b plus ribavirin in treatment-naive patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection (QUEST-2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 384:414–426

Zeuzem S, Berg T, Gane E et al (2014) Simeprevir increases rate of sustained virologic response among treatment-experienced patients with HCV genotype-1 infection: a phase IIb trial. Gastroenterology 146:430–441.e6

Forns X, Lawitz E, Zeuzem S et al (2014) Simeprevir with peginterferon and ribavirin leads to high rates of SVR in patients with HCV genotype 1 who relapsed after previous therapy: a phase 3 trial. Gastroenterology 146:1669–1679.e3

Afdhal N, Zeuzem S, Kwo P et al (2014) Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for untreated HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med 370:1889–1898

Naggie S, Cooper C, Saag M et al (2015) Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for HCV in patients coinfected with HIV-1. N Engl J Med 373:705–713

Wyles DL, Ruane PJ, Sulkowski MS et al (2015) Daclatasvir plus sofosbuvir for HCV in patients coinfected with HIV-1. N Engl J Med 373:714–725

Afdhal N, Reddy KR, Nelson DR et al (2014) Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for previously treated HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med 370:1483–1493

Nelson DR, Cooper JN, Lalezari JP et al (2015) All-oral 12-week treatment with daclatasvir plus sofosbuvir in patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 3 infection: ALLY-3 phase III study. Hepatology 61:1127–1135

Foster GR, Pianko S, Cooper C et al (2015) Sofosbuvir + peginterferon/ribavirin for 12 weeks vs sofosbuvir + ribavirin for 16 or 24 weeks in genotype 3 HCV infected patients and treatment-experienced cirrhotic patients with genotype 2 HCV: the BOSON study. In: Proceedings of the 50th Annual Meeting of the European Association for the Study of the Liver, Vienna, Austria. 22–26 April 2015. Abstract L05

Documento de consenso del Grupo Español para el Estudio de la Hepatitis (GEHEP) sobre el tratamiento de la hepatitis C. Available online at: http://seimc.org/grupodeestudio.php?Grupo=GEHEP&mn_Grupoid=14&mn_MP=512&mn_MS=513. Accessed 10 October 2016

European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL). EASL Recommendations on Treatment of Hepatitis C 2015. Available online at: http://www.easl.eu/medias/cpg/HEPC-2015/Full-report.pdf. Accessed 10 October 2016

Sandrin L, Fourquet B, Hasquenoph JM et al (2003) Transient elastography: a new noninvasive method for assessment of hepatic fibrosis. Ultrasound Med Biol 29:1705–1713

Castéra L, Vergniol J, Foucher J et al (2005) Prospective comparison of transient elastography, Fibrotest, APRI, and liver biopsy for the assessment of fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology 128:343–350

Vergara S, Macías J, Rivero A et al (2007) The use of transient elastometry for assessing liver fibrosis in patients with HIV and hepatitis C virus coinfection. Clin Infect Dis 45:969–974

Pineda JA, Recio E, Camacho A et al (2009) Liver stiffness as a predictor of esophageal varices requiring therapy in HIV/hepatitis C virus-coinfected patients with cirrhosis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 51:445–459

Vizzutti F, Arena U, Romanelli RG et al (2007) Liver stiffness measurement predicts severe portal hypertension in patients with HCV-related cirrhosis. Hepatology 45:1290–1297

Mandorfer M, Kozbial K, Schwabl P et al (2016) Sustained virologic response to interferon-free therapies ameliorates HCV-induced portal hypertension. J Hepatol 65:692–699

Merchante N, Rivero-Juárez A, Téllez F et al (2012) Liver stiffness predicts clinical outcome in human immunodeficiency virus/hepatitis C virus-coinfected patients with compensated liver cirrhosis. Hepatology 56:228–238

Youden WJ (1950) Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer 3:32–35

Lawitz E, Matusow G, DeJesus E et al (2016) Simeprevir plus sofosbuvir in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection and cirrhosis: a phase 3 study (OPTIMIST-2). Hepatology 64:360–369

Mauss S, Schewe K, Rockstroh JK et al (2015) Sofosbuvir-based treatments for patients with hepatitis C virus (HCV) mono-infection and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–HCV co-infection with genotype 1 and 4 in clinical practice—results from the GErman hepatitis C COhort (GECCO). In: Proceedings of the 66th Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 November 2015. Abstract 1156

Sulkowski M, Hezode C, Gerstoft J et al (2015) Efficacy and safety of 8 weeks versus 12 weeks of treatment with grazoprevir (MK-5172) and elbasvir (MK-8742) with or without ribavirin in patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 1 mono-infection and HIV/hepatitis C virus co-infection (C-WORTHY): a randomised, open-label phase 2 trial. Lancet 385:1087–1097

Poveda E, Wyles DL, Mena A et al (2014) Update on hepatitis C virus resistance to direct-acting antiviral agents. Antiviral Res 108:181–191

Poordad F, Hezode C, Trinh R et al (2014) ABT-450/r-ombitasvir and dasabuvir with ribavirin for hepatitis C with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med 370:1973–1982

Reddy KR, Bourlière M, Sulkowski M et al (2015) Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir in patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C virus infection and compensated cirrhosis: an integrated safety and efficacy analysis. Hepatology 62:79–86

Ferenci P, Bernstein D, Lalezari J et al (2014) ABT-450/r-ombitasvir and dasabuvir with or without ribavirin for HCV. N Engl J Med 370:1983–1992

Nelson DR, Cooper JN, Lalezari JP et al (2015) All-oral 12-week treatment with daclatasvir plus sofosbuvir in patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 3 infection: ALLY-3 phase III study. Hepatology 61:1127–1135

Leroy V, Angus P, Bronowicki JP et al (2015) All-oral treatment with daclatasvir (DCV) plus sofosbuvir (SOF) plus ribavirin (RBV) for 12 or 16 weeks in HCV genotype (GT) 3-infected patients with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis: the ALLY-3+ phase 3 study. In: Proceedings of the 66th Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 November 2015. Abstract LB-3

Reddy KR, Bourlière M, Sulkowski M et al (2015) Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir in patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C virus infection and compensated cirrhosis: an integrated safety and efficacy analysis. Hepatology 62:79–86

Bureau C, Metivier S, Peron JM et al (2008) Transient elastography accurately predicts presence of significant portal hypertension in patients with chronic liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 27:1261–1268

Reiberger T, Rutter K, Ferlitsch A et al (2011) Portal pressure predicts outcome and safety of antiviral therapy in cirrhotic patients with hepatitis C virus infection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 9:602–608.e1

Mandorfer M, Kozbial K, Freissmuth C et al (2015) Interferon-free regimens for chronic hepatitis C overcome the effects of portal hypertension on virological responses. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 42:707–718

Garcia-Tsao G, Friedman S, Iredale J, Pinzani M (2010) Now there are many (stages) where before there was one: In search of a pathophysiological classification of cirrhosis. Hepatology 51:1445–1449

Merchante N, Rivero-Juárez A, Téllez F et al (2016) Liver stiffness predicts variceal bleeding in HIV/HCV-coinfected patients with compensated cirrhosis. AIDS (in press)

Charlton M, Everson GT, Flamm SL et al (2015) Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir plus ribavirin for treatment of HCV infection in patients with advanced liver disease. Gastroenterology 149:649–659

Poordad F, Schiff ER, Vierling JM et al (2016) Daclatasvir with sofosbuvir and ribavirin for hepatitis C virus infection with advanced cirrhosis or post-liver transplantation recurrence. Hepatology 63:1493–1505

Manns M, Samuel D, Gane EJ et al (2016) Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir plus ribavirin in patients with genotype 1 or 4 hepatitis C virus infection and advanced liver disease: a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Infect Dis 16:685–697

Curry MP, O’Leary JG, Bzowej N et al (2015) Sofosbuvir and velpatasvir for HCV in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. N Engl J Med 373:2618–2628

Acknowledgements

Other members of the GEHEP-SEIMC/HEPAVIR Group are: Helena Albendín, María Remedios Alemán, María del Mar Alonso, Victor Asensi, María José Blanco, Javier Borrallo, Rebeca Cabo, Ángela Camacho, Mario Frías Casas, Ángeles Castro, Antonio Collado, Sandra Cuellar, Francisca Cuenca, Marcial Delgado, Carlos Dueñas, Elisa Fernández, Carlos Galera, María Carmen Gálvez, Dácil García, Paloma Geijo Martínez, Ana Gómez, Juan Luis Gómez, Félix Gutiérrez, José Hernández, Jehovana Hernández, Jara Llenas-García, María Mancebo, José María Martín, Lorena Martínez, Rosa Martínez-Álvarez, Onofre Martínez Madrid, María del Mar Masiá, Nicolás Merchante, Patricia Monje, Marta Montero-Alonso, Rocío Nuñez, Guillermo Ojeda, Sergio Padilla, Catarina Robledano, Ricardo Pelazas, Elisabet Pérez, Inés Pérez-Camacho, Montserrat Pérez-Pérez, Berta Pernas, José Joaquín Portu, Miguel Raffo, Luis M. Real, Gabriel Reina, Sergio Reus, María José Ríos, Antonio Rivero, Joaquín Portilla, Purificación Rubio, Pablo Saíz de la Hoya, Ignacio de los Santos-Gil, Jesús Santos, Miriam Serrano, Marta Suárez-Santamaría, Francisco Téllez, Carla Toyas, Francisco Jesús Vera-Méndez, Antonio Vergara, David Vinuesa García.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This work has been partially funded by the RD12/0017/0012 project as part of the Plan Nacional R+D+I and cofinanced by ISCIII-Subdirección General de Evaluación, the Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER) and the Consejería de Salud of the Junta de Andalucía (grant numbers AC-0095-2013 and PI-0492-2012). K.N. is the recipient of a Miguel Servet research grant from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (grant number CP13/00187). A.R.-J. is the recipient of a post-doctoral perfection grant from the Consejería de Salud of the Junta de Andalucía (grant number RH-0024/2013). J.M. is the recipient of a grant from the Servicio Andaluz de Salud of the Junta de Andalucía (grant number B-0037). J.A.P. is the recipient of an intensification grant from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (grant number Programa-I3SNS).

Conflict of interest

K.N. has received lecture fees from Janssen-Cilag, Roche, Bristol-Meyers Squibb and Merck Sharp & Dohme, research support from Janssen-Cilag, Bristol-Meyers Squibb, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Gilead Sciences and Abbott Pharmaceuticals and travel expenses from Janssen-Cilag, ViiV Healthcare, Roche, Bristol-Meyers Squibb and Merck Sharp & Dohme. A.R.-J. has received lecture fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Pfizer, ViiV Healthcare and Roche. J.M. has been an investigator in clinical trials supported by Roche, Bristol-Myers Squibb and Abbott Pharmaceuticals and has received lecture fees from Roche, Gilead Sciences, Boehringer Ingelheim and Bristol-Myers Squibb and consulting fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck Sharp & Dohme and Schering-Plough. R.G. reports having received lecture fees from Roche, Gilead Sciences, Janssen Cilag and Merck Sharp & Dohme. He has received consultancy fees from Janssen Cilag and Abbvie. M.M. reports having received consulting fees from Gilead Sciences and Janssen-Cilag and lecture fees from Abbvie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Janssen-Cilag, Merck-Sharp & Dome and ViiV Healthcare. D.M. reports having received consultancy fees from Janssen Cilag, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Abbvie and ViiV Healthcare. J.C. has received consultancy fees from Janssen Cilag, Bristol-Myers Squibb and Gilead Sciences and lecture fees from Janssen Cilag, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, ViiV Healthcare and Merck Sharp & Dohme. M.O. has received lecture fees from Abbvie, ViiV Healthcare, Gilead Sciences, Janssen-Cilag, Bristol-Myers Squibb and Merck Sharp & Dohme. J.A.P. reports having received consulting fees from GlaxoSmithKline, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Abbott Pharmaceuticals, Gilead Sciences, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Schering-Plough, Janssen-Cilag and Boehringer Ingelheim. He has received research support from GlaxoSmithKline, Roche, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Schering-Plough, Abbott Pharmaceuticals and Boehringer Ingelheim and has received lecture fees from GlaxoSmithKline, Roche, Abbott Pharmaceuticals, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Janssen-Cilag, Boehringer Ingelheim and Schering-Plough. All other authors: none to declare.

Ethical approval

The study was designed and performed according to the Helsinki declaration and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Valme University Hospital (Seville, Spain).

Informed consent

All patients gave their written informed consent before being included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Neukam, K., Morano-Amado, L.E., Rivero-Juárez, A. et al. Liver stiffness predicts the response to direct-acting antiviral-based therapy against chronic hepatitis C in cirrhotic patients. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 36, 853–861 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-016-2871-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-016-2871-x