Abstract

We determined the fecal carriage rate of serotype K1 Klebsiella pneumoniae in healthy Koreans and studied their genetic relationship with liver abscess isolates. We compared the carriage according to the country of residence. The stool specimens were collected through health promotion programs in Korea. K. pneumoniae strains were selected and tested for K1 by PCR. Serotype K1 isolates were characterized by multilocus sequence typing and pulsed field gel electrophoresis. A total of 248 K. pneumoniae isolates were obtained from 1,174 Koreans. Serotype K1 was identified in 57 (4.9%), of which 54 (94.7%) were ST 23 and were closely related to the liver abscess isolates. Participants aged >25 years showed a higher fecal carriage rate than those ≤ 25 (P = 0.007). The proportion of serotype K1 out of K. pneumoniae isolates in foreigners of Korean ethnicity who had lived in other countries was lower compared with those who had lived in Korea (5.6% vs 24.1%, P = 0.024). A substantial proportion of Koreans >25 years carries serotype K1 K. pneumoniae ST23 strains, which are closely related to liver abscess isolates. Differences in carriage rates by country of residence suggests that environmental factors might play an important role in the carriage of this strain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Klebsiella pneumoniae has become a major pathogen causing liver abscess in Korea and Taiwan over the past two decades [1, 2]. Even though reports on K. pneumoniae liver abscess have also been increasing in western countries [3, 4], they are much more common in Asian countries. Furthermore, the serotype K1 strain belonging to sequence type (ST) 23 has been found to be responsible for an increasing incidence of this infection in Korea [5]. Serotypes K1 and K2 have shown the highest virulence in mice out of the 77 serotypes [6], and are more resistant to phagocytosis [7]. Despite its high virulence, however, serotype K1 had been rare in the clinical isolates from western countries [8, 9], although a report from Australia showed that six out of 293 K. pneumoniae clinical isolates collected from 2001 to 2002 were serotype K1 [10]. There has been no clear explanation for the geographical difference observed in the epidemiology of K. pneumoniae liver abscess.

Various factors including ethnicity, host susceptibility to infection, difference in carriage rates, and environmental factors might be potentially contributing to such a geographical difference in epidemiology of K. pneumoniae infection. K. pneumoniae can colonize the gastrointestinal tract of humans, and it has been suggested that colonization by the serotype K1 K. pneumoniae strains precedes invasion of the intestinal mucosa and portal venous flow or ascending biliary infection, which is followed by the development of liver abscess [11, 12]. However, whether this virulent strain is present in the intestinal microbiota of healthy adults has not been tested yet.

Therefore, in this study the fecal carriage rate of serotype K1 K. pneumoniae was investigated in healthy Korean adults. The genetic relationship between the fecal isolates identified in this study and the liver abscess isolates that had been previously reported was examined. In addition, we compared the fecal carriage of this strain among foreigners who are ethnic Koreans according to whether they had lived in Korea or other countries in the previous year in order to understand the roles of ethnic factors and environmental factors in the epidemiology of diseases caused by these strains.

Materials and methods

Study population and bacterial isolates

This study was approved by Samsung Medical Center Institutional Review Board, and met the exemption criteria from the informed consent requirements. The stool specimens from Korean adults were prospectively collected through health promotion programs at 10 university-affiliated hospitals, which were located nationwide in South Korea in 2007 (one center in 2005). The remaining stool specimens after parasite examination and occult blood test in health promotion programs were used in this study. A total of 65 to 240 stool specimens were collected over 2 to 7 days from each hospital. The subjects were enrolled without any exclusion criteria. Demographic information including age, gender, province of residence, and blood glucose level was extracted from the electronic database of the health promotion programs of the hospitals.

The stool specimens from the foreigners who are ethnic Koreans were collected through a health promotion program for foreigners at Samsung Medical Center from September 2009 to March 2010. The information including nationality, ethnicity, and country of residence in the previous year was collected through the printed questionnaires. For the subjects who did not return the questionnaires and carried K. pneumoniae in feces, information was further collected by telephone questionnaires.

Stool specimens were inoculated into the culture media within 24 to 72 h from sample collection. In 2009, we used enrichment media before we inoculated into the selection media. K. pneumoniae strains were selected using MCIK (MacConkey-inositol-potassium tellurite) media, as described previously [13] and five colonies were tested from an individual subject. K. pneumoniae was identified using the API-20E test kits (bioMerieux, Hazelwood, MO, USA).

Microbiological and genotypic characterization

The serotype K1 was determined by PCR using a primer pair specific for magA, which is a gene specific for the K1 antigen. The primers were chosen as previously described: forward, 5′-GGTGCTCTTTACATCATTGC-3′, and reverse, 5′-GCAATGGCCATTTGCGTTAG-3′ [14].

Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) was performed on the isolates of serotype K1 K. pneumoniae by determining the nucleotide sequences of seven housekeeping genes (gapA, infB, mdh, pgi, phoE, rpoB, and tonB) as described previously [15]. Sequence types were assigned using the K. pneumoniae MLST database (http://www.pasteur.fr/mlst/).

For pulsed field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), agarose-embedded bacterial genomic DNA was digested with 20 U of XbaI. The restriction fragments were separated by electrophoresis in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer. Electrophoresis was performed using a CHEF Mapper XA (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). The PFGE patterns were analyzed using molecular analysis software (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA). Eight isolates of serotype K1 K. pneumoniae from a previous study on liver abscess [5] and two ATCC reference strains of serotype K1 (ATCC8044 and ATCC35593) were also typed for comparison of the PFGE patterns.

Statistical analyses

Continuous variables with non-normal distribution were compared using rank sum test. Categorical variables were compared using the Chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test. A two-tailed P value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Stata software (version 11.1, StataCorp, College Station, TS, USA) was used for statistical analysis.

Results

Fecal carriage of serotype K1 K. pneumoniae among Koreans

A total of 1,174 stool specimens were collected from 10 hospitals and screened for the presence of K. pneumoniae. K. pneumoniae was found in 248 (21.1%) and serotype K1 K. pneumoniae was identified in 57 (4.9%), which was 23.0% of K. pneumoniae isolates. There was no difference in age, gender, province of residence, and serum glucose level between the group carrying serotype K1 K. pneumoniae and the group carrying no K. pneumoniae (Table 1). Median age of the subjects carrying serotype K1 K. pneumoniae was 48 years (range 26–85), and 52.6% were male. The fecal carriage rates of serotype K1 K. pneumoniae varied from 1.0% to 8.0% according to the province of residence, although there was no significant difference. Serotype K1 was not found in 27 K. pneumoniae isolates from the feces of 104 Koreans in the age range of 16 to 25 years (0/104); however, 5.6% (57/1,013) of the subjects older than 25 years carried serotype K1 K. pneumoniae (P = 0.007; Fig. 1).

Genotypic characterization of serotype K1 K. pneumoniae fecal isolates from Koreans

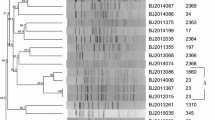

The MLST revealed that 54 (94.7%) of the isolates with serotype K1 belonged to ST23. Two isolates were ST260, double-locus variants (DLV) of ST23. The other isolate, ST424, was totally unrelated. The PFGE patterns of the serotype K1 K. pneumoniae isolates from the feces of healthy Korean adults, 8 isolates from liver abscess, and 2 ATCC strains, which are ST82, were analyzed (Fig. 2). Most isolates of ST23 were clustered into a single group with >69% similarity regardless of whether they were fecal isolates from healthy subjects or liver abscess isolates. A large clonal group and small groups were clustered with >80% similarity.

Comparison of fecal carriage of serotype K1 K. pneumoniae in foreigners who are ethnic Koreans by country of residence

A total of 130 (48.3%) isolates of K. pneumoniae were isolated from 269 foreigners who are ethnic Koreans. For 94 isolates with the information of the place of residence in the previous year, the proportions of serotype K1 K. pneumoniae were compared according to whether they had lived in Korea or not in the previous year (Table 2). The countries in which they had lived in the previous year include Korea (61.7%), USA (26.6%), Canada (8.5%), Australia (1.1%), England (1.1%), and Germany (1.1%). There was no difference in age and gender between the groups. Serotype K1 accounted for only 5.6% (2 out of 36) of K. pneumoniae fecal isolates from the subjects who had been resident in countries other than Korea, whereas this comprised 24.1% (14 out of 58) in the subjects who had been resident in Korea (P = 0.024). Fifteen out of 16 isolates of serotype K1 K. pneumoniae were ST23, and the other one was ST249. Both of the isolates of serotype K1 from subjects who had been resident in the other countries were ST23. The countries of residence were the USA and Canada respectively.

Discussion

The results of this study showed that a substantial proportion of healthy Korean adults carried serotype K1 K. pneumoniae ST23, which is a major etiological organism of liver abscess in Korea, as intestinal flora. Fecal carriage rate of serotype K1 K. pneumoniae in Korean adults older than 25 was 5.3%; most of them were ST23 and were closely related genotypically. Furthermore, they were closely related to the liver abscess isolates previously reported. The finding that younger adults below the age of 25 had a lower rate of fecal carriage of serotype K1 K. pneumoniae suggests the possibility that these strains are acquired after the age of 25 in Korea through unknown external sources. Interestingly, such age distribution seen in intestinal colonization by serotype K1 K. pneumoniae in our study is consistent with that in K. pneumoniae liver abscess. The mean age of the patients with K. pneumoniae liver abscess in a previous nationwide prospective study in Korea was 60 years (SD 13), and only one of the 262 patients was younger than 25 [1].

A much lower proportion of the foreigners of Korean ethnicity who had lived in the countries other than Korea in the previous year carried serotype K1 K. pneumoniae strains, whereas foreigners of Korean ethnicity who had lived in Korea carried serotype K1 K. pneumoniae in a proportion comparable to that of native Koreans. These findings suggest a potential role of environmental factors in the intestinal colonization of these strains. Possible environmental sources for acquisition of these strains might include diets such as meats, uncooked plants, and fermented foods. In fact, it has been reported that K. pneumoniae is ubiquitous in nature and the isolates of environmental origin are identical to clinical isolates with respect to phenotypic properties and pathogenic potentials to humans [16, 17].

In addition to the probable role of environmental factors, virulence factors of serotype K1 K. pneumoniae strains might contribute to favorable colonization of these strains in human intestinal tracts. Capsular polysaccharides have been reported to play an important role in gut colonization by K. pneumoniae [18] as well as in the pathogenesis of invasive infections caused by this organism. Furthermore, serotypes K1 and K2 have been reported to be highly resistant to phagocytosis [7]. These factors might contribute the serotype K1 K. pneumoniae ST23 strain to be adapted to colonize the human intestinal tract. Other factors including socioeconomic status might affect the difference in colonization of these strains.

Our study has some limitations. First, in comparative analysis for the foreigners who are ethnic Koreans, we presented the proportion of serotype K1 among K. pneumoniae fecal isolates rather than the true fecal carriage rate of this strain. Only those persons who were determined to carry K. pneumoniae in their feces were further contacted by telephone to obtain the answers to questionnaires, so the fecal carriage rate of K. pneumoniae could be falsely high in those about whom we have information concerning their place of residence in the previous year. Second, the time period of enrollment was different between the two populations compared, and it could make a bias in comparison. Third, to strengthen our suggestion that environmental factors are important for the intestinal colonization of serotype K1 K. pneumoniae rather than ethnic factors, a study on the foreigners of white ethnicity who had lived for a long time in Korea would also be of value; however, we could not include those in our study. Fourth, information on underlying diseases or conditions, such as diabetes mellitus or antibiotic exposure, was not collected. Those factors could affect the results of our study.

This is the first report to document fecal carriage of the serotype K1 K. pneumoniae ST23 in healthy adults living in the region with a high prevalence rate of K. pneumoniae liver abscess, and to demonstrate that serotype K1 K. pneumoniae isolates from intestinal carriers and liver abscess patients are closely related genotypically. Additionally, our findings suggest that environmental factors might play an important role in the intestinal colonization of these strains in Korean ethnicity. These findings may partially explain the geographical difference in the epidemiology of K. pneumoniae liver abscess.

References

Chung DR, Lee SS, Lee HR, Kim HB, Choi HJ, Eom JS, Kim JS, Choi YH, Lee JS, Chung MH, Kim YS, Lee H, Lee MS, Park CK (2007) Emerging invasive liver abscess caused by K1 serotype Klebsiella pneumoniae in Korea. J Infect 54:578–583

Ko WC, Paterson DL, Sagnimeni AJ, Hansen DS, von Gottberg A, Mohapatra S, Casellas JM, Goossens H, Mulazimoglu L, Trenholme G, Klugman KP, McCormack JG, Yu VL (2002) Community-acquired Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia: global differences in clinical patterns. Emerg Infect Dis 8:160–166

Fang FC, Sandler N, Libby SJ (2005) Liver abscess caused by magA + Klebsiella pneumoniae in North America. J Clin Microbiol 43:991–992

Rahimian J, Wilson T, Oram V, Holzman RS (2004) Pyogenic liver abscess: recent trends in etiology and mortality. Clin Infect Dis 39:1654–1659

Chung DR, Lee HR, Lee SS, Kim SW, Chang HH, Jung SI, Oh MD, Ko KS, Kang CI, Peck KR, Song JH (2008) Evidence for clonal dissemination of the serotype K1 Klebsiella pneumoniae strain causing invasive liver abscesses in Korea. J Clin Microbiol 46:4061–4063

Mizuta K, Ohta M, Mori M, Hasegawa T, Nakashima I, Kato N (1983) Virulence for mice of Klebsiella strains belonging to the O1 group: relationship to their capsular (K) types. Infect Immun 40:56–61

Lin JC, Chang FY, Fung CP, Xu JZ, Cheng HP, Wang JJ, Huang LY, Siu LK (2004) High prevalence of phagocytic-resistant capsular serotypes of Klebsiella pneumoniae in liver abscess. Microbes Infect 6:1191–1198

Blanchette EA, Rubin SJ (1980) Seroepidemiology of clinical isolates of Klebsiella in Connecticut. J Clin Microbiol 11:474–478

Cryz SJ Jr, Mortimer PM, Mansfield V, Germanier R (1986) Seroepidemiology of Klebsiella bacteremic isolates and implications for vaccine development. J Clin Microbiol 23:687–690

Jenney AW, Clements A, Farn JL, Wijburg OL, McGlinchey A, Spelman DW, Pitt TL, Kaufmann ME, Liolios L, Moloney MB, Wesselingh SL, Strugnell RA (2006) Seroepidemiology of Klebsiella pneumoniae in an Australian Tertiary Hospital and its implications for vaccine development. J Clin Microbiol 44:102–107

Kim JK, Chung DR, Wie SH, Yoo JH, Park SW (2009) Risk factor analysis of invasive liver abscess caused by the K1 serotype Klebsiella pneumoniae. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 28:109–111

Han SHB (1995) Review of hepatic abscess from Klebsiella pneumoniae. An association with diabetes mellitus and septic endophthalmitis. West J Med 162:220–224

Tomás JM, Ciurana B, Jofre JT (1986) New, simple medium for selective, differential recovery of Klebsiella spp. Appl Environ Microbiol 51:1361–1363

Struve C, Bojer M, Nielsen EM, Hansen DS, Krogfelt KA (2005) Investigation of the putative virulence gene magA in a worldwide collection of 495 Klebsiella isolates: magA is restricted to the gene cluster of Klebsiella pneumoniae capsule serotype K1. J Med Microbiol 54:1111–1113

Diancourt L, Passet V, Verhoef J, Grimont PA, Brisse S (2005) Multilocus sequence typing of Klebsiella pneumoniae nosocomial isolates. J Clin Microbiol 43:4178–4182

Podschun R, Pietsch S, Holler C, Ullmann U (2001) Incidence of Klebsiella species in surface waters and their expression of virulence factors. Appl Environ Microbiol 67:3325–3327

Struve C, Krogfelt KA (2004) Pathogenic potential of environmental Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates. Environ Microbiol 6:584–590

Favre-Bonté S, Licht TR, Forestier C, Krogfelt KA (1999) Klebsiella pneumoniae capsule expression is necessary for colonization of large intestines of streptomycin-treated mice. Infect Immun 67:6152–6156

Financial support

This work was supported by Samsung Biomedical Research Institute (SBRI) Grant, CA73091.

Potential conflict of interest

None of the authors had any conflicts.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chung, D.R., Lee, H., Park, M.H. et al. Fecal carriage of serotype K1 Klebsiella pneumoniae ST23 strains closely related to liver abscess isolates in Koreans living in Korea. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 31, 481–486 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-011-1334-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-011-1334-7