Abstract

This retrospective case–control study was undertaken to review the clinical features associated with heteroresistant vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus (hVISA) and vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus (VISA) infections and the local impact they have on clinical outcome. Compared with vancomycin-susceptible S. aureus (n = 30), hVISA and VISA infections (n = 10) are found to be associated with a longer period of prior glycopeptide use (P = 0.01), bone/joint (P < 0.01) and prosthetic infections (P = 0.04), as well as treatment failure, as evidenced by longer bacteremic (P < 0.01) and culture positivity (P < 0.01) periods. This was observed to have resulted in longer hospital length of stay (P < 0.01) and total antibiotic therapy duration (P = 0.01). There was, however, no significant difference in the overall patient mortality or the hospitalization cost (P = 0.12) in both groups. Clinicians should be cognizant of the association between hVISA/VISA with high bacterial load deep-seated infections. We recommend targeted and even universal screening for hVISA/VISA in methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) infections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Infections from methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) with reduced susceptibility to vancomycin have emerged in settings with high background MRSA endemicity. These strains include vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus (VISA; MIC [minimum inhibitory concentration] 4-8 μg/ml]) and heteroresistant vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus (hVISA) strains which are defined by the presence of subpopulations of MRSA with intermediate vancomycin resistance. Since the first reports in 1997 in Japan [1], there have been many more cases of hVISA and VISA reported globally. Given the previous lack of standardization of definitions of hVISA and VISA in the literature, their significance and impact on clinical outcome remain unclear. A Japanese paper showed a significant linear correlation between the vancomycin susceptibility of the initial MRSA strains and the initial therapeutic response [2]. hVISA infections have been found to be associated with high bacterial load infections and vancomycin treatment failure in an Australian study [3]. An Israeli experience reported high mortality rate and poor outcomes with hVISA infections, despite adequate vancomycin trough levels [4].

In Singapore public hospitals, 40% of S. aureus strains isolated are methicillin-resistant [5]. The vancomycin MIC for major clones of healthcare-associated MRSA is creeping up, with a mean MIC of 2.0 μg/ml [6]. In the same year that the Australians first reported hVISA in 2001 [7], hVISA was also isolated in Singapore in two patients. According to a local study in 2005, the estimated prevalence rate of hVISA causing persistent infections among all MRSA cases was 0.2% [8]. Since then, several more isolates of hVISA and VISA were detected on screening in the laboratory. A case–control study was undertaken to study the local impact of hVISA and VISA.

Methods

We identified all patients with persistent MRSA infections (defined by at least 1 week of persistent positive cultures from sterile sites for MRSA despite treatment) diagnosed by infectious disease physicians at Singapore General Hospital, a tertiary care institution, from 1st January 2005 to 31st December 2006. Prompted by the infectious diseases physicians, all of these MRSA isolates obtained from patients with persistent infections were screened by the microbiology laboratory for the presence of hVISA and VISA. For any particular patient, only the latest isolate in the laboratory was screened for hVISA and VISA, which may not necessarily be the very first isolate of MRSA. These screening procedures were otherwise not done routinely.

Method of hVISA screening

Etest macromethod (EMM) [9]. Colonies isolated from overnight growth on trypticase soy agar plate containing 5% sheep blood were inoculated into brain heart infusion (BHI) broth to achieve 2 McFarland turbidity. 200 μl of the suspension was dispensed onto BHI agar. Vancomycin and teicoplanin Etest strips were placed on the plate surface incubated at 35°C in ambient air and read at 24 and 48 h. hVISA was defined when vancomycin and teicoplanin MICs ≥ 8 μg/ml or teicoplanin MIC ≥ 12 μg/ml.

VISA definition

The vancomycin MIC of all MRSA isolates were determined using standard Etest methods [10]. The criterion for defining VISA is an MIC of 4-8 μg/ml, as defined by CLSI guidelines [10].

Demographics and baseline data retrieved from medical records included comorbidities, history of previous MRSA carriage, and recent surgery in the past 6 months. Clinical features and outcomes assessed included the site of infection, overall response to therapy (duration of culture positivity/bacteremia, length of hospital/ICU stay, survival at discharge and after 1 month), total antibiotic therapy duration, duration of glycopeptide use and mean vancomycin concentration prior to hVISA screening, delay in starting appropriate antibiotic, and hospitalization cost (which reflects the actual cost to the institution, including the total hospital, nursing, and medication costs accrued during the hospital admission). These findings were compared for the two groups to assess for significant associations. Continuous variables were assessed by independent samples t-test, while categorical variables were analyzed using Pearson’s Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test. Calculations were performed using SPSS software version 13 and a P-value of < 0.05 is considered as significant. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Results

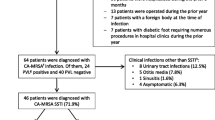

Fifty-six patients were deemed to have persistent MRSA infections, all of whose MRSA isolates were screened for the presence of hVISA and VISA. Cases were defined as patients with VISA or hVISA (n = 10; seven VISA, three hVISA). Thirty of the remaining 46 patients screened negative for hVISA and VISA were regarded as having vancomycin-sensitive MRSA (VS-MRSA) and were randomly assigned and analyzed as controls. The baseline characteristics of the cases were similar to the controls in terms of age, sex, previous MRSA carriage, and other comorbidities, except for controls having more malignancies than cases (P = 0.04) (Table 1). There were significantly more bone or joint infections amongst cases (P < 0.01) (Table 2). Similarly, infections involving prosthetic devices were more common amongst cases (P = 0.04). However, for the other sites of infection, there were no statistical differences between the two groups. Cases were exposed to a longer period of glycopeptide use prior to hVISA/VISA screening compared to controls (P = 0.01). (Note: two patients with VISA infections were treated with teicoplanin prior to hVISA screening.) Amongst the cases, only one patient continued to be treated with vancomycin, while the rest were either commenced on combination therapy (mostly with rifampicin) or switched to an alternative antibiotic, which was usually linezolid.

Cases were more likely to be associated with glycopeptide treatment failure, as evidenced by longer bacteremic (P < 0.01) and culture positivity (P < 0.01) periods. They also required a longer antibiotic treatment period (P = 0.01) and a longer hospital stay (P < 0.01). This was despite the fact that there was no significant delay in starting appropriate antibiotics in both groups (P = 0.48). Adequate mean vancomycin concentrations were also attained prior to hVISA/VISA screening in both groups of patients (10.9 vs. 12.2 μg/dL, P = 0.53). There was no significant difference in the overall patient mortality upon discharge and at 1 month between the two groups. As a result of the longer hospital stay, hVISA/VISA infections tended to incur higher hospitalization costs, although this did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.12).

Discussion

Our study reaffirms the findings by Charles et al. that hVISA/VISA infections are associated with high bacterial load infections, in particular bone/joint and prosthetic materials, and treatment failure [3]. Expectedly, it resulted in longer antibiotic treatment periods and longer hospitalization.

The prevalence of hVISA was found to be 5.4% (3/56) and VISA at 12.5% (7/56) amongst patients deemed to have persistent MRSA infections at our center. These rates are probably not representative of the actual burden of such infections, as only patients with persistent MRSA infections were studied. This contrasts the lower prevalence rate of hVISA highlighted in an earlier local study which compared hVISA cases with all MRSA cases and not just those with persistent infections [8]. Despite a similar ICU length of stay, the significant overall difference in length of stay would have been expected to impact adversely on the cost for the cases. However, the lack of such a cost impact may be due to factors such as controls having more comorbidities; after all, there were more malignancies in this group, which could escalate hospitalization costs. Hence, cost issues may have been confounded by the unmatching of cases and controls. In reality, there is a need for detailed cost analysis conducted from a societal and patient perspective in order to reflect the true cost burden of hVISA/VISA infections. For instance, indirect costs from outpatient antibiotic therapy, outpatient follow-up consultations, transport costs, and costs relating to loss of productivity were all not included in our cost analysis, but could have impacted it. This study was also not designed to evaluate detailed cost analysis as a primary endpoint and, therefore, was not empowered as such.

Inadequate glycopeptide therapy was observed to be associated with clinical failure in previous studies. However, this was not found in our study, since there was no significant difference in delay in instituting appropriate antibiotic treatment and vancomycin trough levels were similar in both groups. Nevertheless, we did find an association of hVISA/VISA infections with a longer period of prior glycopeptide use. The question arises as to whether prolonged glycopeptide use could predispose to the evolution of S. aureus with reduced glycopeptide susceptibility. A study by Sakoulas et al. [11] showed that MRSA had a propensity to evolve into an hVISA phenotype on exposure in vitro to subinhibitory concentrations of vancomycin; this was not observed in vivo after prolonged vancomycin. However, vancomycin tolerance and reduced killing in vivo was noted. There is also a rise in vancomycin MICs in staphylococcal strains from biofilms [12]. Perhaps vancomycin itself may not be efficacious enough, especially for serious infections, given its poor tissue penetration and relatively weak antibacterial activity [13].

Contrary to the findings of a recent study by Maor et al. which showed a mortality rate of 75% for hVISA patients (50% hVISA-attributable mortality) [4], our study showed no significant impact on mortality at discharge and 1 month later. However, MRSA with reduced susceptibility does not appear, at least in our experience, to be any less virulent than MRSA without reduced susceptibility. With a sensitivity and specificity comparable to that of population analysis profiling, EMM was employed as the tool to screen for hVISA, as others have done [4].

This study has limitations however. Screening for hVISA/VISA was prompted by infectious diseases physicians involved in the care of patients with persistent infections. Such a selective screening process would naturally not be all-encompassing, adversely impacting on the true prevalence and clinical impact of hVISA/VISA. The small sample size (n = 10 cases, 30 controls) and retrospective design of our study will require validation of its results with a prospective study. In our study, hVISA and VISA cases were analyzed collectively in view of the small numbers, and both groups shared similar profiles.

This study has the following implications. First, clinicians should be aware of the association between hVISA/VISA with bone, joint, or prosthetic joint infections. Within reasonable limits, all implicated hardware should be removed promptly. Inadequate source control coupled with the limitations of vancomycin will lead to treatment failure. Second, all bone-, joint-, and implant-related MRSA infections should arguably be screened for hVISA/VISA. Considering our high MRSA endemicity rates and vancomycin MIC creep [5, 6], the universal screening of all MRSA isolates for hVISA/VISA may also be warranted. Close communication between clinicians and laboratory staff is crucial to ensure that persistent MRSA infections are screened for hVISA/VISA. Finally, the prevalence of hVISA/VISA as determined in this study suggests a ‘tip of the iceberg’ phenomenon. A more permissive rather than targeted screening may reveal a greater burden. This is highly relevant because these organisms pose significant infection control threats.

References

Hiramatsu K, Aritaka N, Hanaki H, Kawasaki S, Hosoda Y, Hori S, Fukuchi Y, Kobayashi I (1997) Dissemination in Japanese hospitals of strains of Staphylococcus aureus heterogeneously resistant to vancomycin. Lancet 350:1670–1673. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(97)07324-8

Neoh HM, Hori S, Komatsu M, Oguri T, Takeuchi F, Cui LZ, Hiramatsu K (2007) Impact of reduced vancomycin susceptibility on the therapeutic outcome of MRSA bloodstream infections. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 6:13. doi:10.1186/1476-0711-6-13

Charles PGP, Ward PB, Johnson PDR, Howden BP, Grayson ML (2004) Clinical features associated with bacteremia due to heterogeneous vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Infect Dis 38:448–451. doi:10.1086/381093

Maor Y, Rahav G, Belausov N, Ben-David D, Smollan G, Keller N (2007) Prevalence and characteristics of heteroresistant vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia in a tertiary care center. J Clin Microbiol 45:1511–1514. doi:10.1128/JCM.01262-06

Hsu LY, Loomba-Chlebicka N, Koh YL, Tan TY, Krishnan P, Lin RT, Tee NW, Fisher DA, Koh TH (2007) Evolving EMRSA-15 epidemic in Singapore hospitals. J Med Microbiol 56(Pt 3):376–379. doi:10.1099/jmm.0.46950-0

Hsu LY, Koh TH, Singh K, Kang ML, Kurup A, Tan BH (2005) Dissemination of multisusceptible methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Singapore. J Clin Microbiol 43(6):2923–2925. doi:10.1128/JCM.43.6.2923-2925.2005

Ward PB, Johnson PDR, Grabsch EA, Mayall BC, Grayson ML (2001) Treatment failure due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) with reduced susceptibility to vancomycin. Med J Aust 175:480–483

Sng LH, Koh TH, Wang GC, Hsu LY, Kapi M, Hiramatsu K (2005) Heterogeneous vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (hetero-VISA) in Singapore. Int J Antimicrob Agents 25:177–179. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2004.11.001

Wootton M, MacGowan AP, Walsh TR, Howe RA (2007) A multicenter study evaluating the current strategies for isolating Staphylococcus aureus strains with reduced susceptibility to glycopeptides. J Clin Microbiol 45(2):329–332. doi:10.1128/JCM.01508-06

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) (2006) Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Sixteenth informational supplement. M100- S16. CLSI, Wayne, PA

Sakoulas G, Gold HS, Cohen RA, Venkataraman L, Moellering RC, Eliopoulos GM (2006) Effects of prolonged vancomycin administration on methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in a patient with recurrent bacteraemia. J Antimicrob Chemother 57:699–704. doi:10.1093/jac/dkl030

Williams I, Venables WA, Lloyd D, Paul F, Critchley I (1997) The effects of adherence to silicone surfaces on antibiotic susceptibility in Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiology 143:2407–2413

Deresinski S (2007) Counterpoint: Vancomycin and Staphylococcus aureus—an antibiotic enters obsolescence. Clin Infect Dis 44(12):1543–1548. doi:10.1086/518452

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fong, R.K.C., Low, J., Koh, T.H. et al. Clinical features and treatment outcomes of vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus (VISA) and heteroresistant vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus (hVISA) in a tertiary care institution in Singapore. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 28, 983–987 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-009-0741-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-009-0741-5