Abstract

Enterococci are an increasingly important cause of nosocomial infections. While the clinical impact of enterococci in cases of bacteremia and super-infections in selected patient populations has been well-established, their role as primary pathogens in polymicrobial intra-abdominal infections remains controversial. While it has been suggested that the presence of enterococci increases the rate of infectious post-operative complication, it has also been demonstrated that polymicrobial intra-abdominal infections involving enterococci can be treated successfully with appropriate surgical drainage and antibiotics, such as cephalosporins, that are not active against enterococci. Therefore, the question arises of whether or not antibiotic coverage against enterococci should be included in the empirical treatment of peritonitis in certain high-risk patient populations. An extensive literature review revealed some evidence arguing in favour of using empirical therapy with enterococcal coverage for intra-abdominal infections in the following cases: (i) immunocompromised patients with nosocomial, post-operative peritonitis; (ii) patients with severe sepsis of abdominal origin who have previously received cephalosporins and other broad-spectrum antibiotics selecting for Enterococcus spp.; (iii) patients with peritonitis and valvular heart disease or prosthetic intravascular material, which place them at high risk of endocarditis. The ideal therapeutic regimen for these high-risk patients remains to be determined, but empirical therapy directed against enterococci should be considered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Peritonitis is a frequent and life-threatening disease [1]. During the last century, however, great progress has been made in the management of this condition [2]. Although antimicrobial treatment has certainly helped to improve patient outcome [3, 4], adequate source control by early surgical intervention remains the cornerstone of treatment [5, 6].

While enterococci are an increasingly important cause of nosocomial infections, their clinical significance in peritonitis has been the subject of a long-lasting and ongoing debate [7, 8, 9, 10, 11]. Several recent articles have attempted to better delineate the profile of patient populations at high risk of invasive enterococcal peritonitis and have suggested that empiric anti-enterococcal coverage in these patients may be beneficial [12, 13]. Based on a selection of relevant articles, the present review attempts to summarise published evidence arguing in favour of empiric anti-enterococcal coverage in selected patient groups. More specifically, the following questions are addressed: (i) What basic coverage is absolutely needed in the empiric therapy of peritonitis? (ii) Are enterococci able to cause treatment failures and adverse outcomes in patients with intra-abdominal infection? (iii) Which surgical patients are at risk of enterococcal bacteremia? (iv) What is the potential impact of inadequate enterococcal coverage in septic high-risk patients? (v) What is the profile of patients for whom empiric enterococcal coverage should be advocated?

What Basic Coverage is Required for Empiric Therapy of Peritonitis?

The goals of antimicrobial therapy in the treatment of peritonitis are as follows: (i) to prevent the local spread of existing infection in the early phase; (ii) to control bacteremia and avoid distant hematogenous spread (e.g. hepatic abscess); and (iii) to reduce late complications after bacterial intra-abdominal contamination (e.g. post-operative abscess). In cases of secondary peritonitis, empiric antibiotic regimens should at least include coverage of aerobic gram-negative bacteria in order to decrease early mortality induced by bacterial endotoxins causing septic shock; they should also include coverage of anaerobic microorganisms to prevent the development of late post-operative abscesses [10, 14]. Several clinical studies performed in the 1970s showed that in the absence of adequate anti-anaerobic coverage, the late complication rate after intra-abdominal infection was high, with an incidence of post-operative abscesses of up to 30% [15, 16].

Ample evidence suggests that complicated, community-acquired intra-abdominal infections involving mixed flora can be treated with surgery and different classes of antibiotics without consistent anti-enterococcal activity (e.g. cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones) [11, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23]. For example, a review of six clinical trials examining the use of antibiotics without in-vitro activity against enterococci in the treatment of intra-abdominal infections noted no cases of treatment failure due to Enterococcus spp., despite the fact that 20–30% of cultures grew enterococci [10]. Thus, the frequent practice of adding ampicillin or penicillin to cover enterococcal infection is not justified in most cases. Conventional wisdom even argues against the necessity of adding anti-enterococcal coverage if initial intra-peritoneal cultures showed enterococcal growth [9].

Are Enterococci Able to Cause Treatment Failures and Adverse Outcomes in Patients with Intra-Abdominal Infection?

While the clinical impact of antibiotic-resistant enterococci in bacteremia and super-infections in selected patient populations (e.g., burn patients with infections due to vancomycin-resistant enterococci) has been well established [24, 25], the role of antibiotic-susceptible enterococci as primary pathogens in polymicrobial intra-abdominal infections is still controversial. Animal models have shown that monomicrobial, intra-abdominal enterococcal infections have limited pathogenicity, since the organism lacks virulence and the capacity to induce late abscess formation [26, 27]. It has been postulated that enterococci may express bacterial synergy and pro-inflammatory activity only in the presence of more virulent bacteria by inhibiting phagocytosis and intracellular killing of those primary pathogens [28].

Clinical data about the harmful effect of enterococcal peritonitis is also limited, since many types of organisms are usually cultured from intra-abdominal infections. A case series published 2 decades ago analysed enterococcal breakthrough sepsis in 19 surgical patients and found a crude case-fatality rate of 68% [29]. In 1995, the secondary analysis of a randomised clinical trial involving 330 patients postulated that the presence of Enterococcus spp. may be a marker for a complicated course in hospitalised patients with peritonitis and that the presence of this microorganism was associated with a higher likelihood of treatment failure [30].

More recent studies have suggested that the presence of enterococci increases the infectious post-operative complication rate and even the risk of death [12, 13]. For instance, Sitges-Serra et al. [13] have looked at post-operative enterococcal infections after treatment of complicated intra-abdominal sepsis. They found a high proportion (50%; n=34) of enterococci in post-operative peritonitis. Independent risk factors for enterococcal infection were tertiary peritonitis, high severity of illness and inappropriate empirical antibiotic coverage against enterococci. Post-operative enterococcal infections were associated with higher mortality (21% vs. 4%; P<0.001). The authors of this study concluded that empirical antibiotic therapy covering enterococci “should be contemplated in some circumstances” [13]. Table 1 summarises the different types of studies that have investigated potential adverse outcomes associated with enterococcal intra-abdominal infection.

Which Surgical Patients Are at Risk of Enterococcal Bacteremia?

Most authorities agree that enterococcal bacteremia is a clinical condition requiring adequate antibiotic treatment, since serious adverse outcomes can arise [24]. In one case series, 15% of all episodes of nosocomial enterococcal bacteremia were complicated by endocarditis [31]. Therefore, the following question arises: Have previous investigations already pre-defined the risk profile of surgical patients at high risk of enterococcal bacteremia? Surprisingly, although many studies have analysed the risk factors for vancomycin-resistant enterococcal infections [32, 33, 34] or the risk factors for enterococcal bacteremia in hospital-wide studies [35, 36, 37], few studies have analysed in detail the risk factors for enterococcal bacteremia in surgical patients [38]. For instance, Barrall et al. [39] performed a descriptive cohort study without multivariable analysis and found that enterococcal bacteremia was preceded by antibiotic use, exposure to central-venous catheters, other-organism bacteremia and intra-abdominal operations. Clearly, more precise and well-conducted studies are needed to better delineate the risk profile of patients undergoing general surgery who are at high risk of enterococcal bacteremia.

Immunocompromised patients permanently exposed to the health-care setting are at high risk of enterococcal bacteremia. It is a frequent infectious complication in liver transplant patients having previously received selective bowel decontamination, as previously shown by Patel et al. [40]. In their large cohort study, among 405 liver transplant patients, 114 had bacteremia with any type of microorganism and 52 had enterococcal bacteremia (incidence, 13%).

What Is the Potential Impact of Inadequate Enterococcal Coverage in High-Risk Patients with Enterococcal Sepsis?

Antibiotic selection pressure increases the risk of enterococcal super-infection and bacteremia either with drug-susceptible or -resistant strains [34]. Enterococcal super-infection may be prevented by avoiding prolonged prophylactic or broad-spectrum therapeutic regimens (such as those with cephalosporins) that lack anti-enterococcal activity [41]. In cases of enterococcal sepsis in critically ill patients, inadequate empiric antibiotic therapy may increase the risk of death. As shown in a prospective multicentre study among patients with monomicrobial enterococcal bacteremia, the receipt of effective anti-enterococcal therapy within 48 hours independently predicted survival (odds ratio [OR] for death, 0.21; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.06–0.80) [24].

We performed a secondary analysis of a randomised clinical trial of 904 patients with microbiologically documented severe sepsis and found that inadequate antimicrobial treatment of severe sepsis of abdominal origin (n=123) was associated with a significantly increased risk of death after adjusting for confounding factors (OR, 2.8; 95%CI, 1.3–5.9); inadequately treated enterococcal infection contributed to this increased risk [42]. Certainly, new diagnostic approaches and interventions aimed at improving the detection and treatment of early gram-positive sepsis are urgently needed.

What Is the Profile of Patients for Whom Empiric Enterococcal Coverage Should Be Advocated?

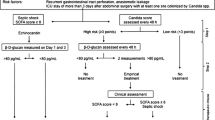

Figure 1 summarises a tentative proposal of those highly selected patients who may benefit from empiric anti-enterococcal coverage in case of secondary or tertiary peritonitis. Although empiric therapy directed at enterococci may not always be necessary, reasonable indications for specific therapy include the presence of septic shock in patients pre-treated with cephalosporins, immunosuppressed patients at high risk of bacteremia, presence of prosthetic heart valves, or persistent or recurrent intra-abdominal infection with signs of severe sepsis.

Presentation of an Exemplary Case History in which Empiric Anti-Enterococcal Therapy for Peritonitis was Considered Adequate and Beneficial

In June 2003, an 86-year-old female patient with a history of type II diabetes, severe post-rheumatic valvulopathy and secondary pulmonary arterial hypertension experienced a first episode of moderate diverticulitis. She was treated as an outpatient with 2 g of ceftriaxone i.v./day for 10 days without anaerobic coverage. After initial improvement, the patient was hospitalised 2 months later with symptoms of lower abdominal pain, fever (38°C) and leukocytosis (18.5 G/l). On admission, there was no peritonitis, but clinical exam revealed a recto-vaginal fistula. An abdominal computed tomography scan showed multiple small abscesses.

The patient refused surgical treatment and was treated empirically with a combination of ceftriaxone and metronidazole. Blood cultures grew Escherichia coli sensitive to ceftriaxone. Despite antibiotic treatment, on day 9 of hospitalisation she developed signs of peritonitis and severe sepsis. Antibiotic treatment was immediately changed to a broad-spectrum regimen covering Enterococcus faecalis, the presence of which was confirmed 4 days later in two sets of blood cultures. The patient improved and was discharged 18 days later without surgical intervention. This case shows that empiric anti-enterococcal coverage may be warranted and beneficial in the presence of risk factors for enterococcal super-infection and endocarditis.

Conclusions

Enterococcal infections are becoming increasingly prevalent, because of the widespread use of cephalosporins, often neglected environmental reservoirs in the hospital setting, and a greater number of immunosuppressed patients [43]. Although many invasive enterococcal infections are of intra-abdominal origin, the pathogenic role of Enterococcus spp. in peritonitis remains controversial. Many studies have demonstrated that polymicrobial intra-abdominal infections that contain enterococci can be treated successfully with appropriate surgical drainage and antibiotics such as cephalosporins that are not active against enterococci. Therefore, in the recently published IDSA-guidelines for the selection of antibiotic therapy for complicated intra-abdominal infections, strong evidence was cited against routine coverage of Enterococcus spp. in community-acquired intra-abdominal infections [14].

In contrast, there is some evidence (although of rather weak quality) to justify the use of empiric antibiotic therapy covering enterococci in post-operative, nosocomial peritonitis in certain high-risk patient populations. Based on the literature review presented here, we found evidence arguing in favour of using empirical enterococcal coverage in the treatment of intra-abdominal infections in the following cases: (i) immunocompromised patients with nosocomial, post-operative peritonitis; (ii) patients with severe sepsis of abdominal origin who have previously received cephalosporins or other broad-spectrum antibiotics selecting for Enterococcus spp.; (iii) patients with peritonitis and valvular heart disease or prosthetic intravascular material, which may increase the risk of enterococcal endocarditis.

The ideal therapeutic regimen for these high-risk patients remains to be determined, but empirical therapy directed against enterococci should be considered. Extended-spectrum penicillins with anaerobic coverage may be effective empiric regimens for those selected cases, since they offer adequate therapy for mixed intra-abdominal infections. In cases of confirmed enterococcal bacteremia (without vancomycin resistance), patients should be treated with bactericidal, combination antibiotic therapy including a penicillin and an aminoglycoside.

References

Skau T, Nystrom PO, Carlsson C (1985) Severity of illness in intra-abdominal infection. A comparison of two indexes. Arch Surg 120:152–158

Bohnen JM (1992) Operative management of intra-abdominal infections. Infect Dis Clin North Am 6:511–523

Gorecki PJ, Schein M, Mehta V, Wise L (2000) Surgeons and infectious disease specialists: different attitudes towards antibiotic treatment and prophylaxis in common abdominal surgical infections. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 1:115–123; discussion 125–126

Harbarth S, Ferriere K, Hugonnet S, Ricou B, Suter P, Pittet D (2002) Epidemiology and prognostic determinants of bloodstream infections in surgical intensive care. Arch Surg 137:1353–1359

Bohnen J, Boulanger M, Meakins JL, McLean AP (1983) Prognosis in generalized peritonitis. Relation to cause and risk factors. Arch Surg 118:285–290

Mulier S, Penninckx F, Verwaest C, et al (2003) Factors affecting mortality in generalized postoperative peritonitis: multivariate analysis in 96 patients. World J Surg 27:379–384

Dougherty SH (1984) Role of enterococcus in intraabdominal sepsis. Am J Surg 148:308–312

Barie PS, Christou NV, Dellinger EP, Rout WR, Stone HH, Waymack JP (1990) Pathogenicity of the enterococcus in surgical infections. Ann Surg 212:155–159

Nichols RL, Muzik AC (1992) Enterococcal infections in surgical patients: the mystery continues. Clin Infect Dis 15:72–76

Gorbach SL (1993) Intraabdominal infections. Clin Infect Dis 17:961–965

Rohrborn A, Wacha H, Schoffel U, et al (2000) Coverage of enterococci in community acquired secondary peritonitis: results of a randomized trial. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 1:95–107

Sotto A, Lefrant JY, Fabbro-Peray P, et al (2002) Evaluation of antimicrobial therapy management of 120 consecutive patients with secondary peritonitis. J Antimicrob Chemother 50:569–576

Sitges-Serra A, Lopez MJ, Girvent M, Almirall S, Sancho JJ (2002) Postoperative enterococcal infection after treatment of complicated intra-abdominal sepsis. Br J Surg 89:361–367

Solomkin JS, Mazuski JE, Baron EJ, et al (2003) Guidelines for the selection of anti-infective agents for complicated intra-abdominal infections. Clin Infect Dis 37:997–1005

Thadepalli H, Gorbach SL, Broido PW, Norsen J, Nyhus L (1973) Abdominal trauma, anaerobes, and antibiotics. Surg Gynecol Obstet 137:270–276

Berne TV, Yellin AW, Appleman MD, Heseltine PN (1982) Antibiotic management of surgically treated gangrenous or perforated appendicitis. Comparison of gentamicin and clindamycin versus cefamandole versus cefoperazone. Am J Surg 144:8–13

Berne TV, Yellin AE, Appleman MD, Gill MA, Chenella FC, Heseltine PN (1987) Surgically treated gangrenous or perforated appendicitis. A comparison of aztreonam and clindamycin versus gentamicin and clindamycin. Ann Surg 205:133–137

Berne TV, Yellin AE, Appleman MD, Heseltine PN, Gill MA (1993) A clinical comparison of cefepime and metronidazole versus gentamicin and clindamycin in the antibiotic management of surgically treated advanced appendicitis. Surg Gynecol Obstet 177 (Suppl):18–22

Solomkin JS, Reinhart HH, Dellinger EP, et al (1996) Results of a randomized trial comparing sequential intravenous/oral treatment with ciprofloxacin plus metronidazole to imipenem/cilastatin for intra-abdominal infections. The Intra-Abdominal Infection Study Group. Ann Surg 223:303–315

Quinn JP (1997) Rational antibiotic therapy for intra-abdominal infections. Lancet 349:517–518

Jaccard C, Troillet N, Harbarth S, et al (1998) Prospective randomized comparison of imipenem-cilastatin and piperacillin-tazobactam in nosocomial pneumonia or peritonitis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 42:2966–2972

Zanetti G, Harbarth SJ, Trampuz A, et al (1999) Meropenem (1.5 g/day) is as effective as imipenem/cilastatin (2 g/day) for the treatment of moderately severe intra-abdominal infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents 11:107–113

Teppler H, McCarroll K, Gesser RM, Woods GL (2002) Surgical infections with enterococcus: outcome in patients treated with ertapenem versus piperacillin-tazobactam. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 3:337–349

Vergis EN, Hayden MK, Chow JW, et al (2001) Determinants of vancomycin resistance and mortality rates in enterococcal bacteremia. A prospective multicenter study. Ann Intern Med 135:484–492

Carmeli Y, Eliopoulos G, Mozaffari E, Samore M (2002) Health and economic outcomes of vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Arch Intern Med 162:2223–2228

Onderdonk AB, Bartlett JG, Louie T, Sullivan-Seigler N, Gorbach SL (1976) Microbial synergy in experimental intra-abdominal abscess. Infect Immun 13:22–26

Dupont H, Montravers P, Mohler J, Carbon C (1998) Disparate findings on the role of virulence factors of Enterococcus faecalis in mouse and rat models of peritonitis. Infect Immun 66:2570–2575

Montravers P, Mohler J, Saint Julien L, Carbon C (1997) Evidence of the proinflammatory role of Enterococcus faecalis in polymicrobial peritonitis in rats. Infect Immun 65:144–149

Dougherty SH, Flohr AB, Simmons RL (1983) ‘Breakthrough’ enterococcal septicemia in surgical patients. Arch Surg 118:232–238

Burnett RJ, Haverstock DC, Dellinger EP, et al (1995) Definition of the role of enterococcus in intraabdominal infection: analysis of a prospective randomized trial. Surgery 118:716–721

Fernandez-Guerrero ML, Herrero L, Bellver M, Gadea I, Roblas RF, Gorgolas M de (2002) Nosocomial enterococcal endocarditis: a serious hazard for hospitalized patients with enterococcal bacteraemia. J Intern Med 252:510–515

Lautenbach E, Bilker WB, Brennan PJ (1999) Enterococcal bacteremia: risk factors for vancomycin resistance and predictors of mortality. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 20:318–323

Carmeli Y, Samore MH, Huskins C (1999) The association between antecedent vancomycin treatment and hospital-acquired vancomycin-resistant enterococci: a meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 159:2461–2468

Harbarth S, Cosgrove S, Carmeli Y (2002) Effects of antibiotics on nosocomial epidemiology of vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 46:1619–1628

Pallares R, Pujol M, Pena C, Ariza J, Martin R, Gudiol F (1993) Cephalosporins as risk factor for nosocomial Enterococcus faecalis bacteremia. A matched case-control study. Arch Intern Med 153:1581–1586

Gray J, Marsh PJ, Stewart D, Pedler SJ (1994) Enterococcal bacteraemia: a prospective study of 125 episodes. J Hosp Infect 27:179–186

Noskin GA, Peterson LR, Warren JR (1995) Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus faecalis bacteremia: acquisition and outcome. Clin Infect Dis 20:296–301

Mainous MR, Lipsett PA, O’Brien M (1997) Enterococcal bacteremia in the surgical intensive care unit. Does vancomycin resistance affect mortality? Arch Surg 132:76–81

Barrall DT, Kenney PR, Slotman GJ, Burchart KW (1985) Enterococcal bacteremia in surgical patients. Arch Surg 120:57–63

Patel R, Badley AD, Larson-Keller J, et al (1996) Relevance and risk factors of enterococcal bacteremia following liver transplantation. Transplantation 61:1192–1197

Harbarth S, Samore MH, Lichtenberg D, Carmeli Y (2000) Prolonged antibiotic prophylaxis after cardiovascular surgery and its effect on surgical site infections and antimicrobial resistance. Circulation 101:2916–2921

Harbarth S, Garbino J, Pugin J, Romand J, Lew D, Pittet D (2003) Inappropriate initial antimicrobial therapy and its effect on survival in a clinical trial of immunomodulating therapy for severe sepsis. Am J Med 115:529–535

Harbarth S, Albrich W, Goldmann DA, Huebner J (2001) Control of multiply resistant cocci: do international comparisons help? Lancet Infect Dis 1:251–261

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This work was presented in part at the 43rd Annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy in Chicago, USA, September 2003 (Abstract #2079)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Harbarth, S., Uckay, I. Are there Patients with Peritonitis Who Require Empiric Therapy for Enterococcus?. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 23, 73–77 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-003-1078-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-003-1078-0