Abstract

Falls among persons with Parkinson’s disease (PD) often result in activity limitations, participation restrictions, social isolation or premature mortality. The purpose of this 1-year follow-up study was to compare potential differences in features of PD attributing to falls in relation to fall location (outdoor vs. indoor). We recruited 120 consecutive persons with PD who denied having fallen in the past 6 months. Disease stage and severity was assessed using the Hoehn and Yahr scale and the newer version of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale. Occurrence of falling and characteristics of falls was followed for 1 year. Results were assessed statistically. Outdoor falls were more commonly preceded by the extrinsic factors (tripping and slipping). Slipping was more common outdoors (p = 0.001). Indoor falls were mostly preceded by the intrinsic factors (postural instability, lower extremity weakness, vertigo). Vertigo was more common indoors (p = 0.006). Occurrence of injuries was more common after outdoor falls (p = 0.001). Indoor falls resulted in contusions only, while outdoor falls resulted in lacerations and fractures as well. In the regression model adjusted for age, disease duration, on/off phase during fall, Hoehn and Yahr stage of disease and levodopa dosage, slipping was associated with outdoor falling (odds ratio = 17.25, 95 % confidence interval 3.33–89.20, p = 0.001). These findings could be used to tailor fall prevention program with emphasis on balance recovery and negotiation of objects in environment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Falling is one of the most disabling features of Parkinson’s disease (PD) [1]. Falls among persons with PD often result in activity limitations, participation restrictions, social isolation or premature mortality [2]. Furthermore, over 9 years of follow-up a 51 % increase in risk of injury mortality has been documented [3]. Extensive epidemiological research has demonstrated that poor standing balance, motor-issues and brain-related changes, depression and fear of falling represent risk factors for falls in PD [4–7].

Considering heterogeneity of risk factors for falling, only a small proportion of falls among persons with PD result from an obvious, single cause [8]. To differentiate conditions in which a fall occurs, a distinction of intrinsic and extrinsic risk factors has been proposed [9]. Intrinsic (or patient-related) causes include dizziness/vertigo, syncope, lower extremity weakness and concomitant chronic conditions (cardiovascular diseases, poor vision and hearing) as well as medication adverse effects among persons with PD. Extrinsic factors are related to surrounding space and include environmental factors such as tripping, slipping, walking on uneven surfaces and inadequate illumination. Although both postural instability and freezing of gait have been commonly cited as causes of falls among persons with PD [4, 6] environmental factors should also be considered [10].

Differences in risk factors for outdoor and indoor falls in PD have rarely been investigated. In our previous research, using a cross-sectional study design, we observed that risk factors for falls in PD vary considerably by location [11]. Namely, outdoor falls were almost eight times more likely caused by extrinsic factor (tripping), while indoor falls were approximately five times more likely caused intrinsic factors (lower extremity weakness and internal sense of sudden loss of balance) [11]. The objective of the present 1-year of follow-up study was to compare potential differences in features of PD attributing to falls in relation to fall location (outdoor vs. indoor).

Materials and methods

Selection of participants

From August 15, 2011 to December 15, 2012, 120 consecutive persons with PD, who denied having fallen in the past 6 months, were recruited at the Department of Movement Disorders, Neurology Clinic, Clinical center of Serbia in Belgrade. To ensure that persons with PD were mobile and independent at least around their living space the following inclusion criteria were set: ability to walk independently for at least 10 m and ability to statically stand for at least 90 s. To eliminate potential walking difficulties and participation restrictions, influenced by other impairments or disabilities that could have facilitated falling at the time of fall, exclusion criteria were the following: presence of other neurologic (e.g. stroke, traumatic brain injuries, dementia) as well as psychiatric (e.g. psychoses), visual, audio-vestibular and orthopedic impairments (e.g. fracture, moderate to severe osteoarthritis). Participants signed an informed consent prior to enrollment in the study.

Measurement instruments

Demographic (age, gender, marital status, education level) and clinical (age at onset, duration of PD) characteristics were taken from the medical records of the Neurology Clinic. The PD diagnosis was made according to the United Kingdom Parkinson’s Disease Society (UK-PDS) Brain Bank criteria [12]. Disease stage and severity was assessed using the Hoehn and Yahr scale (HY) [13] and the newer version of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) [14]. Cognitive status was assessed by Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) [15] and only those with a score ≥24 were included (i.e. those without cognitive impairment). Dosages of levodopa were calculated based upon the systematic review of levodopa dose equivalency reporting in PD [16].

Follow-up and registration of falls

A fall was defined as an event which results in an individual coming to rest inadvertently on the ground/floor. Circumstances of falls were based upon patient diary and verbal information. After the follow-up period, descriptions were analyzed and to facilitate classification of circumstances falls, they were categorized according to description into tripping, slipping, postural instability, lower extremity weakness, vertigo/dizziness and freezing of gait. Occurrence of falling was followed for 1 year. Each subject was given a “fall diary” at enrolment with the aim at writing characteristics of the fall as soon as possible after falling. To ensure that persons with PD report their falls, regardless of whether they filled in the diaries or not, we contacted all 120 patients each month during 1 year of follow-up. Therefore, all falls and their particular characteristics were obtained through detailed telephone interviews, despite having received fall diaries of approximately 40 % of participants.

Falls were classified according to location as indoor or outdoor falls. An indoor fall was defined as occurring inside any building, while an outdoor fall was defined as occurring outside a building (including front and back garden, patio, porch, deck or outdoor stairs). Other aspects of the latest fall were investigated: time of day (daytime/evening and night), footwear (shoes, barefoot), PD phase (on/off), circumstance preceding the fall and specific situation that led to falling. Specifically, circumstances were grouped as extrinsic factors (such as tripping, slipping) and intrinsic factors that comprised postural instability, dizziness, sudden loss of strength in lower extremities (i.e. muscles giving away) and freezing of gait. Postural instability was defined as involuntary movement of the body either forward (anteropulsion), backward (retropulsion) or to the side (lateropulsion). Participants explained postural instability in their own words, usually describing it as “I felt that something pulled me to the side” or “It was as if something pushed me up front”. Participants were asked whether or not they needed an assistance to stand up and whether or not they sought medical treatment after falling. In addition, injury type was logged based on self-report and previous medical reports. After 1 year, seven patients (5.8 %) were lost to follow-up: one patient died, one patient moved abroad after 8 months, while five were not reachable over telephone.

Data analysis

Proportions were used to describe frequencies in categories of indoor and outdoor falls. Chi square test and Fischer’s exact test were used to assess the differences between various categories off falls. Logistic regression model was used to evaluate factors associated with location of falls. Dependent variable in the models was the location of fall (indoor = 1, outdoor = 2). Independent variables were categories of circumstances of falls. Because of potential confounding effects of age, PD duration, on/off phase, HY stage and levodopa dosage, the model was adjusted for these five variables (in the model they were assigned as independent variables). Probability level of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. We used statistical analysis the SPSS 17.0 statistical software package (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA) in data analysis.

Results

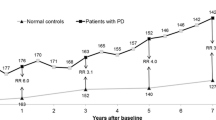

Basic demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1. Male to female ratio was 2:1. Median age was 60 years (age range 29–79). Median HY stage was 2 (Table 1). Over 1 year of follow-up 42 persons with PD (35.0 %) reported altogether 272 falls. Frequency of recurrent falls varied from 2 to 17, while one person reported a total of 153 falls over the period of 1 year. Characteristics of this person as well as characteristics of falls sustained during follow-up were omitted from further analysis as outliers. Therefore, we analyzed characteristics of 119 falls sustained by 41 persons with PD. Twenty-five persons (61.0 %) sustained 73 indoor falls, and 28 persons (68.3 %) sustained 46 outdoor falls. Frequency of outdoor falls ranged from 1 to 6, while frequency of indoor falls ranged from 1 to 16.

Both indoor and outdoor falls dominantly occurred in daytime (Table 2). Most persons with PD were in on phase at the time of fall. Outdoor falls were more commonly preceded by the extrinsic factors (tripping and slipping). Slipping was significantly more common outdoors. Indoor falls were mostly preceded by the intrinsic factors (postural instability, lower extremity weakness, vertigo). Vertigo was significantly more common indoors. There were no differences in terms of assistance to get up, seeking medical attention and hospitalization between indoor and outdoor falls (Table 2).

Distribution of injuries differed according to location of fall (Table 3). Overall, occurrence of injuries was significantly more common after outdoor falls. Indoor falls resulted in contusions only, while outdoor falls resulted in lacerations and fractures as well. Over the period of follow-up two fractures occurred (4.3 % of all outdoor falls). The first one was the hip fracture, occurred after lateropulsion. The other was radial fracture (fractura radii loco typico), occurred after breaking of a wooden step at the house entrance. Both fractures were sustained by women.

In logistic regression model we observed that slipping was strongly associated with outdoor falling (Table 4).

Discussion

Our previous papers described circumstances of falls according to frequency and location in the population of persons with PD, who experienced falls in past 6 months [11, 17]. This reports represent similar assessments, however, we used different methodological approach (current prospective cohort versus previous cross-sectional study) [11]. To our knowledge, this is the first prospective assessment of falls according to location among persons with PD. We observed that during 1 year of follow-up, overall indoor falls were more common compared with outdoor falls. Previously, we found that outdoor falls were slightly more frequent than indoor falls (57.2 vs. 47.8 %) [11]. Causes of falls in our respondents involved both extrinsic and intrinsic factors. In the present prospective study, predictor of outdoor falls was slipping. These findings are slightly different from our previous study (circumstances of falls were assessed in a retrospective manner), where tripping was predictor of outdoor falls, whereas predictors of indoor falls were lower extremity weakness and sudden loss of balance [11].

Slipping was strongly associated with outdoor falling when adjusted for several potential confounding factors. Outdoor slips are common after walking on wet pavement or grass. Moreover, outdoor slipping has been attributed to weather conditions and low air temperatures [18]. In older population slips commonly occur when walking over wet concrete, asphalt, tile, marble or stone [19]. In controlled conditions, gait termination, involving either feed-forward or feedback-based strategies on slippery surfaces, was similar in persons with PD and in healthy controls [20]. However, because of impaired postural instability, persons with PD may have difficulties in maintaining balance after slipping. Therefore, use of cane has been proposed to improve postural recovery from unexpected slips as a strategy to prevent falling [21].

Although tripping was not observed as a risk factor for outdoor falls, in our previous cross-sectional study, tripping was associated with outdoor falling [11]. In the population of older adults, tripping usually takes place outside and is caused by environment: uneven surfaces on the sidewalks and streets and when walking over curbs [19]. In terms of PD, some authors have highlighted that these individuals do not avoid obstacles adequately. For example, persons with PD exert less lifting force and take longer to complete tasks such as crossing over an obstacle [22]. Moreover, it appears that process of obstacle crossing in PD is influenced by lower extremity muscle strength, dynamic balance control and sensory integration ability of these individuals [23]. Specifically, dorsiflexor strength was identified as major determinant for crossing stride length and stride velocity. Another cause of outdoor tripping could be attributed to misjudgment of the level of foot elevation. In this way, persons with PD could easily trip not only when crossing over curbs, but when walking up the stairs. Because we found that tripping is independent risk factor for outdoor falling both in cross-sectional and in prospective cohort study, it would be beneficial to recommend persons with PD to elevate feet when crossing obstacles more than they perceive they should, to avoid tripping and, consequently, falling.

We observed that injuries were more common after outdoor falling, which is in line with our previous research [11]. Only contusions comprised consequences of indoor falls, while outdoor falls resulted in lacerations and fractures as well. Our results are similar to the ones reported by Rudzińska et al. [24], where 34 % of respondents described an injury, most commonly a contusion, as a result of falling. In the present prospective assessment of consequences of falls, fractures were the least common outcome. Similarly, fractures were more prevalent among outdoor fallers when we analyzed consequences of falls retrospectively [11]. This may be a result of sudden, unexpected landing on hard surfaces, whereas indoors a person is usually in a familiar setting and could potentially diminish an impact of falling by holding onto surrounding objects. Over the period of follow-up, two fractures involving hip and radius occurred in women. Hip fractures have been significantly more common in persons with PD compared with healthy controls [25]. In addition, being female has been associated with fall-induced fractures in PD, although female sex was not a predictor of injuries other than fractures [26]. Because of small proportion of fractures, we were not able to make an appropriate appraisal regarding sex differences.

With regards to limitations of this study, only those who denied falling in past 6 months were followed. However, we cannot exclude that due to recall bias, some patients did not report falls. We limited falls to those resulting in coming to rest inadvertently on the ground/floor, while additionally coming to rest at a lower lever other than the ground/floor is also considered as falling [27]. Not all circumstances preceding falls were mutually exclusive. It is recognized that falls often resulted from complex dynamic interactions of risk factors in these two groups. For example, the extrinsic factors can increase the risk of falls independently or, more importantly, by interacting with the intrinsic factors. Moreover, the risk of falling is higher when the environment requires greater postural control and mobility (i.e., when walking on a slippery surface). In that sense, it is reasonable to assess joint effect of all of these factors when exploring risk for falls in patients with PD. However, keeping in mind the fact that the fall-related information is self-reported, this type of methodological approach might be a source of information bias. However, to facilitate classification of causes for interpretation, we categorized tripping only as the extrinsic factor and limited it tripping over elements in environment, while falling due to “postural instability” referred to independent contribution of severity of PD (intrinsic factor). Because of small number of events in some categories of circumstances of falls (i.e. some circumstances of falls did not occur among single and other among recurrent falls) it is possible that the analysis lacked statistical power. In our study the age at onset and median PD duration was 4 years, which was below the expected. As a result, these finding might not be generalizable to a more elderly population with PD, at later stages of the disease and longer disease duration. Because persons with PD were able to walk and stand independently, we did not collect data on use of any kind of walking aid, such as cane or walker. Also, we did not take into account use of assistive devices or measures of balance which could have also influenced the study results. It is possible that other factors, which we did not include in our analysis, such as balance tests, measurement of gait speed or postural sway, might have introduced residual confounding.

In conclusion, the results of our study suggest that slipping is strongly associated with outdoor falls among persons with PD. Consequences of falling outdoors were more common compared to indoor falls. Similarly, a broader array of injuries was reported outdoors. These findings could be used to tailor fall prevention program with emphasis on balance recovery and negotiation of objects in environment.

References

Latt MD, Lord SR, Morris JG, Fung VS (2009) Clinical and physiological assessments for elucidating fall risk in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 24:1280–1289

Idjadi JA, Aharonoff GB, Su H, Richmond J, Egol KA, Zuckerman JD, Koval KJ (2005) Hip fracture outcomes in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 34(7):341–346

Allyson Jones C, Wayne Martin WR, Wieler M, King-Jesso P, Voaklander DC (2012) Incidence and mortality of Parkinson’s disease in older Canadians. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 18(4):327–331

Hely MA, Morris JG, Reid WG, Trafficante R (2005) Sydney multicenter study of Parkinson’s disease: non-L-dopa-responsive problems dominate at 15 years. Mov Disord 20:190–199

Parashos SA, Wielinski CL, Giladi N, Gurevich T (2013) Falls in Parkinson disease: analysis of a large cross-sectional cohort. J Parkinsons Dis 3(4):515–522

Grimbergen YAM, Munneke M, Bloem BR (2004) Falls in Parkinson’s disease. Curr Opin Neurol 17:405–415

Duncan RP, Leddy AL, Cavanaugh JT, Dibble LE, Ellis TD, Ford MP, Foreman KB, Earhart GM (2012) Accuracy of fall prediction in Parkinson disease: six-month and 12-month prospective analyses. Parkinsons Dis 2012:237673

Olanow CW, Watts RL, Koller WC (2001) An algorithm (decision tree) for the management of Parkinson’s disease: treatment guidelines (2001). Neurology 56(11 Suppl 5):S1–88

Bueno-Cavanillas A, Padilla-Ruiz F, Jiménez-Moleón JJ, Peinado-Alonso CA, Gálvez-Vargas R (2000) Risk factors in falls among the elderly according to extrinsic and intrinsic precipitating causes. Eur J Epidemiol 16(9):849–859

Lamont RM, Morris ME, Woollacott H, Brauer SG (2012) Community walking in people with Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsons Dis 2012:856237

Gazibara T, Pekmezovic T, Kisic Tepavcevic D, Tomic A, Stankovic I, Kostic VS, Svetel M (2014) Circumstances of falls and fall-related injuries among patients with parkinson’s disease in an outpatient setting. Geriatr Nurs 35(5):364–369

Hughes AJ, Daniel SE, Kliford I, Lees AJ (1992) Accuracy of clinical diagnosis of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease: a clinicopathological study of 100 cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr 55:181–184

Hoehn MM, Yahr MD (1967) Parkinsonism: onset, progression and mortality. Neurology 17:427–442

Goetz CG, Tilley BC, Shaftman SR et al (2008) Movement disorder society-sponsored revision of the unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale (MDS-UPDRS): scale presentation and clinimetric testing results. Mov Disord 23:2129–2170

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR (1975) Mini-mental state: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients with the clinician. J Psychiatr 12:189–198

Tomlinson CL, Stowe R, Patel S, Rick C, Gray R, Clarke CE (2010) Systematic review of levodopa dose equivalency reporting in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 25(15):2649–2653

Gazibara T, Pekmezovic T, Kisic Tepavcevic D, Tomic A, Stankovic I, Kostic VS, Pekmezovic T (2015) Fall frequency and risk factors in patients with Parkinson’s disease in Belgrade, Serbia: a cross-sectional study. Geriatr Gerontol Int 15(4):472–480

Morency P, Voyer C, Burrows S, Goudreau S (2012) Outdoor falls in an urban context: winter weather impacts and geographical variations. Can J Public Health 103(3):218–222

Li W, Keegan THM, Sternfeld B, Sidney S, Quesenberry CP Jr, Kelsey JL (2006) Outdoor falls among middle-aged and older adults: a neglected public health problem. Am J Public Health 96:1192–1200

Oates AR, Van Ooteghem K, Frank JS, Patla AE, Horak FB (2013) Adaptation of gait termination on a slippery surface in Parkinson’s disease. Gait Posture 37(4):516–520

Boonsinsukh R, Saengsirisuwan V, Carlson-Kuhta P, Horak FB (2012) A cane improves postural recovery from an unpracticed slip during walking in people with Parkinson disease. Phys Ther 92(9):1117–1129

Nocera JR, Horvat M, Ray CT (2010) Impaired step up/over in persons with Parkinson’s disease. Adapt Phys Activ Q 27(2):87–95

Liao YY, Yang YR, Wu YR, Wang RY (2014) Factors influencing obstacle crossing performance in patients with Parkinson’s disease. PLoS One 9(1):e84245

Rudzińska M, Bukowczan S, Banaszkiewicz K, Stozek J, Zajdel K, Szczudlik A (2008) Causes and risk factors of falls in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Neurol Neurochir Pol 42(3):216–222

Walker RW, Chaplin A, Hancock RL, Rutherford R, Gray WK (2013) Hip fractures in people with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease: incidence and outcomes. Mov Disord 28(3):334–340

Wielinski CL, Erickson-Davis C, Wichmann R, Walde-Douglas M, Parashos SA (2005) Falls and injuries resulting from falls among patients with Parkinson’s disease and other parkinsonian syndromes. Mov Disord 20:410–415

World Health Organization. Fact sheet 344: falls. October 2012. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs344/en/index.html. Accessed 31 Oct 2012

Acknowledgments

This investigation was supported by the Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Serbia (Grants No 175087 and 175090).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gazibara, T., Kisic-Tepavcevic, D., Svetel, M. et al. Indoor and outdoor falls in persons with Parkinson’s disease after 1 year follow-up study: differences and consequences. Neurol Sci 37, 597–602 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-016-2504-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-016-2504-2