Abstract

We aimed to determine the prevalence and risk factors of restless legs syndrome in Edirne and its districts, located in Western Thrace, which is the most western part of Turkey. In this study, 4003 individuals who could communicate and agreed to participate in the study were evaluated. To obtain the data from the applicants in 30 Family Health Centres in Edirne and its districts, a face-to-face questionnaire that consisted of 54 questions was prepared by the researchers. The questionnaire included general information, questions to evaluate potential concomitant comorbid conditions and questions regarding the symptomatology used in restless legs syndrome (RLS) diagnosis, as well as questions to evaluate insomnia and tension-type headache secondary to insomnia according to the ICD-II Criteria (International Classification of Sleep Disorders-II Criteria). Of 4003 individuals, 282 were diagnosed with RLS according to the questionnaire results from Edirne and its districts, and the prevalence of RLS was 7 %. Approximately, 47.9 % of the patients with RLS were male, and 52.1 % were female, which was not significantly different (p > 0.05). Anaemia was identified in 41.1 % of the cases and control group was detected in 19.4 %, which was significantly different (p < 0.001). Secondary insomnia was identified in 64.2 % of the cases with RLS and was not detected in 35.8 %, which was significantly different (p < 0.001). RLS prevalence studies will increase the awareness of the community and provide early diagnosis and treatment, as well as serve as a basis to reduce morbidity and improve the quality of life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Restless legs syndrome (RLS) is a movement disorder characterised by an urge to move the legs, typically during rest, and is predominately accompanied by unpleasant leg sensations. During sleep, most patients experience periodic leg movements in their small extensor muscles of the lower extremities or feet for 15–30 min. This syndrome has been increasingly studied in previous years. It is a common cause of insomnia [1–4]. In the epidemiological studies conducted worldwide for RLS, a broad range of prevalence rates have been reported from 0.01 to 24 %, and these findings were affected by the methodological approach and differences in the administration of questionnaires [4, 5].

RLS has negative impacts on the quality of life in patients. This condition is the subject of an increasing number of epidemiological studies [6, 7]. Therefore, it is extremely important to determine the prevalence of RLS, which is common but less known, as well as to determine the quality of life and other concomitant chronic processes.

The main aim of this population-based study is to determine the epidemiological features and prevalence of patients diagnosed with RLS who received treatment or who remained undiagnosed and did not receive treatment. Additionally, we aim to increase awareness of the disorder among primary care physicians so that RLS, which causes considerable social disability and loss of productivity in the workforce, will be better treated. Population-based prevalence studies regarding the prevalence of RLS in Turkey are extremely limited [8–11], and it is extremely important to perform studies to compare different regions and different socioeconomic areas. Therefore, in this study, which was conducted in Edirne and its districts, we aimed to determine the potential RLS prevalence in Turkey. Edirne is the most western part of Turkey and has the highest longitude/latitude rate with 40°–41° longitude and 26°–27° latitude. Individuals in this region are primarily Caucasian.

RLS is a debilitating disease that affects an individual’s daily life, mood and functionality and commonly goes unrecognised by physicians and society. This disorder disrupts mental health and quality of life, which also leads to an economic burden [12]. We aimed to determine the prevalence of RLS among people aged 18 or older who live in Edirne and its districts.

Methods

Study populations

To assess the prevalence of RLS in Edirne and its districts, 4003 volunteers, including 2033 men and 1970 women, were included in the study. The study was approved by the Trakya University Medical Faculty Ethics Committee on January 16, 2013 (approval number 2013/12). The study population comprised individuals aged 18 or older who live in Edirne and its districts. In 2012, the adult population in this region was 314,975, including 128,667 in Edirne, and 186,308 in the surrounding districts. The population consists of 51.0 % men and 49.0 % women. Taking for reference a 5 % prevalence of RLS to identify significant differences at 1 %, 3932 individuals were considered necessary for inclusion in the study based on a 5 % error rate and 80 % overall power.

To account for the possibility of missing cases of RLS in our study population, we added an additional 10 % to the estimated number of individuals needed, for a total of 4369. However, ultimately, only 4003 individuals were included. The sample selection was based on the World Health Organization’s (WHO) 30-cluster sampling method [13]. Family Health Centres (FHCs) were designated as the cluster unit. To select clusters for study primarily from the Edirne Health Directorate province, the populations of all FHCs in all rural areas of the province and at the region’s geographical boundaries (neighbourhoods, streets, and in the countryside) were sampled. FHCs represented a sample of the population after a total of 30 clusters were selected by a simple random sampling method. To collect study information, the total populations of 50 FHCs in Edirne and its districts were chosen; 30 clustered with a simple random sampling method (12 FHCs in Edirne; 18 FHCs in its districts). The sample size was established by weighting the populations served by family physicians by both age and gender. On average, from 41 to 259 individuals belonged to each cluster. A total of 4003 individuals were included.

Neurology and epidemiology specialists prepared a survey including 54 questions, and randomly selected participants were asked to complete it in person. Each individual who agreed to participate in the study was evaluated in an FHC. FHC physicians and participants were informed in detail of the importance of the diagnosis and treatment of RLS and insomnia. Only expert physicians can specify diagnosis of the diseases under study. Once participants understood the value of this study for the health of the individual and community, they voluntarily agreed to participate. The questionnaire solicited demographic information, including age, gender, profession, alcohol use and smoking status of the participants, as well as a family history of RLS, earlier diagnosis of RLS, presence of anaemia (haemoglobin values <13.5 mg/dl in males and <12 mg/dl in females), and treatment for anaemia, diabetes mellitus (DM), rheumatic diseases, kidney diseases, lumbar hernia, varices, or hypertension (systolic blood pressure: 140–159 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure: 90–99 mmHg). In addition to the standard RLS diagnostic criteria, the sensation of being pushed and pulled, restlessness, lurching, tension, contraction, itching, burning, prickling, electrification, tingling, numbness, unidentified discomfort and time of symptom onset were investigated. In the final part of the questionnaire, insomnia was examined. Difficulties in falling asleep and maintaining sleep, waking up extremely early, non-restful sleep, low-quality sleep, daytime sleepiness, attention and concentration difficulties, difficulties in social life, daytime nervousness, daytime decreased motivation and energy loss, and a tendency towards accidents were examined in patients reporting insomnia. In the final part of the questionnaire, bilateral and non-throbbing tension-type headaches without vomiting, photophobia, or phonophobia were examined. To evaluate the utility of the questionnaire, a pilot study on 50 individuals was conducted. Incomprehensible questions or problems encountered in its implementation were addressed, and the intelligibility of the questionnaire was determined. In 1995, the RLS diagnostic criteria were determined by an international RLS study group, and in 2003, these criteria were revised [14, 15]. A definitive diagnosis of the disease is only possible if four symptoms are present in the same individual. As previously discussed, in addition to these diagnostic criteria, this questionnaire included general information and questions regarding concomitant comorbid conditions, such as insomnia and headache. An insomnia diagnosis in the patients was determined by the International Classification of Sleep Disorders-II (ICSD-II) criteria [16], and the existence of tension-type headaches was determined by the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-II) criteria [17]. The inclusion criteria of the volunteers were as follows: capable of communication, motivated to participate and cooperative in answering questions. Individuals who had psychiatric diseases or who had undergone surgery on a lower extremity were excluded. Questionnaires were administered by a neurologist who was also the principal investigator of the study. All questionnaires and all patients suspected of having RLS were evaluated individually by the same principal investigator.

Statistical analysis

Statistical evaluation was performed using SPSS 21 statistics software. A one-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to assess the eligibility for normal distribution of the measured data because the data did not exhibit a normal distribution, a Mann–Whitney U test was used for comparison between the groups. A Pearson’s χ 2 test, Fisher’s exact χ 2 analysis and Kolmogorov–Smirnov two-sample test were used for qualitative data. The mean values ± standard deviations were determined as descriptive statistics. Stepwise Logistic regression analyses were applied. A significance limit was set as p < 0.05 for all statistics.

Assessment of RLS

RLS is diagnosed by the presence of specific symptoms, and the diagnostic criteria have been established by the International Restless Legs Study Group (IRLSSG) [18]. We implemented standardised questions in both cohorts that address the four minimal diagnostic criteria of the IRLSSG. The participants were asked: “Four cardinal signs of RLS were: (1) an urge, often defined as discomfort, to move the feet, (2) motor uneasiness (an urge to move the legs or massage them to relieve the pain), (3) temporary relief with activity, worsening of symptoms by relaxation, and (4) worsening of symptoms at the end of the day or at night [14, 15]. The participants who answered yes to all four questions were diagnosed with RLS.

Results

The study population consisted of 4003 participants, including 50.8 % men (n = 2033) and 49.2 % women (n = 1970). The RLS prevalence was 7 %, and 282 participants were evaluated as RLS positive. One hundred thirty-five (47.9 %) of the RLS patients were men, and 147 (52.1 %) were women. The mean age of the patients diagnosed with RLS was 48.6 ± 14.7, and the other individuals had a mean age of 48.2 ± 15.04. There was a non-significant difference in the prevalence of RLS between women and men (p = 0.314). There was a significant difference in the mean age of clinic patients with and without RLS (p = 0.032).

There was a significant difference in working status between the RLS positive and negative participants; the proportion of RLS-positive participants with jobs was higher (p = 0.013). There was also a significant difference in the occupational groups between the RLS positive and negative participants (p = 0.001). The frequency of RLS was significantly increased in health care workers. One hundred forty-one (50 %) of the RLS-positive participants were non-smokers, whereas 54 (19.1 %) had quit smoking and 87 (30.9 %) were still smoking; this difference was not significant (p = 0.905). Two hundred twenty-six (80.4 %) of the RLS-positive participants did not drink alcohol, whereas 17 (6 %) had quit drinking and 38 (13.5 %) drank alcohol; this difference was not significant (p = 0.088). Family history was negative in 83.7 % of the cases and positive in 16.3 %, which was significantly different (p = 0.001). Moreover, during our study, only 25.2 % of RLS-positive participants had a previous RLS diagnosis, whereas 74.8 % of RLS-positive participants were newly diagnosed, a difference that was statistically significant (p = 0.001). Anaemia was identified in 41.1 % of the cases and control group was detected in 19.4 %, which was significantly different (p < 0.001). The basic diagnostic criteria used in the diagnosis of RLS and the statistical analysis results in terms of clinical characteristics are summarised in Table 1.

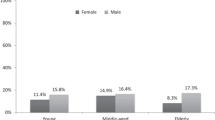

In terms of age and gender, the distribution of the prevalence of RLS among women and among the total population was not significantly different between age groups (p = 0.796 and p = 0.792, respectively; Fig. 1). The prevalence of RLS over the administrative divisions of the province of Edirne is provided in Table 2. There was no significant difference between the prevalence of RLS between administrative divisions (p = 0.574).

Patients with RLS and insomnia were evaluated as RLS-related having secondary insomnia. Secondary insomnia was identified in 64.2 % of the RLS cases and was absent in 35.8 % of the cases. There was a significant difference in the existence of secondary insomnia between the RLS positive and negative patients (p = 0.001). The basic components of sleep, potential social integration problems due to insomnia, fatigue, tendency to have accidents, and the occurrence of headaches were evaluated and are summarised in Table 3. In 138 (48.9 %) of the RLS positive cases, tension-type headaches were identified. Thus, RLS and secondary insomnia have negative effects on the quality of life and lead to a loss of workforce productivity, as demonstrated by the identification of secondary complications. There was a significant difference in the prevalence of diabetes mellitus (DM), lumbar hernia, varices and hypertension between RLS positive and negative participants, and RLS negative cases had a higher frequency of these diseases Table 4.

When patients were questioned regarding the duration of RLS symptoms, it was noted that the onset of their complaints was 1 month before for 3 (1.1 %) individuals, 3 months before for 5 (1.8 %) individuals, 6 months before for 6 (2.1 %) individuals, 1 before for 35 (12.4 %) individuals and longer than 1 year for 209 (74.1 %) individuals, and the differences were significant (p < 0.001).

Discussion

Although RLS is a neurological disorder that affects a substantial portion of the general population, there are millions of individuals who complain of RLS but who have not been formally diagnosed or treated [4]. The pathophysiology and epidemiology of this disease are uncertain. It is thought that the disease has a multifactorial etiology. Most hypotheses have focused on dopaminergic mechanisms, iron deficiency, and genetics. Dopaminergic mechanisms are thought to play a central role. In addition, iron deficiency and genetic hypotheses have been strongly emphasised. In our study, we identified RLS cases generally that developed secondary to genetic criteria and iron deficiency.

Our study is the first large-scale population-based RLS prevalence study conducted on a Turkish population with a large sample size (4003) sampled from the city centre and all districts. Other RLS prevalence studies conducted in Turkey are limited to a province or district. Other Turkish studies detected a prevalence of RLS between 3 and 9 %. In accordance with the changing boundaries of Edirne province and district, the prevalence of RLS in rural areas was determined as 7 %. When other studies conducted in Turkey regarding the prevalence of RLS were examined, the reported values varied. The RLS prevalence in the northern part of Turkey, in Kandıra, was 3.2 % [11]. In a study conducted in the southern part of Turkey, in Mersin, 3234 patients were screened, and the prevalence of RLS was 3.19 % [8]. In a study with 815 patients conducted in Ankara, in Central Anatolia, the RLS prevalence was 5.52 % [9]. In another study conducted in Orhangazi, Bursa, which is located in the south of the Marmara Region, 1256 individuals were screened, and the prevalence of RLS was 9.71 % [10]. Studies conducted in Turkey have generally included door-to-door interviews using a short questionnaire to identify possible cases of RLS, after which physicians diagnosed the suspected cases. However, Sevim et al. applied multistep, stratified, cluster, and systematic samplings. Compared with the other prevalence studies conducted in different regions of Turkey, our study utilised sample selection methods based on the WHO 30-cluster sampling method. Surveys were filled out in person by individuals who were invited to FHCs in order to prevent missing data. Additionally, our study differs from other Turkish RLS prevalence studies because insomnia and other comorbid conditions were investigated.

Previous studies have reported that the majority of RLS patients developed insomnia secondary to RLS and experienced, on the following day, symptoms that affected their job performance, such as fatigue and a tendency towards accidents stemming from insomnia [15, 19, 20]. In our study, the frequency of insomnia developed secondary to RLS was 64.2 %, which was significant. In a study by Kushida et al. [21], 1254 individuals with sleeping disorders were screened, and the prevalence of RLS was 29.3 %. In our study, secondary insomnia was identified in patients with RLS, which is also consistent with the literature. Therefore, RLS might cause indirectly a deterioration in quality of life and it might create problems with social communication caused by secondary insomnia. Additionally, 8.8 % of the RLS negative participants had insomnia, mainly due to psychological factors. RLS might affect sleep quality, quality of life and cognitive activities at a relatively high prevalence, but quality of life is reasonably improved after treatment. However, a full appreciation of its severity and its impact on daily life remains unclear.

In our study, we found that patients who have just been diagnosed represented 25 % of the patients. However, the symptoms of RLS were ongoing in 74.1 % of patients, most likely since the condition was not evaluated by a specialist who could diagnose RLS as it is not well recognised by the public. Furthermore, considering the experience of newly diagnosed RLS patients, these findings indicate the necessity of early diagnosis and treatment of RLS, which causes insomnia, anxiety disorders, and a deceleration in cognitive functions, as well as a considerable deterioration in the quality of life.

In the literature, the incidence and prevalence of RLS gradually increases until a certain age and then subsequently decreases [22, 23]. It is widely recognised that the peak of the disease occurs between the ages of 35–44 and 45–54 [19, 24]. Our findings are similar to those in the literature, and we determined that the cases of patients aged 35–44 and 45–54 years were the most common. There was no significant difference between the age groups among men and women.

In the literature, anaemia was detected to be the most common secondary cause of RLS. Especially after women’s pregnancy, the tendency of iron deficiency increases, and the reason why middle-aged or older women had statistically significant higher rates are associated with the detection of this condition [11]. Our findings are similar to those data in the literature. In our study, we determined that the RLS cases anaemia rate higher. Although in some studies the anaemia rate in patients with RLS was detected high [11], other studies showed no higher rate of anaemia [25].

Some studies do not report an increased risk for RLS in patients with DM [25–28], whereas other studies do report an increased risk [11, 29]. In our study, the RLS frequency in the patients with DM was low. In the literature, hypertension, cardiovascular diseases and cerebrovascular diseases have been associated with RLS [30]. In our study, 134 (47.5 %) of 282 RLS patients exhibited hypertension; however, this number was not high enough to be significant. An evaluation of these diseases might be important, as they might be associated with RLS.

In the literature, the frequency of association of migraine headaches with RLS ranges from 7 to 14 % [31]. Gupta et al. [32] reported the rate of migraine-type headaches in 99 RLS diagnosed patients as 22.8 %. In one study, the association rate of tension-type headaches in 265 RLS patients was 24.9 % [33]. In our study, 138 (48.9 %) of the RLS patients were detected to have tension-type headaches according to the ICHD-II headache classification.

One of the limitations of our study is that the severity of RLS was not assessed. The aim of the study was to determine the prevalence of RLS and its secondary complications, such as insomnia, and our questionnaire consisted of 54 questions. Consequently, in addition to the broad nature of our study, we examined the severity of RLS using 54 questions supplied by the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group (IRLSSG) in our pilot study; however, the data could not be collected because of the impatience of the participants. This issue represents one of the study’s weaknesses. Another limitation of our study is that although a pilot study was performed to test the feasibility of the study, a validation of the RLS diagnosis was not performed. One of the strengths of our study is the extent of the epidemiological study, which contains the Edirne provincial centre and all of its districts. Edirne is located in a region that has not experienced a massive population displacement or migration. We believe that the best way to determine the contribution of racial and genetic characteristics to developing RLS is to conduct comprehensive studies in these regions. Another strength of our study was the detailed assessment of insomnia secondary to RLS, which is commonly present but less studied. As specified in the quality-of-life scales regarding RLS [34], the presence of insomnia among patients with RLS has been reported to be the main reason for the loss of workforce productivity and the high costs to society, which lead to impairments in quality of life. Another strength of our study is that questionnaires were administered in our FHCs by family physicians that were informed regarding RLS and insomnia. Thus, we believe that in Edirne and its districts, physician and public awareness of RLS has greatly increased.

As a result, in many countries and regions, despite many efforts and studies regarding the prevalence, epidemiology, mechanisms and treatment of the disease, RLS has not been sufficiently elucidated. Thus, for the determination of the prevalence and mechanisms of the disease, additional detailed and comprehensive studies are needed.

References

Allen RP, Picchietti D, Hening WA, Trenkwalder C, Walters AS, Montplaisi J (2003) Restless legs syndrome: diagnosticcriteria, special considerations, and epidemiology. A report from the restlesslegs syndrome diagnosis and epidemiology workshop at the National Institutesof Health. Sleep Med 4:101–119

Salas RE, Rasquinha R, Gamaldo CE (2010) All the wrong moves: a clinical review of restless legs syndrome, periodic limb movements of sleep and wake, and periodic limb movement disorder. Clin Chest Med 3:383–395

Ekbom K, Ulfberg J (2009) Restless legs syndrome. J Intern Med 266:419–431

Innes KE, Selfe TK, Agarwal P (2011) Prevalence of restless legs syndrome in North American and Western European populations: a systematic review. Sleep Med 12:623–634

Ohayon MM, O’Hara R, Vitiello MV (2012) Epidemiology of restless legs syndrome: a synthesis of the literature. Sleep Med Rev 16:283–295

Lee HB, Cho YW, O’Hara R (2012) Validity of RLS diagnosis in epidemiologic research: time to move on. Sleep Med 13:325–326

Högl B (2011) A new generation of studies in RLS epidemiology. Sleep Med 12:813–814

Sevim S, Dogu O, Camdeviren H, Bugdayci R, Sasmaz T, Kaleagasi H, Aral M, Helvaci I (2003) Unexpectedly low prevalence and unusual characteristics of RLS in Mersin, Turkey. Neurology 61:1562–1569

Yilmaz NH, Akbostanci MC, Oto A, Aykac O (2013) Prevalence of restless legs syndrome in Ankara, Turkey: an analysis of diagnostic criteria and awareness. Acta Neurol Belg 113:247–251

Erer S, Karli N, Zarifoglu M, Ozcakir A, Yildiz D (2009) The prevelance and clinical features of restless legs syndrome: a door to door population study in Orhangazi, Bursa in Turkey. Neurol India 57:729–733

Taşdemir M, Erdoğan H, Börü UT, Dilaver E, Kumaş A (2010) Epidemiology of restless legs syndrome in Turkish adults on the western Black Sea coast of Turkey: a door-to-door study in a rural area. Sleep Med 11:82–86

Allen RP, Bharmal M, Calloway M (2011) Prevalence and disease burden of primary restless legs syndrome: results of a general population survey in the United States. Mov Disord 26:114–120

Singh J, Jain DC, Sharma RS, Verghese T (1996) Evaluation of immunization coverage by lot quality assurance sampling compared with 30-cluster sampling in a primary health centre in India. Bull World Health Organ 74:269–274

Ondo WG (2005) Restless legs syndrome. Neurol Clin 23:1165–1185

Hening W, Walters AS, Allen RP (2004) Impact, diagnosis and treatment of restless legs syndrome (RLS) in a primary care population: the REST (RLS epidemiology, symptoms, and treatment) primary care study. Sleep Med 5:237–246

Dohnt H, Gradisar M, Short MA (2012) Insomnia and its symptoms in adolescents: comparing DSM-IV and ICSD-II diagnostic criteria. J Clin Sleep Med 15:295–299

(2004) The International Headache Classification (ICHD-2) 2nd edn. http://ihs-classification.org/en/. Accessed 15 Jan 2013

Walters AS, LeBrocq C, Dhar A, Hening W, Rosen R, Allen RP, Trenkwalder C, International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group (2003) Validation of the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group rating scale for restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med 4:121–132

Allen RP, Walters AS, Montplaisir J, Hening W, Myers A, Bell TJ, Ferini-Strambi L (2005) Restless legs syndrome prevalance and impact; REST General population study. Arc Intern Med 165:1286–1292

Garcia-Borreguero D (2006) Time to REST; epidemiology and burden. Eur J Neurol 13:15–20

Kushida CA, Nichols DA, Simon RD, Young T, Grauke JH, Britzmann JB, Hyde PR, Dement WC (2000) Symptom-based prevalence of sleep disorders in an adult primary care population. Sleep Breath 4:9–14

Van De Vijer DA, Walley T, Petri H (2004) Epidemiology of restless legs syndrome as diagnosed in UK primary care. Sleep Med 5:435–440

Tison F, Crochard A, Léger D, Bouée S, Lainey E, El Hasnaoui A (2005) Epidemiology of restless legs syndrome in French adults: a nationwide survey: the INSTANT Study. Neurology 65:239–246

Rijsman R, Neven AK, Graffelman W, Kemp B, de Weerd A (2004) Epidemiology of restless legs in the Netherlands. Eur J Neurol 11:607–611

Kim KW, Yoon IY, Chung S, Shin YK, Lee SB, Choi EA, Park JH, Kim JM (2010) Prevalence, comorbidities and risk factors of restless legs syndrome in the Korean elderly population—results from the Korean Longitudinal Study on Health and Aging. J Sleep Res 19:87–92

Hadjigeorgiou GM, Stefanidis I, Dardiotis E, Aggellakis K, Sakkas GK, Xiromerisiou G, Konitsiotis S, Paterakis K, Poultsidi A, Tsimourtou V, Ralli S, Gourgoulianis K, Zintzaras E (2007) Low RLS prevalence and awareness in central Greece: an epidemiological survey. Eur J Neurol 14:1275–1280

Winter AC, Berger K, Glynn RJ, Buring JE, Gaziano JM, Schürks M, Kurth T (2013) Vascular risk factors, cardiovascular disease, and restleş legs syndrome in men. Am J Med 126:228–235

Froese CL, Butt A, Mulgrew A, Cheema R, Speirs MA, Gosnell C, Fleming J, Fleetham J, Ryan CF, Ayas NT (2008) Depression and sleep-related symptoms in an adult, indigenous, North American population. J Clin Sleep Med 4:356–361

Celle S, Roche F, Kerleroux J, Thomas-Anterion C, Laurent B, Rouch I, Pichot V, Barthélémy JC, Sforza E (2010) Prevalence and clinical correlates of restless legs syndrome in an elderly French population: the synapse study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 65:167–173

Ferini-Strambi L, Walters AS, Sica D (2013) The relationship among restless legs syndrome (Willis-Ekbom Disease), hypertansion, cardiovascular disease, and cerebrovascular disease. J Neurol 21:1432–1459

Smitherman TA, Burch R, Sheikh H, Loder E (2013) The prevalence, impact, and treatment of migraine and severe headaches in the United States: a review of statistics from national surveillance studies. Headache 53:427–436

Gupta R, Lahan V, Goel D (2012) Primary headaches in restless legs syndrome patients. Ann Indian Acad Neurol 15:104–108

Gozubatik-Celik G, Benbir G, Tan F, Karadeniz D, Goksan B (2014) The prevalence of migraine in restless legs syndrome. Headache 54:872–877

Abetz L, Arbuckle R, Allen RP, Mavraki E, Kirsch J (2005) The reliability, validity and responsiveness of the Restless Legs Syndrome Quality of Life questionnaire (RLSQoL) in a trial population. Health Qual Life Outcomes 3:79

Conflict of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Güler, S., Caylan, A., Nesrin Turan, F. et al. The prevalence of restless legs syndrome in Edirne and its districts concomitant comorbid conditions and secondary complications . Neurol Sci 36, 1805–1812 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-015-2254-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-015-2254-6