Abstract

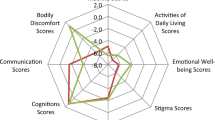

The affect of gender differences on clinical presentation of Parkinson’s disease (PD) remains controversial. De novo PD subjects were recruited from a trial-based multicenter cohort in clinical sites of Chinese Parkinson Study Group. Demographic information, motor and non-motor symptom measurements were performed by face-to-face interview using specific scales. Scores and frequencies of symptoms were compared between male and female patients, and regression models were used to control the effects of age and disease duration. Totally 428 PD patients were enrolled in this study, and 60.3 % of them were male. Total UPDRS scores were not significantly different between male and female (25.02 ± 12.84 vs. 25.24 ± 13.22, adjusted p = 0.984). No significant gender differences were found on scores for four cardinal motor signs, neither on motor subtypes (PIGD 19.0 vs. 15.9 %, adjusted p = 0.303). Female patients more likely had depressive symptoms (38.8 vs. 27.5 %, adjusted p = 0.023; CES-D score 13.78 ± 10.91 vs. 11.23 ± 9.42, adjusted p = 0.015). Male patients had significantly higher scores for MMSE (28.26 ± 2.21 vs. 27.00 ± 3.38, adjusted p = 0.0001), and lower scores for identification (1.39 ± 1.63 vs. 2.01 ± 2.63, adjusted p = 0.002) in ADAS-cog. No significant differences were found for other non-motor symptoms including motivation problems (male 29.8 % vs. female 30.6 %, adjusted p = 0.760), fatigue (62.6 vs. 70.5 %, adjusted p = 0.140), constipation (37.2 vs. 30.1 %, adjusted p = 0.243), and sleep quality (57.6 vs. 61.3 %, adjusted p = 0.357; PSQI score: 5.62 ± 3.31 vs. 6.10 ± 3.53, adjusted p = 0.133). Female might be more depressed and have worse performance on cognition in early untreated PD patients, but gender differences are not apparent on motor and other non-motor symptoms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a chronic neurodegenerative disease diagnosed mainly based on clinical features. Increasing evidence suggests that PD has phenotypic heterogeneity in both motor and non-motor symptoms [1, 2]. As indicated by epidemiological studies, men are more prevalent in PD [3–5]. There are limited studies on gender differences on clinical manifestations, and findings remain controversial. Women seem to present later age at onset, tremor-predominant, higher instability scores from Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS), more positive history of depression, worse capacity of activities of daily living (ADL) and more severity with levodopa-induced dyskinesia in several studies [6–12], while male gender are likely to predict worse rigidity score, and higher risk for rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behavior disorder, dementia and death [7, 13–15]. But other studies failed to find consistent results [9, 11]. When deep brain stimulation (DBS) therapy is concerned, female patients seem to experience greater benefits in ADL and showed a positive effect on mobility and cognition [9, 10].

Recently, several studies used non-motor symptoms scale (NMSS) to investigate the gender differences on non-motor symptoms (NMS). Martinez-Martin and colleagues [16] evaluated the prevalence and severity of NMS by gender using NMSS in an international population, and found that fatigue, nervousness, sadness, constipation, restless legs, and pain were predominantly affected in women, and daytime sleepiness, dribbling saliva, interest in sex, and sexual dysfunction in men, which was confirmed by Solla et al. [17] later in Sardinian patients. Sardinian outpatients were enrolled from a single site, and NMSS, the Montreal Cognitive assessment (MoCA) and the Frontal Assessment Battery (FAB) were performed supplied with diagnosis of depression, anxiety disorders, delusions and hallucinations. This study confirmed that women were more likely to report problems of sleep/fatigue, and mood, while the sexual dysfunction domain was reported with a significantly higher score in male patients. Moreover, women were more likely than men to present with tremor as initial symptom and worse UPDRS instability score.

However, Picillo and colleagues [18] could not replicate some of these findings in early, drug naïve PD patients. They assessed gender effect on the prevalence of NMS in a large cohort of early, drug-naïve PD patients, and found male PD patients did report more problems with sex related and taste/smelling difficulties than female PD patients, but female patients did not present higher prevalence of mood symptoms as compared to male PD patients.

Since most of the anti-Parkinson medications affect the motor symptoms, and some even affect NMS, such as levodopa could cause nausea and somnolence, while Artan may be related to psychiatric symptoms, it is important to evaluate the gender characteristics in a natural history of PD. Furthermore, rare data on gender differences are available in Chinese. Here, we reported a cross-sectional study to investigate gender differences on motor and non-motor symptoms in de novo early Chinese PD patients, to better understand PD gender specific manifestations.

Methods

Subjects

Subjects were recruited from a trial-based multicenter cohort established in 2005–2006 among sites of the Chinese Parkinson Study Group. PD patients were diagnosed according to UK Brain Bank criteria by movement disorder specialists [5]. Only de novo PD patients were enrolled in the trial and no dopaminergic treatments were given before and during the trial period. Patients with onset age ≥30 years, Hoehn and Yahr (H&Y) stage ≤3, no apparent cognitive problems and capable to complete all measurements (Mini-Mental Status Examination, MMSE ≥24) were enrolled in this study. Demographic information and clinical characteristics were collected by face-to-face interviews.

Motor measurement

Motor symptoms of PD were evaluated by UPDRS. Scores for tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia and instability were abstracted and calculated from UPDRS III as previously reported [17]. Motor subtypes were defined as tremor dominant (TD), postural instability/gait difficulty (PIGD) and intermediate type as described by Jankovic et al. [19].

Non-motor measurements

Non-motor symptoms of PD were evaluated using specific questionnaires. Full-length, 20-item version of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scales (CES-D) was used for depression evaluation and a total score ≥16 was defined as depressive status [20]. The quality of sleep was assessed by Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) and a total score ≤5 was considered to be good sleep quality. MMSE was used for cognition screening. Subscales of memory, orientation, and identification in the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive (ADAS-Cog) were used for further evaluation of cognitive status. Constipation was measured by asking if they suffered from constipation (bowel action less than three times weekly). Fatigue was determined by a single question “Do you have feeling of fatigue?” The fourth question in UPDRS part I (0 = normal; 1 = less assertive than usual; more passive; 2 = loss of initiative or disinterest in elective (nonroutine) activities; 3 = loss of initiative or disinterest in day to day (routine) activities; 4 = withdrawn, complete loss of motivation.) was considered to be evaluation for motivation, and scores >0 were considered to have motivation problem. Question for sensory complaints related to parkinsonism in UPDRS part II (0 = none; 1 = occasionally has numbness, tingling, or mild aching; 2 = frequently has numbness, tingling, or aching; not distressing; 3 = frequent painful sensations; 4 = excruciating pain.) was used to assess sensory complaints in patients, and scores >0 were considered to have sensory problem.

Ethics

Study protocol was approved by Ethics Committee of Xuanwu Hospital of Capital Medical University, and informed consent was signed by each participant.

Statistics

SPSS19.0 was used for database and analyses. The Chi-square test was performed to analyze the differences in discrete data, and t test was used for continuous data. Logistic regression model and linear model were used to control the effects of age and disease duration. p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Demographics of participants

Totally 428 PD patients were enrolled in this study, with mean age at 60.62 ± 10.77 years and 60.3 % of them were male. Men had a shorter disease duration as compared with female patients (1.75 ± 1.30 vs. 2.16 ± 2.35, p = 0.030), while age, age at onset and H&Y stage did not differ significantly between male and female subjects (Table 1).

Gender differences on motor symptoms

As shown in Table 2, UPDRS total score was 25.11 ± 12.98 in the whole population, and appeared to be similar between male and female group, so as scores for Part I, Part II, and Part III. Furthermore, no significant differences were found on scores for four cardinal motor symptoms, neither on motor subtypes.

Gender differences on non-motor symptoms

Non-motor symptoms were frequent in PD patients. The frequencies of patients who had motivation/initiative problems, or depression, or sensory complaints or constipation exceeded 30 %, and nearly 60 % patients had fatigue or bad sleep quality. Female patients seemed to be more likely depressed, since the female group had higher scores of CES-D (13.78 ± 10.91 vs. 11.23 ± 9.42, adjusted p = 0.015), and higher frequency of depression (38.8 vs. 27.5 %, adjusted p = 0.023) as compared to male (Table 3). Male patients had less complaint of sensory problems (34.1 vs. 44.1 %), but it was not statistically significant after adjusted for age and disease duration (adjusted p = 0.065). Men had significantly higher scores for MMSE (28.26 ± 2.21 vs. 27.00 ± 3.38, adjusted p = 0.0001), and when ADAS-Cog was used for cognition evaluation, only scores for identification was statistically different between the two groups, with higher scores in female (2.01 ± 2.63 vs. 1.39 ± 1.63, adjusted p = 0.002). No significant differences between male and female groups were found for other NMS including motivation problems, fatigue, constipation, and sleep quality.

Discussion

The current study used UPDRS and specific scales for NMS to investigate the motor and non-motor symptoms in de novo early PD patients, and found that female presented higher frequency and more severity of depression and worse performance on cognition compared with male, but there was no significant gender difference on motor symptoms.

Gender differences on clinical manifestations have been mainly analyzed in treated PD patients [21], and found relatively benign phenotype, more bradykinesia and mood problems in female, and more sex related problems in male. Consistent with previous reports, depression was more prevalent in our female patients. This phenomenon is also common in general elderly population with more frequent depression in female than male, which might be explained by biological factors. A recent longitudinal study reported prospective assessment of gender-related differences of NMS before and after starting dopaminergic therapy [22], and found that sadness/blues showed a significant percent reduction at follow-up both in men and women, which suggested limited impact of drug treatment on gender difference. However, this finding was conflict to the results reported recently by Picillo and colleagues [18] who found female patients presented similar prevalence of mood symptoms as compared to male in drug-naïve PD patients. Different assessments might attribute to the different findings. Non-Motor Symptoms Questionnaire (NMSQ) used by Picillo et al. is a screening tool for NMS in PD patients designed to draw attention to the presence of NMS. While the 20 items in CES-D scale measure symptoms of depression in nine different domains as defined by the American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (fourth edition), and could detect depressive status more comprehensively and accurately.

Cognitive differences between male and female PD remains unexamined and controversial. The study carried by Lyons and colleagues [11] indicated slightly higher MMSE scores for women relative to men in total 630 PD patients, while Picillo et al. [18] did not replicate this finding in drug-naïve patients with a single question of memory. Riedel and colleagues [23] investigated cognitive impairment in PD patients in a large, nationwide population, and found that female attained significantly worse scores for Clock Drawing Test, though no gender difference was presented on total MMSE scores. Our study found that female patients seemed to have lower cognition scores of MMSE and higher scores of identification from ADAS-cog, which suggested worse cognitive performance. Different assessments might be an important issue for the inconsistent results. Previously reported gender differences on sleep mainly presented in rapid eye movement behavior disorder (RBD) [21], and there were rare data on sleep quality. However, we did not find gender differences on sleep quality, constipation and sensory complaints.

For motor symptoms, no significant gender differences were found, neither motor scores nor phenotype, suggesting gender itself might not have influence on motor symptoms at least in early stage of the disease. This could be explained by early disease duration in our population, since Lyons et al. [11] found that these motor differences were significant only in PD patients with greater than 5-year-disease duration.

The mechanism for gender differences on PD symptoms remains unclear. Estrogen has been suggested to play a role, and might have a neuroprotective effect on brain dopaminergic pathways [21]. However, there is no consensus on the exact mechanism. Our study supported that gender might play an important role in depression and cognition in early PD. While the role of estrogen in PD development and progression need to be further investigated.

The major limitation of our study is that we only focused on several specific NMS rather than extensive screening. However, the screening tool for NMS (NMSQ) has been published in 2006, and was not available when the trial was initiated. Moreover, focusing on specific NMS scales could define the NMS more accurately. Another limitation is the origin of trial subjects, which might cause selection bias. However, inclusion criteria of the trial included consecutive de novo PD patients during the screening period, which might minimize the selection bias. But the results should be applied with caution with the fact that we only enrolled PD patients with MMSE ≥24 at baseline of the trial. Since it was a cross-sectional study, whether the gender differences would present with disease progression and drug usage still needs to be further studied.

In conclusion, female early PD patients might be more depressed and have worse cognition performance, but the gender differences are not apparent on motor and other non-motor symptoms. Management for early PD patients should take these differences into consideration, and clinical observations are needed to assess the gender effects on disease progression and medication.

References

van Rooden SM, Colas F, Martinez-Martin P, Visser M, Verbaan D, Marinus J, Chaudhuri RK, Kok JN, van Hilten JJ (2011) Clinical subtypes of Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 26(1):51–58

Chaudhuri KR, Healy DG, Schapira AH (2006) Non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease: diagnosis and management. Lancet Neurol 5(3):235–245

Baldereschi M, Di Carlo A, Rocca WA, Vanni P, Maggi S, Perissinotto E, Grigoletto F, Amaducci L, Inzitari D (2000) Parkinson’s disease and parkinsonism in a longitudinal study: two-fold higher incidence in men. ILSA Working Group. Italian Longitudinal Study on Aging. Neurology 55(9):1358–1363

Bower JH, Maraganore DM, McDonnell SK, Rocca WA (1999) Incidence and distribution of parkinsonism in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1976–1990. Neurology 52(6):1214–1220

Schrag A, Ben-Shlomo Y, Quinn NP (2000) Cross sectional prevalence survey of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease and Parkinsonism in London. BMJ 321(7252):21–22

Haaxma CA, Bloem BR, Borm GF, Oyen WJ, Leenders KL, Eshuis S, Booij J, Dluzen DE, Horstink MW (2007) Gender differences in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 78(8):819–824

Baba Y, Putzke JD, Whaley NR, Wszolek ZK, Uitti RJ (2005) Gender and the Parkinson’s disease phenotype. J Neurol 252(10):1201–1205

Ehrt U, Bronnick K, De Deyn PP, Emre M, Tekin S, Lane R, Aarsland D (2007) Subthreshold depression in patients with Parkinson’s disease and dementia–clinical and demographic correlates. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 22(10):980–985

Accolla E, Caputo E, Cogiamanian F, Tamma F, Mrakic-Sposta S, Marceglia S, Egidi M, Rampini P, Locatelli M, Priori A (2007) Gender differences in patients with Parkinson’s disease treated with subthalamic deep brain stimulation. Mov Disord 22(8):1150–1156

Hariz GM, Lindberg M, Hariz MI, Bergenheim AT (2003) Gender differences in disability and health-related quality of life in patients with Parkinson’s disease treated with stereotactic surgery. Acta Neurol Scand 108(1):28–37

Lyons KE, Hubble JP, Troster AI, Pahwa R, Koller WC (1998) Gender differences in Parkinson’s disease. Clin Neuropharmacol 21(2):118–121

Rojo A, Aguilar M, Garolera MT, Cubo E, Navas I, Quintana S (2003) Depression in Parkinson’s disease: clinical correlates and outcome. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 10(1):23–28

Fernandez HH, Lapane KL (2002) Predictors of mortality among nursing home residents with a diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. Med Sci Monit 8(4):CR241–CR246

Galvin JE, Pollack J, Morris JC (2006) Clinical phenotype of Parkinson disease dementia. Neurology 67(9):1605–1611

Scaglione C, Vignatelli L, Plazzi G, Marchese R, Negrotti A, Rizzo G, Lopane G, Bassein L, Maestri M, Bernardini S, Martinelli P, Abbruzzese G, Calzetti S, Bonuccelli U, Provini F, Coccagna G (2005) REM sleep behaviour disorder in Parkinson’s disease: a questionnaire-based study. Neurol Sci 25(6):316–321

Martinez-Martin P, Falup Pecurariu C, Odin P, van Hilten JJ, Antonini A, Rojo-Abuin JM, Borges V, Trenkwalder C, Aarsland D, Brooks DJ, Ray Chaudhuri K (2012) Gender-related differences in the burden of non-motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol 259(8):1639–1647

Solla P, Cannas A, Ibba FC, Loi F, Corona M, Orofino G, Marrosu MG, Marrosu F (2012) Gender differences in motor and non-motor symptoms among Sardinian patients with Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Sci 323(1–2):33–39

Picillo M, Amboni M, Erro R, Longo K, Vitale C, Moccia M, Pierro A, Santangelo G, De Rosa A, De Michele G, Santoro L, Orefice G, Barone P, Pellecchia MT (2013) Gender differences in non-motor symptoms in early, drug naive Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol 260(11):2849–2855

Jankovic J, McDermott M, Carter J, Gauthier S, Goetz C, Golbe L, Huber S, Koller W, Olanow C, Shoulson I et al (1990) Variable expression of Parkinson’s disease: a base-line analysis of the DATATOP cohort. The Parkinson Study Group. Neurology 40(10):1529–1534

Radloff LS (1977) The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Measure 1(3):385–401

Miller IN, Cronin-Golomb A (2010) Gender differences in Parkinson’s disease: clinical characteristics and cognition. Mov Disord 25(16):2695–2703

Picillo M, Erro R, Amboni M, Longo K, Vitale C, Moccia M, Pierro A, Scannapieco S, Santangelo G, Spina E, Orefice G, Barone P, Pellecchia MT (2014) Gender differences in non-motor symptoms in early Parkinson’s disease: a 2-years follow-up study on previously untreated patients. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2014.04.023

Riedel O, Klotsche J, Spottke A, Deuschl G, Förstl H, Henn F, Heuser I, Oertel W, Reichmann H, Riederer P, Trenkwalder C, Dodel R, Wittchen HU (2008) Cognitive impairment in 873 patients with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Results from the German Study on Epidemiology of Parkinson’s Disease with Dementia (GEPAD). J Neurol 255(2):255–264

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2012AA02A514), the National Basic Research Development Program of China (2011CB504101), Ministry of Health (201002011), and the Beijing High Standard Health Human Resource Cultural Program in Health System (2009e1e12).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

The members of Chinese Parkinson Study Group are listed in Appendix.

Appendix: Members of Chinese Parkinson Study Group (CPSG)

Appendix: Members of Chinese Parkinson Study Group (CPSG)

Piu Chan (Xuanwu Hospital of Capital Medical University), Yanming Xu (West China Hospital of Sichuang University), Jun Xu (The Affiliated Gulou Hospital of Nanjing University), Yuming Xu (The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University), Chunfeng Liu (The Second Affiliated Hospital of Suzhou University), Zhenyu Wang (The Third Affiliated Hospital of Henan University of Traditional Chinese Medicine), Ping Wang (The Inner Mongolian People’s Hospital), Guohua Hu (The Second Affiliated Hospital of Jilin University), Weizhi Wang (The Second Affiliated Hospital of Harbin University), Baorong Zhang (The Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University), Zhanhua Liang (The First Affiliated Hospital of Dalian University), Anmu Xie (The Affiliated Hospital of Qindao University), Shengdi Chen (The Affiliated Ruijin Hospital of Shanghai Jiaotong University), Beisha Tang (Xiangya Hospital of Central Southern University), Benyan Luo (The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University), Wen Lü (The Affiliated Sir Sun Yat-Sen Hospital of Zhejiang University), Shenggang Sun (The Affiliated Union Hospital of Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology), Ming Shao (The First Affiliated Hospital of Guanzhou Medical College), Tao Feng (The Affiliated Tiantan Hospital of Capital Medical University), Zhuolin Liu (The First Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University), Yiming Liu (Qilu Hospital of Shangdong University), Qinyong Ye (The Affiliated Union University of Fujian Medical University), Haibo Chen (Beijing Hospital), Xinhua Wan (Peking Union Medical College Hospital), Xia Sheng (The Affiliated Hospital of Xuzhou Medical College).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Song, Y., Gu, Z., An, J. et al. Gender differences on motor and non-motor symptoms of de novo patients with early Parkinson’s disease. Neurol Sci 35, 1991–1996 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-014-1879-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-014-1879-1