Abstract

Fusiform basilar aneurysm is a rare condition with elevated mortality within a few days if untreated. On the basis of clinical course, the fusiform aneurysm can be distinguished in an acute type, such as dissecting aneurysm, which usually causes subarachnoid hemorrhage or cerebral ischemia and in a chronic type with a relatively slow growth, which may evolve into a giant aneurysm leading to serious complications. We report a case of an 80-year-old man with a surgically untreated fusiform aneurysm that evolved into a giant aneurysm of the basilar artery within 4 years. The patient presented recurrent ischemic events involving the posterior circulation without aneurysmal rupture or bleeding.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The “fusiform” is the rarest form of basilar aneurysm characterized by dilatation and elongation of an artery [1]. Fusiform aneurysm can be acute or chronic on the basis of clinical course [2]. Dissecting aneurysm is the acute type and presents an unfavorable outcome because of subarachnoid hemorrhage or cerebral ischemia [2, 3]. The chronic type rarely bleeds and more frequently may cause stroke or transient ischemic attack through several mechanisms: distension and distortion at the branching points as well as adjacent arteries, vasospasm, hemodynamic mechanisms, distal embolism from thrombus formed in the fusiform aneurysm, or occlusion of the perforating pontine arteries due to thrombosis within the aneurysm [4]. The natural course of chronic fusiform aneurysm is a slow progression to giant aneurysm, which is defined as intracranial aneurysm with diameter larger than 25 mm [5].

We report a case of old man with fusiform evolving to unruptured giant aneurysm in the basilar artery which raises several questions related to the pathogenesis of recurrent ischemic events and medical management.

Case report

First admission

An 80-year-old man acutely developed left hemiparesis, vertigo, gait ataxia and dysarthria. The symptoms regressed spontaneously after about 2 h. He had a past medical history of hyperlipidemia and he was treated with statin and ticlopidine. Blood pressure, electrocardiogram, transthoracic echocardiography and extracranial Doppler sonography were normal. Brain CT showed old ischemic areas. Diffusion-weighted (DWI) MR was negative, while MR angiography (MRA) showed a fusiform aneurism of the basilar artery without intra-arterial thrombus. The ongoing antiplatelet therapy was replaced with clopidogrel.

Second admission

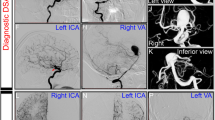

A month after the first transient ischemic attack (TIA), the patient presented acute ischemic stroke of posterior circulation with right hemiparesis, vertigo, gait ataxia, dysarthria, dysphagia, and rotary nystagmus. Patient’s blood pressure was 130/70 mmHg and heart rhythm was sinus. DWI MR showed recent ischemic lesions of left pons, cerebellar hemisphere, and cerebellar peduncle. Aspirin treatment was started in association to clopidrogel. Three days after ischemic stroke, the patient acutely developed right hemiplegia. The blood pressure was stable and heart rhythm was sinus. Brain CT was negative for recent ischemic lesions. The patient underwent intravenous (IV) rt-PA within 2 h from symptoms onset. Right hemiplegia was regressed 2 h after IV thrombolysis. MR with gadolinium and time-of-flight (TOF) MRA showed a partial thrombosed dissecting aneurysm of the basilar artery with intimal flap, double lumen and recent hemosiderin deposition (Figs. 1a–b, 2). Anticoagulation therapy was started.

Axial MR images with gadolinium show a partial thrombosed dissecting aneurysm of the basilar artery. The arrow indicates intimal flap and double lumen of the fusiform basilar dissection (a). The dotted line delimits the primitive lumen (diameter 7 mm), while the solid line indicates the external wall of thrombosed aneurysm (large diameter 9 mm) with recent hemosiderin deposition (hyperintense signal) (b)

Third admission

Three weeks after IV thrombolysis, the patient was admitted to hospital for an episode lasting about 30 min characterized by paresthesia of right upper limb, dysarthria and mouth-angle deviation. The International Normalized Ratio (INR) range was in therapeutic range. During this admission, the patient presented several episodes lasting about an hour each with spontaneous regression characterized by disorder sensory-motor of right upper limb, sometimes associated with dysarthria and/or mouth-angle deviation. An electroencephalogram performed during one of these episodes was negative. Brain CT and DWI MR were negative.

Fourth admission

Four years after the first event, the patient acutely developed left hemiplegia, vertigo, gait ataxia, dysarthria, and dysphagia. The INR range was not therapeutic. MR documented an important increase of aneurysm dimensions with periluminal thrombus causing compression and atrophy of pons and midbrain (Fig. 3a–b), whereas the lumen size of basilar artery was preserved on TOF MRA (Figs. 4a–b, 5). DWI MR were negative for recent ischemic lesions. The patient’s symptoms improved after a few days.

Axial TOF MRA images show a giant aneurysm of the basilar artery. The arrow indicates the primitive lumen of giant aneurysm (a). The dotted line delimits the primitive lumen with preservation of size (diameter 9 mm), while the solid line indicates the external wall of thrombosed aneurysm with increase of dimensions (large diameter 31 mm) (b)

Discussion

Fusiform aneurysm is most common in the elderly with severe atherosclerosis. However, the origin of fusiform aneurysm is unclear [1]. Also, alternative hypotheses have been proposed for the formation of a fusiform aneurysm, including a congenital anomaly, inflammatory vasculopathy, mechanical injury by poststenotic turbulence, intimal disruption from arterial dissection, and severe reticular fiber deficiency in the muscle layer [1]. Fusiform basilar aneurysms are divided into small (<12 mm) which are usually asymptomatic, large (12–25 mm) which may cause occlusion of the perforating arteries or distal embolism, and giant (larger than 25 mm) aneurysms [6, 7]. Clinically, the giant aneurysm usually presents as a space-occupying lesion with a compressive effect on posterior fossa structures, or posterior circulation stroke due to the occlusion of penetrating vessels, or distal embolism from thrombus in the aneurysm lumen [8, 9]. Alternative mechanisms include compression, vasospasm, hemodynamic mechanisms in view of the poor cerebral collateral circulation, vascular dysautoregulation of the brainstem-cerebellar regions that are more sensitive to orthostatic hypotension [9].

We reported a case of a 80-year-old man with untreated fusiform aneurysm evolving to giant aneurysm without rupture or bleeding. The patient was admitted four times because of several recurrent ischemic events whose pathogenetic mechanisms raised interesting questions.

First admission

The clinical manifestation of the TIA was suggestive of an ischemic event in the posterior circulation. The MRA showed a small fusiform aneurysm of the basilar artery without intra-arterial thrombus. Therefore, it was possible that TIA was most likely due to arterial distension–distortion, or vasospasm or hemodynamic mechanisms than intra-arterial thrombosis or embolism.

Second admission

Two strokes involving posterior circulation occurred within 3 days, the second had been favorably treated with IV thrombolysis. It was possible that ischemic events were related to distal arterial embolism or occlusion of the perforating pontine and cerebellar arteries due to partial thrombosis with recent hemosiderin deposition in the dissecting fusiform basilar aneurysm. Nevertheless, the diagnosis of dissection of fusiform basilar aneurysm was based on MR with gadolinium and MRA, but not cerebral angiography because the patient refused to perform the intra-arterial procedure.

Third admission

The short-lasting episodes with spontaneous resolution were suggestive of TIA in the posterior circulation. The patient was under anticoagulant therapy and the INR was in therapeutic range, and then it was possible that recurrent TIAs were most likely due to arterial distension–distortion, or vasospasm or hemodynamic mechanisms than intra-arterial thrombosis or embolism.

Fourth admission

An ischemic stroke involving the posterior circulation occurred after 4 years from symptoms onset. DWI MR did not show recent ischemic lesions, whereas MRA showed an important increase of aneurysm dimensions with periluminal thrombus, but with preservation of lumen size. This could be due to a compressive mechanism of the large mass aneurysm and/or to atrophy of pons and midbrain which may have masked any ischemic lesion.

Our case is peculiar because a follow-up of 4 years is unusual in a patient with chronic fusiform aneurysm in the basilar artery. According to the medical literature, the natural history is frequently unfavorable with up to 80% mortality rate within a few years if untreated. However, the clinical outcome remains considerably variable [7], and the mechanisms of progressive growth to giant aneurysm are unclear. It has been suggested that the progression of chronic fusiform aneurysm could be an expression of fragmentation of internal elastic lamina followed by intimal hyperplasia or neovascularization with the subsequent recurrent intramural hemorrhage within the aneurysmal wall [1, 4, 6, 7].

In addition, although the prevailing opinion is that giant aneurysm may rupture, our case confirms that in the real world this doesn’t happen. In fact, bleeding due to rupture or dissection of giant aneurysm is extremely rare. In addition, other cases in which elderly patients with unruptured giant aneurysm have recently been reported [3, 10].

Finally, our case is emblematic because of several questions related to the medical management of untreated fusiform aneurysm which remain controversial [11]. The therapeutic strategy is individually selected and the clinical outcome varies considerably [11]. Antiplatelet medications are recommended for primary stroke prophylaxis in the presence of fusiform aneurysm found incidentally, whereas anticoagulation may be required more often in patients with the frequent recurrence of stroke or TIA [4]. Our patient was treated with a conservative therapy because of old age; also, the localization of aneurysm represented high-risk conditions for the surgical indication [9]. Nevertheless, both antiplatelet and anticoagulant medications were not fully protective for stroke or TIA recurrence suggesting that ischemic events in fusiform and giant aneurysms may recognize different mechanisms beyond the thrombosis or embolism.

Conclusion

Our case is emblematic because of the progressive growth of untreated chronic fusiform aneurysm to giant aneurysm presenting with the recurrent ischemic events without rupture or bleeding.

References

Nakayama Y, Tanaka A, Kumate S, Tomonaga M, Takebayashi S (1999) Giant fusiform aneurysm of the basilar artery: consideration of its pathogenesis. Surg Neurol 51:140–145

Nakatomi H, Segawa H, Kurata A, Shiokawa Y, Nagata K, Kamiyama H, Ueki K, Kirino T (2000) Clinicopathological study of intracranial fusiform and dolichoectatic aneurysm. Insight on the mechanism of growth. Stroke 31:896–900

Sarica FB, Cekinmez M, Tufan K, Sen O, Erdoğan B, Altinörs MN (2008) A non-bleeding complex intracerebral giant aneurysm case: case report. Turk Neurosurg 18:236–240

Sharfstein SR, Wu E (2001) Case of unusual presentation of fusiform aneurysm of the basilar artery. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 10:161–165

Lubicz B, Leclerc X, Gauvrit JY, Lejeune JP, Pruvo JP (2004) Giant vertebrobasilar aneurysms: endovascular treatment and long-term follow-up. Neurosurgery 55:316–326

Yasui T, Komiyama M, Iwai Y, Yamanaka K, Nishikawa M, Morikawa T (2001) Evolution of incidentally-discovered fusiform aneurysms of the vertebrobasilar arterial system: neuroimaging features suggesting progressive aneurysm growth. Neurol Med Chir 41:523–528

Wakhloo AK, Mandell J, Gounis MJ, Brooks C, Linfante I, Winer J, Weaver JP (2008) Stent-assisted reconstructive endovascular repair of cranial fusiform atherosclerotic and dissecting aneurysms: long-term clinical and angiographic follow-up. Stroke 39:3288–3296

Steel JG, Thomas HA, Strollo PJ (1982) Fusiform basilar aneurysm as a cause of embolic stroke. Stroke 13:712–716

Steinberger A, Ganti SR, McMurtry JG 3rd, Hilal SK (1984) Transient neurological deficits secondary to saccular vertebrobasilar aneurysms. Report of two cases. J Neurosurg 60:410–413

Nakase H, Shin Y, Kanemoto Y, Ohnishi H, Morimoto T, Sakaki T (2006) Long-term outcome of unruptured giant cerebral aneurysms. Neurol Med Chir 46:379–386

Velilla NM, Saralegui FI et al (2009) Gait impairment and dysphagia due to a giant basilar aneurysm in a nonagenarian. Rev Esp Geriatr Gerontol 44:159–161

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cappellari, M., Tomelleri, G., Piovan, E. et al. Chronic fusiform aneurysm evolving into giant aneurysm in the basilar artery. Neurol Sci 33, 111–115 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-011-0628-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-011-0628-y