Abstract

Recent studies focusing on the interspecific communicative interactions between humans and dogs show that owners use a special speech register when addressing their dog. This register, called pet-directed speech (PDS), has prosodic and syntactic features similar to that of infant-directed speech (IDS). While IDS prosody is known to vary according to the context of the communication with babies, we still know little about the way owners adjust acoustic and verbal PDS features according to the type of interaction with their dog. The aim of the study was therefore to explore whether the characteristics of women’s speech depend on the nature of interaction with their dog. We recorded 34 adult women interacting with their dog in four conditions: before a brief separation, after reuniting, during play and while giving commands. Our results show that before separation women used a low pitch, few modulations, high intensity variations and very few affective sentences. In contrast, the reunion interactions were characterized by a very high pitch, few imperatives and a high frequency of affectionate nicknames. During play, women used mainly questions and attention-getting devices. Finally when commanding, women mainly used imperatives as well as attention-getting devices. Thus, like mothers using IDS, female owners adapt the verbal as well as the non-verbal characteristics of their PDS to the nature of the interaction with their dog, suggesting that the intended function of these vocal utterances remains to provide dogs with information about their intentions and emotions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Humans and dogs share a long history, as dogs are believed to be the first species to have been domesticated, approximately 32 thousand years ago (Thalmann et al. 2013). According to several surveys, dogs are now often considered as “part of the family” by their owners who see themselves as “pet parents” rather than as “owners” (Taylor 2006; Del Monte Foods 2011) and provide interspecific nurturing and protective behaviour towards their pet dogs (Fogle 1992; Askew 1996; Archer 1997; Archer and Monton 2011). Gibson et al. (2014) compare the dogs’ integration into human families to a “child-like immersion”. The affective bond between owners and dogs mirrors the human parents–infant bond and may have a common biological basis. For instance, both owners and dogs experience an important secretion of oxytocin after a brief period of cuddling or after sharing a mutual gaze (Odendaal and Meintjes 2003; Nagasawa et al. 2009, 2015). Moreover, owners speak to their dogs using pet-directed speech (PDS), a register that strongly resembles the infant-directed speech (IDS) used by humans when talking to infants (Fernald and Simon 1984; Trainor et al. 2000; Prato-Previde et al. 2006). The specific prosody of both PDS and IDS is assumed to draw the addressee’s attention, as well as to express friendliness and affection (Trainor et al. 2000; Mitchell 2001).

PDS and IDS share syntactic and prosodic aspects that are distinct from adult-directed speech (ADS): higher fundamental frequency (also called pitch), greater pitch range, more exaggerated vowel contrast, shorter phrases, simpler grammar, repetitions and slower speech rate (Hirsh-Pasek and Treiman 1982; Burnham et al. 1998, 2002). Authors found that IDS contains hyperarticulated vowels (Burnham et al. 2002); this characteristic appears to be related to the audience’s actual or expected linguistic competence and may serve a didactic function. Xu et al. (2013) show that the degree of vowel hyperarticulation increases from ADS and PDS, to parrot-directed speech, and then to IDS. Nevertheless, other research on puppy-directed speech shows that both IDS and puppy-directed speech are more hyperarticulated than ADS which raises the possibility that IDS hyperarticulation may be more related to emotional expressiveness than to a desire to teach language (Kim et al. 2006). With regard to hyperarticulation, the comparison between PDS and puppy-directed speech remains to be done.

The prosody of IDS is known to change according to the context of the interaction with the child (Newport et al. 1977; Fernald 1989; Papoušek et al. 1990, 1991; Trainor et al. 1997, 2000). Similarly, Pongrácz et al. (2001) indicated that human–dog acoustic communication could be highly situation-dependent. However, whether speakers adjust the acoustic and verbal features according to the type of interaction when speaking to their dog has not been systematically investigated.

The aim of this study was to explore whether variations appear within PDS according to the type of interaction human and dog are involved in. Towards these ends, we focused on women–dog interaction because female owners, as previously mentioned, are more likely to use PDS than male owners (Mitchell 2004; Prato-Previde et al. 2006). We investigated both the acoustic and linguistic features of female owners’ speech as these two dimensions have been shown to be intimately related (Syrdal and Kim 2008). To do so, we analysed the speech of female owners addressing their dog in four different types of interaction: (a) before a brief separation, referred below as “separation”; (b) after a reunion, referred below as “reunion”; (c) during play, referred below as “play”; and (d) when giving commands, referred below as “commands”. Our experimental conditions are based on the Strange Situation test originally set up by Ainsworth and Wittig (1969) and designed to investigate human parent–infant attachment (Bowlby 1969). The Strange Situation procedure was adapted for studying affectional bonds of dogs towards their owners (Topál et al. 1998; Prato-Previde et al. 2003).

Based on previous studies (Fernald 1989; Trainor et al. 2000) which show that the specific features of IDS are used to transmit emotional information and that different types of IDS are used in different contexts (Fernald 1989; Trainor et al. 2000), we predicted that female owners’ PDS verbal and non-verbal features would be primarily shaped by the type of interaction. In the separation condition, we predicted that women would either (1) reassure their dog before leaving, explaining what was going to happen using mostly declarative sentence types and a soothing tone characterized by a low pitch and falling contours like IDS in a soothing context (Fernald 1989; Trainor et al. 2000) or (2) prevent the dog from coming with them, using a low pitch and flat contours with mostly imperative sentence types, like IDS in a prohibition context (Fernald 1989; Trainor et al. 2000). In contrast, in the reunion condition, considered as one of the most positive human–dog interactions (Rehn et al. 2013), we expected that women would speak with a high pitch and increased pitch variation and predominantly use affective sentence types. Regarding the play context, research investigating at human vocalizations to dogs found them to be highly repetitive and imperative suggesting that owners were attempting to “control the dog”, i.e. to avoid unwanted behaviours (Mitchell and Edmonson 1999). A recent study indicates there are different types of play which differ in their form and affect content and that accordingly dog owners’ vocalizations vary in their positive and neutral affect (Horowitz and Hecht 2016). We thus expected women to speak with mostly imperative sentence types, using few declaratives and questions, while prosodic features were expected to vary depending on what type of play owner and dog are involved in. We predicted that both during play and when commanding, women would use a high frequency of repetitions with mainly verb and attention-getting devices as these two conditions imply a succession of actions, and thus the necessity to get and maintain the dog’s attention towards the activity (Rogers et al. 1993). Finally in the command condition, we expected women to use a “commanding tone” characterized by a low pitch and flat contours with mostly imperative sentence types. This imperative style should be different from imperatives in play which are assumed to function to encourage the dog to continue playing (Mitchell 2001).

Finally, some studies suggest that people who are not parents tend to see their dog as a family member significantly more than people who have children (Berryman et al. 1984; Albert and Bulcroft 1988; Kidd and Kidd 1989; Poresky and Daniels 1998; Taylor 2006). Consequently, we predicted that owners who do not have children would speak with enhanced PDS prosodic features compared to those who have children.

Methods

Subjects and data collection

The study took place at the Ecole Nationale Vétérinaire d’Alfort, France (ENVA) between May and July 2013. The following protocol was approved in April 2013 by the Ethics Committee for Clinical Research (Comité d’Ethique en Recherche Clinique, ComERC) of ENVA. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Participants were debriefed about the more specific aims of the study at the end of the experiment. Forty-five owner and dog dyads were recruited from the waiting room of the preventative medicine consultation of the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Vétérinaire d’Alfort (CHUVA) and through veterinary students’ social networks. Participants whose dogs presented significant health problems, aggressiveness towards people, sight or hearing problems were not tested. The aim of the research was presented to the participants as follows: “we would like to observe the behaviour of dogs placed in a new environment during different situations of interaction with their owner”.

Out of 45 women that took part into the experiment, we excluded 11 women that did not speak in all conditions (see below for detailed information about conditions). Participants were 34 women aged 18–56 with an average age of 35.5 years (±2.2). Dogs were 4.2 years (±7.6), 17 were males and 17 were females. Only 6 out of 34 dogs were under 1 year old. We included puppies from the age of 3 months as this age corresponds to the end of the socialization period (Markwell and Thorne 1987).

The study was performed in a 24 m2 room. The experiment was filmed using a Canon (Legria HF R306) video recorder mounted on a 1.1 m tripod placed at the back-centre of the room. The owner was equipped with a lapel microphone (Olympus ME-15) connected to a digital recorder (MARANTZ PMD620). Two female experimenters were involved in the study. One of them carried out the study; the other one was only present during a short period of time, when the female owner was briefly separated from her dog (see below), in order to reduce the stress of the dog.

Procedure

Preliminary phase

The owner was asked to specify her name, age, parental status as well as her dog’s name, age and sex. The dog was let free to explore the room. This preliminary phase enabled the dog to acclimatize to its new environment. Two experimenters were present in the room during this phase, but they did not interact with the dog. The purpose of the study was presented to the participant as aiming to explore dogs’ behaviour when placed in a new environment in different situations of interaction with their owners. The experimenter explained to the owner that the four steps of the study corresponded to four conditions of interaction with her dog: separation, reunion, play and commands (Fig. 1). The total duration of this preliminary phase was about 5 min.

Experimental phases

The aim of the four conditions of interaction was to audio- and video-record natural and spontaneous speech from the owner to the dog. The owner was simply asked to interact with the dog in the same manner as she would at home. By not controlling what owners said to the dogs, we aimed at enhancing the ecological validity of our observations. Indeed, more standardized conditions may have limited or biased the vocal expression of the owner. The only guideline we gave to owners was to play and give commands to their dogs for 1 min. Separation and reunion were not time controlled and were generally brief (30 s in average). The order of testing was (1) separation, (2) reunion, (3) play and (4) commands. The first two experimental phases were similar to Ainsworth Strange Situation procedure (Ainsworth and Wittig 1969) and consisted of short episodes of separation and reunion with the owner. For ethical reasons, because the experience of being separated from the owner can be considered a source of distress for adult dogs (Palestrini et al. 2005), we decided to systematically place the play condition after the episodes of separation and reunion, in order to provide comfort to the potentially mildly distressed dog.

-

1.

Separation condition The owner and one of the experimenters left the room for 3 min for a short walk around the building while the second experimenter stayed with the dog. Before leaving, the owner was asked to interact with her dog as she usually does: she was allowed to talk or to pet the dog as she normally would. The experimenter that stayed with the dog was always the same person and she was instructed to strictly refrain from interacting with the dog. The separation interactions were not time limited and lasted about 30 s. During the 3 min walk, the owner and the experimenter interacted freely, which allowed us to record adult-directed speech. Because the general conditions during this recording were quite different from those of the experimental phrases, we did not retain these data in the main analysis. However, these data were specifically used for a point of statistical clarification (results section, acoustic analyses, effect of parental status).

-

2.

Reunion condition the owner and the experimenter came back reentered the room and the owner was free to interact with her dog as though she had just returned from work or shopping. The interaction lasted an average of 30 s until the owner stopped the interaction with her dog and looked at the experimenter or asked her about the next step.

-

3.

Play condition The owner was asked to play with her dog for 1 min. There were no specific rules regarding how the owner could play with the dog. Different toys were available in the room and offered to the owners like ropes, tennis balls, cuddly toys, etc. Owners could also use their own toys.

-

4.

Commands condition The owner was asked to give commands for 1 min, whether the dog obeyed or not. The owner was not asked to give specific commands, but to interact as usual. It was, however, specified that she could repeat the same command as many times as she wanted. The owner was allowed to reward the dog by voice (congratulations) or with treats at her disposal.

Data analysis

Acoustic analysis

During each condition, women’s utterances were generally short, lasting a few seconds, and reiterated after pauses. For the purpose of our analyses, we extracted all fragments of speech directed to the dog and chained them in order to form a unique audio sequence per condition, using Audacity software (2.0.3). In the “commands” condition, in order to focus specifically on the acoustic properties of the commands, we excluded the frequent vocal congratulations that came after the dog obeyed a command.

We performed acoustic analyses using a script in Praat software (5.3.50) on the following measures: (a) mean F0: calculated as the average fundamental frequency over the duration of the signal and (b) F0CV: the coefficient of variation of F0 over the duration of the signal, estimated as the standard deviation of F0 divided by mean F0; it is a measure of the intonation (F0 contour variations). We also calculated (c) IntCV: the coefficient of variation of the intensity contour (intensity corresponds to the energy in the sound), as modulation of fundamental frequency has been shown to inevitably co-vary with distinctive patterns of intensity (Sokol et al. 2005).

Verbal analysis

Owners’ speeches utterances were independently transcribed by two investigators. We also noted non-verbal vocal sounds such as whistles. Lapel microphones enabled a high audio recording quality, even when owners whispered. Agreement in word and non-word identifications between the two investigators was 95%.

In a first step, we explored whether the interaction context had an influence on the sentence types used by owners when talking to their dog. The entire original corpus was examined, and utterances were categorized following the sentence types used by Syrdal and Kim (2008): imperative, interrogative, affective and declarative (assertive), considered as four broad modes of enunciation reflecting the speaker’s cognitive attitude to the content. The beginning and end of sentences were determined on the basis of intonation and pauses. We distinguished four types of sentences on the basis of intonation, meaning of the words/sentences and their context: (1) imperative sentence type (i.e. “Sit!”). We also looked for imperatives disguised as questions (i.e. “Tu me donnes la balle?”, English translation: “You give me the ball?”) that were not “a request for information, but a directive” (Mitchell and Edmonson 1999). (2) Interrogative sentence type were requests for information (i.e. “Quel jouet tu veux?”, English translation: “Which toy do you want?”. (3) Affective sentence type included mainly positive exclamations: stock phrases and common expressions (i.e. “A tout à l’heure!”, “Bonjour/Coucou”, English translation: “See you!” or “Hi!”), interjections (i.e. “hey!”, “oh!”, “allez!”, “hop!”) compliments (i.e. “t’es belle/t’es beau!”, English translation: “You pretty girl/boy!”) or verbal praising/congratulations (i.e. “bravo !”, “bon chien !”, English translation: “Good girl/boy!”). Tag questions (i.e. “C’est quoi ça?!”, English translation: “What’s this?”) and post-completers (“Hein?”, English translation: “You do?”) (Mitchell and Edmonson 1999) were classed as affective sentence type as the owner was not expecting an answer but was trying to stimulate the dog. (4) Declarative sentence type was usually used by owners when talking in place of the dog or expressing the dog’s feelings (i.e. “Hmm, je sens une odeur qui n’est pas la mienne”, English translation: “Hmm, I am sensing a smell that’s not mine”). Moreover, we measured the occurrence of particular utterances that did not meet the precedent sentence types criteria: (5) attention-getting devices (AGD) were considered, as calling the dog’s name and non-verbal sounds used to catch the dog’s attention (i.e. “qqq” or whistle). (6) Affectionate nicknames given to the dog were the last (i.e. “ma douce”, English translation: “sweety”).

In a second step, sentences were fractionated into words and the total of different words used by owners was extracted in each of the conditions. We first investigated words’ repetitions by calculating the total number of words used with and without individual repetitions and we performed the ratio between the two (see “Results”).

Then, in order to explore whether the interaction context had an influence on the grammatical categories of words used by owners, we selected words that were only used at least by five participants in each condition and we classified the words into grammatical categories: nouns, pronouns, verbs, adverbs, interjections, prepositions, conjunctions, or articles. In this analysis, because some owners had a tendency to repeat the same words in conditions, repetitions of the same word by the same owner in the same condition were discarded.

Statistical analysis

Acoustic analysis

One-way repeated measure ANOVAs were performed to test the influence of the different conditions (separation, reunion, play and commands) on the owner PDS features; the sample size was n = 34.

In addition, a two-way repeated measure ANOVA was performed to test the interaction between the variables “condition” and “parental status”. Post hoc analyses were performed using Bonferroni-corrected paired t test (Sokal and Rohlf 1995). Mann–Whitney tests were performed to compare data from mothers versus non-mothers. The sample size for these analyses was n = 33, because information about the parental status of one participant was missing. Results are reported as mean ± SE (standard error). Two-tailed tests were used throughout.

Verbal analysis

Because the data did not follow statistical normality (Shapiro–Wilk test for normality p < 0.05) and could not be normalized with standard transformations, Friedman repeated measures ANOVAs on ranks were performed to test the influence of the condition on the use of different sentence types and particular utterances (Siegel and Castellan 1988). Post hoc analyses were performed using Tukey’s HSD, accounting for multiple comparisons and maintaining experiment-wise alpha at the specified level (0.05) (Maxwell and Delaney 2004).

Moreover, Chi-square tests were performed to explore the distribution of the grammatical categories of words used in each condition. Two-tailed tests were used throughout. All statistical analyses were performed using SigmaPlot 13.0 software.

Results

Acoustic analyses

Mean F0

There was a significant effect of the condition on mean F0 (one-way RM ANOVA, F (3, 33) = 2.92, p = 0.038). Women used a higher-pitched voice in the reunion condition compared to the separation condition: Bonferroni paired t test = 2.88, p = 0.029.

Coefficient of variation of F0 (F0CV)

There was a significant effect of the condition on the F0CV [F (3, 33) = 12.05, p < 0.001]. Women had a lower F0CV in the separation condition compared to all conditions: separation versus reunion: t = 5.58, p < 0.001, separation versus play: t = 4.60, p < 0.001, separation versus commands: t = 4.08, p < 0.001.

Coefficient of variation of the intensity contour (intCV)

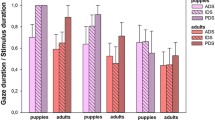

There was a significant effect of the condition on the IntCV [F (3, 33) = 6.05, p < 0.001]. Women showed a greater IntCV in the command condition compared to play: t = 3.90, p = 0.001 and compared to reunion: t = 2.99, p = 0.021 (Fig. 2).

Effect of parental status

The data analysis revealed a significant main effect of the owners’ parental status and of the condition of interaction on mean F0; no significant interaction effect was found, (two-way RM ANOVA, parental status effect, F (1, 31) = 4.33, p = 0.046; condition effect, F (3, 31) = 3.03, p = 0.033; interaction, F (3, 31) = 0.10, p = 0.962). Non-mothers spoke with a higher-pitched voice than mothers, with, respectively, M = 305.6 ± SE = 7.8 and M = 278.5 ± SE = 10.4). No significant effect of the parental status was found on other acoustic parameters.

A Mann–Whitney comparison test showed that non-mothers (n = 21, M = 28.71 ± SE = 2.2) were also younger than mothers (n = 12, M = 46.0 ± SE = 2.4): U = 30, p < 0.001. As such, we cannot rule out that the effect of parental status on mean F0 was affected by the age of the speaker. We attempted to clarify this question by analysing female owners’ speech directed to the experimenter (adult-directed speech). This was possible because owners still wore the lapel microphone during the separation condition. A Mann–Whitney comparison test did not show any difference between non-mothers and mothers on mean F0 in adult-directed speech (U = 86, p = 0.139, with, respectively, M = 246.45 ± SE = 7.6 and M = 227.23 ± SE = 11.7).

Verbal analyses

Sentence types

Imperative

There was a significant effect of the condition on the use of imperative sentence type [Friedman, χ 23 (n = 34) = 61.92, p < 0.001]. Owners used significantly fewer imperative sentences in the reunion condition compared to all conditions and significantly more imperative sentences in the commands condition compared to all conditions: commands versus reunion: q = 10.69, p < 0.05; commands versus separation: q = 6.31, p < 0.05; commands versus play: q = 3.72, p < 0.05; play versus reunion: q = 6.97, p < 0.05; separation versus reunion: q = 4.38, p < 0.05.

Interrogative

There was a significant effect of the condition on the use of interrogative sentence type [χ 23 (n = 34) = 25.05, p < 0.001]. Owners used significantly more interrogative sentences in the play condition compared to the separation condition (q = 5.25, p < 0.05) and compared to the commands condition (q = 4.18, p < 0.05).

Affective

There was a significant effect of the condition on the use of affective sentence type [χ 23 (n = 34) = 41.71, p < 0.001]. Owners used significantly fewer affective sentences in the separation condition compared to all conditions: separation versus commands: q = 7.9, p < 0.05; separation versus reunion: q = 7.37, p < 0.05; separation versus play: q = 5.98, p < 0.05.

Declarative

There was no significant effect of the condition on the use of declarative sentence type [χ 23 (n = 34) = 4.54, p = 0.209] (Fig. 3).

Effect of the condition of interaction (separation, reunion, play and commands) on the sentence types used by female owners: a imperative, b interrogative, c affective, d declarative, e attention-getting devices and f nickname. Letters are used to indicate significance: the presence of a same letter above bars indicates a non-significant difference

Concerning particular utterances, there was a significant effect of the condition on the use of attention-getting devices (AGD) [χ 23 (n = 34) = 24.66, p < 0.001). Owners used significantly more AGD in commands and play conditions compared to the other conditions: commands versus separation: q = 3.72, p < 0.05; commands versus reunion: q = 5.71, p < 0.05; play versus reunion: q = 4.52, p < 0.05. There was also a significant effect of the condition on the use of nicknames [χ 23 (n = 34) = 18.89, p = 0.003]. Owners used significantly more nicknames in the reunion condition compared to the play condition (q = 3.65, p < 0.05) (Fig. 3).

Repetitions

Descriptive data from Table 1 showed that the ratio of the number of words with individual repetitions (IR) divided by the number of word without individual repetitions (IR) is close to 3. Overall, owners used a lot of repetitions. This ratio is particularly important in the commands condition (2.85) and in the play condition (2.29). Repetitions are less important in the reunion condition, with a ratio of 1.86.

Grammatical categories of words

Chi-square showed significant differences between conditions with the use of grammatical categories (Fig. 4). In separation [χ 23 (n = 34) = 30.04, p < 0.001), play [χ 23 (n = 34) = 37.64, p < 0.001) and commands [χ 23 (n = 34) = 62.05, p < 0.001), data showed that participants used principally verbs when addressing the dog. However, in the reunion condition [χ 23 (n = 34) = 8.04, p = 0.09), participants did not use a particular grammatical category, but multiple ones (interjections, adverbs, verbs and other).

Discussion

To our knowledge, the present study is the first to investigate both the verbal and non-verbal features of adult women’s speech during different types of interactions with their dogs. Speech utterances were recorded in four experimental conditions which solicit different emotions and intents from the owners: before a brief separation, after reunion, during play and giving commands. Our results show that women adapted both the verbal and non-verbal aspects of their utterances to the interaction context.

In the separation condition, female dog owners used a low-pitched voice, flat intonation contours and high voice intensity variation. Additionally, they used verbal features consistent with these acoustic parameters: a high frequency of imperatives and few affective sentences. With regard to our initial hypotheses, these results support the idea that women tried to prevent the dog to come with them using an imperative style of communication rather than a soothing style of interaction. According to our predictions, in the reunion condition women used a high-pitched voice and significantly more pitch variations. These non-verbal features were reinforced by the use of affective sentences and affectionate nicknames. Moreover, they did not use verbs or imperatives as frequently as in the other types of interactions. Thus, our findings suggest that female dog owners use a high-pitched voice when they want to express praise or affection and a low-pitched voice when they want to control the dog. This result confirms previous studies indicating that increases in mean F0 are typical of vocal expressions of enjoyment, happiness, whereas decreases in mean F0 characterize expressions of authority, irritation and anger (Bolinger 1964; Fernald 1992). Moreover, it is consistent with ethological observations highlighted by Morton (1977) that non-verbal auditory signals, in humans and non-humans, have similar functions: high tonal sounds in animals repertoires are associated with affiliative or submissive motivation while low, harsh sounds are associated with aggressive motivation. Hence, because dogs do not possess the ability of language, female dog owners emphasize non-verbal cues to convey their emotions and intents, using signal components with cross-specific value.

In the play condition, in line with our predictions, women frequently used attention-getting devices (AGD), questions and imperatives although we noticed that imperatives were more encouragements than real commands. We found a similar pattern of verbal features in the commands condition: women used a high frequency of AGD and imperatives; contrary to the play condition, they did not use questions as they were not engaged in a mutual activity and were just asking the dog to obey. In addition, women did not use a significantly low-pitched voice or flat contours. A possible interpretation is that when female owners give a command to their dog, they first attempt to draw his/her attention, using exaggerated acoustic features and then seek to maintain the dogs’ arousal and motivation throughout the activity. Female owners used prosody as an ostensive cue, i.e. as a means to alert the dog to the communication directed to them (Topál et al. 2014). Acoustic features characterized by decreasing F0 are better related to prohibition (Fernald 1989; Trainor et al. 2000), as observed in the separation condition when female owners intend to inhibit the dog’s behaviour.

The current study thus confirms that women do not rely solely on prosody when they communicate with dogs as they associate specific verbal content to the non-verbal component of their vocal signals. We observed that female owners spoke to their dog using words and constructions derived from normal speech (e.g. similar to those used in ADS), but with a limited vocabulary including frequent repetitions of isolated words or phrases. They also simplified their utterances using verbs but excluding grammatical categories that are likely to be meaningless to the dog, such as articles. Similar linguistic patterns have been identified in IDS and are believed to facilitate infant’ language comprehension and acquisition (Saint-Georges et al. 2013). When interacting with their dog, female owners may use acoustic features such as pitch modulations as a tool to highlight focal words and thus to assist words’ segmentation and recognition by dogs. As mentioned by Ohala (1984), the F0 of voice is used as a gesture which accompanies or is superimposed onto the linguistic message, in order to enhance its meaning. We suggest that women use specific linguistic and verbal patterns when speaking to their dog because they aim to teach or reinforce basic commands. Indeed, owners report that they feel that their dog understands the meaning of certain verbal utterances (Pongrácz et al. 2001). Thus, when women speak to their dogs, both the prosody and the verbal content appear to function to convent context-relevant information. Further studies should investigate whether dogs whose owners frequently use PDS are more capable of acquiring and understanding commands than dogs whose owners seldom communicate using PDS.

We also hypothesized that PDS would be influenced by the parental status of the owner, because non-parents tend to see their dog as a family member significantly more than parents. We predicted that non-mothers would present exacerbated prosodic features compared to mothers. Our results are consistent with this hypothesis: non-mothers spoke to their dog with a higher-pitched voice compared to mothers. In our sample, non-mothers were younger than mothers which may account for this result, as some authors report a decrease in voice pitch with age in adult women (Harrington et al. 2007). However, we failed to find a significant difference between non-mothers and mothers’ fundamental frequency mean in ADS in our sample. One explanation for these results could be that non-mothers have a stronger tendency to express friendliness and affection to their dogs, consistent with research indicating that people who do not live with children tend to be more attached to their dogs (Marinelli et al. 2007) and that couples without children show a particularly high degree of attachment to their pet and are more prone to consider their dog as a member of their family, even as their own child (Berryman et al. 1984; Albert and Bulcroft 1988; Kidd and Kidd 1989; Poresky and Daniels 1998; Taylor 2006; Del Monte Foods 2011).

Conclusion

Overall, our results confirm that women speaking to their dog, like mothers speaking to their babies, adapt the verbal and non-verbal features of their speech to the interaction’s context in order to provide the dog with information about their intentions and emotions. They also take into account the dog’s limited ability to understand human verbal signals and adjust their mix of speech components accordingly, using appropriate verbal content reinforced by non-verbal cues in order to enhance the dog’s comprehension and to some extent with the aim of teaching the dog some basics utterances.

While research has shown that naturally spoken IDS is associated with increased infant attention and social responsiveness compared to ADS (Dunst et al. 2012) and that IDS leads to an increase neuronal activation (Golinkoff et al. 2015) as well as to positive effects on infant language development (Liu et al. 2003; Song et al. 2010), no study has yet explored dogs’ preference for PDS. Future studies should investigate the perceptual relevance of PDS’s features from dogs’ perspective, in order to evaluate the effect of PDS on dogs’ attention, mood and ability to learn new commands.

References

Ainsworth MDS, Wittig BA (1969) Attachment and exploratory behavior of one-year-olds in a strange situation. In: Foss BM (ed) Determinants of infant behavior, vol 4. Methuen, London, pp 111–136

Albert A, Bulcroft K (1988) Pets, families, and the life course. J Marriage Fam 50:543–552. doi:10.2307/352019

Archer J (1997) Why do people love their pets? Evol Hum Behav 18:237–259. doi:10.1016/S0162-3095(99)80001-4

Archer J, Monton S (2011) Preferences for infant facial features in pet dogs and cats. Ethology 117:217–226. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.2010.01863.x

Askew HR (1996) Treatment of behavior problems in dogs and cats: a guide for the small animal veterinarian. Wiley, London

Berryman JC, Howells K, Lloyd-Evans M (1984) Pet owner attitudes to pets and people: a psychological study. Vet Rec 117:659–661. doi:10.1136/vr.117.25-26.659

Bolinger DL (1964) Around the age of language: Intonation. In: Bolinger D (ed) Intonation. Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, pp 19–29

Bowlby J (1969) Attachement et perte, vol 1: L’attachement. PUF, Paris

Burnham D et al (1998) Are you my little pussy-cat? Acoustic, phonetic and affective qualities of infant-and pet-directed speech. In: Fifth international conference on spoken language processing (ICSLP)

Burnham D, Kitamura C, Vollmer-Conna U (2002) What’s new, pussycat? On talking to babies and animals. Science 296:1435. doi:10.1126/science.1069587

Del Monte Foods, Business Wire (2011) New study reveals that the American family has gone to the dogs. The Milo’s Kitchen™Pet Parent Survey, conducted by Kelton Research. http://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20110502006312/en/Study-Reveals-American-Family-Dogs. Accessed 2 May 2011

Dunst C, Gorman E, Hamby D (2012) Preference for infant-directed speech in preverbal young children. Cent Early Lit Learn Rev 5:1–13

Fernald A (1989) Intonation and communicative intent in mothers’ speech to infants: is the melody the message? Child Dev 60:1497–1510. doi:10.2307/1130938

Fernald A (1992) Meaningful melodies in mothers’ speech to infants. In: Papoušek H, Papoušek M (eds) Nonverbal vocal communication: comparative and developmental approaches. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 262–282

Fernald A, Simon T (1984) Expanded intonation contours in mothers’ speech to newborns. Dev Psychol 20:104–113. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.20.1.104

Fogle B (1992) The dog’s mind: understanding your dog’s behavior. Wiley, New York

Gibson JM, Scavelli SA, Udell CJ, Udell MAR (2014) Domestic dogs (Canis lupus familiaris) are sensitive to the “human” qualities of vocal commands. Anim Behav Cogn 1:281–295. doi:10.12966/abc.08.05.2014

Golinkoff RM, Can DD, Soderstrom M, Hirsh-Pasek K (2015) (Baby) talk to me: the social context of infant-directed speech and its effects on early language acquisition. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 24:339–344. doi:10.1177/0963721415595345

Harrington J, Palethorpe S, Watson CI (2007) Age-related changes in fundamental frequency and formants: a longitudinal study of four speakers. In: Interspeech 2007: 8th annual conference of the international speech communication association, vol 2, pp 1081–1084

Hirsh-Pasek K, Treiman R (1982) Doggerel: Motherese in a new context. J Child Lang 9:229–237. doi:10.1017/S0305000900003731

Horowitz A, Hecht J (2016) Examining dog-human play: the characteristics, affect, and vocalizations of a unique interspecific interaction. Anim Cogn 19:779–788. doi:10.1007/s10071-016-0976-3

Kidd AH, Kidd RM (1989) Factors in adults’ attitudes toward pets. Psychol Rep 65:903–910. doi:10.2466/pr0.1990.66.3.775

Kim H, Diehl MM, Panneton R, Moon C (2006) Hyperarticulation in mothers’ speech to babies and puppies. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the XVth biennial international conference on infant studies, Westin Miyako, Kyoto, Japan. http://citation.allacademic.com/meta/p94616_index.html

Liu HM, Kuhl PK, Tsao FM (2003) An association between mothers’ speech clarity and infants’ speech discrimination skills. Dev Sci 6:F1–F10. doi:10.1111/1467-7687.00275

Marinelli L, Adamelli S, Normando S, Bono G (2007) Quality of life of the pet dog: Influence of owner and dog’s characteristics. Appl Anim Behav Sci 108:143–156. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2006.11.018

Markwell PJ, Thorne CJ (1987) Early behavioural development of dogs. J Small Anim Pract 28:984–991. doi:10.1111/j.1748-5827.1987.tb01322.x

Maxwell SE, Delaney HD (2004) Designing experiments and analyzing data: a model comparison perspective, 2nd edn. Psychology Press, New York

Mitchell RW (2001) Americans’ talk to dogs: similarities and differences with talk to infants. Res Lang Soc Interact 34:183–210. doi:10.1207/S15327973RLSI34-2_2

Mitchell RW (2004) Controlling the dog, pretending to have a conversation, or just being friendly? Influences of sex and familiarity on Americans’ talk to dogs during play. Interact Stud 5:99–129. doi:10.1075/is.5.1.06mit

Mitchell RW, Edmonson E (1999) Functions of repetitive talk to dogs during play: control, conversation, or planning? Soc Anim 7:55–81. doi:10.1163/156853099X00167

Morton ES (1977) On the occurrence and significance of motivation-structural rules in some bird and mammal sounds. Am Nat 111:855–869. doi:10.1086/283219

Nagasawa M, Kikusui T, Onaka T, Ohta M (2009) Dog’s gaze at its owner increases owner’s urinary oxytocin during social interaction. Horm Behav 55:434–441. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.12.002

Nagasawa M, Mitsui S, En S, Ohtani N, Ohta M, Sakuma Y et al (2015) Oxytocin-gaze positive loop and the coevolution of human–dog bonds. Science 348:333–336. doi:10.1126/science.1261022

Newport E, Gleitman H, Gleitman L (1977) Mother, I’d rather do it myself: some effects and non-effects of maternal speech style. In: Snow CE, Ferguson CA (eds) Talking to children. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 109–149

Odendaal JSJ, Meintjes RA (2003) Neurophysiological correlates of affiliative behaviour between humans and dogs. Vet J Lond Engl 165:296–301. doi:10.1016/S1090-0233(02)00237-X

Ohala JJ (1984) An ethological perspective on common cross-language utilization of F0 of voice. Phonetica 41:1–16. doi:10.1159/000261706

Palestrini C, Previde EP, Spiezio C, Verga M (2005) Heart rate and behavioural responses of dogs in the Ainsworth’s Strange Situation: a pilot study. Appl Anim Behav Sci 94:75–88. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2005.02.005

Papoušek M, Bornstein MH, Nuzzo C, Papoušek H, Symmes D (1990) Infant responses to prototypical melodic contours in parental speech. Inf Behav Dev 13:539–545. doi:10.1016/0163-6383(90)90022-Z

Papoušek M, Papoušek H, Symmes D (1991) The meanings of melodies in motherese in tone and stress languages. Infant Behav Dev 14:415–440. doi:10.1016/0163-6383(91)90031-M

Pongrácz P, Miklósi A, Csányi V (2001) Owner’s beliefs on the ability of their pet dogs to understand human verbal communication: a case of social understanding. Curr Psychol Cogn 20:87–107

Poresky RH, Daniels AM (1998) Demographics of pet presence and attachment. Anthrozoös 11:236–241. doi:10.2752/089279398787000508

Prato-Previde E, Custance DM, Spiezio C, Sabatini F (2003) Is the dog-human relationship an attachment bond? An observational study using Ainsworth’s strange situation. Behaviour 140:225–254. doi:10.1163/156853903321671514

Prato-Previde E, Fallani G, Valsecchi P (2006) Gender differences in owners interacting with pet dogs: an observational study. Ethology 112:64–73. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.2006.01123.x

Rehn T, Handlin L, Uvnäs-Moberg K, Keeling LJ (2013) Dogs’ endocrine and behavioural responses at reunion are affected by how the human initiates contact. Physiol Behav 124:45–53. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2013.10.009

Rogers J, Hart LA, Boltz RP (1993) The role of pet dogs in casual conversations of elderly adults. J Soc Psychol 133:265–277. doi:10.1080/00224545.1993.9712145

Saint-Georges C, Chetouani M, Cassel R, Apicella F, Mahdhaoui A, Muratori F et al (2013) Motherese in interaction: at the cross-road of emotion and cognition? (A systematic review). PLoS ONE 8:e78103. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0078103

Siegel S, Castellan NJ (1988) Book review: nonparametric statistics for the behavioral Sciences, 2nd edn. McGraw-Hill, New York

Sokal RR, Rohlf FJ (1995) Biometry: the principals and practice of statistics in biological research, 3rd edn. WH Freman and Company, New York

Sokol RI, Webster KL, Thompson NS, Stevens DA (2005) Whining as mother-directed speech. Infant Child Dev 14:478–490. doi:10.1002/icd.420

Song JY, Demuth K, Morgan JL (2010) Effects of the acoustic properties of infant-directed speech on infant word recognition. J Acoust Soc Am 128:352–363. doi:10.1121/1.3419786

Syrdal A, Kim YJ (2008) Dialog speech acts and prosody: considerations for TTS. In: Proceedings of speech prosody. Campinas, Brazil, pp 661–665

Taylor P (2006) Gauging family intimacy: Pew Research Centers Social Demographic Trends Project RSS. Pew Research Center http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2006/03/07/gauging-family-intimacy/

Thalmann O, Shapiro B, Cui P, Schuenemann VJ, Sawyer SK, Greenfield DL et al (2013) Complete mitochondrial genomes of ancient canids suggest a European origin of domestic dogs. Science 342:871–874. doi:10.1126/science.1243650

Topál J, Miklósi Á, Csányi V, Dóka A (1998) Attachment behavior in dogs (Canis familiaris): a new application of Ainsworth’s (1969) Strange Situation Test. J Comp Psychol 112:219. doi:10.1037/0735-7036.112.3.219

Topál J, Kis A, Oláh K (2014) Dogs’ sensitivity to human ostensive cues: a unique adaptation. In: The social dog. Elsevier, London, pp 319–346

Trainor LJ, Clark ED, Huntley A, Adams BA (1997) The acoustic basis of preferences for infant-directed singing. Infant Behav Dev 20:383–396. doi:10.1016/S0163-6383(97)90009-6

Trainor LJ, Austin CM, Desjardins RN (2000) Is infant-directed speech prosody a result of the vocal expression of emotion? Psychol Sci 11:188–195. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.00240

Xu N, Burnham D, Kitamura C, Vollmer-Conna U (2013) Vowel hyperarticulation in parrot-, dog-and infant-directed speech. Anthrozoos 26:373–380. doi:10.2752/175303713X13697429463592

Acknowledgements

The authors are indebted to David Reby for his invaluable contribution to this article. We would like to thank Dr. S. Perrot (IRCA-ENVA) for providing access to the IRCA room and its facilities at the ENVA. Thanks to Marine Parker, Raphaëlle Bourrec, Raphaëlle Tigeot and Justine Guillaumont for their participation in these experiments, as well as for the pilot experiment. Thanks to Mathieu Amy for help in statistical analyses. Thanks to the CHUVA (ENVA) for help with the recruitment of owners. Thanks to owners who accepted to take part to this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. All applicable international, national and/or institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed and “all procedures performed in studies involving animals were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institution at which the study was conducted”. The study received the approval of the ethical committee of ENVA (COMERC), no. 2015-03-11.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jeannin, S., Gilbert, C. & Leboucher, G. Effect of interaction type on the characteristics of pet-directed speech in female dog owners. Anim Cogn 20, 499–509 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10071-017-1077-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10071-017-1077-7