Abstract

Cryopyrin-associated periodic fever syndrome (CAPS) is a highly debilitating disorder, which is characterized by unregulated interleukin-1β production driven by autosomal dominantly inherited mutations in the NLRP3 gene. Patients with CAPS often present with early-onset episodes of fever and rash. These patients also present with variable systemic signs and symptoms, such as arthritis, sensorineural hearing loss, chronic aseptic meningitis, and skeletal abnormalities, but minimal gastrointestinal symptoms. Recently, effective therapies for CAPS targeted against interleukin-1 have become available. We report a case of a young Japanese woman with CAPS who developed inflammatory bowel disease during canakinumab therapy. The patient had colostomy after intestinal perforation and changed canakinumab to infliximab. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of a case of inflammatory bowel disease secondary to CAPS complicated by gastrointestinal symptoms and arthritis which canakinumab could not control. Patients with CAPS who have symptoms that cannot be controlled by canakinumab should be considered for possible co-morbidities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Cryopyrin-associated periodic fever syndrome (CAPS) is an autosomal dominantly inherited autoinflammatory disorder associated with mutations in the NLRP3 gene, which ultimately lead to excessive production of interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and systemic inflammation. The treatment for CAPS is an anti-IL-1β inhibitor. This is the first report of a case of inflammatory bowel disease secondary to CAPS complicated by gastrointestinal symptoms and arthritis which anti-IL-1β inhibitor could not control.

A female patient showed an urticarial-like rash on the trunk and extremities from early childhood. From approximately 4 years old, arthritis of both knee joints and intermittent fever appeared. She was diagnosed with oligoarticular type juvenile idiopathic arthritis and started taking oral medication of methotrexate and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. After treatment, arthralgia was reduced, but joint swelling and high C-reactive protein (CRP) levels of 6–7 mg/dl (normal < 0.14 mg/dl) persisted. She started taking prednisolone (PSL) for arthralgia and arthritis. After induction of PSL, arthralgia was reduced, but remission was not achieved. PSL was continued at 10 mg/day because a large dose could cause side effects and a small dose could cause more pain. At the age of 15 years, she was suspected of having CAPS due to recurrent fever, an urticarial-like rash, and persistent arthritis. An NLRP3 genetic test was performed. This test showed a mosaic mutation (E567K) and she was diagnosed with CAPS. After introduction of canakinumab, the fever and rash disappeared immediately. We gradually increased the dose of canakinumab (150 → 300 → 450 → 600 mg/dose) and shortened the dosing interval (8 → 6 → 4 weeks), but arthritis and CRP levels did not return to normal.

At the age of 20 years (4 years after canakinumab induction), she underwent gastrointestinal endoscopy for diarrhea of approximately 10 times a day and intermittent fever. A longitudinal ulcer without granuloma was observed. Diagnosis of Epstein–Barr virus enteritis was made because of a small number of Epstein–Barr virus encoded small ribonucleic acid cells, and diarrhea was alleviated by valganciclovir. However, the arthritis persisted and was not dependent on the amount of canakinumab. Therefore, the dose of canakinumab was reduced to 300 mg from 600 mg.

At the ages of 21 and 23 years, she had bloody stool in addition to diarrhea. Gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed multiple longitudinal ulcers (Fig. 1) and a stricture of the terminal ileum (Fig. 2); however, the pathology indicated that “there was atrophic mucosa with erosive inflammation. There was no loss of goblet cells or a disordered or twisted gland duct arrangement. Lymphocytes, plasma cells, and neutrophilic infiltration were found in the lamina propria, and the stroma was edematous. Mild cryptitis was also observed. No epithelioid granuloma had formed and no amyloid was deposited. The above pathological images showed non-specific inflammation. There were no malignant findings and no obvious virus-infected cells”. Therefore, Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis could not be confirmed. Because of intestinal perforation, small bowel stenosis, a high CRP level of 30 mg/dl, and intraperitoneal abscess, fasting management, and antimicrobial therapy were started after colostomy. We considered that the arthritis was attributed to inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), rather than to CAPS, because long-term fasting reduces joint swelling. We changed canakinumab to infliximab to prioritize control of intestinal inflammation, which may cause intestinal perforation and severe arthritis. After switching from canakinumab to infliximab, the arthritis, diarrhea, and quality of life were improved, but an intermittent urticarial-like rash (Fig. 3) emerged with afebrile condition. However, CRP levels remained of approximately 2 mg/dl were observed.

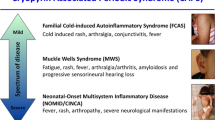

CAPS is a rare inherited autoinflammatory disorder, which is characterized by systemic, cutaneous, musculoskeletal, and central nervous system inflammation. Gain-of-function mutations in NLRP3 in patients with CAPS lead to activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, resulting in inappropriate release of inflammatory cytokines, IL-1β [1, 2]. CAPS includes three clinical entities: familial cold-induced autoinflammatory syndrome, Muckle–Wells syndrome (MWS), and chronic inflammatory neurological cutaneous articular syndrome/neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease. These syndromes share several overlapping clinical features. All of the subtypes have fever, rash, and musculoskeletal, ocular, and central nervous system involvement to varying degrees. Some patients have clinical features that overlap with more than one subtype [3], which is consistent with the concept of a single disease spectrum (Table 1) [4, 5]. To date, there are many different sequence variants of the NLRP3 gene and approximately 100 heterozygous NLRP3 mutations associated with a CAPS phenotype [6,7,8]. The presence of multiple mutations coding the same amino acid suggests mutational hotspots [4]. Our patient with the E567K mutation was considered to have MWS on the basis of clinical symptoms [4].

Because IL-1 plays a central role in the pathogenesis of CAPS, blocking of IL-1 is the main therapeutic approach. Early and aggressive treatment for patients with CAPS is crucial for avoiding end-organ damage. Most CAPS-specific symptoms are reversible if treatment is provided early. Currently, three IL-1 inhibitors, anakinra, rilonacept, and canakinumab, are available. Their safety and effectiveness have been examined and documented in numerous studies [9,10,11,12,13]. Of these, only canakinumab is available in Japan. Canakinumab is a human anti-IL-1β monoclonal antibody that does not react with other members of the IL-1 family. Subcutaneous administration of canakinumab to 35 patients with CAPS resulted in a complete response in 34 patients [10]. Gene mutations of NLRP3 include R260W, T348M, D303N, and E311K [10]. Lachmann et al. showed that treatment with subcutaneous canakinumab once every 8 weeks was associated with a rapid remission of symptoms in most patients with CAPS, especially those with MWS [10]. However, in our female patient with MWS, fever and rash rapidly improved after canakinumab administration, but arthritis did not achieve remission, despite the increase in canakinumab.

Kuemmerle Deschener JB et al. reported that gastrointestinal symptoms such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, and constipation were more common in CAPS patients with low-penetrance NLRP3 variants (Q703K, V198M, and R488K) (73%) than patients with pathogenetic NLRP3 variants (54%) [14]. However, there are no reports of CAPS complicated with IBD regardless of NLRP3 variants as well as E567K pathogenic mutation like this patient.

Specific single-nucleotide polymorphism mutations or polymorphisms related to NLRP3 inflammasome genes contribute to IBD susceptibility in various ways [15]. It has been reported that an aberrant activity of NLRP3 inflammasome in IBD may be due to a specific single-nucleotide polymorphism mutations [16, 17]. However, the role of NLRP3 in IBD is not yet fully elucidated as it seems to demonstrate both pathogenic and protective effects [15]. We could not find any reports of patients with CAPS who had concomitant IBD. In addition, there are no reports that canakinumab induced IBD. Gastrointestinal symptoms not currently included in standard CAPS outcome measures, often resistant to anti-IL-1β therapy, persisted in more than half of the children and adults reassessed at 1-year follow-up [14]. We set a therapeutic goal to reduce intestinal and joint inflammation, rather than fever and rash, for our patient’s quality of life. Although intermittent urticarial-like rash (Fig. 2) and CRP levels of approximately 2 mg/dl continued, we achieved improvement of arthritis and diarrhea by switching from canakinumab to infliximab.

Symptoms vary from mild arthralgia to severe arthritis with painful swelling of joints in approximately 5–10% of patients with ulcerative colitis and in 10–20% of patients with Crohn’s disease. According to available data, most patients with active IBD and concomitant arthritis benefit from infliximab therapy [18]. Infliximab, which is an important treatment for IBD with or without concomitant arthropathy [19], rapidly improves peripheral arthritis in patients with IBD. Some authors reported in open-label studies that there was improvement in peripheral arthritis in patients with IBD who were treated with infliximab at 5 mg/kg; these patients had previously been refractory to PSL or methotrexate [20, 21]. There have been no reports of the effectiveness of infliximab on CAPS. Although there have been several case reports of CAPS [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36], no reports were associated with IBD. We considered that our patient’s arthritis was only caused by IBD-related CAPS or both IBD and CAPS. Even now, the CRP of this patient is around 2 mg/dl; we must be cautious about the onset of amyloidosis in the future. A combination of canakinumab and infliximab may be able to ameliorate all symptoms of IBD secondary to CAPS, but this combination therapy is difficult to recommend in practice because of the rare experience and unpredictable adverse events.

This is the first case of IBD secondary to CAPS complicated by gastrointestinal symptoms and arthritis during canakinumab administration. We intend to follow progress of our patient’s disease carefully.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

References

Stojanov S, Kastner DL (2005) Familial autoinflammatory diseases: genetics, pathogenesis and treatment. Curr Opin Rheumatol 17:586–599

Shinkai K, McCalmont TH, Leslie KS (2008) Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes and autoinflammation. Clin Exp Drmatol 33:1–9

Aksentijevich I, Putnam CD, Remmers EF et al (2007) The clinical continuum of cryopyrinopathies: novel CIAS1 mutations in North American patients and a new cryopyrin model. Arthritis Rheum 56:1273–1285

Booshehri LM, Hoffman HM (2019) CAPS and NLRP3. J Clin Immunol 39:277–286

Kuemmerle-Deschner JB (2015) CAPS – pathogenesis, presentation and treatment of an autoinflammatory disease. Semin Immunopathol 37:377–385

Milhavet F, Cuisset L, Hoffman HM, Slim R, el-Shanti H, Aksentijevich I, Lesage S, Waterham H, Wise C, Sarrauste de Menthiere C, Touitou I (2008) The infevers autoinflammatory mutation online registry: update with new genes and functions. Hum Mutat 29:803–808

Van Gijn ME, Ceccherini I, Shinar Y et al (2018) New workflow for classification of genetic variants’ pathogenicity applied to hereditary recurrent fevers by the International Study Group for Systemic Autoinflammatory Diseases (INSAID). J Med Genet 55:530–537

Touitou I, Lesage S, McDermott M, Cuisset L, Hoffman H, Dode C, Shoham N, Aganna E, Hugot JP, Wise C, Waterham H, Pugnere D, Demaille J, de Menthiere CS (2004) Infevers: an evolving mutation database for autoinflammatory syndromes. Hum Mutat 24:194–198

Hawkins PN, Lachmann HJ, McDermott MF (2003) Interleukin-I-receptor antagonist in the Muckle-Wells syndrome. N Engl J Med 348:2583–2584

Lachmann HJ, Kone-Paut I, Kuemmerle-Deschner JB, Leslie KS, Hachulla E, Quartier P, Gitton X, Widmer A, Patel N, Hawkins PN, Canakinumab in CAPS Study Group (2009) Use of canakinumab in the cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome. N Engl J Med 360:2416–2425

Hoffman HM (2009) Rilonacept for the treatment of cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPS). Expert Opin Biol Ther 9:519–531

Kone-Paut I, Darce-Bello M, Shahram F, Gattorno M, Cimaz R, Ozen S, Cantarini L, Tugal-Tutktun I, Assaad-Khalil S, Hofer M, Kuemmerle-Deschner J, Benamour S, al Mayouf S, Pajot C, Anton J, Faye A, Bono W, Nielsen S, Letierce A, Tran TA, the PED-BD International Expert Committee (2011) Registries in rheumatological and musculoskeletal conditions. Paediatric Behcet’s disease: an international cohort study of 110 patients. One-year follow-up data. Rheumatology (Oxford) 50:184–188

Sibley CH, Plass N, Snow J, Wiggs EA, Brewer CC, King KA, Zalewski C, Kim HJ, Bishop R, Hill S, Paul SM, Kicker P, Phillips Z, Dolan JG, Widemann B, Jayaprakash N, Pucino F, Stone DL, Chapelle D, Snyder C, Butman JA, Wesley R, Goldbach-Mansky R (2012) Sustained response and prevention of damage progression in patients with neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease treated with anakinra: a cohort study to determine three- and five-year outcomes. Arthritis Rheum 64:2375–2386

Kuemmerle Deschner JB, Verma D, Endres T et al (2017) Clinical and molecular phenotypes of low penetrance variants of NLRP3: diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Arthritis Rheum 69:2233–2240

Tourkochristou E, Aggeletopoulou I, Konstantakis C, Triantos C (2019) Role of NLRP3 inflammasome in inflammatory bowel diseases. World J Gastroenterol 25:4796–4804

Villani AC, Lemire M, Fortin G, Louis E, Silverberg MS, Collette C, Baba N, Libioulle C, Belaiche J, Bitton A, Gaudet D, Cohen A, Langelier D, Fortin PR, Wither JE, Sarfati M, Rutgeerts P, Rioux JD, Vermeire S, Hudson TJ, Franchimont D (2009) Common variants in the NLRP3 region contribute to Crohn’s disease susceptibility. Nat Genet 41:71–76

Mao L, Kitani A, Strober W, Fuss IJ (2018) The role of NLRP3 and IL-1β in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Front Immunol 9:2566

Kujundzic M (2013) The role of biologic therapy in the treatment of extraintestinal manifestations and complications of inflammatory bowel disease. Acta Med Croatica 67:195–201

Barrie A, Regueiro M (2007) Biologic therapy in the management of extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowl Dis 13:1424–1429

Kaufman I, Caspi D, Yeshurun D, Dotan I, Yaron M, Elkayam O (2005) The effect of infliximab on extraintestinal manifestations of Crohn’s disease. Rheumatol Int 25:406–410

Ellman M, Hanauer S, Sitrin M, Cohen R (2001) Crohn’s disease arthritis treated with infliximab: an open trial in four patients. J Clin Rheumatol 7:67–71

Fingerhutova S, Franova J, Hlavackova E et al (2019) Muckle-Wells syndrome across four generations in one Czech family: natural course of the disease. Front Immunol 10:802

Lasiglie D, Mensa VA, Ferrera D et al (2017) Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome in Italian patients: evaluation of the rate of somatic NLRP3 mosaicism and phenotypic characterization. J Rheumatol 44:1667–1673

Abdulla MC, Alungal J, Hawkins PN, Mohammed S (2015) Muckle-Wells syndrome in an Indian family associated with NLRP3 mutation. J Postgrad Med 61:120–122

Caorsi R, Lepore L, Zulian F, Alessio M, Stabile A, Insalaco A, Finetti M, Battagliese A, Martini G, Bibalo C, Martini A, Gattorno M (2013) The schedule of administration of canakinumab in cryopyrin associated periodic syndrome is driven by the phenotype severity rather than the age. Arthritis Res Ther 15:R33

Aoyama K, Amano H, Takaoka Y, Nishikomori R, Ishikawa O (2012) Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome: a case report and review of the Japanese literature. Acta Derm Venereol 92:395–398

Kilic H, Sahin S, Duman C, Adrovic A, Barut K, Turanli ET, Yildirim SR, Kizilkilic O, Kasapcopur O, Saltik S (2019) Spectrum of the neurologic manifestations in childhood-onset cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 23:466–472

Houx L, Hachulla E, Kone-Paut I, Quartier P, Touitou I, Guennoc X, Grateau G, Hamidou M, Neven B, Berthelot JM, Lequerré T, Pillet P, Lemelle I, Fischbach M, Duquesne A, le Blay P, le Jeunne C, Stirnemann J, Bonnet C, Gaillard D, Alix L, Touraine R, Garcier F, Bedane C, Jurquet AL, Duffau P, Smail A, Frances C, Grall-Lerosey M, Cathebras P, Tran TA, Morell-Dubois S, Pagnier A, Richez C, Cuisset L, Devauchelle-Pensec V (2015) Musculoskeletal symptoms in patients with cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes: a large database study. Arthritis Rheumatol 67:3027–3036

Marchica C, Zawawi F, Basodan D, Scuccimarri R, Daniel SJ (2018) Resolution of unilateral sensorineural hearing loss in a pediatric patient with a severe phenotype of Muckle-Wells syndrome treated with Anakinra: a case report and review of the literature. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 47:9

Mehr S, Allen R, Boros C, Adib N, Kakakios A, Turner PJ, Rogers M, Zurynski Y, Singh-Grewal D (2016) Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome in Australian children and adults: epidemiological, clinical and treatment characteristics. J Paediatr Child Health 52:889–895

Naz Villalba E, Gomez de la Fuente E, Caro Gutierrez D, Pinedo Moraleda F, Yanguela Rodilla J, Mazagatos Angulo D, López Estebaranz JL (2016) Muckle-Wells syndrome: a case report with an NLRP3 T348M mutation. Pediatr Dermatol 33:e311–e314

Posch C, Kaulfersch W, Rappersberger K (2014) Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol 31:228–231

Ramos E, Arostegui JI, Campuzano S, Rius J, Bousono C, Yague J (2005) Positive clinical and biochemical responses to anakinra in a 3-yr-old patient with cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome (CAPS). Rheumatology (Oxford) 44:1072–1073

Eskola V, Pohjankoski H, Kroger L, Aalto K, Latva K, Korppi M (2018) Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome in early childhood can be successfully treated with interleukin-I blockades. Acta Paediatr 107:577–580

Iida Y, Wakiguchi H, Okazaki F, Nakamura T, Yasudo H, Kubo M, Sugahara K, Yamashita H, Suehiro Y, Okayama N, Hashimoto K, Iwamoto N, Kawakami A, Aoki Y, Takada H, Ohga S, Hasegawa S (2019) Early canakinumab therapy for the sensorineural deafness in a family with Muckle-Wells syndrome due to a novel mutation of NLRP3 gene. Clin Rheumatol 38:943–948

Lainka E, Neudorf U, Lohse P, Timmann C, Bielak M, Stojanov S, Huss K, Kries R, Niehues T (2010) Analysis of cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPS) in German children: epidemiological, clinical and genetic characteristics. Klin Padiatr 222:356–361

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Yuga Komaki (Department of Digestive and Lifestyle diseases, Kagoshima University Hospital) for performing intestinal endoscopy. We thank Ellen Knapp, PhD, from Edanz Group (www.edanzediting.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and all authors approved the final version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

None.

Ethics approval

All ethical considerations are taken into account to protect patient rights.

Consent to participate and consent for publication

We obtained consent from this patient for report and publication.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yamasaki, Y., Kubota, T., Takei, S. et al. A case of cryopyrin-associated periodic fever syndrome during canakinumab administration complicated by inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Rheumatol 40, 393–397 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-020-05267-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-020-05267-1