Abstract

Introduction

Clinical guidelines have recommended a target of serum uric acid (SUA) level below 6.0 mg/dL for the urate-lowering therapy (ULT) of gout patients, but there are still a high proportion of patients failing to achieve the therapeutic target above. This study aimed to identify possible predictors of poor response to ULT in gout patients.

Methods

We performed a post-hoc analysis of a multicenter randomized double-blind trial which assessed the efficacy of febuxostat in patients with hyperuricemia (serum urate level ≥ 8.0 mg/dL) and gout. Demographic characters and baseline data including SUA levels were collected. Poor response to ULT was defined as average SUA after ULT was more than 6.0 mg/dL. Factors associated with poor response to ULT in gout patients were analyzed, and multivariate logistic regression analysis was also carried out to find out those independent predictors.

Results

A total of 370 patients were enrolled in this post-hoc analysis. Compared with those with good response to ULT, patients with poor response to ULT had younger age (P < 0.001), higher proportion of obesity (P = 0.003), higher proportion of statins use (P = 0.019), higher body mass index (BMI) (P < 0.001), higher baseline SUA (P < 0.001), higher proportion of males (P = 0.001), higher alanine transaminase (P < 0.001), higher aspartate transaminase (P = 0.017), higher total cholesterol (P = 0.005), higher triglyceride (P = 0.042), and higher low density lipoprotein (P = 0.037). Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that younger age (odds ratio (OR) = 0.965, 95% CI 0.943–0.987, P = 0.002), higher BMI (OR = 1.133, 95% CI 1.049–1.224, P = 0.001), higher baseline SUA (OR = 1.006, 95% CI 1.002–1.009, P = 0.001), and no application of febuxostat therapy (OR = 0.41, 95% CI 0.25–0.68, P < 0.001) were independent predictors of poor response to ULT in patients with gout.

Conclusion

In patients with gout and hyperuricemia, younger age, higher BMI, and higher baseline SUA are predictors of poor response to ULT. These findings could help physicians better identify patients who may fail in ULT and give individualized treatment precisely.

Trial registration

The trial was registered at chinadrugtrials.org.cn in 2012 (CTR20130172).

Key Points • A post-hoc analysis of a multicenter randomized double-blind trial which assessed the efficacy of febuxostat in patients with hyperuricemia and gout was performed. • Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that younger age, higher BMI, and higher baseline SUA are predictors of poor response to urate-lowering therapy. |

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Gout is a disorder caused by deposition of monosodium urate in bone joints and other tissues as a result of the supersaturation of extracellular uric acid [1, 2]. Its prevalence is increasing significantly worldwide which may be related to increased frequency of obesity, hypertension, metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), chronic kidney disease, and so on [2,3,4]. Findings based on the latest nationally representative sample of the USA revealed that the prevalence of gout among US adults in 2007–2008 was up to 3.9% [5], and the annual hospitalization rate for gout increased from 4.4 to 8.8 per 100,000 US adults from 1993 to 2011 [6]. In China, about 1–3% of people suffer from gout and the number is still growing year by year [7]. The natural course of gout goes through asymptomatic hyperuricemia, acute gouty flares, and chronic polyarticular gout; and its manifestations include tophi, gouty nephropathy, and kidney stones [8]. High serum uric acid (SUA) level can accelerate the progression from asymptomatic hyperuricemia to advanced gout, and can also result in increased risk of comorbidities and worse prognosis [1, 9, 10].

When treating gout, excessive uric acid storage should be reduced by long-term reduction of SUA concentration with its level well below the threshold for urate saturation to achieve dissolution of monosodium urate crystals and prevent gouty flares [11]. Xanthine oxidase inhibitors including allopurinol and febuxostat are recommended as the first-line agents for urate-lowering therapy (ULT) in gout patients [2]. For gout patients with ULT, a target SUA level below 6.0 mg/dL was recommended by both American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) [2, 12]. However, approximately more than 50% of the patients could not meet treatment target after a long period of ULT [13, 14]. In China, only about 30% gout patients had achieved the treatment target [15]. Therefore, it’s critical to identify some predictors of poor response to ULT in gout patients, which may help physicians better identify patients who may fail in ULT and modify the ULT dosage to increase treatment response [16]. The aim of this study was to find predictors of poor response to ULT in Chinese patients with gout, so as to predict treatment outcomes precisely and provide individualized treatment suggestions.

Methods

Study design and population

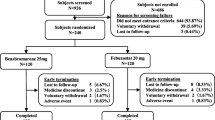

Data from a multicenter randomized double-blind trial were used in our study, which was performed to assess the efficacy of febuxostat in patients with hyperuricemia (serum urate level ≥ 8.0 mg/dL) and gout. The trial was conducted at 8 hospitals in China and had a duration of 24 weeks and was registered at chinadrugtrials.org.cn (CTR20130172). This clinical trial conformed to principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the Good Clinical Practice of China. All participants were voluntary and signed the written consent prior to any research procedure. Eligible participants were at the age of 18–70 with any sex. All patients were diagnosed with primary gout according to the criteria developed by the ACR/EULAR with SUA level of at least 8.0 mg/dL [17]. Patients experienced a 2-week washout time. During this period, subjects who were receiving ULT were asked to stop it. There was no acute gouty flare during the washout period and 2 weeks before it. Exclusion criteria included hepatic dysfunction with alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) exceed 1.5 times of the upper limit of normal range; impaired renal function with serum creatinine (Cr) above the reference range; serious heart disease such as unstable angina pectoris; pregnancy; any other physical problems which may affect the efficacy of ULT. According to the drug dosage recommended in the Chinese Expert Consensus on Hyperuricemia and Gout Treatment [18], 466 subjects enrolled into the study were randomized to receive febuxostat 40 mg (n = 154) or 80 mg (n = 156) once per day or allopurinol 100 mg three times per day (n = 156) for 24 weeks. Low-calorie and low-purine diet were required in order to achieve the target. Data from 96 patients were unable to be included in this post-hoc analysis, because they withdrew from trial, were lost to follow-up, had protocol deviations or had adverse events. Therefore, 370 patients were finally included into this post-hoc analysis (Fig. 1).

Patient profile data and outcome definition

Patient profile data, such as demographic characteristics and clinical characteristics, were collected by the original investigators. SUA levels were measured at baseline, 2 weeks and 4 weeks after ULT treatment, and were then measured every 4 weeks until 24 weeks after ULT treatment. Poor response to ULT treatment was defined as the average SUA after ULT was more than 6.0 mg/dL (360 μmol/L).

Statistical analysis

Continuous data were described in mean ± standard deviation (SD) and were analyzed by Student’s t test. Categorical data were described in number and percentages and were compared using the chi-squared test. To preliminarily identify factors associated with poor response to ULT in gout patients, difference in the demographic characteristics and clinical characteristics between gout patients with or without poor response to ULT were compared. Logistic regression analysis was then performed to find out those predictors of poor response to ULT. Variables in the univariate analysis with P < 0.10 entered the multivariate analysis, and confounding factors in the multivariate analysis included age, gender, hyperlipidemia, obesity, statins use, baseline SUA, diastolic blood pressure (DBP), ALT, AST, triglyceride (TG), total cholesterol (TC), low density lipoprotein (LDL), and febuxostat therapy. According to the results of univariate analysis, multivariate analysis was finally carried out to find out those independent predictors for poor response to ULT therapy. All data were processed by STATA (version 12.0). P value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of gout patients

Among those 370 subjects, 128 received febuxostat 80 mg once per day, 112 received febuxostat 40 mg once per day, and 130 received allopurinol 100 mg three times per day (Table 1). The mean baseline SUA levels for those three groups were 587.7, 580.5, and 577.1 μmol/L respectively, and no obvious difference was observed among those three groups (P = 0.55) (Table 1). There was no statistically significant difference in other profile data except for fasting blood glucose (FBG), LDL cholesterol, and if they had T2DM (Table 1).

Clinical and biological features by response to ULT

Among the 370 patients, 186 reached the therapeutic target of SUA level of less than 6.0 mg/dL while the other 184 had poor response to ULT. The difference in the clinical and biological features by response to ULT was shown in Table 2. There was difference in the percentages of ULT treatment, and patients with poor response to ULT had higher proportion of allopurinol therapy and lower proportion of febuxostat therapy (P < 0.001, Table 2). There was no significant difference in if they had T2DM or hypertension. The differences in systolic blood pressure (SBP), DBP, total bilirubin (TBIL), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), Cr, and FBG between two groups were not significant. The average age of the subjects with poor response to ULT was younger (49.9 vs 43.5 years, P < 0.001). The proportion of male patients (89.2 vs 97.8%, P = 0.001) and obesity patients (30.1 vs 45.1%, P = 0.003) in the poor-response group was higher. The proportion of patients who had hyperlipidemia (15.1 vs 6.5%, P = 0.008) or patients with statins use (4.3% vs 0.5%, P = 0.019) was higher in adequate control group. Patients in poor response group were more likely to have higher body mass index (BMI) (26.3 vs 27.6 kg/m2, P < 0.001), baseline SUA (559.6 vs 604.3 μmol/L, P < 0.001), ALT (26.9 vs 35.4 U/L, P < 0.001), AST (23.2 vs 26.1 U/L, P = 0.017), TG (2.4 vs 2.8 mmol/L, P = 0.042), TC (5.0 vs 5.3 mmol/L, P = 0.005), as well as LDL (2.9 vs 3.1 mmol/L, P = 0.037) (Table 2). The incidence rate of acute gout attacks at different follow-up times and adverse drug reactions were showed in Supplementary Table 1 and 2.

Independent predictors of poor response to ULT

The outcomes of logistic regression analysis were shown in Table 3. Younger age (odds ratio (OR) = 0.965, 95% CI 0.943–0.987, P = 0.002), higher BMI (OR = 1.133, 95% CI 1.049–1.224, P = 0.001), higher baseline SUA level (OR = 1.006, 95% CI 1.002–1.009, P = 0.001) and no application of febuxostat therapy (OR = 0.41, 95% CI 0.25–0.68, P < 0.001) were independently associated with poor response to ULT in patients with gout and hyperuricemia. Unexpectedly, hyperlipidemia was related to lower risk of poor response to ULT (P = 0.033).

Discussion

This post-hoc analysis explored predictors of poor response to ULT in patients with gout and hyperuricemia. To our knowledge, it is the first study which used data from a randomized trial to explore predictors of poor response to ULT in patients with gout and hyperuricemia. The results indicated that younger age, higher BMI, higher SUA, at baseline and no application of febuxostat therapy were independently related to poor response to ULT in patients with gout and hyperuricemia.

There were several previous studies on factors influencing the efficacy of ULT in patients with gout, but the results varied from different researches. In a retrospective cohort study containing 678 subjects, Sheer et al. followed the patients for 365 days [19]. Similar to our findings, the results suggested that for gout patients received febuxostat, lower baseline SUA level was the significant predictor of achieving a SUA goal < 6.0 mg/dL [19]. In another study including 18,456 gout patients in which the follow-up lasted for 6 months, logistic regression analysis showed that patients with higher baseline SUA levels were less likely to reach the SUA goal [20]. Another study by Fei et al. pointed out that baseline SUA had no impact on the prognosis of ULT, which might be biased due to its small sample size (n = 72) [21].

It has been revealed that higher BMI is closely related to hyperuricemia, and successful weight management is associated with significant urate reduction [22, 23]. Compared with other tissues, xanthine oxidase, which is crucial for the production of uric acid, is proved to be highly expressed in adipose tissue. In obese state, enzyme activity of xanthine oxidase and its product uric acid are all increased [24]. Thus, xanthine oxidase in adipocytes may play an important role in hyperuricemia for obese patients. In line with the previous studies, our results revealed that patients with higher BMI were less likely to achieve ULT goals, which further outlined the important influence of obesity in the development of gout and hyperuricemia.

The findings in our study supported that younger age was an independent predictor of poor response to ULT in patients with gout and hyperuricemia. One possible explanation for the finding above is the adherence to ULT in older patients. A systematic review focusing on the medication adherence to ULT among gout patients revealed that the proportion of non-adherent patients ranged from 54% to 87% [25]. Previous studies had found that high adherence to ULT medicines was the predictor of reaching the SUA goal [19, 26], and suboptimal medication compliance could reduce the effectiveness of ULT [27]. Several studies had demonstrated that increased age was associated with increased adherence, and older patients were more persistent with ULT and they were more likely to reach the goal level [20, 28,29,30,31]. Therefore, the higher adherence to ULT in older patients may explain why patients with younger age are less likely to achieve urate lowering goals.

Our study found that male gender was related to poor response to ULT in patients with gout and hyperuricemia in the univariate analysis, but it was not statistically significant in multivariate analysis (Table 3). Morlock et al. demonstrated that female gender was one of the predictors of gout control [26]. In Hatoum’s study, the results also showed that women patients were more likely to reach SUA goal level [20]. The non-significant in our study was more likely to be caused by the relatively low statistical power from one single study. More future studies are warranted to assess whether gender is independently relevant to the outcome of ULT in gout patients.

Large clinical trials have showed that compared with allopurinol, febuxostat was more effective at lowering SUA level [14, 32]. The proportion of patients who reached the SUA target at the end of the trials was significantly higher in febuxostat group than that in allopurinol group [14, 32]. Interestingly, those who switched to febuxostat from allopurinol had significantly higher likelihood of attaining SUA goal of lower than 6.0 mg/dL and 5.0 mg/dL compared with the patients who maintained on allopurinol [20, 33]. However, factors affecting the prognosis of ULT were not analyzed in those experiments. In accordance with previous researches, no application of febuxostat therapy was demonstrated to be one important predictor of poor response to ULT in this study. Febuxostat is a selective xanthine oxidase inhibitor, while allopurinol has effects on other enzymes involved in uric acid metabolism which may be associated with its side effects [34]. Therefore, febuxostat might be a promising alternative to allopurinol for the treatment of hyperuricemia and gout. However, febuxostat is not superior to allopurinol in all respects. One recent clinical trial concerning the cardiovascular safety of febuxostat and allopurinol showed that compared with allopurinol group, all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality were significantly higher in febuxostat group [35]. Therefore, different urate-lowering medicines should be chosen according to patients’ different conditions.

The findings in our study indicated that hyperlipidemia was an independent predictor of lower risk of poor response to ULT. Previous studies have found that cholesterol-lowering therapy with a statin could significantly lower serum uric acid levels in patients treated for primary hyperlipidemia or other diseases [36, 37]. It seemed to be the reason why hyperlipidemia was related to lower risk of poor response to ULT. However, the results of multivariate analysis showed that statins use was not statistically significant. It has been pointed out that not all kinds of statins have urate lowering effect. A meta-analysis evaluating the effect size of statins in modulating plasma uric acid concentrations showed that atorvastatin and simvastatin can reduce serum uric acid levels while pravastatin and rosuvastatin cannot [36]. The non-significant in the analysis was likely to be caused by differences in statins used by different patients. Moreover, the limited number of subjects using statins might also lead to the non-significant result. Studies with large sample size are needed in the future to further evaluate the effect of statins on patients with hyperuricemia and gout.

Based on the results above as well as the results of previous studies, for patients who may have poor response to ULT, special emphasis should be placed on patient education of diet and lifestyle first and foremost. Besides, other medicines such as uricosuric agent benzbromarone or probenecid could be prescribed in priority or added to the xanthine oxidase inhibitor in order to obtain an optimal treatment outcome. What’s more, treatment of concomitant diseases or surgery should be provided in time whenever needed.

This study had several limitations. First, the number of subjects was not large enough, and only Chinese patients were enrolled in the study which may result in limited generalizability. Second, medicines used for ULT only included febuxostat and allopurinol. Whether other ULT medicines such as benzbromarone had impact on the outcome of ULT was not clear. Third, definite criteria for the evaluation of patient compliance were not established which may be related to the result of ULT. What’s more, factors affecting the prognosis of ULT therapy in patients with specific diseases with regard to particular endpoints were not assessed in our study. Therefore, well-designed long-term clinical trials with adequate sample size concerning specific diseases and endpoints are needed to explore the predictors of ULT failure further.

In summary, the study suggests that younger age, higher BMI and higher baseline SUA are predictors of poor response to ULT in patients with gout and hyperuricemia. Since early detection of patients with high probability of ULT failure may help physicians to give professional advice timely and enable precise treatment strategy, the finding in our study represents a step towards personalized treatment for gout patients. Additionally, the findings from our study warrant further validation from more prospective and adequately powered studies.

Abbreviations

- ACR:

-

American College of Rheumatology

- ALT:

-

Alanine aminotransferase

- AST:

-

Aspartate aminotransferase

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- BUN:

-

Blood urea nitrogen

- Cr:

-

Creatinine

- DBP:

-

Diastolic blood pressure

- EULAR:

-

European League Against Rheumatism

- FBG:

-

Fasting blood glucose

- LDL:

-

Low density lipoprotein

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- SBP:

-

Systolic blood pressure

- SUA:

-

Serum uric acid

- T2DM:

-

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

- TBIL:

-

Total bilirubin

- TC:

-

Total cholesterol

- TG:

-

Triglyceride

- ULT:

-

Urate-lowering therapy

References

Dalbeth N, Merriman TR, Stamp LK (2016) Gout. Lancet 388(10055):2039–2052. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00346-9

Khanna D, Fitzgerald JD, Khanna PP, Bae S, Singh MK, Neogi T, Pillinger MH, Merill J, Lee S, Prakash S, Kaldas M, Gogia M, Perez-Ruiz F, Taylor W, Liote F, Choi H, Singh JA, Dalbeth N, Kaplan S, Niyyar V, Jones D, Yarows SA, Roessler B, Kerr G, King C, Levy G, Furst DE, Edwards NL, Mandell B, Schumacher HR, Robbins M, Wenger N, Terkeltaub R, American College of R (2012) 2012 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. Part 1: systematic nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapeutic approaches to hyperuricemia. Arthritis Care Res 64(10):1431–1446. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.21772

Elfishawi MM, Zleik N, Kvrgic Z, Michet CJ Jr, Crowson CS, Matteson EL, Bongartz T (2018) The rising incidence of gout and the increasing burden of comorbidities: a population-based study over 20 years. J Rheumatol 45(4):574–579. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.170806

Zobbe K, Prieto-Alhambra D, Cordtz R, Hojgaard P, Hindrup JS, Kristensen LE, Dreyer L (2018) Secular trends in the incidence and prevalence of gout in Denmark from 1995 to 2015: a nationwide register-based study. Rheumatology. 58:836–839. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/key390

Zhu Y, Pandya BJ, Choi HK (2011) Prevalence of gout and hyperuricemia in the US general population: the national health and nutrition examination survey 2007-2008. Arthritis Rheum 63(10):3136–3141. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.30520

Lim SY, Lu N, Oza A, Fisher M, Rai SK, Menendez ME, Choi HK (2016) Trends in gout and rheumatoid arthritis hospitalizations in the United States, 1993-2011. Jama 315(21):2345–2347. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.3517

Xiaofeng Z, Yaolong C (2017) 2016 China guidelines for management of gout. Chin J Intern Med 55(11):892–899. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1426.2016.11.019

Roddy E, Mallen CD, Doherty M (2013) Gout. BMJ 347:f5648. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f5648

Wood R, Fermer S, Ramachandran S, Baumgartner S, Morlock R (2016) Patients with gout treated with conventional urate-lowering therapy: association with disease control, health-related quality of life, and work productivity. J Rheumatol 43(10):1897–1903. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.151199

Shiozawa A, Buysman EK, Korrer S (2017) Serum uric acid levels and the risk of flares among gout patients in a US managed care setting. Curr Med Res Opin 33(1):117–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007995.2016.1239193

Schlesinger N, Dalbeth N, Perez-Ruiz F (2009) Gout–what are the treatment options? Expert Opin Pharmacother 10(8):1319–1328. https://doi.org/10.1517/14656560902950742

Richette P, Doherty M, Pascual E, Barskova V, Becce F, Castaneda-Sanabria J, Coyfish M, Guillo S, Jansen TL, Janssens H, Liote F, Mallen C, Nuki G, Perez-Ruiz F, Pimentao J, Punzi L, Pywell T, So A, Tausche AK, Uhlig T, Zavada J, Zhang W, Tubach F, Bardin T (2017) 2016 updated EULAR evidence-based recommendations for the management of gout. Ann Rheum Dis 76(1):29–42. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209707

Juraschek SP, Kovell LC, Miller ER 3rd, Gelber AC (2015) Gout, urate-lowering therapy, and uric acid levels among adults in the United States. Arthritis Care Res 67(4):588–592. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.22469

Schumacher HR Jr, Becker MA, Wortmann RL, Macdonald PA, Hunt B, Streit J, Lademacher C, Joseph-Ridge N (2008) Effects of febuxostat versus allopurinol and placebo in reducing serum urate in subjects with hyperuricemia and gout: a 28-week, phase III, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group trial. Arthritis Rheum 59(11):1540–1548. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.24209

Luo H, Fang WG, Zuo XX, Wu R, Li XX, Chen JW, Zhou JG, Yang J, Song H, Duan XJ, Lin XF, Zeng XW, Zeng H (2018) The clinical characteristics, diagnosis and treatment of patients with gout in China. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi 57(1):27–31. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1426.2018.01.005

Graham GG, Stocker SL, Kannangara DRW, Day RO (2018) Predicting response or non-response to urate-lowering therapy in patients with gout. Curr Rheumatol Rep 20(8):47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11926-018-0760-2

Neogi T, Jansen TL, Dalbeth N, Fransen J, Schumacher HR, Berendsen D, Brown M, Choi H, Edwards NL, Janssens HJ, Liote F, Naden RP, Nuki G, Ogdie A, Perez-Ruiz F, Saag K, Singh JA, Sundy JS, Tausche AK, Vaquez-Mellado J, Yarows SA, Taylor WJ (2015) 2015 Gout classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis 74(10):1789–1798. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208237

Endocrinology CSo (2013) Chinese expert consensus on hyperuricemia and gout treatment. Chin J Endocrinol Metab 29(11):913–920

Sheer R, Null KD, Szymanski KA, Sudharshan L, Banovic J, Pasquale MK (2017) Predictors of reaching a serum uric acid goal in patients with gout and treated with febuxostat. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res 9:629–639. https://doi.org/10.2147/CEOR.S139939

Hatoum H, Khanna D, Lin SJ, Akhras KS, Shiozawa A, Khanna P (2014) Achieving serum urate goal: a comparative effectiveness study between allopurinol and febuxostat. Postgrad Med 126(2):65–75. https://doi.org/10.3810/pgm.2014.03.2741

Fei Y, Cong Y, Wei T, Guifeng S, Linli D, Shaoxian H, Yikai Y, Ting Y (2017) Analysis of factors influencing the therapeutic effect of lowering uric acid in patients with gout. Chin J Rheumatol 21(2):110–113

Choi HK, Atkinson K, Karlson EW, Curhan G (2005) Obesity, weight change, hypertension, diuretic use, and risk of gout in men: the health professionals follow-up study. Arch Intern Med 165(7):742–748. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.165.7.742

Zhou J, Wang Y, Lian F, Chen D, Qiu Q, Xu H, Liang L, Yang X (2017) Physical exercises and weight loss in obese patients help to improve uric acid. Oncotarget 8(55):94893–94899. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.22046

Cheung KJ, Tzameli I, Pissios P, Rovira I, Gavrilova O, Ohtsubo T, Chen Z, Finkel T, Flier JS, Friedman JM (2007) Xanthine oxidoreductase is a regulator of adipogenesis and PPARgamma activity. Cell Metab 5(2):115–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2007.01.005

Scheepers L, van Onna M, Stehouwer CDA, Singh JA, Arts ICW, Boonen A (2018) Medication adherence among patients with gout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 47(5):689–702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2017.09.007

Morlock R, Chevalier P, Horne L, Nuevo J, Storgard C, Aiyer L, Hines DM, Ansolabehere X, Nyberg F (2016) Disease control, health resource use, healthcare costs, and predictors in gout patients in the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, and France: a retrospective analysis. Rheumatol Ther 3(1):53–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-016-0033-3

Winckler K, Obe G, Madle S, Kocher-Becker U, Kocher W, Nau H (1987) Cyclophosphamide: interstrain differences in the production of mutagenic metabolites by S9-fractions from liver and kidney in different mutagenicity test systems in vitro and in the teratogenic response in vivo between CBA and C 57 BL mice. Teratog Carcinog Mutagen 7(4):399–409

Harrold LR, Andrade SE, Briesacher BA, Raebel MA, Fouayzi H, Yood RA, Ockene IS (2009) Adherence with urate-lowering therapies for the treatment of gout. Arthritis Res Ther 11(2):R46. https://doi.org/10.1186/ar2659

Riedel AA, Nelson M, Joseph-Ridge N, Wallace K, MacDonald P, Becker M (2004) Compliance with allopurinol therapy among managed care enrollees with gout: a retrospective analysis of administrative claims. J Rheumatol 31(8):1575–1581

Janssen CA, Oude Voshaar MAH, Vonkeman HE, Krol M, van de Laar M (2018) A retrospective analysis of medication prescription records for determining the levels of compliance and persistence to urate-lowering therapy for the treatment of gout and hyperuricemia in the Netherlands. Clin Rheumatol 37(8):2291–2296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-018-4127-x

McGowan B, Bennett K, Silke C, Whelan B (2016) Adherence and persistence to urate-lowering therapies in the Irish setting. Clin Rheumatol 35(3):715–721. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-014-2823-8

Becker MA, Schumacher HR Jr, Wortmann RL, MacDonald PA, Eustace D, Palo WA, Streit J, Joseph-Ridge N (2005) Febuxostat compared with allopurinol in patients with hyperuricemia and gout. N Engl J Med 353(23):2450–2461. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa050373

Altan A, Shiozawa A, Bancroft T, Singh JA (2015) A real-world study of switching from allopurinol to febuxostat in a health plan database. J Clin Rheumatol 21(8):411–418. https://doi.org/10.1097/RHU.0000000000000322

Takano Y, Hase-Aoki K, Horiuchi H, Zhao L, Kasahara Y, Kondo S, Becker MA (2005) Selectivity of febuxostat, a novel non-purine inhibitor of xanthine oxidase/xanthine dehydrogenase. Life Sci 76(16):1835–1847. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2004.10.031

White WB, Saag KG, Becker MA, Borer JS, Gorelick PB, Whelton A, Hunt B, Castillo M, Gunawardhana L, Investigators C (2018) Cardiovascular safety of febuxostat or allopurinol in patients with gout. N Engl J Med 378(13):1200–1210. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1710895

Derosa G, Maffioli P, Reiner Z, Simental-Mendia LE, Sahebkar A (2016) Impact of statin therapy on plasma uric acid concentrations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drugs 76(9):947–956. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-016-0591-2

Milionis HJ, Kakafika AI, Tsouli SG, Athyros VG, Bairaktari ET, Seferiadis KI, Elisaf MS (2004) Effects of statin treatment on uric acid homeostasis in patients with primary hyperlipidemia. Am Heart J 148(4):635–640. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2004.04.005

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Robin Wang for advice regarding statistical analysis of data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design, data collection, analysis of the data, interpretation of the results, and drafting of the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

None.

Ethical standards

This clinical trial conformed to principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the Good Clinical Practice of China and was approved by the Drug Clinical Trial Ethics Committee, Shandong Provincial Hospital. All participants provided written informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(XLSX 12 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mu, Z., Wang, W., Wang, J. et al. Predictors of poor response to urate-lowering therapy in patients with gout and hyperuricemia: a post-hoc analysis of a multicenter randomized trial. Clin Rheumatol 38, 3511–3519 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-019-04737-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-019-04737-5