Abstract

Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS), caused by mutations in the TNFRSF1A gene, is the most frequent autosomal dominant autonflammatory disease displaying a relevant risk of reactive AA amyloidosis, if left untreated. Our report deals with one adult with TRAPS complicated by amyloidosis-related renal failure, treated with the recombinant human interleukin-1 receptor antagonist anakinra at a higher than conventional dosage. This treatment did not present any adverse event and led remarkably to the disappearance of all TRAPS-related manifestations and prompt decrease of laboratory abnormalities, including proteinuria. A review of the medical literature has been also considered to evaluate efficacy and safety of interleukin-1 inhibition in patients with TRAPS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS), caused by mutations in the TNFRSF1A gene, is the most frequent autosomal dominant autoinflammatory disease [1]. Commonly, TRAPS starts with recurrent episodes of high fevers occurring every 5–6 weeks, generally lasting up to 3 weeks, associated with protean manifestations including muscle cramps, skin signs, periorbital edema, arthritis, abdominal, and/or chest pain [2,3,4,5,6,7]. Treating TRAPS is usually more challenging than other autoinflammatory disorders, due to its highly variable clinical spectrum. Primary target of treatment should be represented by the control of clinical manifestations and laboratory abnormalities, improvement of patients’ quality of life, and prevention of long-term complications, first of all, reactive AA amyloidosis [8]. Currently, interleukin (IL)-1 inhibition represents the mainstay of therapy for TRAPS patients [9]. However, although a reduced drug clearance may theoretically increase the probability for adverse events in patients with impaired kidney function, to the best of our knowledge, no data are available about the use of IL-1 inhibitors in TRAPS patients with amyloidosis-related renal failure. Therefore, we herein present one TRAPS patient with systemic amyloidosis and severe renal impairment who was treated with the recombinant human IL-1 receptor antagonist anakinra (ANA).

Case report

A 59-year-old Caucasian woman came to our attention for a history of recurrent fever, arthralgia, severe myalgia in lower limbs, migratory erythematosus rashes, and abdominal pain since she was 2. During adult life, symptoms had become milder, with a chronic course and persistence of widespread muscle pains and occasional low-grade fevers. At 58 years, severe proteinuria in the nephrotic range (25–18 g/day) was documented after the onset of perimalleolar edema. Additional laboratory assessment showed increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR, 112 mm/h), C-reactive protein (CRP, 4.4 mg/dl), serum amyloid-A (SAA, 173.4 mg/l), blood urea nitrogen (40 mg/dl), serum creatinine (2.52 mg/dl), serum proteins (5.4 g/dl), and glomerular filtration rate (GFR, 14.58 ml/min). Moreover, full laboratory and instrumental screening tests ruled out infectious, neoplastic, and autoimmune diseases.

Kidney ultrasound detected a loss of cortical-parenchymal differentiation with several isoechoic non-vascularized cysts, while a renal biopsy documented severe amyloidosis. On the basis of these findings and previous clinical presentation, a genetic test was performed to investigate autoinflammatory diseases: a T50M mutation was identified in the TNFRSF1A gene. Consequently, diagnosis of TRAPS with renal AA amyloidosis was made, and ANA therapy was started at the standard dose of 100 mg/day subcutaneously. After a short time, ANA dosage was increased to 200 mg/day because of the lack of a clear clinical and laboratory efficacy, bringing about the disappearance of all TRAPS-related clinical symptoms and a prompt decrease of ESR (33 mm/h), CRP (0.41 mg/dl), and SAA (14.34 mg/l). Furthermore, although GFR remained unchanged, proteinuria gradually decreased up to 7.13 g/24 h over a 6-month period. During the following year, ANA tapering was gradually started, firstly to 150 mg/day and then to the standard dosage of 100 mg/day without experiencing any TRAPS flare. To date, the patient is symptom-free and serologically stable after a 20-month period of ANA treatment.

Discussion

Over the past years, the inhibition of tumor necrosis factor-α has represented the first-line treatment option for TRAPS patients. Specifically, etanercept (ETN) has proven to be effective in two small prospective studies with a significant, although not complete, improvement of symptoms and inflammatory parameters. However, a loss of efficacy has also been identified over time, justifying the necessity of discontinuation in some cases [10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. In addition, the role of ETN in preventing or inducing a regression of reactive AA-amyloidosis remains controversial [17, 18]. More recently, laboratory and clinical evidences have disclosed the role of IL-1β in the pathogenesis of TRAPS, identifying IL-1 inhibition as a rational treatment choice for this disease. In particular, ANA revealed to be a valid and reliable weapon for both management of acute clinical manifestations and prevention of long-term TRAPS complications, including systemic AA-amyloidosis [9]. About this, according to a small retrospective study [10], ANA seemed to be superior to ETN, and good results were also obtained in patients with a previous loss of efficacy to ETN [13]. Notably, ANA has also revealed a good safety profile in relationship with the low frequency of adverse events and the relatively low risk of infections [19,20,21,22,23].

Always within IL-1 inhibition, according to small studies and case reports, good results have also been obtained with the fully human anti-IL-1β monoclonal antibody canakinumab (CAN), which was effective in controlling TRAPS symptoms, improving patients’ quality of life, and inducing the downregulation of IL-1-related pathways [24,25,26,27,28,29].

Although IL-1 inhibition has shown good maneuverability in terms of dose adjustments after a lack or inadequate efficacy [19], only few data are available on the safety of anti-IL-1 treatment in patients with severe kidney failure. In this regard, since renal excretion is the main route of elimination of ANA, a decrease in renal function entails a proportionate contraction of drug clearance with a higher tissue concentration and longer half-life [30,31,32,33]. For these reasons, the occurrence of side effects could be facilitated by the increased bioavailability of the drug, and ANA is indeed contraindicated in patients with severe impairment of renal function (GFR <30 ml/min). However, the few data currently available on ANA employment in cases of severe kidney impairment do not show increased occurrence of adverse events [34,35,36,37]. In particular, based on a retrospective analysis of 12 gout patients with severe kidney failure and other comorbidities, ANA showed to be well-tolerated in spite of one de novo leukopenia, developed within 24 h from the first ANA administration and one herpes zoster occurring 1 day after completing a 6-day course of ANA. Nevertheless, although the majority of patients presented an active infection prior to receiving ANA, this treatment did not appear to affect the response to antibiotic therapy, and one patient with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis received ANA prior to initiating antibiotic treatment without any worsening of tubercular disease [34]. Similarly, no adverse events were reported in small groups of patients treated with ANA and affected by renal amyloidosis related to familial Mediterranean fever [35, 36].

By presenting this case report, we remark the safety of IL-1 inhibition in one patient with end-stage kidney failure due to TRAPS-related amyloidosis, even when ANA was administered at double the standard dosage. However, in our patient, the clinical context required a specific treatment with IL-1 inhibition in order to solve systemic inflammation and contain amyloid deposition. Actually, clinical and serological remission was achieved in our patient without further compromising GFR and with no side effects. In addition, in line with our recent analysis on IL-1 inhibition in patients with different inflammatory disorders [19], increasing the dosage—after an initial lack of efficacy—proved to induce a complete clinical response. Moreover, the gradual tapering of ANA allowed a stable disease control despite the initial poor response. As a result, beyond the favorable impact of IL-1 blockade on proteinuria, confirmed also by other case reports [37,38,39,40,41], IL-1 inhibition might facilitate the access to kidney transplantation by stabilizing the inflammatory clinical framework in patients with autoinflammatory diseases complicated by severe renal amyloidosis [35].

In conclusion, we report about the safety of ANA administered up to 200 mg/day in one patient with TRAPS complicated by renal amyloidosis and severe kidney failure without recording any adverse event. Although wider clinical trials are required to take firm conclusions on this issue, the data available so far suggest that administration of ANA in patients with impaired renal function does not necessarily increase the risk of occurrence of adverse events.

References

Williamson LM, Hull D, Mehta R, Reeves WG, Robinson BH, Toghill PJ (1982) Familial Hibernian fever. Q J Med 51:469–480

Rigante D, Lopalco G, Vitale A, Lucherini OM, De Clemente C, Caso F et al (2014) Key facts and hot spots on tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome. Clin Rheumatol 33:1197–1207

Rigante D, Frediani B, Galeazzi M, Cantarini L (2013) From the Mediterranean to the sea of Japan: the transcontinental odyssey of autoinflammatory diseases. Biomed Res Int 2013:485103

Rigante D, Vitale A, Lucherini OM, Cantarini L (2014) The hereditary autoinflammatory disorders uncovered. Autoimmun Rev 13:892–900

Lachmann HJ, Papa R, Gerhold K, Obici L, Touitou I, Cantarini L, et al; Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organisation (PRINTO), the EUROTRAPS and the Eurofever Project (2014) The phenotype of TNF receptor-associated autoinflammatory syndrome (TRAPS) at presentation: a series of 158 cases from the Eurofever/EUROTRAPS international registry. Ann Rheum Dis 73:2160–2167

Rigante D (2017) A systematic approach to autoinflammatory syndromes: a spelling booklet for the beginner. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 9:1–27

Rigante D, Lopalco G, Vitale A, Lucherini OM, Caso F, De Clemente C et al (2014) Untangling the web of systemic autoinflammatory diseases. Mediat Inflamm 2014:948154

Cantarini L, Lucherini OM, Muscari I, Frediani B, Galeazzi M, Brizi MG et al (2012) Tumour necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS): state of the art and future perspectives. Autoimmun Rev 12:38–43

ter Haar NM, Oswald M, Jeyaratnam J, Anton J, Barron KS, Brogan PA et al (2015) Recommendations for the management of autoinflammatory diseases. Ann Rheum Dis 74:1636–1644

ter Haar N, Lachmann H, Özen S, Woo P, Uziel Y, Modesto C, et al; Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organisation (PRINTO) and the Eurofever/Eurotraps Projects (2013) Treatment of autoinflammatory diseases: results from the Eurofever Registry and a literature review. Ann Rheum Dis 72:678–685

Cantarini L, Lucherini OM, Galeazzi M, Fanti F, Simonini G, Baldari CT et al (2009) Tumour necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome caused by a rare mutation in the TNFRSF1A gene, and with excellent response to etanercept treatment. Clin Exp Rheumatol 27:890–891

Cantarini L, Rigante D, Lucherini OM, Cimaz R, Laghi Pasini F, Baldari CT et al (2010) Role of etanercept in the treatment of tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome: personal experience and review of the literature. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol 23:701–707

Bulua AC, Mogul DB, Aksentijevich I, Singh H, He DY, Muenz LR et al (2012) Efficacy of etanercept in the tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome: a prospective, open-label, dose-escalation study. Arthritis Rheum 64:908–913

Drewe E, McDermott EM, Powell PT, Isaacs JD, Powell RJ (2003) Prospective study of anti-tumour necrosis factor receptor superfamily 1B fusion protein, and case study of anti-tumour necrosis factor receptor superfamily 1A fusion protein, in tumour necrosis factor receptor associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS): clinical and laboratory findings in a series of seven patients. Rheumatology (Oxford) 42:235–239

Drewe E, Powell RJ, Mc Dermott EM (2007) Comment on: failure of anti-TNF therapy in TNF receptor 1-associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS). Rheumatology (Oxford) 46:1865–1866

Lane T, Loeffler JM, Rowczenio DM, Gilbertson JA, Bybee A, Russell TL et al (2013) AA amyloidosis complicating the hereditary periodic fever syndromes. Arthritis Rheum 65:1116–1121

Drewe E, Huggins ML, Morgan AG, Cassidy MJ, Powell RJ (2004) Treatment of renal amyloidosis with etanercept in tumour necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome. Rheumatology (Oxford) 43:1405–1408

Simsek I, Kaya A, Erdem H, Pay S, Yenicesu M, Dinc A (2010) No regression of renal amyloid mass despite remission of nephrotic syndrome in a patient with TRAPS following etanercept therapy. J Nephrol 23:119–123

Vitale A, Insalaco A, Sfriso P, Lopalco G, Emmi G, Cattalini M, et al (2016) A snapshot on the on-label and off-label use of the interleukin-1 inhibitors in Italy among rheumatologists and pediatric rheumatologists: a nationwide multi-center retrospective observational study. Front Pharmacol 24;7:380.

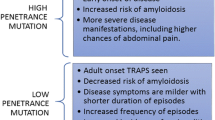

Ravet N, Rouaghe S, Dodé C, Bienvenu J, Stirnemann J, Lévy P et al (2006) Clinical significance of P46L and R92Q substitutions in the tumour necrosis factor superfamily 1A gene. Ann Rheum Dis 65:1158–1162

Rossi-Semerano L, Fautrel B, Wendling D, Hachulla E, Galeotti C, Semerano L, et al; MAIL1 (Maladies Auto-inflammatoires et Anti-IL-1) study Group on behalf of CRI (Club Rheumatisme et Inflammation) (2015) Tolerance and efficacy of off-label anti-interleukin-1 treatments in France: a nationwide survey. Orphanet J Rare Dis 15:10–19.

Cantarini L, Lopalco G, Caso F, Costa L, Iannone F, Lapadula G et al (2015) Effectiveness and tuberculosis-related safety profile of interleukin-1 blocking agents in the management of Behçet’s disease. Autoimmun Rev 14:1–9

Emmi G, Talarico R, Lopalco G, Cimaz R, Cantini F, Viapiana O et al (2016) Efficacy and safety profile of anti-interleukin-1 treatment in Behçet’s disease: a multicenter retrospective study. Clin Rheumatol 35:1281–1286

Brizi MG, Galeazzi M, Lucherini OM, Cantarini L, Cimaz R (2012) Successful treatment of tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome with canakinumab. Ann Intern Med 156:907–908

Arad U, Niv E, Caspi D, Elkayam O (2012) “TRAP” the diagnosis: a man with recurrent episodes of febrile peritonitis, not just familial Mediterranean fever. Isr Med Assoc J 14:229–231

Gattorno M, Obici L, Meini A, Tormey V, Abrams K, Davis N et al (2012) Efficacy and safety of canakinumab in patients with TNF receptor associated periodic syndrome [abstract]. Arthritis Rheum 64:749

La Torre F, Muratore M, Vitale A, Moramarco F, Quarta L, Cantarini L (2015) Canakinumab efficacy and long-term tocilizumab administration in tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS). Rheumatol Int 35:1943–1947

Torene R, Nirmala N, Obici L, Cattalini M, Tormey V, Caorsi R et al (2017) Canakinumab reverses overexpression of inflammatory response genes in tumour necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis 76:303–309

Gattorno M, Obici L, Cattalini M, Tormey V, Abrams K, Davis N et al (2017) Canakinumab treatment for patients with active recurrent or chronic TNF receptor-associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS): an open-label, phase II study. Ann Rheum Dis 76:173–178

Meibohm B, Zhou H (2012) Characterizing the impact of renal impairment on the clinical pharmacology of biologics. J Clin Pharmacol 52(1 Suppl):54S–62S

Kim DC, Reitz B, Carmichael DF, Bloedow DC (1995) Kidney as a major clearance organ for recombinant human interleukin-1 receptor antagonist. J Pharm Sci 84:575–580

Yang B, Frazier J, McCabe D, Young J (2000) Population pharmacokinetics of recombinant interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (anakinra) in subjects with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Arthritis Rheum 43(Suppl):S153

Yang BB, Baughman S, Sullivan JT (2003) Pharmacokinetics of anakinra in subjects with different levels of renal function. Clin Pharmacol Ther 74:85–94

Thueringer JT, Doll NK, Gertner E (2015) Anakinra for the treatment of acute severe gout in critically ill patients. Semin Arthritis Rheum 45:81–85

Stankovic Stojanovic K, Delmas Y, Torres PU, Peltier J, Pelle G, Jéru I et al (2012) Dramatic beneficial effect of interleukin-1 inhibitor treatment in patients with familial Mediterranean fever complicated with amyloidosis and renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant 27:1898–1901

Özçakar ZB, Özdel S, Yılmaz S, Kurt-Şükür ED, Ekim M, Yalçınkaya F (2016) Anti-IL-1 treatment in familial Mediterranean fever and related amyloidosis. Clin Rheumatol 35:441–446

Obici L, Meini A, Cattalini M, Chicca S, Galliani M, Donadei S et al (2011) Favourable and sustained response to anakinra in tumour necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS) with or without AA amyloidosis. Ann Rheum Dis 70:1511–1512

Sevillano ÁM, Hernandez E, Gonzalez E, Mateo I, Gutierrez E, Morales E et al (2016) Anakinra induces complete remission of nephrotic syndrome in a patient with familial Mediterranean fever and amyloidosis. Nefrologia 36:636

Aït-Abdesselam T, Lequerré T, Legallicier B, François A, Le Loët X, Vittecoq O (2010) Anakinra efficacy in a Caucasian patient with renal AA amyloidosis secondary to cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome. Joint Bone Spine 77:616–617

Sozeri B, Gulez N, Ergin M, Serdaroglu E (2016) The experience of canakinumab in renal amyloidosis secondary to familial Mediterranean fever. Mol Cell Pediatr 3:33

Scarpioni R, Rigante D, Cantarini L, Ricardi M, Albertazzi V, Melfa L et al (2015) Renal involvement in secondary amyloidosis of Muckle-Wells syndrome: marked improvement of renal function and reduction of proteinuria after therapy with human anti-interleukin-1β monoclonal antibody canakinumab. Clin Rheumatol 34:1311–1316

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

None.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gentileschi, S., Rigante, D., Vitale, A. et al. Efficacy and safety of anakinra in tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS) complicated by severe renal failure: a report after long-term follow-up and review of the literature. Clin Rheumatol 36, 1687–1690 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-017-3688-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-017-3688-4