Abstract

Lupus nephritis is a life-threatening complication of systemic lupus erythematosus. The standard treatment for this condition, including corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide, results in a 70 % remission rate at 12 months, but it is also associated with significant morbidity. Rituximab, a chimeric anti-CD20 antibody, could be useful, given the central role of B cells in the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Case reports and retrospective series have reported that rituximab is effective for refractory lupus nephritis. However, the double-blind, placebo-controlled LUNAR trial failed to meet its end point. We studied clinical, biological, and immunological data on 17 patients who received rituximab as an induction treatment for refractory lupus nephritis at the University Hospital Center of Bordeaux. A complete treatment response was defined as a normal serum creatinine with inactive urinary sediment and 24-h urinary albumin <0.5 g and a partial response (PR) as a >50 % improvement in all of the renal parameters that were abnormal at baseline, with no deterioration in any parameter. Seventeen patients received rituximab as induction treatment for lupus nephritis refractory to standard treatment by cyclophosphamide. After a follow-up of 12 months, complete or partial renal remission was achieved in 53 % patients. Rituximab therapy resulted in a significant improvement in proteinuria and steroid dose tapering in all patients. Rituximab should be considered as a treatment option for refractory lupus glomerulonephritis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Lupus nephritis (LN) is one of the most severe manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and may affect more than 50 % of patients [1]. Kidney-specific lesions and treatment-linked toxicities contribute to the high morbidity and mortality of LN. Approximately 10 % of all patients who are affected by LN will develop end-stage renal failure. The standard treatment for active proliferative LN includes corticosteroids (CS) in conjunction with cyclophosphamide (CYC) or mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) [2, 3]. Although the renal response rates among patients receiving this treatment reach 50–80 % at 1 year, many of these responses are partial. Therefore, treatments that are more effective, less toxic, and fertility-sparing are needed especially in the management of refractory LN (defined as LN resistant to standard treatment). B cells play a central role in the pathogenesis of SLE; B cell overactivity participates in the activation of the autoimmune processes associated with SLE, such as the production of autoantibodies and various cytokines, and the activation of potent antigen-presenting cells [4]. B cell-targeted therapy has been introduced for SLE therapy [5]. However, in two recent randomized placebo-controlled trials with SLE patients, the chimeric anti-CD20 antibody, rituximab (RTX), failed to achieve the primary end points [6, 7]. In contrast, RTX has been reported to be a promising treatment option in several case series and off-label studies in patients with refractory SLE [8–14]. Here, we report on a chart review investigating the effectiveness and safety of RTX in patients with refractory LN.

Methods

Patients

We analyzed data on patients followed for refractory LN (i.e., resistant to standard treatment with CYC) who were treated with RTX at the University Hospital Center of Bordeaux. All patients had previously been treated with CYC and then gave informed consent for receiving RTX for LN. Eligible patients were adults and had a diagnosis of SLE according to the revised American College of Rheumatology criteria [15].

Lupus nephritis definition and response criteria

LN was defined according to the 2003 International Society of Nephrology/Renal Pathology Society (ISN/RPS) [16] and confirmed on a renal biopsy within 6 months prior to inclusion. The primary efficacy end point was renal response at week 52 after the first infusion of rituximab based on the European consensus statement on the terminology used in the management of lupus glomerulonephritis [17]. A complete renal response (CRR) was defined as proteinuria under 0.2 g/24 h, a glomerular filtration rate stable or up to 90 ml/min, and inactive urinary sediment. A partial renal response (PRR) was defined as proteinuria between 0.2 g/24 h and 0.5 g/24 h, a glomerular filtration rate stable or up to 90 ml/min, and inactive urinary sediment, and the absence of response (NRR) was defined as proteinuria over 0.5 g/24 h, a deterioration in the glomerular filtration rate, and active urinary sediment. We also recorded the SLEDAI score, adverse effects, autoantibody titers (anti-nuclear and anti-double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) antibodies), and steroid doses.

Statistical analyses

Quantitative variables are expressed as the median and interquartile range. Differences in continuous variables were analyzed using non-parametric tests, and differences between paired data were determined using a paired t test. All statistical analyses were performed with PASW Statistics 18 for Windows (IBM SPSS, Chicago, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics at inclusion are described in Table 1. Seventeen patients were included; the median age at inclusion was 36 years (30–44), and the median SLE duration was 12 years (8–19). The median number of LN flares before RTX treatment was 3. All patients had previously been treated with CYC for LN flares, with a median rate of 2 CYC lines (i.e., six pulses of 500 mg of CYC for 15 days); other LN flares were managed with MMF, mycophenolic acid (MPA), or azathioprine (AZT). Renal biopsy showed class IV nephritis in 10 patients, class III nephritis in six patients, and class II nephritis resistant to CS in one patient. Three patients presented with simultaneous SLE extra-renal manifestations, two with articular involvement, and one with cutaneous vasculitis. The RTX doses were either 375 mg/m2 a week for 4 weeks (10 patients) or two infusions of 1 g at day 0 and day 15 (seven patients). In all cases, RTX was given in conjunction with prednisone pulses, with doses ranging from 100 to 750 mg. The epidemiologic and clinical features according to the renal responses are shown in Table 2. Nine of the 17 patients (53 %) reached a global renal response; CRR was achieved in four patients, and PRR was achieved in five patients. Eight patients had no response (NRR). The highest rate of response was achieved in patients with class III nephritis (four of the six): two CRR and two PRR. The rate of response was 50 % in class IV nephritis. The patient with class II nephritis did not achieve a response.

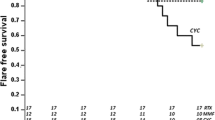

One year after RTX treatment, the median SLEDAI score was significantly decreased for all patients and for responder patients progressing from 10 (6–26) to 5 (0–13) (p < 0.0002) and from 8 (6–26) to 2 (0–12), respectively (p < 0.0039). Responder patients had a lower median baseline proteinuria compared to NRR patients, 2.35 g/24 h (0.68–6) and 4 g/24 h (2.7–26), respectively (p < 0.012). An improvement in proteinuria was observed in all groups of responders, from 3 g/24 h (0.65–3.8) at inclusion to 0.5 g/24 h (0–5) at 1 year (p < 0.0001). For patients with CRR and PRR, proteinuria tapered from 2.35 g/24 h at baseline to 0.28 g/24 h [0–0.5] at 1 year after rituximab treatment (p < 0.0039) and from 4 g/24 h to 1.32 g/24 h (0.76–5) (p < 0.0067) in NRR patients (Fig. 1a).

Evolution of proteinuria (a), prednisone dose (b), and anti-dsDNA rate (c) at inclusion (M0) and 1 year after the first rituximab infusion (M12) according to renal response. RR global renal response including CRR and PRR, CRR complete renal response, PRR partial renal response, NRR non-renal response

The median dose of prednisone 1 year after RTX was significantly decreased compared with the median dose of prednisone at inclusion in all patients; it dropped from 20 mg a day (0–40) to 5 mg a day (0–20), respectively (p < 0.002). Even NRR patients had their prednisone dose lowered from 9 mg (0–40) to 5 mg a day (0–20) (NS) (Fig. 1b). The median anti-dsDNA rate in responder patients was 153 UI/ml (20–1745) at inclusion and 36 UI /ml (5–860) 1 year after RTX therapy (p < 0.0039). For NRR patients, the rate was 186.5 UI/ml (31–1082) at inclusion and significantly decreased to 136.5 UI /ml 1 year after RTX therapy (16–713) (p < 0.039) (Fig. 1c). Only one notable adverse effect was reported; one patient presented with pyelonephritis due to Escherichia coli 2 years after the first rituximab infusion in the context of hypogammaglobulinemia.

Discussion

In the present study, RTX was effective in 53 % of patients with a history of LN refractory to CYC. One year after RTX treatment, we noted a drastic decrease in both proteinuria and the anti-dsDNA antibodies rate even in NRR-defined patients. Moreover, RTX treatment resulted in a significant decrease in the prednisone dose. RTX infusion was well tolerated in this study, with only one patient experiencing an adverse event. Our findings are in line with those of previous open-label studies of RTX in SLE [9, 11]. Prospective data from the French Autoimmunity and Rituximab (AIR) registry showed the safety and clinical efficacy of RTX and reported articular, renal, and hematologic improvements (72, 74, and 88 %, respectively) even among patients with refractory SLE [10]. In addition, patients with lupus nephritis in the European cohorts demonstrated a 67 % improvement at 1 year after RTX therapy [14]. In the Lupus Nephritis Assessment with Rituximab (LUNAR) trial, patients with proliferative (class III or IV) LN were randomized to RTX versus placebo and all patients were treated with high-dose glucocorticoids and MMF [7]. However, the primary end point for RTX was not met, although RTX treatment did improve serologic markers. It is important to note that our inclusion criteria differ from the LUNAR trial; all of the patients included in our study were refractory to CYC, whereas the LUNAR trial excluded patients who had previously been treated with CYC. The highest rates of response in our study were obtained with type III LN. These findings are in keeping with those of open series that found different rates of response according to the 2003 International Society of Nephrology/Renal Pathology Society (ISN/RPS) histopathological classification, with a threefold higher rate of CRR in patients with type III LN than in type IV [14]. This low rate of CRR in type IV LN could have contributed to the non-significant results of the LUNAR trial, in which two thirds of the patients had type IV LN [7].

The optimal dosing regimen for RTX in SLE remains unclear; in the randomized placebo-controlled trials, 1000 mg × 2 infusions were used [6, 7], whereas two different RTX schedules were used in the present study (1000 mg × 2 infusions and 375 mg/m2 × 4 infusions) but did not influence the response (data not shown). The immunosuppressant agents used in conjunction with RTX did not seem to influence the renal response because MMF, MPA, and HCQ were used equally in responders and NRR patients, but it is noteworthy that the prednisone doses at inclusion were higher in the responder patients. Other factors such as age and the clinical manifestations of SLE were similar between each group of responders. Nevertheless, the baseline SLEDAI was higher in the NRR patients than in CRR and PRR patients because of active urinary sediment with hematuria, which occurred in two thirds of patients with hematuria.

The limitations of our study include its relatively small sample size, its observational design, and the missing data including the measurement of the B cell counts and RTX human antichimeric antibody. In summary, RTX might not be recommended as a first-line treatment for patients with SLE who have the potential to respond well to conventional treatment. However, many studies including the present one have demonstrated that RTX is effective and relatively safe therapeutic option in patients with severe refractory LN. Future randomized controlled trials in patients with refractory SLE are required.

References

Feldman CH, Hiraki LT, Liu J et al (2013) Epidemiology and sociodemographics of systemic lupus erythematosus and lupus nephritis among US adults with Medicaid coverage, 2000–2004. Arthritis Rheum 65:753–63

Houssiau FA, Vasconcelos C, D’Cruz D et al (2002) Immunosuppressive therapy in lupus nephritis: the Euro-Lupus Nephritis Trial, a randomized trial of low-dose versus high-dose intravenous cyclophosphamide. Arthritis Rheum 46:2121–31

Appel GB, Contreras G, Dooley MA et al (2009) Mycophenolate mofetil versus cyclophosphamide for induction treatment of lupus nephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol JASN 20:1103–12

Tsokos GC (2011) Systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med 365:2110–21

Perosa F, Favoino E, Caragnano MA, Prete M, Dammacco F (2005) CD20: a target antigen for immunotherapy of autoimmune diseases. Autoimmun Rev 4:526–31

Merrill JT, Neuwelt CM, Wallace DJ et al (2010) Efficacy and safety of rituximab in moderately-to-severely active systemic lupus erythematosus: the randomized, double-blind, phase II/III systemic lupus erythematosus evaluation of rituximab trial. Arthritis Rheum 62:222–33

Rovin BH, Furie R, Latinis K et al (2012) Efficacy and safety of rituximab in patients with active proliferative lupus nephritis: the Lupus Nephritis Assessment with Rituximab study. Arthritis Rheum 64:1215–26

Pinto LF, Velásquez CJ, Prieto C, Mestra L, Forero E, Márquez JD (2011) Rituximab induces a rapid and sustained remission in Colombian patients with severe and refractory systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 20:1219–26

Gunnarsson I, Sundelin B, Jónsdóttir T, Jacobson SH, Henriksson EW, van Vollenhoven RF (2007) Histopathologic and clinical outcome of rituximab treatment in patients with cyclophosphamide-resistant proliferative lupus nephritis. Arthritis Rheum 56:1263–72

Terrier B, Amoura Z, Ravaud P et al (2010) Safety and efficacy of rituximab in systemic lupus erythematosus: results from 136 patients from the French AutoImmunity and Rituximab registry. Arthritis Rheum 62:2458–66

Bang S-Y, Lee CK, Kang YM et al (2012) Multicenter retrospective analysis of the effectiveness and safety of rituximab in Korean patients with refractory systemic lupus erythematosus. Autoimmune Dis 2012:565039

Lateef A, Lahiri M, Teng GG, Vasoo S (2010) Use of rituximab in the treatment of refractory systemic lupus erythematosus: Singapore experience. Lupus 19:765–70

Ramos-Casals M, Soto MJ, Cuadrado MJ, Khamashta MA (2009) Rituximab in systemic lupus erythematosus: a systematic review of off-label use in 188 cases. Lupus 18:767–76

Díaz-Lagares C, Croca S, Sangle S et al (2012) Efficacy of rituximab in 164 patients with biopsy-proven lupus nephritis: pooled data from European cohorts. Autoimmun Rev 11:357–64

Hochberg MC (1997) Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 40:1725

Weening JJ, D’Agati VD, Schwartz MM et al (2004) The classification of glomerulonephritis in systemic lupus erythematosus revisited. J Am Soc Nephrol JASN 15:241–50

Gordon C, Jayne D, Pusey C et al (2009) European consensus statement on the terminology used in the management of lupus glomerulonephritis. Lupus 18:257–63

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

None.

Additional information

Anne Contis and Helene Vanquaethem contributed equally to this work.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Contis, A., Vanquaethem, H., Truchetet, ME. et al. Analysis of the effectiveness and safety of rituximab in patients with refractory lupus nephritis: a chart review. Clin Rheumatol 35, 517–522 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-015-3166-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-015-3166-9