Abstract

The aim is to study the efficacy and safety of etoricoxib in the treatment of acute gout, as compared with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). We conducted a computerized search of electronic databases: PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, China Biology Medicine disc, and Cochrane Library. The search terms were as follows: gout arthritis, tophus, etoricoxib, indometacin naproxen, diclofenac, and NSAIDs. Articles were searched from 1983 until August 2014. A manual search of peer-reviewed English documents was performed by cross-checking the bibliographies of selected studies. These trials reported pain relief as the primary outcome. Tenderness, swelling, patients’ global assessments of response to treatment, and investigators’ global assessments of response to treatment were reported as the secondary outcomes. All adverse events were recorded for safety assessment. Six trials including 851 patients were identified. Both etoricoxib and NSAIDs had an effect on inflammation and analgesia. Compared with indometacin and diclofenac, etoricoxib had a lower incidence of adverse events. Etoricoxib 120 mg administered orally once daily has the same efficacy on acute gout as indometacin and diclofenac. Etoricoxib is tolerated better by patients than NSAIDs such as indometacin and diclofenac.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Acute gouty arthritis is the most common form of inflammatory joint disease in males over 40 years [1]. It is estimated that 0.5–2.8 % of males have suffered from this disease, while there is a lower incidence among females [2]. One third of female patients suffering from gout are premenopausal and have an unexpectedly high prevalence of lithiasis [3]. Epidemiologic evidence suggests that the incidence of gout is steadily increasing and is connected with longevity, obesity, coexisting comorbidities, and iatrogenic causes that contribute to hyperuricemia such as diuretic use [4]. The prevalence is much higher among individuals with a positive family history [2], but the precise mechanism is unclear. The primary symptom of acute gouty arthritis is pain and typically involves smaller appendicular joints like the metatarsophalangeal joints [5]. Therapy is directed at controlling inflammation and relieving joint pain [6]. Treatments aimed at modulating the inflammatory process have changed little over the last 40 years [7], and there are still limitations in controlling inflammation and relieving pain. In 2012, the American College of Rheumatology Guidelines for Management of Gout [8] recommended multiple modalities (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), corticosteroids by different routes, and oral colchicines) as appropriate initial therapeutic options for acute gout attacks. For NSAIDs, they recommended naproxen, indometacin, and sulindac. However, the guidelines do not recommend a specific NSAID for first-line treatment. Cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) inhibitors are an option for patients with gastrointestinal contraindications or intolerance to NSAIDs. Several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have been published that support the efficacy of COX-2 inhibitors like etoricoxib, lumiracoxib, and celecoxib [9–11]. However, there is still not much evidence to indicate efficacy of these treatments. Etoricoxib is a new highly selective COX-2 inhibitor [12, 13] that has shown anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and antipyretic activities in models of acute and chronic pain and inflammation, and it has better GI tolerability compared with NSAIDs [14–16]. We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to study the efficacy and safety of etoricoxib in the treatment of acute gout, as compared with NSAIDs.

Materials and methods

Literature search

We conducted a computerized search of electronic databases: PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, China Biology Medicine disc, and Cochrane Library. The search terms were as follows: gout, etoricoxib, indometacin diclofenac, and NSAIDs. Articles were searched from 1983 until August 2014. A manual search of peer-reviewed English documents was performed by cross-checking the bibliographies of selected studies. If multiple articles of the same patient population were identified, we only included the published report with the largest sample size. We did not search for unpublished investigations.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included articles with patients diagnosed according to the American Rheumatology Association diagnostic criteria for acute gout [17]. Articles were excluded if they were editorials, observational studies, case reports, author replies, review articles, opinions, comments, or any other non-RCTs. Studies not pertinent to gout, hyperuricemia, or tophus were excluded. Studies that included other arthritic diseases that could confound or interfere with efficacy evaluations or those that did not report clinical outcomes were also excluded.

Data analysis

Data extraction was performed by SZ and checked by JW using a predefined data extraction form. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion between reviewers. For each study, reviewers extracted data that were deemed to potentially impact efficacy outcomes, such as study population (percent women, mean age, and severity of gout arthritis), study design (duration, concomitant analgesic use, and intervention method), and outcomes (patient’s assessment of pain, tenderness and swelling score at endpoint, and change from baseline with measures of variance; adverse events). Two authors (SZ and YZ) assessed included articles independently and used the “assessing risk of bias” tool recommended in the Cochrane Handbook 5.0.2 to evaluate the risk of bias of included trials. The tool assesses factors including random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other biases. Another two authors (ZW and LP) settled disputes when there was no consensus.

For continuous outcomes, we pooled data with the weighted mean difference (WMD) of the final value across groups. For dichotomous data, we calculated the relative risks (RRs) and 95 % confidence interval (CI) for each study. The meta-analysis was performed on data extracted from the studies. If the standard deviations (SDs) were not reported, we calculated the SD with the 95 % CI. Before data analysis, the Q statistic was calculated to assess heterogeneity. We used the fixed effect model when the effects were assumed to be homogenous (p > 0.05) and the random effect model when they were heterogeneous (p < 0.05). All statistical tests and risk of bias were calculated with RevMan 5.2 (Cochrane Collaboration, London, UK).

Results

Identification and selection of studies

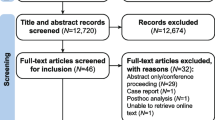

A total of 165 records (86 from EMBASE, 5 from Cochrane Library, 13 from PubMed MEDLINE, 44 from Web of Science, 16 from China Biology Medicine disc, and 1 identified from other sources) were obtained from the initial search. All studies were selected strictly according to the criteria described. After 41 duplicates, 73 reviews, 11 conference papers, 4 case reports, 4 short surveys, 4 notes, and 3 editorials were removed. Twenty-five studies remained for the full-text review. Nineteen studies were ultimately excluded because they are not related to acute gout or the control group did not take NSAIDs. Finally, six trials were included [9, 18–22]. The selection process and reasons for exclusion are summarized in Fig. 1.

Description and quality of studies

In three articles [9, 18, 19] directly comparing etoricoxib and indometacin for the treatment of acute gout, all trials reported pain relief (patients’ personal assessments of pain in the study joint on a 0–4-point scale) as the primary outcome. Tenderness, swelling, patients’ global assessments of response to treatment, and investigators’ global assessments of response to treatment were reported as the secondary outcomes. Another three [20–22] were comparing etoricoxib and diclofenac for the treatment of acute gout, two trials [20, 21] assessed pain relief by a visual analogue scale, and another one was [22] assessed by the criteria of Mazur (1979). Both six articles reported adverse events for safety assessment. Six articles were included in this meta-analysis. Studies were evaluated with the “assessing risk of bias” tool, and results are summarized in Fig. 2.

All studies aimed to assess the efficacy and safety of etoricoxib for the treatment of acute gout. The control group in each study was indometacin and diclofenac. All eligible patients were 18 years or older with acute gout associated with moderate, severe, or extreme pain and meeting the American Rheumatology Association diagnostic criteria for acute gout [17]. The three studies included 851 patients. Etoricoxib, indometacin, and diclofenac were not the only drugs given to patients. Patients could take low-dose aspirin (<325 mg daily), allopurinol if taken for at least two weeks before the trials, and colchicines (<1.2 mg daily) if taken at a stable dose for more than 30 days before the trials. Studies were not included if patients were allowed any other NSAIDs or analgesics within 48 h before baseline assessments, within six hours of baseline assessments, or for the duration of the study. The demographic characteristics of patients are summarized in Table 1.

Efficacy of the etoricoxib

We assessed the efficacy of etoricoxib in the treatment of acute gout by the patient’s assessment of pain, investigator’s assessed tenderness of study joints and swelling, patient’s global assessments of response to treatment, and investigators global assessments of response to treatment. Because of high heterogeneity, for assessment of pain, the data cannot be analyzed together. Three studies [9, 18, 19] measured the pain intensity with a 0–4-point scale for 5 days, and two studies [20, 21] measured the pain relief by a visual analogue scale for 7 days, with the overall pooled WMD of −0.10 (95% CI: −0.25 to 0.06, p = 0.22) and −0.46 (95% CI: −0.51 to −0.41, p < 0.00001) as summarized in Fig. 3. It has revealed a different outcome.

For the remaining four outcomes, only three articles [9, 18, 19] have available data; we made a meta-analysis, and there were overall pooled WMDs of −0.14 (95% CI: −0.31 to 0.03, p = 0.11), −0.16 (95% CI: −0.33 to 0.02, p = 0.08), −0.10 (95% CI: −0.28 to 0.07, p = 0.26), and −0.29 (95% CI: −0.46 to −0.11, p = 0.26), respectively. There was no significant difference between the two interventions, as shown in Fig. 4.

Safety of etoricoxib

Safety assessment for the interventions was calculated by pooling relative data. Adverse events (AEs) were reported in each trial, including any AE, drug-related AEs, and serious AEs. For any AE, the pooled RR value was 0.77 (95% CI: 0.64 to 0.93, p = 0.006). For drug-related AEs, the pooled RR was 0.64 (95% CI: 0.50 to 0.81, p = 0.0003). There was a significant difference between the two interventions for drug-related AEs. The etoricoxib group had fewer AEs than the NSAID group. For serious AEs, the pooled RR was 0.42 (95% CI: 0.09 to 1.93, p = 0.27) (Fig. 5).

Drug-related AEs included abdominal distention, diarrhea, stomachache, dizziness, chills, fever, edema of the legs or feet, erythema, or cardiovascular symptoms. The most disparate among the groups were dizziness and gastrointestinal side effects. The pooled RR for the gastrointestinal AE was 0.42 (95% CI: 0.27 to 0.66, p = 0.0002), which was significantly different between the two interventions. Patients tolerated the etoricoxib better than those in the NSAID group as shown in Fig. 6. For dizziness, because of the deficient data, we only pooled two trials [19, 9] and found a pooled RR value of 0.37 (95% CI: 0.16 to 0.85, p = 0.02). Dizziness was significantly more common in the indometacin group than in the etoricoxib group as shown in Fig. 6.

Discussion

Acute gouty arthritis is the most common form of inflammatory joint disease. The primary symptom of acute gout is pain. Optimal therapy is directed at controlling inflammation and analgesia [23]. NSAIDs are considered to be the most potent NSAID for the treatment of gout [1]. Etoricoxib, a novel cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) inhibitor, has anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and antipyretic activities in models of acute or chronic pain and inflammation in osteoarthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and rheumatoid arthritis [24–27]. To our knowledge, this is the first quantitative comparative meta-analysis of studies directly comparing etoricoxib and NSAIDs for the treatment of acute gout. Ultimately, six RCTs were included, and a systematic review and meta-analysis were performed to replicate and confirm the results of the studies. In order to assess the efficacy and safety of etoricoxib, we extracted relative data as much as possible, and we pooled the outcome whenever possible.

For the efficacy assessment, the overall pooled WMD of −0.10 (95% CI: −0.25 to 0.06, p = 0.22) and −0.46 (95% CI: −0.51 to −0.41, p < 0.00001) is for pain relief. It has revealed a different outcome mainly because one article’s [20] mean difference and 95 % CI was −0.64 [−0.51 to −0.41]. In summary, we believe there was no significant difference between etoricoxib and NSAIDs such as indometacin and diclofenac. For the remaining four outcomes, only three articles [9, 18, 19] have available data; we made a meta-analysis, and there were overall pooled WMDs of −0.14 (95% CI: −0.31 to 0.03, p = 0.11), −0.16 (95% CI: −0.33 to 0.02, p = 0.08), −0.10 (95% CI: −0.28 to 0.07, p = 0.26), and −0.29 (95% CI: −0.46 to −0.11, p = 0.26), respectively. There was no significant difference between the two interventions, as shown in Fig. 4. The overall outcome showed there was no significant difference among the two interventions after 5 or 7 days of treatment. Therefore, etoricoxib 120 mg administered orally once daily has the same anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects as NSAIDs.

For the safety assessment, any AE, drug-related AEs, and serious AEs, had pooled RR values of 0.77 (95% CI: 0.64 to 0.93, p = 0.006), 0.64 (95% CI: 0.50 to 0.81, p = 0.0003), and 0.42 (95% CI: 0.09 to 1.93, p = 0.27). These results indicate that etoricoxib has fewer complications than NSAIDs. For drug-related AEs, there was a significant difference between the two interventions, with etoricoxib having fewer complications than NSAIDs. For gastrointestinal tract side effects, the pooled RR was 0.42 (95% CI: 0.27 to 0.66, p = 0.0002). For dizziness, the pooled RR value was 0.37 (95% CI: 0.16 to 0.85, p = 0.02). Both of these AEs were significantly more common in the NSAID group than in the etoricoxib group. All trials apply the intervention methods of etoricoxib 120 mg administered orally once daily, and Leclercq [28] recommended etoricoxib at a dosage of 60 mg/day for osteoarthritis, 90 mg/day for rheumatoid arthritis, and 120 mg/day for acute gout. So we believe that etoricoxib 120 mg administered orally once daily is effective for treatment of acute gout.

As a meta-analysis for randomized studies, there are several limitations to our studies. First, this meta-analysis is limited primarily because of the small quantity of original studies, and the included studies have small sample sizes. To confirm this assessment, high-quality and more RCTs must be conducted. Furthermore, because of small sample size, subgroup analysis was not performed on polyarticular and monoarticular gouts. Second, all of the studies included in this meta-analysis are RCTs, but in some articles, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, and other biases were unclear; these studies were more likely to suffer from various kinds of bias. Furthermore, confounding factors such as underlying disease and the use of other drugs can confuse the outcome. However, there is still no way for controlling these confounding factors and bias and no established method for assessing how these confounding factors and bias affect the overall outcome. Third, no authors were contacted for further information. We extracted the data either directly from the article or through extrapolation by us.

Conclusion

We believe, from this meta-analysis, we found that etoricoxib has similar anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects as indometacin in the treatment of acute gout. Furthermore, etoricoxib has a significantly lower risk of AEs than indometacin. Etoricoxib 120 mg administered orally once daily may be effective for the treatment of acute gouty arthritis.

Abbreviations

- NSAIDS:

-

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- RCTs:

-

Randomized controlled trials

- AEs:

-

Adverse events

- EG:

-

Experimental group

- CG:

-

Control group

- SS:

-

Sample size

- RR:

-

Relative risk

- WMD:

-

Weighted mean difference

References

Harris MD, Siegel LB, Alloway JA (1999) Gout and hyperuricemia. Am Fam Physician 59(4):925–934

Fam AG (1998) Gout in the elderly. Clinical presentation and treatment. Drugs Aging 13(3):229–243

Garcia-Mendez S, Beas-Ixtlahuac E, Hernandez-Cuevas C et al (2012) Female gout: age and duration of the disease determine clinical presentation. J Clin Rheumatol Pract Rep Rheum Musculoskelet Dis 18(5):242–245

So A, De Smedt T, Revaz S, Tschopp J (2007) A pilot study of IL-1 inhibition by anakinra in acute gout. Arthritis Res Ther 9(2):R28. doi:10.1186/ar2143

Buckley TJ (1996) Radiologic features of gout. Am Fam Physician 54(4):1232–1238

Terkeltaub RA, Ginsberg MH (1988) The inflammatory reaction to crystals. Rheum Dis Clin N Am 14(2):353–364

Wortmann RL (1998) Effective management of gout: an analogy. Am J Med 105(6):513–514

Khanna D, Khanna PP, Fitzgerald JD, Singh MK, Bae S, Neogi T et al (2012) 2012 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. Part 2: therapy and antiinflammatory prophylaxis of acute gouty arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 64(10):1447–1461

Schumacher HR Jr, Boice JA, Daikh DI et al (2002) Randomised double blind trial of etoricoxib and indometacin in treatment of acute gouty arthritis. BMJ (Clin Res ed) 324(7352):1488–1492

Willburger RE, Mysler E, Derbot J, Jung T et al (2007) Lumiracoxib 400 mg once daily is comparable to indomethacin 50 mg three times daily for the treatment of acute flares of gout. Rheumatology (Oxford, England) 46(7):1126–1132

Schumacher HR, Berger MF, Li-Yu J, Perez-Ruiz F et al (2012) Efficacy and tolerability of celecoxib in the treatment of acute gouty arthritis: a randomized controlled trial. J Rheumatol 39(9):1859–1866

Riendeau D, Percival MD, Brideau C, Charleson S et al (2001) Etoricoxib (MK-0663): preclinical profile and comparison with other agents that selectively inhibit cyclooxygenase-2. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 296(2):558–566

Leung AT, Malmstrom K, Gallacher AE, Sarembock B et al (2002) Efficacy and tolerability profile of etoricoxib in patients with osteoarthritis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo and active-comparator controlled 12-week efficacy trial. Curr Med Res Opin 18(2):49–58

Donnelly MT, Hawkey CJ (1997) Review article: COX-II inhibitors—a new generation of safer NSAIDs? Aliment Pharmacol Ther 11(2):227–236

Peura DA (2002) Gastrointestinal safety and tolerability of nonselective nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents and cyclooxygenase-2-selective inhibitors. Cleve Clin J Med 69(Suppl 1):Si31–Si39

Scheiman JM (2002) Outcomes studies of the gastrointestinal safety of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors. Cleve Clin J Med 69(Suppl 1):Si40–Si46

Wallace SL, Robinson H, Masi AT, Decker JL, McCarty DJ, Yu TF (1977) Preliminary criteria for the classification of the acute arthritis of primary gout. Arthritis Rheum 20(3):895–900

Rubin BR, Burton R, Navarra S, Antigua J et al (2004) Efficacy and safety profile of treatment with etoricoxib 120 mg once daily compared with indomethacin 50 mg three times daily in acute gout: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 50(2):598–606

Li T, Chen SL, Dai Q, Han XH et al (2013) Etoricoxib versus indometacin in the treatment of Chinese patients with acute gouty arthritis: a randomized double-blind trial. Chin Med J 126(10):1867–1871

Lu JL (2014) Clinical efficacy of etoricoxib in the treatment of acute gouty arthritis. Pract Pharm Clin Remedies 17(4):451–453

Ye Q, Du PF, Wang ZZ et al (2010) Effect of etoricoxib on acute gout. Clin Educ Gen Pract 8(4):391–393

Guo M, Cheng ZF, Hu YH et al (2014) Evaluation of efficacy of COX-2 inhibitors in the treatment of patients with acute gouty arthritis. Prog Mod Biomed 14(29):5747–5750

Pouliot M, James MJ, McColl SR, Naccache PH, Cleland LG (1998) Monosodium urate microcrystals induce cyclooxygenase-2 in human monocytes. Blood 91(5):1769–1776

Cochrane DJ, Jarvis B, Keating GM (2002) Etoricoxib. Drugs 62(18):2637–2651, discussion 2652–2633

Schumacher HR Jr (2004) Management strategies for osteoarthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and gouty arthritis. J Clin Rheumatol Pract Rep Rheum Musculoskelet Dis 10(3 Suppl):S18–S25

Chen YF, Jobanputra P, Barton P, Bryan S et al (2008) Cyclooxygenase-2 selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (etodolac, meloxicam, celecoxib, rofecoxib, etoricoxib, valdecoxib and lumiracoxib) for osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess (Winchester, England) 12(11):1–278

Lories RJ (2012) Etoricoxib and the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 8(12):1599–1608

Leclercq P, Malaise MG (2004) Etoricoxib (arcoxia). Rev Med Liege 59(5):345–349

Disclosures

None.

Author contributions

The intent of this statement is to display our idea on acute gout. SZ and JW conceived and designed the experiments. All authors participated in the literature search, assessment of bias, and data analysis. Data extraction was performed by SZ and checked by JW. SZ wrote the paper and PL made modifications.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, S., Zhang, Y., Liu, P. et al. Efficacy and safety of etoricoxib compared with NSAIDs in acute gout: a systematic review and a meta-analysis. Clin Rheumatol 35, 151–158 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-015-2991-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-015-2991-1