Abstract

The pediatric syndrome characterized by periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and cervical adenitis (PFAPA) and adult Behçet’s disease share some clinical manifestations and are both polygenic autoinflammatory disorders with interleukin-1β showing to play a pivotal role. However, the diagnosis is mostly clinical and we hypothesize that specific criteria may be addressed differently by different physicians. To determine the diagnostic variability, we compared the answers of 80 patients with a definite diagnosis of Behçet’s disease (age 42.1 ± 13.7 years) obtained by separate telephone interviews conducted by a rheumatologist, a pediatrician, and an internist working largely in the field of autoinflammatory disorders. Questions were related to the age of symptom onset, the occurrence of recurrent fevers during childhood, and the association with oral aphthosis, cervical adenitis and/or pharyngitis, previous treatments, possible growth impairment, the time lapse between PFAPA-like symptoms and the onset of Behçet’s disease, and the occurrence of Behçet-related manifestation during childhood. The rheumatologist identified 30 % of patients with Behçet’s disease fulfilling PFAPA syndrome diagnostic criteria, compared to the pediatrician and the internist identifying 10 and 7.5 %, respectively. Most of the patients suffered from recurrent oral aphthosis in childhood also without fever (50, 39, and 48 % with each interviewer), yet no patient fulfilled the Behçet’s disease diagnostic criteria. Our data suggest that physician awareness and expertise are central to the diagnosis of autoinflammatory disorders through an accurate collection of the medical history.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and cervical adenitis (PFAPA) syndrome was first defined in 1987 [1] as a non-inherited autoinflammatory disorder [2] in which interleukin (IL)-1β has a central role [3, 4]. This syndrome generally appears before the age of 5 and is characterized by recurrent fever lasting 3–6 days, with a dramatic response to corticosteroids [5, 6], but is not exceptional at older ages [7, 8]. The diagnosis of PFAPA syndrome requires the exclusion of other diseases (i.e., infections, immune deficiency, malignancy, autoimmune, or monogenic autoinflammatory disorders) and is based on the presence of recurrent fever and at least one sign among aphthosis, pharyngitis, and cervical adenitis in the absence of cyclic neutropenia and upper respiratory tract infections. Young patients are asymptomatic between flares and manifest no developmental delay [9].

Behçet’s disease (BD) is a chronic inflammatory disorder, characterized by relapsing oral and genital ulcers, skin lesions, and uveitis, while other manifestations may include arthritis, positive pathergy test, thrombophlebitis, central nervous system disease, and gastrointestinal signs. Life-threatening BD manifestations are rare, but mortality is secondary to serious vascular-thrombotic and neurological manifestations, and treatments are empirical. However, BD has recently been considered at the crossroad between autoimmune and autoinflammatory disorders [10] and IL-1β inhibition represents an effective treatment strategy [11–14].

Since PFAPA syndrome and BD share pathogenetic and clinical features [3, 4, 15, 16] we hypothesized that patients diagnosed with BD during adulthood might have manifested symptoms consistent with PFAPA syndrome during childhood and compared the capacity of three physicians to inquire about the consistent medical history.

Patients and methods

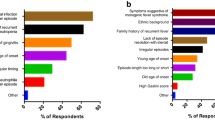

Interviews were conducted on 80 patients with BD (Table 1) attending our Rheumatology Units by telephone separately by a rheumatologist, a pediatrician, and an internist experienced in autoinflammatory disorders. In all cases, interviews followed the same order, with the rheumatologist being the first to conduct the interviews. Questions were pre-arranged (Table 2) and included the occurrence of recurrent febrile attacks during childhood. Subjects with fever flares during childhood were also asked (i) if fever attacks were accompanied by oral aphthosis and/or cervical adenitis and/or pharyngitis, best if negative throat swab cultures were available; (ii) the age at disease onset, mean duration, and frequency of febrile attacks; (iii) therapies performed during fevers and clinical response to antibiotics, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), or corticosteroids; (iv) symptoms between PFAPA-like attacks; (v) growth impairment or delay; (vi) the time in years between PFAPA-like signs resolution and BD onset, and (vii) any further BD manifestation during childhood. The diagnostic Marshall criteria for PFAPA syndrome modified by Thomas et al. [3, 4] and the International Study Group (ISG) criteria for the diagnosis of BD [17] were applied to the answers obtained during the phone interviews to estimate the prevalence of positive results by both criteria during childhood.

Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± SD and normal distributions were evaluated by the Anderson-Darling test. For comparisons of data obtained during telephone interviews, the ANOVA or Kruskall-Wallis tests were used for continuous variables and χ 2 test for categorical variables. Pairwise comparisons were performed using the Fisher exact test, with Bonferroni correction. Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) was used for statistical computations.

Results

Applying Marshall criteria to phone interviews by a rheumatologist, 24 out of 80 (30 %) BD cases also fulfilled the diagnosis of PFAPA syndrome in childhood. When a pediatrician and an internist with expertise in autoinflammatory disorders contacted the same patients, the 10 and 7.5 % of patients fulfilled Marshall criteria, respectively. In all three interviews, however, none of the patients could be diagnosed with BD during childhood. Table 1 illustrates the demographic, genetic, and clinical features of BD cases enrolled in the present study, while Table 3 summarizes clinical features of patients complaining PFAPA-consistent signs during childhood.

The rheumatologist further identified two additional cases with a fever of unknown origin (FUO) inconclusive for PFAPA during childhood, while the internist experienced in the field of autoinflammatory disorders identified five patients with FUO. The pediatrician identified no FUO occurrence. Conversely, the pediatrician identified 34 % of BD cases with a childhood history of oral aphthosis during fevers, while only 20 and 16 % of cases manifested this finding when interviewed by the rheumatologist and the internist, respectively (P = 0.017). Oral aphthosis unrelated to fever was reported by 50 % of cases to the rheumatologist, 39 % to the pediatrician, and 48 % to the internist with expertise in the autoinflammatory disorders. Genital aphthosis was referred by six BD patients to any of the three physicians conducting the interview.

The number of patients reporting a complete response to NSAIDs and antibiotics during fever attacks differed significantly among the three sets of interview to antibiotics (33.33 % of cases to the rheumatologist, 84.78 % to the pediatrician, and 67.56 % to the internist with expertise in autoinflammatory disorders; P < 0.001) or NSAIDs (57.14 % of cases to the rheumatologist, 83.33 % to the pediatrician, and 46.15 % to the internist with expertise in autoinflammatory disorders; P = 0.044).

Discussion

BD and PFAPA syndrome share different clinical manifestations, and both disorders show a marked cytokine secretion disruption with IL-1β playing a key pathogenetic role [3, 4, 15, 16, 18], albeit in different age groups. Triggering infectious factors are supposed to participate in the outbreak of BD in genetically predisposed subjects [19], and even a peculiar dysbiosis of the gut microbiota might be involved in the differentiation of T-regulatory cells of BD patients [20]. On the other hand, the role of infections in PFAPA syndrome has not yet been elucidated, and many authors question the existence of unambiguous microbiologic etiology [21].

In the present study, we hypothesized that BD patients could fulfill PFAPA syndrome criteria during childhood and observed that this was the case in 7.5–30 % of patients with BD, depending on the physician conducting the survey, with the lowest prevalence for the physician experienced in the field of autoinflammatory disorders. All physicians were unaware of the study results and utilized the same questions and criteria, thus suggesting that discrepancies were likely due to different ways of asking questions and interpreting answers. We are particularly intrigued by the similar data obtained by the pediatrician and the internist experienced in the field of autoinflammatory disorders, while the rheumatologist may have a different sensitivity for childhood manifestations. In addition, since the rheumatologist was the less confident with FUO, our findings are in agreement with many previous experiences suggesting that autoinflammatory disorders should be evaluated and ascertained on the basis of expertise [22, 23].

Of note, the questions regarding the presence of oral aphthosis in association with fever during childhood demonstrated the largest variability among the three sets of interviews, while statistically significant differences were identified also for the rates of complete response to NSAIDs and antibiotics during fever attacks. This likely implies a different interpretation by the three medical figures of what constitutes a complete clinical response to therapy, though we cannot rule out that patients may have re-evaluated their responses between interviews providing different answers to the following phone dialogues.

Although most patients suffered from recurrent oral aphthosis, no patient fulfilled the criteria for the diagnosis of BD during childhood [17]. In addition, since oral aphthosis has been reported as the presenting symptom in most BD patients [24], we investigated whether there was a continuity between PFAPA-related manifestations and BD clinical features. In this regard, the average number of years between resolution of PFAPA signs and the onset of BD manifestations was unclear, as most patients could not recollect when the PFAPA clinical signs completely disappeared. However, all patients with PFAPA-related symptoms and signs stated that a certain time had passed between child and adult clinical manifestations. We may surmise that the same disease-causing cytokine alterations can occur as PFAPA syndrome during childhood and as BD during adulthood.

In conclusion, we report herein that the discrimination between PFAPA syndrome during childhood and BD may be arduous and that exact recognition of each condition depends on the expertise of the physician. We observed that a large proportion of patients fulfilled Marshall criteria in all three sets of interviews, suggesting either that a common immune imbalance might underlie both diseases or that PFAPA cytokine derangement might prepare or precede BD in such predisposed patients. However, since the power of Marshall diagnostic criteria is rather limited, we expect that more accurate and validated criteria for the clinical diagnosis of PFAPA syndrome will be developed in the future [25], along with definition of new laboratory, clinical and epidemiologic data related to this condition.

References

Marshall GS, Edwards KM, Butler J, Lawton AR (1987) Syndrome of periodic fever, pharyngitis, and aphthous stomatitis. J Pediatr 110:43–46

Rigante D (2012) The fresco of autoinflammatory diseases from the pediatric perspective. Autoimmun Rev 11:348–356

Stojanov S, Lapidus S, Chitkara P et al (2011) Periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and adenitis (PFAPA) is a disorder of innate immunity and Th1 activation responsive to IL-1 blockade. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:7148–7153

Kolly L, Busso N, von Scheven-Gete A et al (2013) Periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, cervical adenitis syndrome is linked to dysregulated monocyte IL-1β production. J Allergy Clin Immunol 131:1635–1643

Marshall GS, Edwards KM, Lawton AR (1989) PFAPA syndrome. Pediatr Infect Dis J 8:658–659

Thomas KT, Feder HM Jr, Lawton AR, Edwards KM (1999) Periodic fever syndrome in children. J Pediatr 135:15–21

Cantarini L, Vitale A, Bartolomei B, Galeazzi M, Rigante D (2012) Diagnosis of PFAPA syndrome applied to a cohort of 17 adults with unexplained recurrent fevers. Clin Exp Rheumatol 30:269–271

Padeh S, Stoffman N, Berkun Y (2008) Periodic fever accompanied by aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis and cervical adenitis syndrome (PFAPA syndrome) in adults. Isr Med Assoc J 10:358–360

Padeh S, Brezniak N, Zemer D et al (1999) Periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and adenopathy syndrome: clinical characteristics and outcome. J Pediatr 135:98–101

Gül A (2005) Behçet's disease as an autoinflammatory disorder. Curr Drug Targets Inflamm Allergy 4:81–83

Gül A, Tugal-Tutkun I, Dinarello CA et al (2012) Interleukin-1β-regulating antibody XOMA 052 (gevokizumab) in the treatment of acute exacerbations of resistant uveitis of Behçet's disease: an open-label pilot study. Ann Rheum Dis 71:563–566

Cantarini L, Vitale A, Borri M, Galeazzi M, Franceschini R (2012) Successful use of canakinumab in a patient with resistant Behçet's disease. Clin Exp Rheumatol 30:S115

Vitale A, Rigante D, Caso F et al (2014) Inhibition of interleukin-1 by canakinumab as a successful mono-drug strategy for the treatment of refractory Behçet's disease: a case series. Dermatology 228:211–214

Cantarini L, Vitale A, Scalini P, Dinarello CA, Rigante D, Franceschini R et al (2013) Anakinra treatment in drug-resistant Behçet's disease: a case series. Clin Rheumatol. doi:10.1007/s10067-013-2443-8

Yosipovitch G, Shohat B, Bshara J, Wysenbeek A, Weinberger A (1995) Elevated serum interleukin 1 receptors and interleukin 1B in patients with Behçet's disease: correlations with disease activity and severity. Isr J Med Sci 31:345–348

Zou J, Guan JL (2014) Interleukin-1-related genes polymorphisms in Turkish patients with Behçet disease: a meta-analysis. Mod Rheumatol 24:321–326

International Study Group for Behçet disease (1990) Criteria for diagnosis of Behçet’s disease. Lancet 335:1078–1080

Zhou ZY, Chen SL, Shen N, Lu Y (2012) Cytokines and Behçet's disease. Autoimmun Rev 11:699–704

Pineton de Chambrun M, Wechsler B, Geri G et al (2012) New insights into the pathogenesis of Behcet's disease. Autoimmun Rev 11:687–698

Consolandi C, Turroni S, Emmi G et al (2014) Behçet's syndrome patients exhibit specific microbiome signature. Autoimun Rev. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2014.11.009

Esposito S, Bianchini S, Fattizzo M et al (2014) The enigma of periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis and adenitis syndrome. Pediatr Infect Dis J 33:650–652

Federici L, Rittore-Domingo C, Koné-Paut I et al (2006) A decision tree for genetic diagnosis of hereditary periodic fever in unselected patients. Ann Rheum Dis 65:1427–1432

Cantarini L, Vitale A, Lucherini OM et al (2014) The labyrinth of autoinflammatory disorders: a snapshot on the activity of a third-level center in Italy. Clin Rheumatol. doi:10.1007/s10067-014-2721-0

Davatchi F, Shahram F, Chams-Davatchi C et al (2010) Behçet’s disease in Iran: analysis of 6500 cases. Int J Rheum Dis 13:367–373

Hofer M, Pillet P, Cochard MM et al (2014) International periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, cervical adenitis syndrome cohort: description of distinct phenotypes in 301 patients. Rheumatology (Oxford) 53:1125–1129

Conflict of interest

None

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Luca Cantarini, Antonio Vitale, Carlo Selmi, and Donato Rigante equally contributed to the work.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cantarini, L., Vitale, A., Bersani, G. et al. PFAPA syndrome and Behçet’s disease: a comparison of two medical entities based on the clinical interviews performed by three different specialists. Clin Rheumatol 35, 501–505 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-015-2890-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-015-2890-5