Abstract

Takayasu’s arteritis (TA) is a rare granulomatous vasculitic disease that affects the aorta and its major branches. Recent studies have suggested that anti-TNFα biological therapies are highly effective in treating TA refractory to conventional immunosuppressive therapy. We describe two patients with TA: one with progressive TA despite management with two different anti-TNFα agents, infliximab and adalimumab, and another who developed TA while treated with infliximab for the management of pre-existing Crohn’s disease. From our observations, we believe that a multicentered randomized study should be designed to assess the extent of resistance to these agents when different therapeutic doses are employed for managing TA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

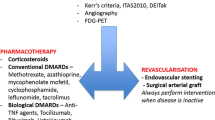

Takayasu’s arteritis (TA) is a rare form of granulomatous arteritis that affects the aorta and its major branches. The pathophysiology of TA is not clear; however, it is believed to be mediated by a cell-mediated autoimmune disease process. We describe two cases of patients, one with existing Crohn’s disease (CD), who were on anti-TNFα agents and either developed or showed progression of Takayasu’s arteritis. Several authors have reported an association between CD and TA, as the probability of CD occurring in a patient with TA is much higher (9%) [1, 2] than if by chance. Recently, the use of anti-TNF biological agents has been employed in treating patients with CD or TA not responsive to standard immunosuppressive therapy. These agents neutralize soluble, and/or membrane-bound TNFα, and thereby inhibit its many biological activities (e.g., synthesis of inflammatory cytokines/chemokines, increased lymphocyte homing and trafficking, increased macrophage activation/survival, etc.) [3]. Among these agents, infliximab (IFX, Remicade, Centocor Inc., Horsham, PA, USA) has been most extensively studied, followed by adalimumab (Humira, Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL, USA). IFX is a chimeric monoclonal antibody composed of the human IgG1 constant region (Fc) fused with the murine variable region recognizing TNFα, while adalimumab has a similar composition but is fully humanized [3]. Here, we describe two patients with very different profiles but a shared diagnosis of TA and treated with IFX then adalimumab or IFX alone without remission of their disease.

Case 1

A 39-year-old G2P2A0 Caucasian female patient presented with a 2-year history of exertional dyspnea, chest pain, and progressive fatigue. The patient described symptoms of bilateral lower limb claudication, and weakness in the right upper extremity. Her past medical history was significant for Hashimoto’s thyroiditis treated with a total thyroidectomy, and mild aortic stenosis with a bicuspid aortic valve. On examination, she had a slightly weaker right radial pulse, and normal carotid pulses. Her blood pressure in her right arm was 130/70 and 150/80 in the left arm. A systolic ejection murmur (2/6) radiating to the subclavian and carotid regions was also noted. No abdominal/femoral bruits, or abdominal/renal masses were detected. Laboratory investigations were normal—hemoglobin (Hg) 124 g/L, MCV 79 fL. Her ESR was slightly elevated (23 mm/h—normal 0–15). A transesophageal echocardiogram suggested a concentric thickening of the ascending aorta without dilation pattern. Subsequent computed tomography (CT) demonstrated thickening of the ascending aorta with extension into the arch of the aorta, right brachiocephalic, right and common carotid branches, and left subclavian arteries. In addition, edema and contrast enhancement were evident in areas of wall thickening (data not shown). There was no evidence of stenosis in any of these branches, or involvement of the descending, or the abdominal aorta. Together, these findings were highly suggestive of type I TA.

She was treated with high-dose systemic corticosteroids (60 mg/day for 4 weeks, and 40 mg/day for 2 weeks). After the course of prednisone, a follow-up MRI demonstrated the resolution of edema in her large arterial vessels. Approximately 4 months later, she developed chest pain and exertional dyspnea. Consequently, she was treated with another course of corticosteroids. However, she developed osteopenia, and her prednisone dose was tapered, and methotrexate (15 mg/week orally) with folate (5 mg/day) were introduced. During the gradual decrease of her steroid therapy, she developed left ear and left hand pain, and increasing fatigability. In addition, her systolic murmur also increased in severity (grade 4/6). As a result, systemic steroids were reintroduced (60 mg/day) until azathioprine was started, while MTX was discontinued. When azathioprine therapy was commenced, she developed severe abdominal pain. Consequently, it was discontinued and high-dose prednisone was used instead. Approximately 3 months later, IFX (3 mg/kg) with MTX (15 mg/week) were used to treat her TA. Her disease was in complete remission for almost 5 months, but it relapsed as suggested by episodes of fatigability, and with a follow-up MRI (Fig. 1a) suggesting active inflammation in her arteries. Thus, anti-TNF therapy was changed from IFX to adalimumab which was effective in controlling the disease process for a short period before it relapsed again (Fig. 1b). Currently, her disease is in remission on cyclophosphamide.

Case 2

A 17-year-old African-American girl with an 18-month history of CD characterized by significant perianal disease, presented to the emergency room with headache, photophobia, oral ulcers, anterior chest pain, abdominal pain, and vomiting. The patient described a 1-week history of bilateral calf pain walking short distances. Her medications included infliximab (3 mg/kg every 8 weeks; for Crohn’s disease), prednisone 20 mg/day, lansoprazole, ciprofloxacin, 5-aminosalicylic acid, and vitamins A, B, C, and D supplements with calcium. Her last CD flare-up was 7 months prior to this episode. On examination, her blood pressure in her right arm was 110/60. She had normal carotid and upper extremity pulses, but the pulses in her lower extremity were not palpable (femoral, popliteal, posterior tibialis, or dorsalis pedis pulses). Blood pressure measurements in the lower limbs could not be obtained. Her abdomen was diffusely tender and she did not tolerate deep palpation. Laboratory investigations demonstrated a microcytic anemia (Hg 94 g/L, MCV 70), with mildly elevated liver enzymes, and significantly elevated inflammatory markers—ESR over 140 mm/h (normal 0–20) and C-reactive protein 143 mg/L (normal 0–8).

CT (Fig. 2a) scan of her abdomen and pelvis revealed mild aortic thickening and inflammatory changes in the retroperitoneal fat involving the upper abdominal aorta, infrarenal aorta with significant inflammation at the origins of the renal arteries. In addition, the proximal renal arteries and the bilateral common femoral arteries demonstrated mild thickening and surrounding inflammatory changes. There was no evidence of stenosis or aneurysms in the aorta or its branches within the neck, chest, or abdomen. However, wall thickening was noted in the proximal abdominal aorta extending from the levels of the diaphragm to the level of the renal arteries with extension into the celiac, superior mesenteric, left renal arteries and right common femoral artery—establishing a new diagnosis of Takayasu’s arteritis (Fig. 2b). After developing TA despite her treatment with IFX for her CD, she was switched to methotrexate (25 mg/week, SC injection) to induce remission, and received a corticosteroid bolus. Currently, she does not have any active disease on prednisone 20 mg/day, which is tapering. Her inflammatory markers remain elevated due to on-going activity of her Crohn’s disease.

Conclusion

In this report, we describe two patients who developed active TA despite being treated with anti-TNF biological therapies. Recent studies have suggested that TA refractory to conventional immunotherapy is more responsive to anti-TNF agents [3–6]. In a recent retrospective study by Molloy et al., 21 patients with active relapsing TA not responsive to non-biologic immunosuppressive therapy were treated with IFX for a median of 28 months [5]. A majority (over 70%) either developed complete or partial remission within this time frame using the standard dose of 3 mg/kg. However, the disease relapsed in a large proportion of these patients, and remission was only possible with a larger (5 mg/kg) and more frequent dose of IFX, reflecting a possible reduction in the efficacy of IFX in these patients.

Studies of patients using IFX in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) have supported the hypothesis of blocking antibodies to the drug. In RA, the clinical efficacy of IFX is directly correlated with the development of anti-IFX antibodies which result in lower concentration of IFX circulating in the serum. The inability of IFX (at 3 mg/kg) in controlling the TA disease process may stem from its clearance from the serum by anti-IFX antibodies; while its increased effectiveness at higher doses may suggest a higher bioavailability both due to the higher amounts used, and/or due to decreased levels of anti-IFX antibodies as a result of the induction of immunological tolerance. RA patients that respond to IFX have higher serum trough levels of IFX compared with patients that poorly respond when the standard 3 mg/kg dose is used in an 8-week period [7]. In addition, treatment with larger dosages of IFX result in lower rates of patients developing anti-IFX antibodies [8]. Moreover, anti-IFX antibodies developed in more than 50% of RA patients treated with IFX (3 mg/kg) within the first year of treatment [9]. Similarly, more than 61% of CD patients also developed anti-IFX antibodies within the first year of therapy [10]. The relapsing nature of the inflammatory process for both of our patients may reflect the loss of IFX efficacy due to anti-IFX antibodies. In fact, the unresponsiveness of our first patient to adalimumab following IFX treatment may also indicate the presence of anti-adalimumab antibodies as recently suggested [11].

The rare association of CD with TA has previously been described by other groups [2, 12–16]. Thirty-two cases have been reported in the literature, and many of the authors have suggested that both diseases may share a common etiology. Unfortunately, there is no clear association between a common HLA genotype that is shared by both diseases. In addition, although Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) has been linked to the pathogenesis of both diseases, there is no direct evidence implicating MTB in the pathogenesis. Pathologically, both diseases are granulomatous in nature with a cell-mediated autoimmune component playing an integral component in their pathogenesis [17, 18].

In summary, we describe two patients that developed active TA inflammation despite being treated with a standard regimen of anti-TNF biologics. Although these agents have been suggested in case–control studies to be highly effective for the treatment of TA refractory compared to conventional immunosuppressive therapy, ideally a multicentered randomized control study may be useful in determining their utility for patients with TA. However, we understand that conducting such a study may be difficult. Caution should be used in TA patients using these agents, as relapse is possible. For patients with TA that relapse on anti-TNF biologics, the dose of these therapies should be revisited, and the development of anti-IFX or anti-adalimumab antibodies should be monitored, if possible, to predict treatment efficacy and the development of resistance.

References

Baumgart DC, Sandborn WJ (2007) Inflammatory bowel disease: clinical aspects and established and evolving therapies. Lancet 369(9573):1641–5167

Reny JL et al (2003) Association of Takayasu’s arteritis and Crohn’s disease: results of a study on 44 Takayasu patients and review of the literature. Ann Med Interne (Paris) 154(2):85–90

Chung SA, Seo P (2009) Advances in the use of biologic agents for the treatment of systemic vasculitis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 21(1):3–9

Maffei S et al (2009) Refractory Takayasu arteritis successfully treated with infliximab. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 13(1):63–65

Molloy ES et al (2008) Anti-tumour necrosis factor therapy in patients with refractory Takayasu arteritis: long-term follow-up. Ann Rheum Dis 67(11):1567–1569

Filocamo G et al (2008) Treatment of Takayasu’s arteritis with tumor necrosis factor antagonists. J Pediatr 153(3):432–434

Wolbink GJ et al (2005) Relationship between serum trough infliximab levels, pretreatment C reactive protein levels, and clinical response to infliximab treatment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 64(5):704–707

St Clair EW et al (2002) The relationship of serum infliximab concentrations to clinical improvement in rheumatoid arthritis: results from ATTRACT, a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 46(6):1451–1459

Wolbink GJ et al (2006) Development of antiinfliximab antibodies and relationship to clinical response in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 54(3):711–715

Baert F et al (2003) Influence of immunogenicity on the long-term efficacy of infliximab in Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med 348(7):601–608

Bartelds GM et al (2010) Anti-infliximab and anti-adalimumab antibodies in relation to response to adalimumab in infliximab switchers and anti-TNF naive patients: a cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis 69(5):817–821

El-Matary W, Persad R (2009) Takayasu’s aortitis and infliximab. J Pediatr 155(1):151

Farrant M et al (2008) Takayasu’s arteritis following Crohn’s disease in a young woman: any evidence for a common pathogenesis? World J Gastroenterol 14(25):4087–4090

Levitsky J, Harrison JR, Cohen RD (2002) Crohn’s disease and Takayasu’s arteritis. J Clin Gastroenterol 34(4):454–456

Owyang C et al (1979) Takayasu’s arteritis in Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 76(4):825–828

Friedman CJ, Tegtmeyer CJ (1979) Crohn’s disease associated with Takayasu’s arteritis. Dig Dis Sci 24(12):954–958

Johnston SL, Lock RJ, Gompels MM (2002) Takayasu arteritis: a review. J Clin Pathol 55(7):481–486

Karlinger K et al (2000) The epidemiology and the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Radiol 35(3):154–167

Disclosures

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Osman, M., Aaron, S., Noga, M. et al. Takayasu’s arteritis progression on anti-TNF biologics: a case series. Clin Rheumatol 30, 703–706 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-010-1658-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-010-1658-1