Abstract

As a measure of healthcare cost containment, the total number of vials of entanercept (25 mg) that can be prescribed for patients with inflammatory arthritis is restricted in Korea. Consequently, attempts to extend the dosing interval while maintaining the efficacy have not been an uncommon clinical practice. The aim of this study was to determine if extended doing interval of etanercept can be effective in patients with ankylosing spondylitis (AS). We performed a retrospective analysis using medical records at a single tertiary hospital. One hundred and nine patients with AS and 79 patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) started on etanercept between November 2004 and November 2009 were indentified. Etanercept (25 mg) was started with twice-weekly dosing schedule. Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI), C-reactive protein (CRP), and etanercept dosing interval for AS patients at 0, 3, 9, 15, 21 months were reviewed. Dosing interval for RA patients was analyzed for comparison. In AS, mean dosing interval was 4.7 ± 2.1 days at 3 months and was increased to 12.1 ± 7.0 days at 21 months. Despite the progressive increase in the dosing interval, the mean BASDAI declined rapidly at 3 months, and continued to decrease over 21 months. Mean CRP declined after 3 months of therapy and remained low thereafter. In RA, mean dosing interval was 4.0 ± 1.2 days at 3 months and 5.1 ± 1.8 days at 21 months. In conclusion, in AS, extended dosing of etanercept can be effective without compromising clinical and laboratory markers of disease activity as measured by BASDAI and CRP, respectively. Tapering of etanercept was less accommodating in RA when compared to AS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is an inflammatory disease characterized by insidious inflammation of the spine, sacroiliac, and peripheral joints. The prevalence varies among ethnic groups and geographic locations, ranging from 0.1% to 1.4% [1, 2]. Until recently, limited pharmacologic options were available for AS. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) relieve joint pain and inflammation temporarily. Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) have shown no benefits in axial manifestations of AS, although sulfasalazine has limited efficacy in peripheral arthritis [3]. The European League Against Rheumatism recommended anti-TNF therapy for AS patients refractory to conventional treatments [4]. The introduction of TNF-antagonists gave major breakthroughs that have improved outcomes in AS patients, and achieving a remission is now a reasonable treatment objective [5–7]. However, no guidelines are currently available on when to stop or how to taper these agents when a good clinical response is reached.

Etanercept, a fusion protein consisting of the extracellular portion of a human TNFR-75 fused to the Fc portion of human IgG subclass I molecule, has demonstrated significant efficacy and a favorable safety profile in patients with active AS [7–10]. As a healthcare cost containment measure due to its high cost, the Korean National Healthcare Insurance Policy restricted the total number of vials of entanercept (25 mg) that can be prescribed to patient with AS and rheumatoid arthritis (RA). As a consequence, attempts in extending the dosing interval in order to prolong the overall treatment duration, while maintaining the efficacy, have not been an uncommon clinical practice in Korea. Ironically, this rather discouraging situation has provided an ideal opportunity to observe if tapering of etanercept is achievable. Thus, the aim of this study was to determine if extended dosing of etanercept can be effective in patients with AS and RA without compromising clinical disease activity. In the present study, we describe our clinical efficacy data with etanercept over the observation period of 21 months and demonstrate that extended dosing of etanercept 25 mg can be effective in patients with AS.

Materials and methods

We performed a retrospective analysis using medical records at a single tertiary hospital. Patients with AS and RA, defined by the modified New York criteria [11] and ACR criteria [12], respectively, who were initiated on etanercept therapy between November 2004 and November 2009 were included in the study. To be eligible for TNF-α antagonist therapy according to the Korean National Health Insurance Policy, AS patients have to fulfill the following criteria: high disease activity (Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) higher than 4), radiographic evidence of sacroiliitis (grade ≥2 bilaterally or ≥3 unilaterally), and failure to respond to NSAIDs or DMARDs therapy of at least three consecutive months. Three months after initiation of etanercept, BASDAI reduction of at least 50% or absolute decrease of more than 2 units (0–10 scale) has to be documented in order for the treatment to continue. BASDAI measurement every 6 months thereafter is also required and must demonstrate the same degree of efficacy as initial measurements at 3 months. For RA patients, the following criteria needs to be satisfied: erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) > 28 mm/hr or C-reactive protein (CRP) > 2.0 mg/dL, morning stiffness of more than 45 min, total number of tender or swollen joint count >20 (more than six if at least four of following large joints are involved: elbow, wrist, knee, ankle, shoulder and hip), failure of 6-months therapy with at least two DMARDs including methotrexate due to inefficacy or side effects. At 3-months follow-up visit, ESR < 28 mm/hr or CRP < 2 mg/dL, or 20% reduction in either of these parameters, and 50% reduction in tender of swollen joint count need to be demonstrated for continuation of therapy. These measurements need to be repeated every 6 months thereafter and must satisfy the same degree of efficacy as 3-months visit. The Korean National Health Insurance Policy mandates that the total number of vials of etanercept allowed for each patient with AS and RA are 417 and 442, respectively. The patients are required to pay out-of-pocket for any additional vials once these limits are reached.

Medical records were reviewed for baseline demographic data, clinical characteristics including laboratory data, BASDAI [13] in AS patients, and dosing interval at 3, 9, 15, 21 months after starting etanercept. All patients were pre-screened for latent tuberculosis infection by history, chest radiograph, and purified protein derivative skin test. Based on the objective clinical assessment and subjective improvement reported by the patients at each visit (every month), the dosing interval was increased in a stepwise fashion; twice-weekly to every 5 days, then every 7, 9, 11 and 13 days. Should a patient discontinue treatment, the main reason is also recorded. Etanercept 25 mg was started at twice-weekly schedule for all AS and RA patients. Only 25-mg vials of etanercept is currently available in Korea.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as means and standard deviation and as percentages. To compare continuous variable distributions, Wilcoxon signed-rank test was performed. Differences were considered significant at the p < 0.05 levels. The Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (version 4.0, San Diego, CA, USA).

Results

Baseline characteristics

In total, 109 AS and 79 RA patients who were started on etanercept (25 mg) with variable duration of therapy were analyzed. The demographic data of AS and RA patients before the start of etanercept are illustrated in Table 1.

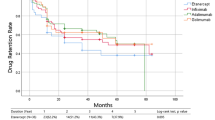

Efficacy and dosing interval of etanercept

Etanercept (25 mg) was started with twice-weekly dosing schedule. In AS patients, the mean dosing interval gradually increased to 4.7 ± 2.1 days at 3 months, 8.5 ± 4.9 days at 9 months, 9.9 ± 5.8 days at 15 months, and 12.1 ± 7.0 days at 21 months (Table 2). Mean BASDAI was 8.5 ± 1.3 at 0 month and decreased rapidly to 2.29 ± 1.4 at 3 months (p < 0.0001), and continued downward to 1.6 ± 1.4 at 9 months, 1.0 ± 0.9 at 15 months, and 0.6 ± 0.7 at 21 months. Mean CRP was 3.7 ± 4.1 mg/dL at 0 month and decreased promptly to 0.6 ± 1.3 mg/dL at 3 months and remained low at 0.6 ± 1.1 mg/dL at 9 months, 0.5 ± 0.9 mg/dL at 15 months, and 0.6 ± 0.6 mg/dL at 21 months. Despite the progressive increase in the dosing interval, mean BASDAI scores declined gradually at 3, 9, 15, and 21 months (Fig. 1a). Furthermore, mean CRP declined after 3 months of therapy (p < 0.0001) and remained low at 9, 15, and 21 months. In RA patients, mean dosing interval increased to 4.0 ± 1.2 days at 3 months, 4.8 ± 1.7 days at 9 months, 5.1 ± 1.9 days at 15 months, and 5.1 ± 1.8 days at 21 months (Table 2). As compared to AS patients, the increase in the dosing interval in RA was less robust (Fig. 1b). During the course of observation, one patient with AS discontinued etanercept due to secondary failure at 2 months, while four patients with RA switched to another TNF-α antagonist (two primary failures at 0.8 and 1.9 months, and two secondary failures at 2 and 15.9 months). At 21 months follow up, etanercept survival rate in AS and RA patients were 98% and 84%, respectively. The proportion of patients remained on twice-weekly dosing at 3, 9, 15, and 21 months were 67.6%, 29.4%, 6.7%, and 6.3% for AS, respectively, and 88.5%, 57.1%, 50.0%, and 47.6% for RA, respectively (Table 3).

Discussion

In this retrospective observational cohort study, we demonstrated that extended dosing of etanercept can be effective in AS and RA patients. The government cost containment efforts in healthcare produced a prescription pattern of etanercept that is deviated from the standard practice, thus providing an ideal opportunity for this study.

Etanercept has demonstrated rapid and consistent effectiveness in reducing the axial and peripheral symptoms of AS and improving patient function and quality of life (QOL) [7, 14]. Etanercept is administered by subcutaneous self-injection, usually in a 50 mg once-a-week, or 25 mg twice-a-week dosing interval. Patients with AS can expect a comparable significant improvement in clinical outcomes with similar safety when treated with etanercept 50 mg once-weekly or with 25 mg twice-weekly [15]. No significant differences in the pharmacokinetic exposure between the two etanercept regimens were found [15]. Improvement in function and QOL were reported to be similar in these dosing regimens [16]. Unfortunately, there exists no evidence for the inhibition of structural progression of spine disease in AS patients treated with etanercept for nearly 2 years [17]. Therefore, if the main goal of starting etanercept is to improve symptoms, function and the QOL, it stands to reason that clinicians may attempt to increase the dosing interval of etanercept as long as aforementioned parameters are not compromised. Furthermore, considering the fact that the potential cost–effectiveness of etanercept in patient with severe AS has been demonstrated [18], further cost reduction may be achieved by incorporating the result of our data in daily clinical practice.

This study is the first to evaluate the gradual tapering of etanercept in patients with AS and RA while maintaining its efficacy. A previous study involving RA patients with remission on etanercept have investigated the duration until disease relapse after discontinuing etanercept and the efficacy with readministration in those who relapsed [19]. Fifty percent of patients were on half-dose therapy (25 mg/week) at the time of discontinuation and found no difference in the time to relapse between the group on full-dose and the group on half-dose etanercept therapy before discontinuation. This result indirectly implies that dose reduction of etanercept can be feasible in those with clinical remission. Despite the fact that the dosing interval of etanercept in RA group from our study did not reach once-weekly dosing at 21 months (5.1 ± 1.8 days), it seems reasonable to assume that a dosage reduction or extending dosing interval can be an effective therapeutic approach before drug discontinuation.

Dose reduction of etanercept from 50 mg once-weekly to maintenance dose of 25 mg once-weekly have been investigated in a small number of AS patients and reported that 25 mg given weekly is effective enough to maintain remission [20]. However, after the initial 3-months therapy with etanercept 50 mg/week, six out of 23 patients (26.1%) were dropped out during the maintenance period with 25 mg/week, one patient due to disease flare, and five patients were lost to follow up. This high drop-out rate makes the final results difficult to interpret. On that account, rather than abrupt dose reduction of etanercept, a gradual tapering would be more preferable and may help facilitate the smooth transition into the lowest effective dose of etanercept.

Our study demonstrated that tapering of etanercept is much less accommodating in RA patients compared to AS patients, presumably due to higher efficacy of etanercept in AS patients. Accordingly, etanercept continuation rate in AS patients was also higher than RA patients (98% vs. 84%, respectively) at 21 months, due to less loss of efficacy. This is inconsistent with previous finding from an observational study where the continuation rate of etanercept after 1 year was higher in RA compared to spondyloarthropathy (SpA) patients including AS patients (87% vs. 76%) [21]. However, when all TNF-α antagonists were included, overall drug survival rate was better in SpA than in RA [22].

The significance of the present study lies in several aspects. First, extended dosing interval of etanercept may create considerable cost containment in healthcare system with financial strain. Second, possible side effects of etanercept therapy including the risk of infection may be considerably dampened with reduced drug exposure. Lastly, less frequent self-injection may escalate compliance and drug adherence. Our study included patients with severe refractory disease despite of ongoing treatment with combination of DMARDs and NSAIDs. Hence, the implication of our study may also be extended to patients with less severe disease activity before the start of etanercept, and further tapering may be achieved.

Our study is limited due to the retrospective observation without control group of patients who adhered to the standard dosing schedule. Nevertheless, our study opens a novel pathway of therapeutic approach in prescribing etanercept for patients with AS and RA. The potential benefits of tapering etanercept over conventional standard dosing regimen need to be investigated further in a prospective randomized trial in the future.

In conclusion, the efficacy of etanercept can be maintained despite the increase in dosing interval in patients with AS and RA. Tapering of etanercept was less accommodating in RA when compared to AS.

References

Braun J, Bollow M, Remlinger G, Eggens U, Rudwaleit M, Distler A, Sieper J (1998) Prevalence of spondylarthropathies in HLA-B27 positive and negative blood donors. Arthritis Rheum 41:58–67

Gran JT, Husby G, Hordvik M (1985) Prevalence of ankylosing spondylitis in males and females in a young middle-aged population of Tromso, northern Norway. Ann Rheum Dis 44:359–367

Clegg DO, Reda DJ, Abdellatif M (1999) Comparison of sulfasalazine and placebo for the treatment of axial and peripheral articular manifestations of the seronegative spondylarthropathies: a Department of Veterans Affairs cooperative study. Arthritis Rheum 42:2325–2329

Zochling J, van der Heijde D, Burgos-Vargas R, Collantes E, Davis JC Jr, Dijkmans B, Dougados M, Geher P, Inman RD, Khan MA, Kvien TK, Leirisalo-Repo M, Olivieri I, Pavelka K, Sieper J, Stucki G, Sturrock RD, van der Linden S, Wendling D, Bohm H, van Royen BJ, Braun J (2006) ASAS/EULAR recommendations for the management of ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 65:442–452

Braun J, Baraliakos X, Brandt J, Listing J, Zink A, Alten R, Burmester G, Gromnica-Ihle E, Kellner H, Schneider M, Sorensen H, Zeidler H, Sieper J (2005) Persistent clinical response to the anti-TNF-alpha antibody infliximab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis over 3 years. Rheumatology (Oxford) 44:670–676

van der Heijde D, Kivitz A, Schiff MH, Sieper J, Dijkmans BA, Braun J, Dougados M, Reveille JD, Wong RL, Kupper H, Davis JC Jr (2006) Efficacy and safety of adalimumab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 54:2136–2146

Davis JC Jr, Van Der Heijde D, Braun J, Dougados M, Cush J, Clegg DO, Kivitz A, Fleischmann R, Inman R, Tsuji W (2003) Recombinant human tumor necrosis factor receptor (etanercept) for treating ankylosing spondylitis: a randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 48:3230–3236

Calin A, Dijkmans BA, Emery P, Hakala M, Kalden J, Leirisalo-Repo M, Mola EM, Salvarani C, Sanmarti R, Sany J, Sibilia J, Sieper J, van der Linden S, Veys E, Appel AM, Fatenejad S (2004) Outcomes of a multicentre randomised clinical trial of etanercept to treat ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 63:1594–1600

Davis JC Jr, van der Heijde DM, Braun J, Dougados M, Clegg DO, Kivitz AJ, Fleischmann RM, Inman RD, Ni L, Lin SL, Tsuji WH (2008) Efficacy and safety of up to 192 weeks of etanercept therapy in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 67:346–352

Gorman JD, Sack KE, Davis JC Jr (2002) Treatment of ankylosing spondylitis by inhibition of tumor necrosis factor alpha. N Engl J Med 346:1349–1356

van der Linden S, Valkenburg HA, Cats A (1984) Evaluation of diagnostic criteria for ankylosing spondylitis. A proposal for modification of the New York criteria. Arthritis Rheum 27:361–368

Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS, Healey LA, Kaplan SR, Liang MH, Luthra HS et al (1988) The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 31:315–324

Garrett S, Jenkinson T, Kennedy LG, Whitelock H, Gaisford P, Calin A (1994) A new approach to defining disease status in ankylosing spondylitis: the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index. J Rheumatol 21:2286–2291

Brandt J, Listing J, Haibel H, Sorensen H, Schwebig A, Rudwaleit M, Sieper J, Braun J (2005) Long-term efficacy and safety of etanercept after readministration in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 44:342–348

van der Heijde D, Da Silva JC, Dougados M, Geher P, van der Horst-Bruinsma I, Juanola X, Olivieri I, Raeman F, Settas L, Sieper J, Szechinski J, Walker D, Boussuge MP, Wajdula JS, Paolozzi L, Fatenejad S (2006) Etanercept 50 mg once weekly is as effective as 25 mg twice weekly in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 65:1572–1577

Braun J, McHugh N, Singh A, Wajdula JS, Sato R (2007) Improvement in patient-reported outcomes for patients with ankylosing spondylitis treated with etanercept 50 mg once-weekly and 25 mg twice-weekly. Rheumatology (Oxford) 46:999–1004

van der Heijde D, Landewe R, Einstein S, Ory P, Vosse D, Ni L, Lin SL, Tsuji W, Davis JC Jr (2008) Radiographic progression of ankylosing spondylitis after up to two years of treatment with etanercept. Arthritis Rheum 58:1324–1331

Ara RM, Reynolds AV, Conway P (2007) The cost-effectiveness of etanercept in patients with severe ankylosing spondylitis in the UK. Rheumatology (Oxford) 46:1338–1344

Brocq O, Millasseau E, Albert C, Grisot C, Flory P, Roux CH, Euller-Ziegler L (2009) Effect of discontinuing TNFalpha antagonist therapy in patients with remission of rheumatoid arthritis. Joint Bone Spine 76:350–355

Lee SH, Lee YA, Hong SJ, Yang HI (2008) Etanercept 25 mg/week is effective enough to maintain remission for ankylosing spondylitis among Korean patients. Clin Rheumatol 27:179–181

Brocq O, Roux CH, Albert C, Breuil V, Aknouche N, Ruitord S, Mousnier A, Euller-Ziegler L (2007) TNFalpha antagonist continuation rates in 442 patients with inflammatory joint disease. Joint Bone Spine 74:148–154

Carmona L, Gomez-Reino JJ (2006) Survival of TNF antagonists in spondylarthritis is better than in rheumatoid arthritis. Data from the Spanish registry BIOBADASER. Arthritis Res Ther 8:R72

Ackowledgement

Jaejoon Lee, MD and Jungwon Noh, MD equally contributed to this work.

Disclosures

None

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Jaejoon Lee and Jung-Won Noh contributed equally to this article

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, J., Noh, JW., Hwang, J.W. et al. Extended dosing of etanercept 25 mg can be effective in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a retrospective analysis. Clin Rheumatol 29, 1149–1154 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-010-1542-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-010-1542-z