Abstract

Obesity is a modifiable major cause of morbidity and mortality in the general population, but little is known about the association of obesity and quality of life in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Thus, we set out a study to test the hypothesis that obesity is independently associated with lower quality of life in patients with RA. Three hundred and fifty nine patients with RA underwent an interview, physical exam, and all clinical charts were reviewed. Based on body mass index (BMI), patients were classified as normal (BMI < 25 kg/m2), overweight (BMI = 25–29.9 kg/m2), and obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2). Quality of life was quantified with the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36 (SF-36). Data obtained included demographic variables, extra-articular disease, comorbidities, presence of X-ray erosions, rheumatoid factor, and depression. The association between obesity and quality of life was examined with the use of multiple lineal regression models. One hundred and seventy-two patients (47.9%) had normal BMI, 126 (35.1%) were overweight, and 61 patients (17%) were obese. Obese patients had lower quality of life (30.8 ± 18.1) than overweight patients (43.3 ± 20.1) and patients with normal weight (43.8 ± 22.2), P < 0.001. The association between obesity and impaired quality of life was confirmed with a linear regression model (Coef = −12.9, P < 0.001) and remained significant after adjustment for age, sex, disease activity, extra-articular disease, comorbidities, X-ray erosions, presence of rheumatoid factor, depression, education, and disease duration (Coef = −5.3, P = 0.039). In conclusion, obesity is independently associated with the impaired quality of life in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the general population, obesity is a major cause of morbidity and mortality [1, 2] with an annual estimation of 300,000 premature deaths related to obesity [3]. Also, obesity is associated with high healthcare costs—with at least 92 billion U.S. dollars spent in direct health cost in the USA [3]. The prevalence of obesity is high; 30% of American adults are obese and the prevalence is increasing over time [4].

Obesity is an independent risk factor of serious medical problems such as diabetes [5, 6] and cardiovascular disease [7–9], and affects quality of life adversely, an association that was consistently shown in different populations [10–12]. In addition, obesity is linked to high concentrations of several markers of inflammation such as C-reactive protein (CRP), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α); [13, 14] suggesting that there is a pro-inflammatory state in obese patients.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a common chronic inflammatory disease that affects 0.5% to 1% of the population [15] and is associated with increased mortality rates, physical disability, pain, depression, and impaired health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [16–20]. Patients with RA have decreased quality of life in all domains compared to the scores reported by patients with other chronic diseases [21, 22].

In patients with RA, impaired HRQoL is associated with many disease-related factors such as disease activity, joint damage, extraarticular disease, decreased functional capacity, and depression [16–20, 23, 24]. However, little is known about the relationship between obesity and HRQoL in this patient population. Thus, we set out a study to test the hypothesis that obesity is associated with impaired quality of life and that this association is independent of RA-related factors.

Materials and methods

Patients

Three hundred and fifty-nine consecutive patients, aged 18 years or older who met the 1987 ACR classification criteria for RA [25], and attended the outpatient clinic at the Hospital Nacional Edgardo Rebagliati Martins in Lima (Peru) between January 2005 and April 2006 were enrolled. All patients are part of an ongoing study at the hospital. The Institutional Review Board of the hospital approved the study and all patients gave written informed consent.

Procedures

All patients underwent an interview, physical exam, completed patient questionnaires, and all clinical charts were reviewed. Data collected included age, sex, years of education, duration of disease, presence of extra-articular disease, comorbidities, X-ray erosions, and rheumatoid factor. Disease activity was measured using the disease activity score based on 28 joints [26].

Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as the weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters. Based on the BMI, patients were classified as normal (BMI < 25 kg/m2), overweight (BMI = 25–29.9 kg/m2), and obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2).

Health-related quality of life was quantified with the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36 (SF-36) [23]. The SF-36 is a widely validated generic patient questionnaire [27] that showed to be sensitive to change in a variety of chronic diseases including symptomatic peripheral arterial, [28] chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, [29] hypertension [30], and systemic lupus erythematosus [31]. It includes 36 items covering 8 health concepts (domains): physical functioning, role limitations due to physical problems, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role limitations due to emotional problems, and mental health [32]. Results from each health concept questions are presented in a scale from 0 (poor health) to 100 (good health). Two summary measures were further calculated from the items scores using the procedures recommended by the developers: a physical component score (PCS) and a mental component score (MCS) [33]. Measures of depression were obtained from the (0–3) question included in the multi-dimensional health assessment questionnaire (MDHAQ) [34].

Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics are presented using the means and standard deviations for continuous variables and proportions for categorical variables. Body mass index was correlated with demographic and clinical characteristics with the use of Spearman’s correlations. Health-related quality of life scores were compared among patients with normal weight, overweight, and obese with the use of Kruskal–Wallis tests. Linear regression models were used to examine the independent relationship between BMI categories (independent variable) and total SF-36 score (dependent variable). All covariates (age, sex, disease activity, extra-articular disease, comorbidities, X-ray erosions, presence of rheumatoid factor, depression, education, and disease duration) were chosen a priori based on clinical significance. All analyses used a two-sided significant level of 5% and were performed using the statistical package STATA 9.1.

Results

Patient characteristics

Patients’ mean age was 58 ± 14 years, 87% were female, mean education was 11.4 ± 4.6 years, and mean disease duration was 16.5 ± 10.8 years. Ninety-two percent tested positive for rheumatoid factor. Sixty-one patients had at least 1 comorbid condition, extra-articular disease was reported by 15%, joint damage was observed in 83.2%, their mean DAS28 was 4.9 ± 1.5, and their mean depression score was 2.0 ± 0.9 (Table 1).

One hundred and seventy-two patients (47.9%) had normal BMI, 126 (35.1%) were overweight, and 61 patients (17%) were obese.

BMI and clinical characteristics in patients with RA

BMI was statistically significantly associated with disease activity (rho = 0.13, P = 0.01) and functional capacity (rho = 0.13, P = 0.02), but not with age (P = 0.61), years of education (P = 0.26), pain (P = 0.47), fatigue (P = 0.07), patient global assessment (P = 0.16), and number of comorbidities (P = 0.23).

Quality of life and obesity in patients with RA

Obese patients had lower quality of life (30.8 ± 18.1) than overweight patients (43.3 ± 20.1) and patients with normal weight (43.8 ± 22.2), P < 0.001.

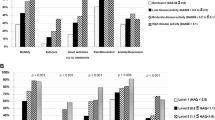

Obese patients also had significant lower scores in both the physical component score (PCS): 29.2 ± 17.2 in obese patients compared to 40.7 ± 20 in overweight patients and 41 ± 21.7 in patients with normal weight, P < 0.001 and the mental component score (MCS): 43.8 ± 22.7 in obese patients compared to 54.6 ± 19.9 in overweight patients and 53.8 ± 22.2 in patients with normal weight, P = 0.004 (Fig. 1).

Obese patients also had significantly lower scores in the four domains of PCS: physical functioning, physical role, bodily pain, and general health compared to overweight and normal weight patients (Table 2).

Obese patients also had significant lower scores in the three domains of the mental component: social functioning, emotional role, and mental health compared to overweight and normal weight patients (P < 0.001, P = 0.002, P = 0.004). There was no statistically significant association between BMI and the vitality domain (P = 0.10) (Table 2).

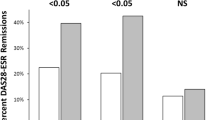

The association between obesity and impaired quality of life was confirmed with a linear regression model (Coef = −12.9, P < 0.001) and remained significant after adjustment for age, sex, disease activity, extra-articular disease, comorbidities, X-ray erosions, presence of rheumatoid factor, depression, education, and disease duration (Coef = −5.3, P = 0.039) (Table 3).

Discussion

This study suggests that RA patients who are obese are more likely to experience impaired quality of life than patients with normal weight, independent of the effect of age, sex, disease activity, extra-articular disease, comorbidities, X-ray erosions, presence of rheumatoid factor, depression, educational level, and disease duration.

Our results showed that obese RA patients have impaired of HRQoL compared to patients who are overweight or have normal weight. The mechanisms underlying this association may include higher levels of disease activity and poorer functional capacity. In concordance with this hypothesis, a recent study of patients with early RA followed-up over a period of 5 years, reported that functional capacity (as measured by the HAQ score) and inflammation (as determined by ESR) were able to predict physical health-related quality of life measured with the Arthritis Impact Measurement Scale 2 [24]. However, the fact that in this study the association between obesity and HRQoL remained significant after adjustment for both disease activity and functional capacity is of interest, especially because obesity is modifiable.

In the general population, reducing obesity improves function and decreases pain. Exercise, dietary modification [35], and weight loss [36] are associated with improved health-related quality of life. Lifestyle changes designed to reduce body weight in obese women decreased the concentrations of inflammatory markers including CRP, IL6, and IL-18, [37], and also implicated in the inflammatory mechanisms of RA.

In other populations, obesity affects the physical more than the mental component of HRQoL [38]. Our findings determined that HRQoL is significantly impaired in obese patients with RA, in both the physical and the mental components. Furthermore, all scores of the four PCS domains were significantly lower among obese patients than in the other groups. However, only three of the four mental domains associated with obesity had significantly lower scores (Table 2).

This study has some limitations. Although a temporal sequence is not determined due to the cross-sectional design; the fact that in other populations some interventions to target obesity also modify quality of life, suggest that impaired quality of life may be attributed, at least in part to obesity. Second, our study did not include patients with low BMI, a group associated with higher mortality [39, 40].

In conclusion, obesity is independently associated with impaired quality of life in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Further studies are needed to determine if reducing obesity improves quality of life in patients with RA.

References

Manson JE, Bassuk SS (2003) Obesity in the United States: a fresh look at its high toll. JAMA 289(2):229–230

Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL (2004) Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA 291(10):1238–1245

Manson JE, Skerrett PJ, Greenland P, VanItallie TB (2004) The escalating pandemics of obesity and sedentary lifestyle. A call to action for clinicians. Arch Intern Med 164(3):249–258

Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Johnson CL (2002) Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2000. JAMA 288:1723–1727

Colditz GA, Willett WC, Rotnitzky A, Manson JE (1995) Weight gain as a risk factor for clinical diabetes mellitus in women. Ann Intern Med 122(7):481–486

Chan JM, Rimm EB, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC (1994) Obesity, fat distribution, and weight gain as risk factors for clinical diabetes in men. Diabetes Care 17(9):961–969

Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Giovannucci E et al (1995) Body size and fat distribution as predictors of coronary heart disease among middle-aged and older US men. Am J Epidemiol 141(12):1117–1127

Hubert HB, Feinleib M, McNamara PM, Castelli WP (1983) Obesity as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease: a 26-year follow-up of participants in the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 67(5):968–977

Kim KS, Owen WL, Williams D, Adams-Campbell LL (2000) A comparison between BMI and conicity index on predicting coronary heart disease: the Framingham Heart Study. Ann Epidemiol 10(7):424–431

Jia H, Lubetkin EI (2005) The impact of obesity on health-related quality-of-life in the general adult US population. J Public Health (Oxf) 27(2):156–164

Kortt MA, Clarke PM (2005) Estimating utility values for health states of overweight and obese individuals using the SF-36. Qual Life Res 14(10):2177–2185

Barajas Gutierrez MA, Robledo Martin E, Tomas Garcia N, Sanz Cueta T, Garcia Martin P, Cerrada Somolinos I (1998) Quality of life in relation to health and obesity in a primary care center. Rev Esp Salud Publica 72(3):221–231

Visser M, Bouter LM, McQuillan GM, Wener MH, Harris TB (1999) Elevated C-reactive protein levels in overweight and obese adults. JAMA 282(22):2131–2135

Khaodhiar L, Ling PR, Blackburn GL, Bistrian BR (2004) Serum levels of interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein correlate with body mass index across the broad range of obesity. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 28(6):410–415

Gabriel SE (2001) The epidemiology of rheumatoid arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 27(2):269–281

Pincus T, Callahan LF, Sale WG, Brooks AL, Payne LE, Vaughn WK (1984) Severe functional decline, work disability and increased mortality in seventy-five rheumatoid arthritis patients studied over nine years. Arthritis Rheum 27(8):864–872

Wolfe F, Mitchell DM, Sibley JT et al (1994) The mortality of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 37(4):481–494

Birrell FN, Hassell AB, Jones PW, Dawes PT (2000) How does the short form 36 health questionnaire (SF-36) in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) relate to RA outcome measures and SF-36 population values? A cross-sectional study. Clin Rheumatol 19(3):195–199

Dadoniene J, Uhlig T, Stropuviene S, Venalis A, Boonen A, Kvien TK (2003) Disease activity and health status in rheumatoid arthritis: a case-control comparison between Norway and Lithuania. Ann Rheum Dis 62(3):231–235

Abdel-Nasser AM, bd El-Azim S, Taal E, El-Badawy SA, Rasker JJ, Valkenburg HA (1998) Depression and depressive symptoms in rheumatoid arthritis patients: an analysis of their occurrence and determinants. Br J Rheumatol 37(4):391–397

Stavem K, Lossius MI, Kvien TK, Guldvog B (2000) The health-related quality of life of patients with epilepsy compared with angina pectoris, rheumatoid arthritis, asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Qual Life Res 9(7):865–871

West E, Jonsson SW (2005) Health-related quality of life in rheumatoid arthritis in Northern Sweden: a comparison between patients with early RA, patients with medium-term disease and controls, using SF-36. Clin Rheumatol 24(2):117–122

Talamo J, Frater A, Gallivan S, Young A (1997) Use of the short form 36 (SF36) for health status measurement in rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol 36(4):463–469

Cohen JD, Dougados M, Goupille P et al (2006) Health assessment questionnaire score is the best predictor of 5-year quality of life in early rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 33(10):1936–1941

Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA et al (1988) The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 31(3):315–324

Prevoo ML, van’t Hof MA, Kuper HH, van Leeuwen MA, van de Putte LB, van Riel PL (1995) Modified disease activity scores that include twenty-eight-joint counts. Development and validation in a prospective longitudinal study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 38(1):44–48

Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD (1992) The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 30(6):473–483

Dumville JC, Lee AJ, Smith FB, Fowkes FG (2004) The health-related quality of life of people with peripheral arterial disease in the community: the Edinburgh Artery Study. Br J Gen Pract 54(508):826–831

Carrasco GP, de Miguel DJ, Rejas GJ et al (2006) Negative impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on the health-related quality of life of patients. Results of the EPIDEPOC study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 4:31

Mena-Martin FJ, Martin-Escudero JC, Simal-Blanco F, Carretero-Ares JL, rzua-Mouronte D, Herreros-Fernandez V (2003) Health-related quality of life of subjects with known and unknown hypertension: results from the population-based Hortega study. J Hypertens 21(7):1283–1289

Jolly M (2005) How does quality of life of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus compare with that of other common chronic illnesses? J Rheumatol 32(9):1706–1708

Garratt A, Schmidt L, Mackintosh A, Fitzpatrick R (2002) Quality of life measurement: bibliographic study of patient assessed health outcome measures. BMJ 324(7351):1417

Ware JE Jr (2000) SF-36 health survey update. Spine 25(24):3130–3139

Pincus T, Sokka T, Kautiainen H (2005) Further development of a physical function scale on a MDHAQ [corrected] for standard care of patients with rheumatic diseases. J Rheumatol 32(8):1432–1439

Hassan MK, Joshi AV, Madhavan SS, Amonkar MM (2003) Obesity and health-related quality of life: a cross-sectional analysis of the US population. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 27(10):1227–1232

Engel SG, Crosby RD, Kolotkin RL et al (2003) Impact of weight loss and regain on quality of life: mirror image or differential effect? Obes Res 11(10):1207–1213

Esposito K, Pontillo A, Di Palo C et al (2003) Effect of weight loss and lifestyle changes on vascular inflammatory markers in obese women: a randomized trial. JAMA 289(14):1799–1804

Doll HA, Petersen SE, Stewart-Brown SL (2000) Obesity and physical and emotional well-being: associations between body mass index, chronic illness, and the physical and mental components of the SF-36 questionnaire. Obes Res 8(2):160–170

Escalante A, Haas RW, Del Rincon I (2005) Paradoxical effect of body mass index on survival in rheumatoid arthritis: role of comorbidity and systemic inflammation. Arch Intern Med 165(14):1624–1629

Kremers HM, Nicola PJ, Crowson CS, Ballman KV, Gabriel SE (2004) Prognostic importance of low body mass index in relation to cardiovascular mortality in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 50(11):3450–3457

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by a grant from the Hospital Nacional Edgardo Rebagliati Martins-EsSALUD, Lima, Peru. We are indebted to Dr. Ingrid Avalos for the critical review of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

García-Poma, A., Segami, M.I., Mora, C.S. et al. Obesity is independently associated with impaired quality of life in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol 26, 1831–1835 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-007-0583-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-007-0583-4