Abstract

To study the effect of thermal mineral water of Nagybaracska (Hungary) on patients with primary knee osteoarthritis in a randomized, double-blind clinical trial, 64 patients with nonsurgical knee joint osteoarthritis were randomly selected either into the thermal mineral water or into the tap water group in a non-spa resort village. The patients of both groups received 30-min sessions of bathing, 5 days a week for four consecutive weeks. The patients were evaluated by a blind observer immediately before and at the end of the trial using Western Ontario and McMaster Osteoarthritis (WOMAC) indices and follow-up assessment 3 months later. Twenty-seven patients of the 32 patients who received thermal mineral water and 25 of the 32 of those treated with tap water completed the trial. The WOMAC activity, pain, and total scores improved significantly in the thermal mineral-water-treated group. The improvement remained also at the end of the 3-month follow-up. The WOMAC activity, pain, and total scores improved significantly also in the tap water group at the end of the treatment course, but no improvement was detected at the end of the 3-month follow-up period. The treatment with the thermal mineral water of Nagybaracska significantly improved activity, pain, and total WOMAC scores of patients with nonsurgical OA of the knee. Even after 3 months, significant improvement was observed compared to the scores before the treatment or to tap water treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Thermal mineral water has been used to treat rheumatic complaints since prehistorical times [1]. Indeed, rheumatology practice and research began in European spas, such as Bath, England, Strathpeffer, Scotland and Aix-les-Bains, France. The spa-doctor, William Bruce (1835–1920), probably described polymyalgia rheumatica [2] while his fellow spa-doctor, Jacques Forestier (1890–1978) at Aix-les-Bains, France, introduced gold treatment for rheumatoid arthritis and described ankylosing hyperostosis of the spine [3]. It is perhaps useful to define the various terms employed in discussions of spa therapy. Spa is an acronym for salus per aquam (health through water). Most spas functions as holiday resorts, which clearly may affect the results of any studies. Bálint [4] has defined three areas for research: the first is hydrotherapy which is based on the physical characteristics of the water, the second is balneotherapy which is based on the chemical content of the minerals in the water, and the third is the whole ambience of spa treatment.

Although supporters of thermal mineral water treatment claim a special effect due to its solutes, there is little evidence that thermal mineral water treatments have different effects from hydrotherapy with heated tap water [5, 6]. Most of the trials were performed at spas, and the placebo effect of spa environments and concomitantly applied physiotherapy cannot be ruled out [7, 8]. Only a few randomized controlled trials have been performed with thermal mineral water in non-spa environments [9]. The purpose, therefore, of this study was to determine whether thermal mineral water is any better than heated tap water.

Methods and patients

The thermal mineral water of Nagybaracska—a small village in Southern Hungary—was used in this study. This was chosen as it is a non-spa resort, which might influence the results. The content of the mineral water is detailed on Table 1.

According to Hungarian legislation, the term “mineral water” can be used for natural spring waters or drilled wells, if the sum of cations and anions is more than 1,000 mg/litre, the water does not contain nitrite and/or nitrate anions, and the bacterial count does not exceed that of clear drinking water. For some ions, such as iodine or fluorine, the concentration of 1 mg/l is required for labeling the water as iodine or fluorine water. Analysis is performed and description of the water is issued by the Hungarian National Institute of Public Health [10]. By definition, thermal water has a temperature greater than 25°C in winter.

Patients between the age of 50 and 75 years with primary osteoarthritis of the knee (OA) according to the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria [11] were selected for the trial. All patients had bilateral “nonsurgical” knee joint OA. None of them had effusion or knee joint instability either before or after the treatment period and during the follow-up.

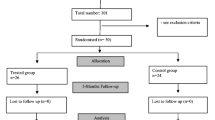

The patients lived locally within a radius of 20 km from Nagybaracska. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown on Table 2. Patients were randomly (using unrestricted randomization—simply tossing a coin to decide which of two treatments will be given to the next patient entering the trial) allocated either to treatment with mineral water or to the control group treated with heated tap water. The 32 patients in each group were comparable regarding age, gender, and disease parameters. All patients gave their written consent to participate in the study after full discussion of its nature. This was approved by the local and the regional Ethical Committee. Both the thermal mineral-water- and tap-water-treated patients were treated in individual tubs, with the temperature of bath waters at 34C°. This temperature is regarded also as “indifferent” similar to 36°C used in balneotherapy. We chose the lower temperature to avoid any inflammatory reaction, which might have been elicited by a higher temperature.

Because the heated tap water and the thermal mineral water did not differ in appearance or odor, making the tap water similar to the thermal water was not required, as had been necessary in previous studies [5]. Neither the assessing doctor (ÉS) nor the study doctor (AÁ) was aware of the type of treatment the patient received. This was only known to the study assistant, who provided thermal mineral water or tap water for the patients according to randomization. The patients had 30-min sessions, 5 days of the week for 4 weeks resulting in a 20-session treatment course.

The assessing physician (ÉS) was responsible for a detailed history and physical examination of each patient, confirming that the patient met the inclusion criteria and completed the Western Ontario and McMaster Osteoarthritis (WOMAC) score sheets. The same physician (ÉS) performed the initial evaluation, the evaluation at the end of the 4-week treatment and at the end of the 3-month follow-up assessment. The patients were allowed to take NSAID, analgesics in a standard dose during the trial and in the follow-up period. Extra analgesics were allowed during the trial but were recorded and reported by the patients. None of the patients took symptomatic slow-acting drugs in osteoarthritis (SYSADOA). Local injections or any other kind of treatment was not allowed during the trial and in the follow-up period, except regular exercises. The study doctor (AA) supervised the treatment sessions regularly measuring the pulse rate, blood pressure and also registered unconventional events and use of extra analgesics. Statistical analysis was performed by (IR) using paired t-tests and Wilcoxon tests.

Results

Five patients of the thermal mineral water group and seven patients of the tap water group did not finish the trial for reasons shown on Table 3. Twenty-seven patients (ten males and 17 females) of the thermal mineral water group and 25 patients (nine males and 16 females) of the tap water group finished the trial successfully, and their results have been evaluated and analyzed. The two groups remained comparable (data not shown).

The changes of outcome measures before and after the trial and at the end of the 3-month follow-up are shown on Tables 4 and 5. As shown in Table 5, the WOMAC activity, pain, and total scores significantly improved in the thermal mineral-water-treated group by the end of the treatment and remained so at the end of the three-month follow-up. The WOMAC activity, pain, and total scores also significantly improved in the tap water group at the end of the treatment course, but no significant improvement could be seen at the end of the 3-month follow-up period. There was no change in WOMAC stiffness scores in either group. No change of treatment was required during the trial in either group, and no extra analgesics were used. Two patients complained about increased pain in the thermal mineral water group after six to seven sessions, which lasted only for 2–3 days.

Two patients in the thermal mineral water group and one patient in the tap water group complained about itching after two to three treatment sessions, lasting only a few days. Three patients in the thermal mineral water group and two in the tap water group complained about increased diuresis. This latter complaint is a well-known consequence of head out immersion. One patient in the tap-water-treated group had mild diarrhea for 2 days, not requiring interruption of treatment.

Discussion

The treatment with the thermal mineral water of Nagybaracska significantly improved all the activity, pain, and total WOMAC scores of patients with nonsurgical OA of the knee. Even after 3 months, significant improvement could be registered compared to the scores before the start of the treatment. The stiffness score of WOMAC did not improve; it is well-known that this index is not very sensitive to change [12]. The WOMAC scores significantly improved in the tap-water-treated group at the end of the treatment. This finding is not unexpected as hydrotherapy, per se, is not placebo treatment and is an effective analgesic [13, 14]. No improvement of the tap-water-treated patients was observed after 3 months. Several studies have reported that thermal mineral water treatment is effective in reducing joint pain in osteoarthritis [5, 15–18]. In the first published controlled trial on the effect of balneotherapy, the pain was significantly decreased in the treatment group but the long-term effect was not studied [5]. Verhagen et al. [19] systematically reviewed numerous trials of balneotherapy and spa treatment in OA or rheumatoid arthritis and concluded that most trials reported positive findings (the absolute improvement in measured outcomes ranged from 0 to 44%), but most were methodologically flawed.

There is increasing number of reports on the use of balneotherapy in various rheumatic disorders. For example, Franke et al. [20] conducted a double-blind study and claimed the beneficial effect of the radon spa in rheumatoid arthritis. Sukenik et al. [21] have reported improvement (for a period of up to 3 months) in most of the clinical indices studied in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with sulfur baths and/or mud packs at the Dead Sea area. Beneficial effects of balneotherapy or spa treatment were also reported in patients with ankylosing spondylitis [22], fibromyalgia [23, 24], and psoriatic arthritis [25]. Furthermore, the cost effectiveness of combined spa–exercise therapy in ankylosing spondylitis was proven in a randomized controlled trial [26].

Our study has shown that thermal mineral water provides significant pain relief in nonsurgical osteoarthritis of the knee, and this was greater than that of tap water at the same temperature. This improvement persisted for 3 months after the trial was completed. The reason why thermal mineral water was superior has yet to be determined. Further studies comparing the results of thermal mineral water treatment and standard analgesics are now indicated.

In summary, we believe that there is sufficient evidence that natural thermal spa therapy can be used with good effect in patients with osteoarthritis [27, 28]. However, more research is required, especially large-scale trials, to properly establish not only the clinical benefits and limitations but also the cost–benefit of such treatment. It remains to be determined why thermal mineral water is better than ordinary tap water at the same temperature.

References

Jackson R (1990) Waters and spas in the classical world. Med Hist Suppl (10):1–13

Buchanan WW, Kean WF (2003) Dr. William Bruce (1835–1920), the Scottish highland spa at Strathpeffer; and a possible description of polymyalgia rheumatica. J R Coll Physicians Edinb 33(Suppl 12):29–35

Rakic M, Forestier J, July 27, 1890–March 15, 1978 (1978) Arthritis Rheum 21:989–990

Bálint GP How to research the effect of hydro- and balneotherapy and spa treatment? In T. Bender and H.G. Pratzel (eds) Health Resort Medicine in 2nd Millennium. Steffen, GmBH, Friedland MV-Germany ISMH Verlag 2004 p137

Szucs L, Ratkó I, Lesko T, Szoor I, Genti G, Bálint G (1989) Double-blind trial on the effectiveness of the Puspokladany thermal water on arthrosis of the knee-joints. J R Soc Health 109:7–9

Kovacs I, Bender T (2002) The therapeutic effects of Cserkeszölö thermal water in osteoarthritis of the knee: a double blind, controlled, follow-up study. Rheumatol Int 21:218–221

Bálint G, Bender T, Szabó E (1993) Spa treatment in arthritis. J Rheumatol 20:1623–1625

Guillemin F, Constant F, Collin JF, Boulange M (1994) Short and long-term effect of spa therapy in chronic low back pain. Br J Rheumatol 33:148–151

Konrad K, Tatrai T, Hunka A, Vereckei E, Korondi I (1992) Controlled trial of balneotherapy in treatment of low back pain. Ann Rheum Dis 51:820–822

Normative Decision of Health Ministry (1999/74) The Official Journal of Hungary

Altman, R, Asch E, Bloch D (1986) Development of criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis. Classification of osteoarthritis of the knee. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee of the American Rheumatism Association. Arthritis Rheum 29:1039–1049

Bellamy N, Goldsmith CH, Buchanan WW, Campbell J, Duku E (2002) Prior score availability: observations using the WOMAC osteoarthritis index. Br J Rheumatol 1991;30:150–151

Geytenbeek J (2002) Evidence for effective hydrotherapy. Physiotherapy 88:514–529

Bender T, Karagulle Z, Bálint GP, Gutenbrunner C, Bálint PV, Sukenik S (2005) Hydrotherapy, balneotherapy, and spa treatment in pain management. Rheumatol Int 25:220–224

Elkayam O, Wigler I, Tishler M et al (1991) Effect of spa therapy in Tiberias on patients with rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol 18:1799–1803

Yilmaz B, Goktepe AS, Alaca R, Mohur H, Kayar AH (2004) Comparison of a generic and a disease specific quality of life scale to assess a comprehensive spa therapy program for knee osteoarthritis. Joint Bone Spine 71:563–566

Guillemin F, Virion JM, Escudier P, De Talance N, Weryha G (2001) Effect on osteoarthritis of spa therapy at Bourbonne-les-Bains. Joint Bone Spine 68:499–503

Wigler I, Elkayam O, Paran D, Yaron M (1995) Spa therapy for gonarthrosis: a prospective study. Rheumatol Int 15:65–68

Verhagen AP, de Vet HC, de Bie RA, Kessels AG, Boers M, Knipschild PG (2000) Balneotherapy for rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2:CD000518

Franke A, Reiner L, Pratzel HG, Franke T, Resch KL (2000) Long-term efficacy of radon spa therapy in rheumatoid arthritis—a randomized, sham-controlled study and follow-up. Rheumatology 39:894–902

Sukenik S, Buskila D, Neumann L, Kleiner-Baumgarten A, Zimlichman S, Horowitz J (1990) Sulphur bath and mud pack treatment for rheumatoid arthritis at the Dead Sea area. Ann Rheum Dis 49:99–102

van Tubergen A, Landewe R, van der Heijde D et al (2001) Combined spa–exercise therapy is effective in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 45:430–438

Evcik D, Kýzýlay B, Gökçen E (2002) The effects of balneotherapy on fibromyalgia patients. Rheumatol Int 22:56–59

Neumann L, Sukenik S, Bolotin A et al (2004) The effect of balneotherapy at the Dead Sea on the quality of life of patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Clin Rheumatol 20:15–19

Sukenik S, Giryes H, Halevy S, Neumann L, Flusser D, Buskila D (1994) Treatment of psoriatic arthritis at the Dead Sea. J Rheumatol 21:1305–1309

Van Tubergen A, Boonen A, Landewe R et al (2002) Cost effectiveness of combined spa–exercise therapy in ankylosing spondylitis: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 47:459–467

van Tubergen A, van der Linden S (2002) A brief history of spa therapy. Ann Rheum Dis 61:273–275

Bender T, Bálint PV, Bálint GP (2002) A brief history of spa therapy. Ann Rheum Dis 61:949

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Pal Pacher for his technical help.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

W. Watson Buchanan: deceased

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bálint, G.P., Buchanan, W.W., Ádám, A. et al. The effect of the thermal mineral water of Nagybaracska on patients with knee joint osteoarthritis—a double blind study. Clin Rheumatol 26, 890–894 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-006-0420-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-006-0420-1