Abstract

Chronic musculoskeletal pain is a major—and growing—burden on today’s ageing populations. Professional organisations including the American College of Rheumatology (ACR), American Pain Society (APS) and European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) have published treatment guidelines within the past 5 years to assist clinicians achieve effective pain management. Safety is a core concern in all these guidelines, especially for chronic conditions such as osteoarthritis that require long-term treatment. Hence, there is a consensus among recommendations that paracetamol should be the first-line analgesic agent due to its favourable side effect and safety profile, despite being somewhat less effective in pain relief than anti-inflammatory drugs. Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2)-selective anti-inflammatory drugs were developed with the goal of delivering effective pain relief without the serious gastrointestinal (GI) side effects linked with traditional non-selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Clinical trial evidence supported these benefits, and COX-2 inhibitors were widely adopted, both in clinical practice and in official guidelines. Recently, accumulating data have linked COX-2 inhibitors with serious cardiovascular and/or cardiorenal effects and/or serious cutaneous adverse reactions (SCARs), particularly at anti-inflammatory doses or when used long term. Regulatory authorities in both Europe and the USA have responded to these data with the withdrawal of rofecoxib and valdecoxib, and the strengthening of prescribing advice on all anti-inflammatory drugs. COX-2 inhibitors and non-selective NSAIDs should now be used with increased caution in patients at increased cardiovascular and/or cardiorenal risk, e.g., patients with congestive heart failure, hypertension, etc. Regulatory advice and good clinical practice are to use anti-inflammatory drugs at the lowest effective dose and for the shortest possible time. There are as yet no updated official guidelines that incorporate these new data and regulatory advice. An international multidisciplinary panel, the Working Group on Pain Management, has generated new recommendations for the treatment of moderate-to-severe musculoskeletal pain. These guidelines, formulated in response to recent developments concerning COX-2 inhibitors and other NSAIDs, focus on paracetamol as the baseline drug for chronic pain management; when greater analgesia is desired, the addition of weak opioids is recommended based on a preferable GI and cardiovascular profile, compared with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Appropriate and up-to-date guidelines are crucial to optimise care for the large, and growing, population of patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Half of 3,605 respondents in a Scottish survey reported chronic pain, with back pain and arthritis the most common causes of pain (each 16% of total population) [1]. The prevalence of musculoskeletal pain increases with rising age [1, 2]. Chronic pain is twice as common in people aged more than 75 years compared with the 25- to 34-year age group [1]. Similarly, the rate of arthritis increases tenfold and musculoskeletal conditions overall increase fourfold between the 25- to 34-year and ≥75-year age ranges [2].

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have been widely used in the management of chronic musculoskeletal pain. The increased prevalence of chronic pain with increasing age is mirrored by a four- or fivefold higher rate of NSAID use in people aged 45 years and over, compared with the population below 45 years of age [3]. In a UK epidemiological study [3], almost one in five people between the ages of 65 and 74 years were taking NSAIDs. Non-specific NSAIDs such as ibuprofen offer effective pain relief in musculoskeletal conditions, at least in the short term, although evidence suggests that these agents have limited efficacy in complicated low back pain (for example, with sciatic pain) [4–7].

The analgesic efficacy of non-selective NSAIDs is offset by their associated risk of serious, and occasionally fatal, gastrointestinal (GI) complications [8, 9]. NSAID-associated GI complications are responsible for an estimated 16,500 deaths each year in patients with arthritis in the USA, according to data from the Arthritis, Rheumatism and Aging Medical Information System (ARAMIS) [8]. A meta-analysis of published randomised controlled trials linked NSAID use (for at least 2 months) with a 21% absolute risk of endoscopically diagnosed ulcer and 2.2% incidence of bleeding or perforation [9]. The same publication reported a relative risk of death of 3.4 for NSAID use, based on two randomised controlled trials and one cohort study including a total of 149,536 patients [9].

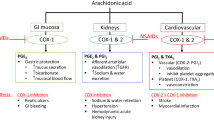

Traditional NSAIDs inhibit prostaglandin activity by blocking both cyclo-oxygenase (COX)-1 and COX-2 isozymes. COX-2-selective anti-inflammatory drugs were developed to offer an effective alternative to non-selective NSAIDs with a much-reduced risk of gastrointestinal side effects. Although this strategy initially appeared highly successful, there is growing evidence to link COX-2 inhibitors with cardiovascular complications.

This paper reviews the evolution of pain management guidelines in response to the availability of COX-2-selective anti-inflammatory drugs, before introducing updated guidance from the Working Group on Pain Management, which has been collated in response to recent developments concerning COX-2 inhibitors and other NSAIDs.

Current status of treatment guidelines

The first COX-2-selective anti-inflammatory drugs (celecoxib and rofecoxib) gained USA Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in December 1998 and May 1999, respectively. Randomised controlled trials had demonstrated that these agents offered similar analgesic efficacy to non-selective NSAIDs but with reduced GI side effects [10–13]. The availability of these new drugs prompted clinical organisations to issue new or updated guidelines that incorporated COX-2 inhibitors as an alternative to traditional NSAIDs.

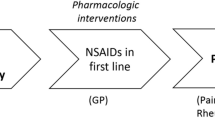

The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) published an update of their recommendations for the medical management of osteoarthritis of the hip and knee in 2000 [14]. These guidelines recommended paracetamol as the first-line pharmacological intervention (if non-pharmacological treatment proves inadequate), followed by either a COX-2-selective anti-inflammatory drug or an NSAID, which should be started at a low, analgesic dose and increased only if necessary to achieve effective pain relief [14]. Patients with risk factors for upper GI events should only receive non-selective NSAIDs in combination with a proton pump inhibitor or misoprostol [14]. It is worth noting that these risk factors include age 65 years or above, and the prevalence of musculoskeletal conditions such as an osteoarthritis increases with advancing age [2, 14]. The guidelines also suggested non-acetylated salicylates as an alternative option for high-risk patients, but highlighted the potential for ototoxicity and central nervous system toxicity when using these drugs [14]. Tramadol can be considered for use in patients who have contraindications to COX-2-specific inhibitors and non-selective NSAIDs, or in patients who have not responded to previous oral therapy. The ACR Guideline 2000 Update is summarised in Fig. 1.

A representation of the updated guideline for the management of osteoarthritis as established by American College of Rheumatology [14]. Abbreviations: COX-2, cyclo-oxygenase-2; PGE2, prostaglandin E2; PPI, proton pump inhibitor

In 2002, the American Pain Society (APS) also issued new guidelines for the management of pain in osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis and juvenile chronic arthritis [15]. These guidelines advised using paracetamol as the first-choice pharmacological agent for mild pain, and recommended COX-2-selective anti-inflammatory drugs for moderate-to-severe pain or inflammation in patients with no significant risk for hypertension or renal dysfunction. The APS considered that non-selective NSAIDs should be reserved for patients whose pain was insufficiently controlled by paracetamol (≤4 g/day) and/or COX-2 inhibitors, due to the risk of GI side effects [15].

Similarly, the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) released new recommendations for the treatment of knee osteoarthritis in 2003 [16]. These guidelines, based on an exhaustive evidence-based review of 545 publications, recommended paracetamol as the first-line oral analgesic agent because data showed that it was both effective (equivalent to ibuprofen in many patients) and had an acceptable safety profile in long-term use [16]. The review also concluded that topical administration of NSAIDs or capsaicin was effective and had a good safety record. Available data suggested that NSAIDs were generally more effective than paracetamol but carried an increased risk of GI side effects. Like the ACR and APS, EULAR recommended oral NSAIDs only for patients whose pain failed to respond to paracetamol, and stressed the need to opt for COX-2-selective drugs, or else to use gastroprotective agents with non-selective NSAIDs in patients at risk of GI events [16]. There were no robust data to show differences in efficacy between individual anti-inflammatory drugs [16]. Opioid analgesics, with or without paracetamol, are useful alternatives in patients in whom NSAIDs, including COX-2 selective inhibitors are contraindicated, ineffective or poorly tolerated. The 2003 EULAR recommendations are outlined in Table 1.

This rapid adoption of COX-2 inhibitors by clinical guidelines both in Europe and the USA reflects the high level of concern about GI events on non-selective NSAIDs. There was a clear consensus that these new agents offered an attractive alternative to traditional NSAIDs for at-risk patients who needed an additional, or alternative, analgesic to paracetamol.

Even at the time of development of these guidelines, new evidence was beginning to emerge that COX-2 inhibitors might carry their own safety risks. Data published since the current guidelines were released have led to new restrictions on the use of both COX-2 inhibitors and non-selective NSAIDs. These rapid developments have left guidelines as recent as 2003 out-of-step with current regulatory advice, and there is now a clear need for updated recommendations that reflect the current situation.

Anti-inflammatory drugs and cardiovascular events

The Vioxx Gastrointestinal Outcomes Research (VIGOR) trial was designed to compare GI side effects of the COX-2-selective drug rofecoxib with the non-selective NSAID naproxen in more than 8,000 patients with rheumatoid arthritis with a median follow-up of 9 months [17]. The results confirmed that rofecoxib carried a lower risk of GI events than naproxen (relative risk 0.5; p<0.001). However, the incidence of myocardial infarction (MI) was fourfold higher in rofecoxib-treated patients than in naproxen-treated patients (0.4 vs 0.1%; relative risk on naproxen 0.2; 95% confidence interval [95% CI]: 0.1–0.7) [17]. Cardiovascular mortality was the same (0.2%) in both treatment groups. Interestingly, the authors hypothesised that the difference in MI rates may have been due in part to a cardioprotective effect of naproxen rather than a deleterious effect of rofecoxib [17].

In 2004, a large-scale randomised controlled trial of rofecoxib as a prophylactic agent in patients with a history of colorectal adenoma, the Adenomatous Polyp Prevention on Vioxx (APPROVe) trial, revealed a doubling of cardiovascular risk in patients who received rofecoxib for more than 18 months (compared with placebo) [18]. Overall, the total relative risk for a confirmed thrombotic event on rofecoxib was 1.92 (95% CI: 1.19–3.11), which was statistically significant (p=0.008). In this analysis of thrombotic events, cardiac events were almost threefold more common (1.01 vs 0.36 patients/100 patient-years; hazard ratio 2.80 [95% CI: 1.19–3.11]) and cerebrovascular events more than twice as common (0.49 vs 0.21 patients/100 patient-years; hazard ratio 2.32 [(95% CI: 0.89–6.74]) [18]. Hypertension and oedema were reported more frequently in the rofecoxib compared with the placebo group (hazard ratios of 2.02 (95% CI: 1.71–2.38) and 1.57 (95% CI: 1.17–2.10), respectively) with the hazard ratio for the combined endpoint of congestive heart failure, pulmonary oedema or cardiac failure on rofecoxib of 4.61 (95% CI: 1.50–18.83) [18]. As a consequence of these findings, this trial was stopped early and rofecoxib was subsequently withdrawn from the market in 2004 [18, 19].

Results of the Adenoma Prevention with Celecoxib (APC) trial suggested that cardiovascular adverse events were due to a class effect of COX-2-selective anti-inflammatory drugs, not just rofecoxib [20]. In this trial, celecoxib was linked with a clear dose-dependent increase in both fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular events during this 3-year study in more than 2,000 patients. This increased risk was most marked for serious or fatal cardiovascular events: death from cardiovascular causes was threefold more common on celecoxib 400 mg/day (200 mg bid), and sixfold more common on celecoxib 800 mg/day (400 mg bid), compared with placebo [20]. For an aggregate endpoint of death from cardiovascular causes, non-fatal MI, stroke, heart failure, angina or need for a cardiovascular procedure, the hazard ratios were 1.5 (95% CI: 0.8–2.8) and 1.9 (95% CI: 1.0–3.3) for celecoxib 400 mg/day and 800 mg/day, respectively, vs placebo [20]. On the basis of these observations, the data safety monitoring board recommended early discontinuation of the study drug.

Evidence for a class effect also came from randomised controlled phase III trials of the COX-2-inhibitor valdecoxib and its intravenous prodrug parecoxib, in the management of post-operative pain [21, 22]. These studies demonstrated that in high-risk individuals (patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft [CABG] surgery), cardiovascular risk was increased with only 10–14 days of treatment with a COX-2 inhibitor [21, 22]. Although this increased cardiovascular risk failed to achieve statistical significance in the first trial, a large-scale safety study linked parecoxib and valdecoxib with an almost fourfold increase in cardiovascular events (risk ratio 3.7; p=0.03) compared with placebo after only 10 days of treatment [21, 22].

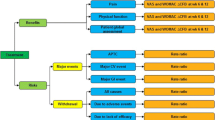

Recent publications now suggest that this class effect may extend to non-selective NSAIDs as well as COX-2-selective drugs [23, 24]. A nested case-control analysis that included 95,567 people in primary care found that patients who experienced a first MI (n=9,218) were significantly more likely than controls to have used rofecoxib, ibuprofen, diclofenac, naproxen or “other non-selective NSAIDs” within the previous 3 months (adjusted odds ratios 1.21–1.55; p values 0.005, <0.001, <0.001, 0.04, 0.03, respectively) [23]. Another nested case-control study, in a population of 908 heavy smokers with or without oral cancer, linked long-term NSAID use with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease-associated death (hazard ratio 2.06; p=0.001) (Fig. 2) [24].

Long-term use of NSAIDs may increase the risk of cardiovascular deaths [24]. Abbreviations: CV, cardiovascular; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug

The response from regulatory authorities

The FDA issued interim recommendations in December 2004, advising clinicians to assess individual GI and cardiovascular risk before prescribing a COX-2-selective or non-selective anti-inflammatory drug [25]. Patients were reminded that they should consult a physician before using an over-the-counter (OTC) NSAID for more than 10 days.

Both American (FDA) and European (European Medicines Agency; EMEA) regulatory authorities met to discuss safety concerns with anti-inflammatory drugs during February 2005, after which they concluded that there was a class effect of COX-2-selective anti-inflammatory drugs on cardiovascular risk [26, 27]. The FDA advised that non-selective NSAIDs should be considered separately, but that they carried a suspected cardiovascular risk in long-term use in the absence of clear evidence for their safety. All prescription NSAIDs were required to carry a boxed warning, and OTC NSAID labelling changed to include specific warnings about potential serious GI or cardiovascular risks, with increased emphasis on the need to limit dose and duration of non-prescription use [28]. The EMEA advised that all COX-2 inhibitors were contraindicated in patients with ischaemic heart disease or stroke and also in patients with peripheral arterial disease, and should be used with caution in patients with cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension or diabetes [29]. Prescribers were advised to use the lowest effective dose for the shortest possible time [29]. Valdecoxib was withdrawn due to cardiovascular concerns and serious skin reactions at the request of the FDA and after discussions with the EMEA [28, 30].

The EMEA confirmed its advice on COX-2 inhibitors in June 2005 and released recommendations on non-selective NSAIDs in August 2005 (confirmed in October 2005) based on a safety review by its Committee on Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) [29, 31, 32]. Prescribers were advised to consider overall safety profiles of non-selective NSAIDs in the context of individual patient risk factors, and that “all patients should take the lowest effective dose of non-selective NSAIDs for the shortest time necessary to control symptoms”.

Hence, current regulatory advice states that COX-2-selective anti-inflammatory drugs are contraindicated for many patients at increased cardiovascular risk, while both COX-2-selective and non-selective NSAIDs should be used with caution in patients with a history of hypertension and/or heart failure. Both COX-2-selective and non-selective NSAIDs should be used at the lowest effective dose and for the shortest possible time. These restrictions mean that prescribers must find alternatives for many patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain (many of whom are elderly and hence at elevated cardiovascular and/or GI risk), but at the time of writing no official updated guidelines were available.

Development of updated guidelines

The Working Group on Pain Management (WGPM; http://www.painworkinggroup.org) was formed in response to the need for updated advice on the management of chronic musculoskeletal pain. The group has reviewed recent developments at two meetings in December 2004 and June 2005. The WGPM developed its recommendations using evidence-based medicine, expert opinion and clinical vignettes at the second meeting, which was held during the annual EULAR congress in Vienna.

These recommendations were developed through a discussion of three clinical vignettes, i.e., hypothetical cases designed to simulate actual cases. These vignettes were carefully prepared to ensure that they adequately covered important diagnostic categories for pain management and forced ranking of treatment options. Expert validation was provided by Sunil Panchal, Chair of the NCCN Guidelines for Cancer Pain Management and a member of the AAPM Board of Directors; Joseph Pergolizzi, a member of both the Coalition for Pain Education and the International Pain Research and Treatment Foundation Boards of Directors; and Alex Macario, Director of Health Outcomes Research at Stanford University School of Medicine.

The vignettes focused on the management of moderate-to-severe pain in three major indications: osteoarthritis, back pain, and sports injury and/or joint surgery pain. For each indication, the group was presented with a range of potential clinical scenarios in turn to ensure that their recommendations were as comprehensive as possible.

Moderate-to-severe osteoarthritis pain

In general, non-pharmacological therapy should be given whenever possible. Recommendations include controlled weight loss, physiotherapy and application of ice or heat to the affected area. Nutritional supplements such as glucosamine and chondroitin sulphate may also be of value [33, 34].

If arthrosis is confined to a single joint then the first-line pharmacological intervention should be an intra-articular steroid injection. In the long term, severe cases should be considered for joint replacement.

Arthrosis that affects multiple joints should be considered an indication for systemic analgesia, as outlined in Fig. 3. For patients without cardiovascular, renal or GI risk factors, the choice of analgesic drug is dictated by both the severity and likely duration of the pain (Fig. 3a). An arthritis flare requires effective short-term management. Moderate flare pain may respond well to either a short course of NSAID or a weak opioid combination such as paracetamol plus tramadol, while severe pain may demand treatment using strong opioid drugs. Paracetamol plus tramadol is also appropriate for the management of long-term pain that may be due to worsening underlying disease. It is also relevant to note that a patient who presents with moderate-to-severe osteoarthritis pain is likely to be already receiving paracetamol for chronic mild-to-moderate pain. Fixed-dose combination therapy using paracetamol plus tramadol builds on this long-term maintenance therapy without increasing the pill burden for the patient. Opioids and NSAIDs are recommended as an adjuvant treatment to paracetamol. However, as there is a possibility that the maximum total daily dose can be exceeded on adding a combination regimen to a single-agent regimen, it may be better to switch treatment from single-agent paracetamol to the paracetamol plus tramadol regimen.

Many patients with osteoarthritis are at increased GI risk due to factors such as advanced age [35]. These patients may benefit from a short course of COX-2-selective anti-inflammatory drugs, or non-selective NSAIDs in combination with a proton pump inhibitor to treat an acute flare, while the paracetamol plus tramadol combination offers a well-tolerated alternative for long-term pain management. COX-2 inhibitors should be avoided in patients who are at increased cardiovascular or renal risk, and, with continuing uncertainty about cardiovascular effects of non-selective NSAIDs, it seems advisable to apply similar caution to all anti-inflammatory drugs. Current regulatory advice is that NSAIDs should be used with caution in patients with cardiovascular and renal diseases and with cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension. Weak opioid combinations, particularly paracetamol plus tramadol, are recommended for these patients. Appropriate oral analgesic agents for at-risk individuals are summarised in Fig. 3b.

Moderate-to-severe lower back pain

Effective management of lower back pain (LBP) should include both pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions. Indeed, analgesic drug therapy should be generally regarded as a means to help the patient to regain function by reducing pain during physical therapy. Psychosocial assessment may also be valuable in the long term, and behavioural therapy or other interventions for depression may be required.

Facet joint injection is indicated for some patients, but most will require systemic analgesia (Fig. 4). Drug selection should reflect the aetiology of LBP, which often represents a combination of nociceptive and neuropathic pain. Tramadol is particularly appropriate in this context because it has demonstrated efficacy against both types of pain [4]. The multimodal combination of paracetamol plus tramadol is an effective and well-tolerated choice for most patients with moderate-to-severe LBP, including elderly patients who are often renally impaired and/or at increased cardiovascular risk [36]. Young, healthy individuals could receive anti-inflammatory drugs, either alone or at a reduced dose, in combination with paracetamol plus tramadol. There was a strong consensus, however, that paracetamol plus tramadol should be the preferred choice for long-term pain management.

Pain from injury and/or joint surgery

The WGPM reviewed pain after acute injury (such as a sports injury) in three phases: (1) acute sports injury; (2) post-operative pain after day-care surgery and (3) rehabilitation. There was consistent agreement on the value of a multimodal approach to pain management throughout all three phases.

(1) Acute sports injury

Anti-inflammatory doses of NSAIDs are recommended for the initial treatment for a moderately painful sports injury in a young patient. If these drugs prove inadequate and/or pain worsens, then paracetamol, weak opioid combinations, tramadol and strong opioids may be added as required (Fig. 5a). However, NSAIDs should not be started in patients who are referred for immediate surgery due to the associated risk of bleeding, and should be stopped at least five half-lives before a planned surgical procedure.

Therapeutic options for treating moderate-to-severe pain following injury: (a) immediately following injury, (b) after day-care surgery, and (c) supporting rehabilitation. Abbreviations: COX-2, cyclo-oxygenase-2; IR, immediate release; SR, sustained release; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; PRN, use on an as needed basis

(2) Post-operative pain after day-care surgery

Systemic analgesia should be stepped down from day 3 after surgery, as shown in Fig. 5b. COX-2 inhibitor or non-selective NSAID therapy should be given for no more than 3–5 days. Opioid agents should be stepped down as the need for pain control diminishes until the patient is receiving baseline therapy with paracetamol alone.

(3) Rehabilitation

Stepping down treatment after surgery should mean that patients are receiving baseline paracetamol for chronic pain management, but additional analgesia may be required to enable patients to follow their rehabilitation programme (Fig. 5c). Short-term use of non-selective NSAIDs or COX-2 inhibitors can be beneficial in controlling inflammatory pain and supporting active rehabilitation, but this should be limited in duration. In addition, opioid agents and weak opioid combinations can alleviate both baseline pain and pain during motion.

Conclusions

Recent developments, including newly published data and regulatory reviews and advice, have brought dramatic changes to the range of analgesic drugs that are advisable—or even available—to use in the management of moderate-to-severe musculoskeletal pain.

Both USA and European regulatory authorities have advised restricting the use of COX-2 inhibitors (and, to a lesser extent, non-selective NSAIDs), and treatment guidelines must now evolve to reflect these outcomes.

The target population for pain management is expanding due to ageing populations, and these patients are likely to have an increased GI and/or cardiovascular risk. There is a growing need for effective and safe analgesic agents that are appropriate for this vulnerable population.

This need has prompted an increasing appreciation of the value of multimodal analgesia in the management of moderate-to-severe pain, and the combination paracetamol plus tramadol has emerged as a particularly useful candidate for chronic pain management.

References

Elliott AM, Smith BH, Penny KI, Smith WC, Chambers WA (1999) The epidemiology of chronic pain in the community. Lancet 354:1248–1252

March LM, Bagga H (2004) Epidemiology of osteoarthritis in Australia. Med J Aust 180(5 Suppl):S6–S10

Blower AL, Brooks A, Fenn GC et al (1997) Emergency admissions for upper gastrointestinal disease and their relation to NSAID use. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 11:283–291

Boureau F, Legallicier P, Kabir-Ahmadi M (2003) Tramadol in post-herpetic neuralgia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Pain 104:323–331

van Tulder MW, Scholten RJ, Koes BW, Deyo RA (2000) Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for low back pain: a systematic review within the framework of the Cochrane Collaboration Back Review Group. Spine 25:2501–2513

van Tulder MW, Scholten RJ, Koes BW, Deyo RA (2000) Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2):CD000396

Koes BW, Scholten RJ, Mens JM, Bouter LM (1997) Efficacy of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for low back pain: a systematic review of randomised clinical trials. Ann Rheum Dis 56:214–223

Singh G, Triadafilopoulos G (1999) Epidemiology of NSAID induced gastrointestinal complications. J Rheumatol 26(Suppl 56):18–24

Tramer MR, Moore RA, Reynolds DJ, McQuay HJ (2000) Quantitative estimation of rare adverse events which follow a biological progression: a new model applied to chronic NSAID use. Pain 85:169–182

Emery P, Zeidler H, Kvien TK et al (1999) Celecoxib versus diclofenac in long-term management of rheumatoid arthritis: randomised double-blind comparison. Lancet 354:2106–2111

Malmstrom K, Daniels S, Kotey P, Seidenberg BC, Desjardins PJ (1999) Comparison of rofecoxib and celecoxib, two cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors, in postoperative dental pain: a randomized, placebo- and active-comparator-controlled clinical trial. Clin Ther 21:1653–1663

Laine L, Harper S, Simon T et al (1999) A randomized trial comparing the effect of rofecoxib, a cyclooxygenase 2-specific inhibitor, with that of ibuprofen on the gastroduodenal mucosa of patients with osteoarthritis. Rofecoxib Osteoarthritis Endoscopy Study Group. Gastroenterology 117:776–783

Schnitzer TJ, Truitt K, Fleischmann R et al (1999) The safety profile, tolerability, and effective dose range of rofecoxib in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Phase II Rofecoxib Rheumatoid Arthritis Study Group. Clin Ther 21:1688–1702

American College of Rheumatology Subcommittee on Osteoarthritis Guidelines (2000) Recommendations for the medical management of osteoarthritis of the hip and knee: 2000 update. Arthritis Rheum 43:1905–1915

Simon LS, Lipman AG, Jacox AK et al (2002) Pain in osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis and juvenile chronic arthritis. In: Clinic practice guideline, no. 2. American Pain Society (APS), Glenview, IL, pp 179

Jordan KM, Arden NK, Doherty M et al (2003) EULAR recommendations 2003: an evidence-based approach to the management of knee osteoarthritis [Report of a task force of the Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutic Trials (ESCISIT)]. Ann Rheum Dis 62:1145–1155

Bombardier C, Laine L, Reicin A, VIGOR Study Group (2000) Comparison of upper gastrointestinal toxicity of rofecoxib and naproxen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 343:1520–1528

Bresalier RS, Sandler RS, Quan H et al (2005) Cardiovascular events associated with rofecoxib in a colorectal adenoma chemoprevention trial. N Engl J Med 352:1092–1102

Merck press release. Merck announces voluntary worldwide withdrawal of Vioxx. http://www.vioxx.com/rofecoxib/vioxx/consumer/press_release_09302004.jsp. Accessed November 2005

Solomon SD, McMurray JJ, Pfeffer MA, Adenoma Prevention with Celecoxib (APC) Study Investigators et al (2005) Cardiovascular risk associated with celecoxib in a clinical trial for colorectal adenoma prevention. N Engl J Med 352:1071–1080

Ott E, Nussmeier NA, Duke PC, Multicenter Study of Perioperative Ischemia (McSPI) Research Group, Ischemia Research and Education Foundation (IREF) Investigators et al (2003) Efficacy and safety of the cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitors parecoxib and valdecoxib in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 125:1481–1492

Nussmeier NA, Whelton AA, Brown MT et al (2005) Complications of the COX-2 inhibitors parecoxib and valdecoxib after cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med 352:1081–1091

Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C (2005) Risk of myocardial infarction in patients taking cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors or conventional non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: population based nested case-control analysis. BMJ 330:1366

Sudbo J, Lee JJ, Lippman SM et al (2005) Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and the risk of oral cancer: a nested case-control study. Lancet 366(9494):1359–1366

FDA talk paper. FDA issues public health advisory recommending limited use of COX-2 inhibitors. December 2004. Downloaded November 2005. http://www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/ANSWERS/2004/ANS01336.html

EMEA press statement, 17 February 2005 European Medicines Agency announces regulatory action on COX-2 inhibitors. http://www.emea.eu.int/pdfs/human/press/pr/6275705en.pdf. Accessed November 2005

FDA memorandum, April 6, 2005. Downloaded November 2005. http://www.fda.gov/cder/drug/infopage/COX2/NSAIDdecisionMemo.pdf

FDA public health advisory. FDA announces important changes and additional warnings for COX-2 selective and non-selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). April 7, 2005. Downloaded November 2005.http://www.fda.gov/cder/drug/advisory/COX2.htm

EMEA press release, 27 June 2005. European Medicines Agency concludes action on COX-2 inhibitors. http://www.emea.eu.int/pdfs/human/press/pr/20776605en.pdf. Accessed November 2005

EMEA press statement, 7 April 2005. European Medicines Agency statement on the suspension of use of Bextra. http://www.emea.eu.int/htms/hotpress/h12163705.htm. Accessed November 2005

EMEA press release, 2 August 2005. Accessed November 2005

EMEA press release, 17 October 2005. European Medicines Agency update on non-selective NSAIDs. http://www.emea.eu.int/pdfs/human/press/pr/29896405en.pdf. Accessed November 2005

Towheed TE, Maxwell L, Anastassiades TP et al (2005) Glucosamine therapy for treating osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2):CD002946

Uebelhart D, Malaise M, Marcolongo R et al (2004) Intermittent treatment of knee osteoarthritis with oral chondroitin sulfate: a one-year, randomized, double-blind, multicenter study versus placebo. Osteoarthr Cartil 12:269–276

Moore N, Charlesworth A, Van Ganse E et al (2003) Risk factors for adverse events in analgesic drug users: results from the PAIN study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 12:601–610

Selvin E, Erlinger TP (2004) Prevalence of and risk factors for peripheral arterial disease in the United States. Results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999-2000. Circulation 110:738–743

Disclosures/financial interests

Professor Schnitzer has acted in the capacity of consultant for GlaxoSmithKline, Grünenthal, Merck & Co., Inc, Nicox and Novartis. He has received clinical research support from Endo Pharmaceuticals, Merck & Co., Inc., Novartis, Pfizer and Winston. He has no equity interest to declare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Financial interests/disclosures: Professor Schnitzer has acted in the capacity of consultant for GlaxoSmithKline, Grünenthal, Merck & Co., Inc, Nicox and Novartis. He has received clinical research support from Endo Pharmaceuticals, Merck & Co., Inc., Novartis, Pfizer and Winston, and is a member of the Speakers’ Bureau for Merck & Co., Inc., Ortho-McNeil and Pfizer. He has no equity interest to declare.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schnitzer, T.J. Update on guidelines for the treatment of chronic musculoskeletal pain. Clin Rheumatol 25 (Suppl 1), 22–29 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-006-0203-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-006-0203-8