Abstract

Background

Chronic pain after inguinal hernioplasty is the foremost side-effect up to 10–30% of patients. Mesh fixation may influence on the incidence of chronic pain after open anterior mesh repairs.

Methods

Some 625 patients who underwent open anterior mesh repairs were randomized to receive one of the three meshes and fixations: cyanoacrylate glue with low-weight polypropylene mesh (n = 216), non-absorbable sutures with partially absorbable mesh (n = 207) or self-gripping polyesther mesh (n = 202). Factors related to chronic pain (visual analogue scores; VAS ≥ 30, range 0–100) at 1 year postoperatively were analyzed using logistic regression method. A second analysis using telephone interview and patient records was performed 2 years after the index surgery.

Results

At index operation, all patient characteristics were similar in the three study groups. After 1 year, chronic inguinal pain was found in 52 patients and after 2 years in only 16 patients with no difference between the study groups. During 2 years’ follow-up, three (0.48%) patients with recurrences and five (0.8%) patients with chronic pain were re-operated. Multivariate regression analysis indicated that only new recurrent hernias and high pain scores at day 7 were predictive factors for longstanding groin pain (p = 0.001). Type of mesh or fixation, gender, pre-operative VAS, age, body mass index or duration of operation did not predict chronic pain.

Conclusion

Only the presence of recurrent hernia and early severe pain after index operation seemed to predict longstanding inguinal pain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

After the spread of mesh techniques in inguinal hernia repair, the research focus has shifted from recurrences to chronic pain in both open and laparoscopic techniques. Chronic inguinal pain may occur after 10–30% of procedures when mesh is used [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. Identification and preservation of inguinal nerves during surgery may decrease the frequency of chronic pain. Pain reaction is, however, related to various patient-dependent and surgical factors. Chronic pain may relate to irritation or damage of inguinal nerves [10], mesh fixation [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21] or weight of the used mesh [2,3,4]. High pre-operative pain scores, lower age, female gender, recurrent hernia surgery, repair of bilateral hernia, and post-operative complications have all been identified as risk factors for longstanding groin pain after surgery [22, 23]. Original fixation of the mesh in Lichtenstein hernioplasty was performed by using non-absorbable sutures medially at the pubic periost and continuous sutures at the inguinal ligament [24]. Since that, various mesh fixation methods have been advocated such as absorbable sutures [11, 12, 25], various tissue glues [9, 13,14,15,16,17, 21, 25] and self-fixating meshes [18,19,20, 25]. Our recent study shows that fixation of mesh by tissue glue or using a self-gripping mesh did not cause less chronic pain than fixation by conventional sutures [25]. In the present study, this prospectively collected data [25] was re-analyzed using the multivariate binomial regression model to find variables that were independently associated with the presence of chronic pain after 1 year of operation. We also evaluated these patients 2 years after index operation to analyze the temporal course of pain.

Methods

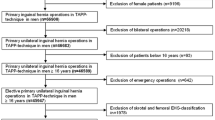

This randomized prospective trial was conducted in eight Finnish hospitals between January 2012 and December 2013 [25]. The study participants (n = 650) were over 18-year-old male or female patients with uni- or bilateral hernias. The patients with previous recurrent hernias were also accepted into the study. Patients were enrolled consecutively from the waiting list and randomly allocated to receive one of the following treatment options: non-absorbable mesh (Optilene mesh 60 g/m2, B. Braun, Melsungen, Germany, n = 216) fixed with tissue glue (Histoacryl, B. Braun, Melsungen, Germany), partly absorbable mesh (Ultrapro 7.6 × 15 cm, 28 g/m2, Ethicon, Somerville, NJ, n = 207) fixed with non-absorbable sutures (2-0 Prolene, Ethicon, Somerville, NJ) or self-gripping mesh (Parietex Progrip, Covidien, Minneapolis, MN). The mesh was individually trimmed and placed between the inguinal ligament, the pubic bone and internal oblique aponeurosis. Indirect hernia sacs were either resected or inverted into the abdominal cavity. In case of a large direct hernia sac, the sac was inverted to abdominal cavity by 3-0 absorbable sutures. In the glue group mesh was fixed by gluing the mesh to inguinal ligament, over pubic bone and transversalis fascia. Mesh slit cross-over was also glued. In the suture group mesh was fixed to inguinal ligament using continuous non-absorbable suture, over pubic bone with one suture and over the transversalis fascia with one suture. The mesh slit cross-over was fixed with a single suture. The exclusion criteria were large scrotal hernia, known femoral hernia, strangulated hernia or patient refusal. All the operations were performed by senior consultant surgeons (n = 10) having wide experience in inguinal hernia surgery. More detailed description of methodology and interventions have been published previously [25]. Patients complaining chronic inguinal pain at 1 year were re-analyzed using multivariate regression analysis to identify predictive factors for chronic inguinal pain, and then analyzed again 2 years after the surgery.

Two years after surgery we conducted a standardized telephone interview and a review of computerized patient records for the patients who were complaining chronic pain at 1 year. Pain was analyzed by study nurses or first author who did not know patients study group. VAS score ≥ 30 at either rest or exercise was defined as chronic pain.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was made using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 22.0 for Windows (IBM SPSS Statistic 22.0, USA). For categorical variables we used Pearson’s χ2-test or Fisher’s exact test, and for numerical variables independent samples t test or Mann–Whitney U test. Predictor variables were entered simultaneously in a multivariate binomial regression model to find those that were independently associated with presence of chronic pain at 1 year. Missing data were considered random. The regression models omitted any incomplete sets of variable measurement. An α value of 0.05 was chosen to mark statistical significance.

Results

Baseline demographic data are presented in Table 1. There were no significant differences in patient characteristics (demographic data) between the randomized groups, except that the mean operating time was shorter in the glue and self-gripping group than in the suture group. Follow-up rate was 94% at 1 year; 198 patients in the glue group, 192 in the self-gripping mesh group, and 195 in the suture group were reached for follow-up. Primary operation due to recurrent hernia was slightly more common in the glue group although the difference was not statistically significant. Some 20–30% of hernias in each group were medium to large in size and the rest were considered small (size of defect less than 1.5 cm). The patients who reported VAS score ≥ 30 at 1 year were followed up for 2 years. None of these patients were lost to follow-up. Results were equal between the studied groups (Table 2). After 1 year, 52 (8%) of the patients reported chronic pain. One year later only 16 of these 52 patients reported chronic pain and a total of 8 patients were re-operated; 3 for new recurrence and 5 for chronic pain. For patients complaining chronic pain a mesh removal was performed. Some six patients needed analgesics for their inguinal pain at 2 years postoperatively. Results of logistic regression analysis for independent predictors of chronic pain are presented in Table 3. Appearance of a new symptomatic recurrent hernia and immediate postoperative high pain scores (VAS at day 7) were the only predictive factors for chronic inguinal pain after open anterior mesh repair.

Discussion

The rate of chronic pain 1 year after open anterior mesh repair varies from 10 to 30% [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. In the present study [25] the rate (VAS ≥ 30) at 1 year was as low as 8.7%. This relatively low amount of pain can be explained by the fact that senior surgeons were performing the surgery. Since chronic pain is probably the most demanding challenge of modern inguinal hernia surgery we wanted to follow-up those patients reporting chronic pain at 1 year after surgery. This subgroup showed significant reduction in pain between 1 and 2 years (52 versus 16 patients). Similar findings of decreased pain over time have been reported previously [26,27,28,29,30,30]. There were no significant differences between the study groups in long-term pain reaction, need of re-operations, need of analgesics or in recurrence rate. At 1 year none of the patients had been re-operated due to chronic pain, but at 2 years 5 patients (0.8% of the entire patient population) complaining chronic pain without recurrence had their mesh removed. Removal of the mesh did not cause a recurrent hernia due to the strong scar tissue induced by the mesh. This indicates that the timing of reoperation is important, because chronic pain tends to resolve even after 1 year of index operation. Our study suggests that “wait and see” conservative policy is recommended in chronic pain even up to 2 years after the index operation.

In a recent similar study, Pierides et al. found by using multivariate binomial regression model that complications, hernia recurrence, mesh weight, pre-operative VAS score and age were predictors for chronic pain after open inguinal hernia mesh repair [23]. Hallén et al. did a multivariate analysis on Swedish hernia register to find predictors for reoperation due to chronic pain after herniorrhaphy [22]. They reported female sex, lower age, bilateral repair, operation on recurrence and direct hernia as predictive factors. Our RCT study did not confirm these results since in our study new symptomatic recurrent hernias and severe early postoperative pain response were the only predictive factors for chronic inguinal pain. We have not assessed the symptomless recurrences in the whole patient cohort (n = 625) using ultrasound or clinical study. Therefore, we do not have data of exact recurrence numbers (and their relation to chronic pain) in the present study. One reason for this discrepancy may be that the Swedish study included different types of hernia repairs including endoscopic ones. Also many studies use register data [1, 22, 23, 31], whereas our study is a randomized controlled trial. A great advantage of our study is that it was a prospective carefully planned and controlled trial with multiple hospitals and surgeons involved. Data collection was highly reliable and drop-outs were minimal.

Whether mesh attachment or mesh physical characteristics have influence on chronic pain has been discussed since the introduction of mesh repairs for inguinal hernia [2,3,4, 11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. Results of these various trials have been rather incoherent and it has been unsure whether these have a true effect on post herniorrhaphy inguinodynia. Today a large amount of studies are available and some conclusions can be drawn. Three good-quality meta-analyses show that self-gripping meshes have similar results with the traditional penetrating suture fixation techniques in open anterior hernia repair [32,33,34,35]. Also a good-quality meta-analysis indicates that light weight mesh causes less foreign body sensation when compared to heavy-weight mesh [36]. Triple neurectomy has been used to treat difficult chronic inguinal pain after open anterior mesh repair [37]. A recent meta-analysis indicates that routine neurectomy can prevent post-operative pain, but the effect is only short-term [38]. Cochrane database systematic review indicates that glue fixation of the mesh may reduce post-operative pain but again the effect is only short term [39].

It seems that chronic pain after open anterior inguinal hernia repair is a complex entity with multiple factors of origin. According to our study it seems that meticulous dissection and gentle surgical technique remain as the only way to prevent or decrease chronic postoperative pain after tension-free inguinal hernia repair. Our study also indicated that if the patient has severe pain days after inguinal hernia surgery, surgeon should consider immediate re-operation to look for possible nerve entrapment. Non-operative option would be to give effective pain medication to avoid chronic pain syndrome. A remarkable finding of our study is that the patients having high pain scores at 7 days after surgery did not have high preoperative pain scores. This is somewhat in contrast between previous studies showing correlation between high preoperative pain scores and postoperative pain.

Change history

06 June 2018

In the original publication, co-authors affiliations were incorrect.

References

Bay-Nielsen M, Perkins FM, Kehlet H, Danish Hernia Database (2001) Pain and functional impairment 1 year after inguinal herniorrhaphy: a nationwide questionnaire study. Ann Surg 233:1–7

O’Dwyer PJ, Kingsnorth AN, Molloy RG et al (2005) Randomized clinical trial assessing impact of a lightweight or heavyweight mesh on chronic pain after inguinal hernia repair. Br J Surg 92:166–170

Bringman S, Wollert S, Osterberg J et al (2006) Three-year results of a randomized clinical trial of lightweight or standard polypropylene mesh in Lichtenstein repair of primary inguinal hernia. Br J Surg 93:1056–1059

Post S, Weiss B, Willer M, Neufang T, Lorenz D (2004) Randomized clinical trial of lightweight composite mesh for Lichtenstein inguinal hernia repair. Br J Surg 91:44–48

Callesen T, Bech K, Kehlet H (1999) Prospective study of chronic pain after groin hernia repair. Br J Surg 86:1528–1531

Poobalan AS, Bruce J, King PM et al (2001) Chronic pain and quality of life following open inguinal hernia repair. Br J Surg 88:1122–1126

Paajanen H, Scheinin T, Vironen J. Commentary (2010) Nationwide analysis of complications related to inguinal hernia surgery in Finland: a 5 year register study of 55 000 operations. Am J Surg 199:746–751

Jeroukhimov I, Wiser I, Karasic E et al (2014) Reduced postoperative chronic pain after tension-free inguinal hernia repair using absorbable sutures: a single-blind randomized clinical trial. J Am Coll Surg 218:102–107

Negro P, Basile F, Brescia A et al (2011) Open tension-free Lichtenstein repair of inguinal hernia: use of fibrin glue versus sutures for mesh fixation. Hernia 15:7–14

Heise CP, Starling JR (1998) Mesh inguinodynia: a new clinical syndrome after inguinal herniorrhaphy? J Am Coll Surg 187:514–518

Paajanen H (2002) Do absorbable mesh sutures cause less chronic pain than nonabsorbable sutures after Lichtenstein inguinal herniorrhaphy? Hernia 6:26–28

Jeroukhimov I, Wiser I, Karasic E, Nesterenko V, Poluksht N, Lavy R, Halevy A (2014) Reduced postoperative chronic pain after tension-free inguinal hernia repair using absorbable sutures: a single-blind randomized clinical trial. J Am Coll Surg 218(1):102–107

Canonico S, Santoriello A, Campitiello F, Fattopace A, Corte AD, Sordelli I et al (2005) Mesh fixation with human fibrin glue (Tissucol) in open tension-free inguinal hernia repair: a preliminary report. Hernia 9:330–333

Campanelli G, Champault G, Pascual MH, Hoeferlin A, Kingsnorth A, Rosenberg J et al (2008) Randomized, controlled, blinded trial of Tissucol/Tisseel for mesh fixation in patients undergoing Lichtenstein technique for primary inguinal hernia repair: rationale and study design of the TIMELI trial. Hernia 12:159–165

Nowobilski W, Dobosz M, Wojciechowicz T, Mionskowska L (2004) Lichtenstein inguinal hernioplasty using butyl-2-cyanoacrylate versus sutures. Preliminary experience of a prospective randomized trial. Eur Surg Res 36:367–370

Negro P, Basile F, Brescia A et al (2011) Open tension-free Lichtenstein repair of inguinal hernia: use of fibrin glue versus sutures for mesh fixation. Hernia 15(1):7–14

Moreno-Egea A (2014) Is it possible to eliminate sutures in open (Lichtenstein technique) and laparoscopic (totally extraperitoneal endoscopic) inguinal hernia repair? A randomized controlled trial with tissue adhesive (n-hexyl-α-cyanoacrylate). Surg Innov 21(6):590–599

Chatzimavroudis G, Papaziogas B, Koutelidakis I et al (2014) Lichtenstein technique for inguinal hernia repair using polypropylene mesh fixed with sutures vs.self-fixating polypropylene mesh: a prospective randomized comparative study. Hernia 18(2):193–198

Kapischke M, Schulze H, Caliebe A (2010) Self-fixating mesh for the Lichtenstein procedure—a prestudy. Langenbecks Arch Surg 395:317–322

Bruna Esteban M, Cantos Pallarés M, Artigues Sánchez de Rojas E, Vila MJ (2014) Prospective randomized trial of long-term results of inguinal hernia repair using autoadhesive mesh compared to classic Lichtenstein technique with sutures and polypropylene mesh. Circ Esp 92(3):195–200

Paajanen H, Kössi J, Silvasti S, Hulmi T, Hakala T (2011 Sep) Randomized clinical trial of tissue glue versus absorbable sutures for mesh fixation in local anaesthetic Lichtenstein hernia repair. Br J Surg 98:1245–1251

Hallén M, Sevonius D, Westerdahl J, Gunnarsson U, Sandblom G (2015) Risk factors for reoperation due to chronic groin postherniorrhaphy pain. Hernia 19:863–869

Pierides GA, Paajanen HE, Vironen JH (2016) Factors predicting chronic pain after open mesh based inguinal hernia repair: a prospective cohort study. Int J Surg 29:165–170

Lichtenstein IL, Shulman AG, Amid PK, Montllor MM (1989) The tension-free hernioplasty. Am J Surg 157:188–193

Rönkä K, Vironen J, Kössi J, Hulmi T, Silvasti S, Hakala T, Ilves I, Song I, Hertsi M, Juvonen P, Paajanen H (2015) Randomized multicenter trial comparing glue fixation, self-gripping mesh, and suture fixation of mesh in lichtenstein hernia repair (FinnMesh Study). Ann Surg 262(5):714–719 (discussion 719–20).

Kim-Fuchs C, Angst E, Vorburger S, Helbling C, Candinas D, Schlumpf R (2012) Prospective randomized trial comparing sutured with sutureless mesh fixation for Lichtenstein hernia repair: long-term results. Hernia 16(1):21–27

Droeser RA, Dell-Kuster S, Kurmann A et al (2014) Long-term follow-up of a randomized controlled trial of Lichtenstein’s operation versus mesh plug for inguinal hernia. Ann Surg 359:966–972

Paajanen H, Rönkä K, Laurema A (2013) A single-surgeon randomized trial comparing three meshes in lichtenstein hernia repair: 2- and 5-year outcome of recurrences and chronic pain. Int J Surg 11:81–84

Suwa K, Nakajima S, Hanyu K (2013) el al. Modified Kugel herniorraphy using strandardized dissection technique of the preperitoneal space: long-term operative outcome in consecutive 340 patients with inguinal hernia. Hernia 17:699–707

Pierides G, Vironen J (2011 Aug) A prospective randomized clinical trial comparing the Prolene Hernia System® and the Lichtenstein patch technique for inguinal hernia repair in long term: 2- and 5-year results. Am J Surg 202(2):188–193

Huerta S, Patel PM, Mokdad AA, Chang J (2016) Predictors of inguinodynia, recurrence, and metachronous hernias after inguinal herniorrhaphy in veteran patients. Am J Surg 212(3):391–398

Ismail A, Abushouk AI, Elmaraezy A, Abdelkarim AH, Shehata M, Abozaid M, Ahmed H, Negida A (2017 Jul) Self-gripping versus sutured mesh fixation methods for open inguinal hernia repair: a systematic review of clinical trials and observational studies. Surgery 162(1):18–36

Fang Z, Zhou J, Ren F, Liu D (2014) Self-gripping mesh versus sutured mesh in open inguinal hernia repair: system review and meta-analysis. Am J Surg 207(5):773–781

Li J, Ji Z, Li Y (2014) The comparison of self-gripping mesh and sutured mesh in open inguinal hernia repair: the results of meta-analysis. Ann Surg 259(6):1080–1085

Molegraaf M, Kaufmann R, Lange J (2017) Comparison of self-gripping mesh and sutured mesh in open inguinal hernia repair: a meta-analysis of long-term results. Surgery 163(2):351–360

Śmietański M, Śmietańska IA, Modrzejewski A, Simons MP, Aufenacker TJ (2012) Systematic review and meta-analysis on heavy and lightweight polypropylene mesh in Lichtenstein inguinal hernioplasty. Hernia 16(5):519–528

Moore AM, Bjurstrom MF, Hiatt JR, Amid PK, Chen DC (2016) Efficacy of retroperitoneal triple neurectomy for refractory neuropathic inguinodynia. Am J Surg 212(6):1126–1132

Barazanchi AW, Fagan PV, Smith BB, Hill AG (2016) Routine neurectomy of inguinal nerves during open onlay mesh hernia repair: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Ann Surg 264(1):64–72

Sun P, Cheng X, Deng S, Hu Q, Sun Y, Zheng Q (2017) Mesh fixation with glue versus suture for chronic pain and recurrence in Lichtenstein inguinal hernioplasty. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MM: Data gathering, analysis, writing of the paper. EA: Data gathering. JK: Clinical work (operations), data gathering, pre-review of the paper. II: clinical work, data gathering. TH: clinical work. SS: Clinical work. MH: clinical work, data gathering. KM: clinical work, data gathering. HP: clinical work, data gathering, pre-review of the paper, writing of the paper. JV: clinical work, data gathering, pre-review of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was accepted by ethical commitee of Kuopio University Hospital.

Human and animal rights

This study compared three well accepted and routinely used techniques to treat inguinal hernias. No human or animal rights were violated.

Informed consent

Informed consent has been collected from all the patients accepted in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Matikainen, M., Aro, E., Vironen, J. et al. Factors predicting chronic pain after open inguinal hernia repair: a regression analysis of randomized trial comparing three different meshes with three fixation methods (FinnMesh Study). Hernia 22, 813–818 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-018-1772-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-018-1772-6