Abstract

Purpose

Recurrence rates after femoral hernia repair (FHR) have not been reliably established in the USA. We sought to determine this trend over time.

Methods

The proportion of primary and recurrent FHRs was determined for patients age ≥ 18 from: ACS-NSQIP (1/2005–12/2014), Premier (1/2010–09/2015), and institutional (1/2005–12/2014) data. Trends were analyzed using a one-tailed Cochran–Armitage test.

Results

In the NSQIP database, 6649 patients underwent a FHR. In females, the proportion of FHRs performed for recurrence decreased from 14.0% in 2005 to 6.2% in 2014, p = 0.02. In males, there was no change: 16.7–16.1% 2005–2014 (p = 0.18). The Premier database included 4495 FHRs and our institution 315 FHRs. There was no difference for either gender over time in either data source, all p > 0.05.

Conclusions

The proportion of femoral hernia repairs performed for recurrence in the USA remained relatively constant in males in two large national databases between 2005 and 2015. In females, a decrease was seen in one of the large national databases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In comparison with inguinal hernias, femoral hernias are uncommon, accounting for 2–4% of groin hernia repairs [1,2,3,4]. Approximately 30,000 femoral hernia repairs (FHR) are performed annually in the United States [5]. In contrast to inguinal hernias, femoral hernias are more likely to require emergent repairs and are associated with a higher complication rate and morbidity [6,7,8]. Therefore, although rare, identifying the risk and risk factors of recurrence following FHR in this patient population is of great importance.

Currently, there is a paucity of consistent data regarding the recurrence rate following groin hernia repairs, especially FHRs in the United States [9]. Around the world, the recurrence rate after FHR ranges from 0 to 6.1% for primary repairs and increases after previous repair [2,3,4, 7, 10,11,12,13,14,15]. In Sweden, this reported rate has been decreasing since 1984 and was approximately 2–3% in 1994 [4]. In the United States, while reported recurrence rates vary between 0 and 3%, [16, 17] the majority of these studies are outdated or are composed of small sample sizes with limited follow-up and do not adequately assess the state of FHR across the USA as a whole. To assess the current state of FHRs throughout the USA, we evaluated the proportion of FHRs performed for recurrence and the associated trends over time using national databases and data from our multi-site academic medical center.

Materials and methods [9]

Following Institutional Review Board approval, all patients age ≥ 18 years who underwent FHR were identified from three sources: American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) database, the Premier database, and institutional data. The NSQIP database was composed of between 121 and 517 hospitals during the study period of January 1, 2005–December 31, 2014. The Premier database was composed of data from over 600 US hospitals during the study period of January 1, 2010–September 30, 2015. Our institutional data included three Mayo Clinic academic sites (Rochester, MN; Scottsdale, AZ; Jacksonville, FL) and were evaluated between January 1, 2005 and December 31, 2014. Patients were identified using International Classification of Disease-9th Revision (ICD-9) post-operative diagnoses (ICD-9 551.0X, 552.0X, 553.0X) and surgical procedure codes (ICD-9 53.21, 53.29, 53.31, 53.39) or Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes (CPT 49,550, 49553, 49555, 49557). Post-operative diagnoses were selected, as they are available in the large national databases. For inclusion, NSQIP and institutional patients were required to have a CPT for FHR or primary (NSQIP) or any (institutional) post-operative ICD-9 diagnosis code for FHR with concomitant CPT procedure code 49659. Premier patients were required to have a primary post-operative ICD-9 diagnosis of FHR and either (1) CPT for FHR or (2) DRG 350–352 and ICD-9 procedure for FHR.

Comorbidities including diabetes (ICD-9: 250.XX) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD; ICD-9: 496) were identified by ICD-9 diagnosis codes in Premier and institutional databases; in the NSQIP database these comorbidities were identified using database-specific variables DIABETES and HXCOPD. Obesity was defined as body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30 in our NSQIP and institutional data. In the Premier data, obesity was identified by ICD-9 diagnosis codes (278.0, 278.00, 278.01). Cases were classified as an emergent repair based on the presence of NSQIP-defined emergent status (NSQIP only), ASA class 5 (NSQIP only), ventilator dependence, preoperative SIRS, sepsis, or septic shock, current pneumonia, wound infection, acute renal failure, any perioperative blood transfusion of at least 1 unit red blood cells, coma, disseminated cancer, or ICD-9 diagnosis code for gangrenous (551.0X) or obstructed (552.0X) hernia. Pregnant patients (identified by ICD-9 codes: 640–649, 650–659, V22, V23 or V28) and those undergoing robotic repair (ICD-9 codes: 17.4x, CPT: S2900) were excluded from the study.

The incidence of primary (CPT 49550 49553) and recurrent (CPT 49555 49557) FHRs was evaluated in all data sources, stratified by sex. If a FHR CPT code did not indicate primary or recurrent hernia repair (CPT 49659), ICD-9 diagnoses were used to indicate primary (551.00, 551.02, 552.00, 552.02, 553.00, 553.02) or recurrent (551.01, 551.03, 552.01, 552.03, 553.01, 553.03) repair. To be coded as s recurrent FHR, the prior repair should be a FHR on the ipsilateral side. ICD-9 diagnoses were also used to indicate bilateral (551.02, 551.03, 552.02, 552.03, 553.02, 553.03) or unilateral (551.00, 551.01, 552.00, 552.01, 553.00, 553.01) FHR.

Patient demographics, comorbidities, and surgical factors were compared using χ2 and Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate. Trends over time were evaluated for a decrease using a one-tailed Cochran–Armitage test. Statistically significant and clinically relevant variables from the univariate analysis were analyzed by multivariable logistic regression for association with recurrent versus initial FHR. For analyses where sex was found to be statistically significant over time on univariate analysis, we tested for an interaction between sex and year of operation to determine if sex stratification on multivariable analysis was necessary. Outcomes of the multivariable models were reported as odds ratio (OR) with associated 95% confidence interval (CI). Obesity and smoking status were not able to be obtained for institutional data and were, therefore, not adjusted for on logistic regression analysis. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. For unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression analyses, missing data were handled with indicator variables (bilateral repair; NSQIP [n = 2164], obesity; NSQIP [N = 356]). Missing data were not included for univariate proportional analyses. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS Version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary NC). These methods have been previously described in a prior study focused on recurrence rates following inguinal hernia repair [9].

The American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program and the hospitals participating in the ACS NSQIP are the source of the data used herein; they have not verified and are not responsible for the statistical validity of the data analysis or the conclusions derived by the authors.

Results

NSQIP database

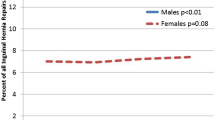

In the NSQIP database, 6649 FHR patients (72.6% female) underwent FHR. Patient characteristics are reported in Table 1. In females, the proportion of FHRs performed for recurrence decreased over the study period from 14.0% in 2005 to 6.2% in 2014 (p = 0.02). In males, there was no change over time: the proportion performed for recurrence was 16.7% in 2005 and 16.1% in 2014 (p = 0.18, Fig. 1).

On univariate analysis, evaluation of year of operation, age, bilateral versus unilateral repair (or unknown), COPD, smoking status, and inpatient versus outpatient admission were not statistically significant for an association with performance of FHR performed for recurrence. Females (OR 0.66, 95% CI 0.56–0.79), emergent repair (OR 0.82, 95% CI 0.70–0.97), and diabetics (OR 0.48, 95% CI 0.28–0.81) had a decreased likelihood of repair for recurrence. Obesity was the only variable that reached statistical significance for an increased risk of patients needing to undergo FHR for recurrence (OR 1.32, 95% CI 1.01–1.72), Table 2.

Females were found to have a significant decrease in FHR over the study period on univariate analysis; therefore, our multivariable analysis was tested for an interaction between years (as a continuous variable) and sex. Due to the finding of a statistically significant interaction (p = 0.04), we stratified our NSQIP data by sex. When stratified by sex, in females, year of operation (OR 0.96, 95% CI 0.919–0.998) and emergent operation (OR 0.71, 95% CI 0.55–0.92) were associated with a decrease of the proportion of recurrent FHRs, while obesity (OR 1.48, 95% CI 1.07–2.03) and inpatient admission (OR 1.42, 95% CI 1.09–1.86) were associated with an increased likelihood. In males, diabetics were associated with a decreased likelihood of having a repair for recurrence (OR 0.16, 95% CI 0.05–0.52) while inpatient admission (OR 1.42, 95% CI 1.01–1.99) was associated with an increased likelihood. Year of operation, age, emergent repair, unilateral versus bilateral repair, obesity, COPD, and smoking status did not reach statistical significance (all p > 0.05), Table 2.

Premier database

The Premier database contained data on 4495 (76.2% female) FHRs. The majority of patients undergoing FHR were ≥ 65 (60.5%) years of age, Table 3. In contrast to the NSQIP database, there was no significant difference over time for the proportion of FHR performed for recurrence in either sex. In females, 8.3% of repairs were performed for recurrence in 2010 and 4.7% in 2015 (p = 0.10). In males, the rate was 22.6% in 2010 and 21.1% in 2015 (p = 0.08), Fig. 2.

On univariate analysis, evaluation of year of diagnosis, age, bilateral repair, teaching institution, urban versus rural hospital location, geographic location within the United States, and hospital bed size were not statistically significant for an increased or decreased likelihood of undergoing a FHR for recurrence. Females (OR 0.38, 95% CI 0.30–0.46), patients undergoing emergent repair (OR 0.36, 95% CI 0.29–0.44), and diabetics (OR 0.60, 95% CI 0.37–0.98) had a decreased likelihood of undergoing repair for recurrence (Table 4).

Multivariable analysis showed that year of diagnosis, inpatient (versus outpatient) admission, bilateral repair, obesity, COPD, and smoking status did not increase or decrease the risk of undergoing a FHR for recurrence. Female sex (OR 0.38, 95% CI 0.31–0.47), those undergoing emergent repair (OR 0.45, 95% CI 0.32–0.62), and diabetics (OR 0.62, 95% CI 0.38–1.00) again had a decreased likelihood of undergoing repair for recurrence. Patients over age 74 (versus 18–24) were more likely to undergo a repair for recurrence (OR 1.41, 95% CI 0.47–4.19); this was the only age group to reach statistical significance (Table 4).

Institutional data

Within our institution, 315 patients (66.7% female) underwent FHR during the study period, Table 1. There was no difference for the proportion of FHRs performed over time for recurrence in either sex (females 0% in 2005 and 2014, p = 0.14; males 0% in 2005 to 15.4% (n = 2) in 2014, p = 0.15); however, we were underpowered as only 17 recurrent repairs occurred for females (and 12 for males) during the study period (Fig. 3).

On univariate analysis, emergent repair was the only variable to reach statistical significance, and was associated with a decreased likelihood of repair for recurrence (OR 0.38, 95% CI 0.15–0.97), Table 5. No variables reached statistical significance on multivariable analysis; Table 5.

Discussion

Through evaluation of two national databases, we showed that the proportion of FHRs performed for recurrence has been decreasing in females in the NSQIP database, while it has remained constant in the Premier database. In males, the proportion has remained constant in both databases. This proportion of recurrent FHRs is likely between 5 and 6% in females and between 16 and 21% in males in the United States. Unfortunately, our institutional analysis, despite combining data from three high volume institutions, was underpowered and, therefore, we were unable to draw conclusions from this analysis. This highlights the rarity of the procedure, which limits research on this topic.

Our reported proportion of FHRs for recurrence is much higher than the prior reports of recurrence rates ranging from 0 to 6.1% following FHR [2,3,4, 7, 10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. This is especially interesting, as using reoperation for recurrence as a surrogate marker for hernia recurrence has been shown to underestimate the true recurrence rate by over 40% [18]. One reason for the difference in our findings is the use of our large study population compared to numerous single institution studies with smaller numbers of femoral hernia patients. Studies from single institutions vary greatly, as the inter-hospital variation has been shown to be between 3 and 20% [18]. This finding signifies that recurrence following FHR continues to be a clinical concern in the United States.

We included both primary recurrent FHRs and those who underwent multiple repairs for recurrences in our evaluation. A previous study at a large volume hernia center estimated the recurrence rate following primary hernia repair to be 6.1%, which increased to an average of 22.2% for multiple recurrences [15]. Furthermore, they showed that 55% of recurrences occurred within 1-year of operation and 67% within 1-years of operation [15]. The majority of previous studies have a follow-up of less than 2-years, likely missing up to one-third of recurrences [3, 12,13,14, 19]. Taking these factors into account, and combining our female and male patients into one cohort, our findings are likely similar to prior comparable reports from other countries [15].

In all of our data sources, greater than two-thirds of our patients were female. Females composed the majority of patients in both the primary and recurrent repair cohorts. It is well known that femoral hernias are more common in females [8, 10, 11, 15, 19,20,21,22]. Our analysis of the NSQIP database showed a decrease in the proportion of repairs performed for recurrence in females throughout the study period. Possible reasons for this decrease include an increased identification of femoral hernias in females, either from evaluation by laparoscopic surgical techniques, physical exam, or imaging evaluation, resulting in an increased number of primary repairs that occurred throughout the study period, offsetting the ratio of recurrent to primary repairs. Another possible explanation could be a decreased rate of recurrent repairs due to improved laparoscopic techniques, as surgeons have continued to perfect their laparoscopic techniques for FHRs over the study period. Finally, there may be a less complex patient cohort in the NSQIP dataset over time as more regional hospitals joined than larger national academic centers over the study period.

We also found that more patients presented in need of an emergent repair for primary repairs, but had planned procedures for recurrent hernias. This was further shown in our multivariable analysis, where women and those undergoing emergent repair were at decreased risk of having a repair performed for recurrence in both of our national databases. While it is known that patients with femoral hernias are more likely to present in an emergent situation, our study showed that this risk may decrease after a previous repair [6,7,8, 10, 11, 23]. Additionally, we showed that diabetics have a decreased likelihood of undergoing a repair for recurrence. Diabetes, COPD, obesity, and smoking are all medical comorbidities that can be associated with a decreased life expectancy that could shorten the duration for a recurrence to occur. The other explanation could be that these patients are less likely to have a recurrence surgically repaired due to their medical comorbidities, if symptoms are mild.

By evaluating two large national databases, we were able to estimate the recurrence rate after a FHR in the United States, using the proportion of procedures performed for recurrence as a surrogate for the true rate. The differences between our findings in the NSQIP and Premier data sources likely stem from the variation in the composition of each database. NSQIP is composed of quality-seeking hospitals, which are largely composed of academic medical centers. Premier Incorporated is a purchasing group, with a subset of participating hospitals contributing to their medical database, providing a more heterogeneous composition of hospitals than the NSQIP database. Currently, the United States does not have a national groin hernia database to follow patients longitudinally to determine the true recurrence rate following FHR [9]. We, therefore, evaluated the proportion of FHRs for recurrence in multiple different data sources, as this provides a more representative depiction of the current state of femoral hernia repairs across the United States than just one data source.

In addition to acknowledging that reoperation is an underestimate of the true recurrence rate, our study has other limitations. Using national databases, we cannot follow individual patients over time and a single patient can be captured in the database many times, if he or she undergoes subsequent FHRs for recurrence. Therefore, our reported rates are higher than what they would be for primary recurrent repairs alone. Additionally, it is likely that a subset of patients were in both the NSQIP and our institutional data, and in NSQIP and the Premier databases. Finally, hospitals in NSQIP are focused on quality improvement, while Premier is a purchasing group; therefore, these two groups may not be perfectly representative of the overall state of recurrent hernia repairs across the entire United States [9].

Conclusions

National databases show the proportion of femoral hernia repairs performed for recurrence remained relatively constant in males in the United States between 2005 and 2015. In females, a decrease was seen in one of the national databases. This proportion was between 5 and 6% in females and 16–21% in males in the United States. As the proportion of repairs performed for recurrence underestimates the true recurrence rate, the recurrence rate following femoral hernia repairs in the USA are likely much higher than previously reported and continue to be an important clinical outcome.

References

Bay-Nielsen M, Kehlet H, Strand L, Malmstrom J, Andersen FH, Wara P et al (2001) Quality assessment of 26,304 herniorrhaphies in Denmark: a prospective nationwide study. Lancet (London England) 358:1124–1128

Glassow F (1985) Femoral hernia. Review of 2105 repairs in a 17 year period. Am J Surg 150:353–356

Hernandez-Richter T, Schardey HM, Rau HG, Schildberg FW, Meyer G (2000) The femoral hernia: an ideal approach for the transabdominal preperitoneal technique (TAPP). Surg Endosc 14:736–740

Sandblom G, Gruber G, Kald A, Nilsson E (2000) Audit and recurrence rates after hernia surgery. Eur J Surg Acta Chirurgica 166:154–158

Rutkow IM (2003) Demographic and socioeconomic aspects of hernia repair in the United States in 2003. Surg Clin North Am 83:1045–1051 (v–vi)

Beadles CA, Meagher AD, Charles AG (2015) Trends in emergent hernia repair in the United States. JAMA Surg 150:194–200

Dahlstrand U, Wollert S, Nordin P, Sandblom G, Gunnarsson U (2009) Emergency femoral hernia repair: a study based on a national register. Ann Surg 249:672–676

Humes DJ, Radcliffe RS, Camm C, West J (2013) Population-based study of presentation and adverse outcomes after femoral hernia surgery. Br J Surg 100:1827–1832

Murphy BL, Ubl DS, Zhang J, Habermann EB, Farley DR, Paley K (2017) Trends of inguinal hernia repairs performed for recurrence in the United States. Surgery 163(2):343–350

Andresen K, Bisgaard T, Kehlet H, Wara P, Rosenberg J (2014) Reoperation rates for laparoscopic vs open repair of femoral hernias in Denmark: a nationwide analysis. JAMA Surgery 149:853–857

Alimoglu O, Kaya B, Okan I, Dasiran F, Guzey D, Bas G et al (2006) Femoral hernia: a review of 83 cases. Hernia J Hernias Abdom Wall Surg 10:70–73

Pangeni A, Shakya VC, Shrestha AR, Pandit R, Byanjankar B, Rai S (2017) Femoral hernia: reappraisal of low repair with the conical mesh plug. Hernia J Hernias Abdom Wall Surg 21:73–77

Cox TC, Huntington CR, Blair LJ, Prasad T, Heniford BT, Augenstein VA (2016) Quality of life and outcomes for femoral hernia repair: does laparoscopy have an advantage. Hernia J Hernias Abdom Wall Surg 21:79–88

Cox TC, Huntington CR, Blair LJ, Prasad T, Heniford BT, Augenstein VA (2017) Quality of life and outcomes for femoral hernia repair: does laparoscopy have an advantage? Hernia J Hernias Abdom Wall Surg 21:79–88

Bendavid R (1989) Femoral hernias: primary versus recurrence. Int Surg 74:99–100

Thill RH, Hopkins WM (1994) The use of Mersilene mesh in adult inguinal and femoral hernia repairs: a comparison with classic techniques. Am Surg 60:553–556 (discussion 6–7)

Waltz P, Luciano J, Peitzman A, Zuckerbraun BS (2016) Femoral hernias in patients undergoing total extraperitoneal laparoscopic hernia repair: including routine evaluation of the femoral canal in approaches to inguinal hernia repair. JAMA Surg 151:292–293

Kald A, Nilsson E, Anderberg B, Bragmark M, Engstrom P, Gunnarsson U et al (1998) Reoperation as surrogate endpoint in hernia surgery. A three year follow-up of 1565 herniorrhaphies. Eur J Surg Acta Chirurgica 164:45–50

Song Y, Lu A, Ma D, Wang Y, Wu X, Lei W (2015) Long-term results of femoral hernia repair with ULTRAPRO plug. J Surg Res 194:383–387

Henriksen NA, Thorup J, Jorgensen LN (2012) Unsuspected femoral hernia in patients with a preoperative diagnosis of recurrent inguinal hernia. Hernia J Hernias Abdom Wall Surg 16:381–385

Rosemar A, Angeras U, Rosengren A, Nordin P (2010) Effect of body mass index on groin hernia surgery. Ann Surg 252:397–401

Sucandy I, Kolff JW (2012) Incarcerated femoral hernia in men: incidence, diagnosis, and surgical management. North Am J Med Sci 4:617–618

Malek S, Torella F, Edwards PR (2004) Emergency repair of groin herniae: outcome and implications for elective surgery waiting times. Int J Clin Pract 58:207–209

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank the Mayo Clinic Department of Surgery, the Kern Center for the Science of Health Care Delivery, and Medtronic as substantial contributors of resources to this project.

Funding

The Mayo Clinic Robert D. and Patricia E. Kern Center for the Science of Health Care Delivery provides salary support for Dr. Habermann, Dr. Murphy, and Mr. Ubl. Dr. Jianying Zhang is an employee of Medtronic and provided the analysis of the Premier Database. No external funding was used. This work was presented as an e-poster presentation at the Southwest Surgical Congress Annual Meeting in Maui, Hawaii April 2017.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

BM declares no conflict of interest DU declares no conflict of interest. JZ declares no conflict of interest. EH declares no conflict of interest. DF declares no conflict of interest. KP declares no conflict of interest.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. Zhang is an employee of Medtronic and completed the analysis of the Premier database. We teamed with Medtronic to help perform the statistical analyses of the Premier database due to their expertise in analyzing this extensive data source. Medtronic shared in our goals of identifying the current state of hernia repairs in the United States as a whole and offered to partner with us for this study. Dr. Zhang performed the statistical analysis of the Premier data, which was critically evaluated and discussed among all authors. All authors were involved in data interpretation. Our agreement with Medtronic precluded financial considerations for this project.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Human and animal rights

This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

For this type of study formal consent is not required.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Murphy, B.L., Ubl, D.S., Zhang, J. et al. Proportion of femoral hernia repairs performed for recurrence in the United States. Hernia 22, 593–602 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-018-1743-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-018-1743-y