Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to compare postoperative pain between the open tension-free plug and patch (PP) technique and the totally extraperitoneal patch (TEP) hernioplasty.

Methods

One hundred and fifty-four male patients with unilateral inguinal hernia were randomized to undergo PP and TEP from 2005 to 2009. Pain assessment was conducted using the numerical rating scale (NRS) and the McGill Pain Questionnaire preoperatively, 6, 12 and 24 months postoperatively. All patients received the same analgesic regimen and documented pain in a NRS-based 4-week diary.

Results

Of the 154 patients 77 underwent TEP and 77 PP. Median follow-up was 3.8 years. One recurrent hernia was observed in the TEP and two in the PP group (p = 0.56). Median preoperative NRS scores were 2 and 2, 0.3 and 0.4 at 6 months, 0.1 and 0.3 at 12 months, 0.2 and 0.1 at 24 months postoperatively in the PP and TEP groups, respectively (p > 0.05). Data from the 4-week pain diaries revealed significant differences in pain intensity between the two different techniques from the second postoperative week (p < 0.05). Patients in the PP group required more additional analgesics on day four and five postoperatively (p = 0.037 and 0.015, respectively).

Conclusions

Our data favor the TEP technique concerning postoperative pain as primary endpoint between tension-free PP and TEP hernia repair.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Groin hernia repair is one of the most common surgical procedures performed in standard surgery units worldwide. No unique consensus exists for the best method for treating primary unilateral groin hernia and the use of light-weighted meshes is widely debated [1]. Chronic postoperative pain after mesh repair is a significant parameter of quality-of-life and a recognized long-term complication of inguinal hernia repair [2]. About 10 % of the patients suffer from chronic pain following mesh-based groin hernia repair, however, chronic pain was significantly less when the repair was performed laparoscopically [3]. This study was designed to compare two tension-free techniques of groin hernia repair: laparoscopic totally extraperitoneal hernioplasty (TEP) [4] and plug and patch (PP) open repair (Rutkow technique) [5]. The primary aim of this study was to analyze the postoperative pain and analgesic consumption. The secondary end point was to evaluate differences in recurrence rate and complications.

Materials and methods

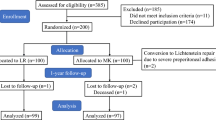

The study was designed as a prospective randomized-controlled trial and was conducted in a single surgical unit at a tertiary-care referral hospital. One hundred and fifty-four patients were randomized to undergo TEP or PP under general anesthesia from March 2005 to September 2009. All recruited patients were randomly allocated, by means of sealed envelopes, to one of the two study arms. The sample size of n = 80 per group was prespecified to detect a difference of 10 mm in the NRS assuming a standard deviation of 17.5 mm with a statistical power of 90 %. All consecutive male patients aged 18 years or older with a primary and unilateral, symptomatic groin hernia Nyhus grade I–III [6] were included in the trial. Exclusion criteria are shown in Table 1. The comparative data for the two study groups are demonstrated in Table 2. Informed consent was obtained from all patients. Randomization was done using computer-generated randomized numbers. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical University Innsbruck.

Surgical technique

All operations were performed under general anesthesia.

TEP

TEP was performed with a single-use blunt trocar and with two reusable 5 mm trocars. An infraumbilical incision was made and the ipsilateral anterior rectus sheath was opened. A blunt digital dissection of the preperitoneal space posterior to the ipsilateral rectus muscle was performed. A blunt trocar with CO2 insufflation and a 0° laparoscope were introduced in the preperitoneal space. Two 5 mm trocars were then introduced suprapubically in the midline position and laterally cranial to the anterior superior iliac spine, respectively. The hernia sac was retracted and a 10 × 15 cm polypropylene mesh (Parietex® Polyester Mesh, Covidien, Vienna, Austria) was positioned at the groin area covering the inguinal fossae without additional fixation. The CO2 was exsufflated and the anterior rectus sheath was closed with 2-0 polyglactin interrupted sutures (Vicryl, Ethicon GmbH, Vienna, Austria). The skin was closed with a stapler.

Plug and patch (PP)

The mesh-plug technique was performed as described by Rutkow and Robbins [5] using a Bard Mesh Perfix plug (monofilament knitted polypropylene; Davol Inc., Cranston, RI). The plug was fixed with 3–4 single sutures with 2-0 polyglactin (Vicryl, Ethicon GmbH, Vienna, Austria) and the patch was positioned in a sublay technique without additional fixation. After closure of the external oblique fascia with 2-0 polyglactin interrupted sutures (Vicryl, Ethicon GmbH, Vienna, Austria) the skin was closed with a stapler.

Postoperative care

All patients received standard pain medication: paracetamol 500 mg twice daily and piritramid 7.5 mg s.c. at numerical rating scale (NRS) ≥ 3 (0–10) on the day of surgery and on demand further on. Consumption of pain medication (paracetamol 500 mg) was recorded in the study protocol.

Perioperative pain assessment

Pain was recorded using the Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ) comprising the numerical rating scale (NRS, 0–10; 0 = no pain, 10 = worst possible pain) before randomization (preoperatively), at 6, 12 and 24 months after surgery, a verbal rating scale (VRS) to assess the individual pain intensity at present (0–5; 0 = no pain, 1 = mild, 2 = discomforting, 3 = distressing, 4 = horrible, 5 = excruciating) and a scale to assess the quality of pain. All patients received the same postoperative instructions (limitation on heavy weight lifting for 4 weeks) and were encouraged to return to work and normal activities as soon as possible.

Follow-up

Four-week pain diaries were handled to the patients at hospital admission containing NRS four times a day (morning, noon, afternoon, evening) with an extra section for recording additional analgesia in the follow-up. At return of the diaries, patients underwent a physical examination in the outpatients clinic. Long-term follow-up was carried out by an independent study assistant (C.K.) and a pain specialist (A.S.). An independent surgeon in the out-patient clinic saw patients with any complaints and recurrence was defined as a bulge in the operative area necessitating further operation.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using SPSS 18.0 software for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Baseline characteristics are shown using median and range for continuous variables and relative and absolute frequencies for categorical variables. Mann–Whitney U test and Chi-square test were applied to test for significant baseline differences. Mann–Whitney U test with Bonferroni correction was used to assess differences in analgetics use and pain ratings. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

During the observational period (March 2005–September 2009) 1.174 patients with an inguinal hernia were operated upon. A total of 154 male patients was randomized to undergo TEP (n = 77) or PP (n = 77). Eighty-nine patients (54.9 %) were followed up 24 months (see CONSORT diagram, Table 3). Median follow-up in the TEP group was 3.82 years (IQR 2.93–4.8) and 3.85 in the PP group (IQR 3.02–5.21) (p = 0.384).

Median duration of hospital stay was 4 days in each group. Median operating time under TEP was significantly longer (61 vs. 56 min; p = 0.038). Recurrence was only observed in one patient in the TEP group (1.3 %) and in two patients in the PP group (2.6 %) without any significant differences between the groups (p = 0.56). Early postoperative complications are illustrated in Table 4 and did not differ significantly between the two groups (p = 0.456). Analgesic usage was similar in both groups during the first three postoperative days with mean 500 mg paracetamol orally twice daily and one subcutaneous injection of 7.5 mg piritramid on demand (p > 0.05). On postoperative day four and five significantly more patients in the PP group demanded acute analgesic medication (piritramid 7.5 mg s.c. 9.1 vs. 1.3 % on postoperative day four and 7.8 vs. 0 % on postoperative day five, p = 0.031 and p = 0.013, respectively). No significant differences were observed in the SF-MPQ regarding sensory and affective dimensions of pain experience between TEP and PP preoperatively, 6, 12 and 24 months postoperatively (data not shown). The NRS did not show any significant differences between the TEP and the PP group neither in the preoperative period (median 1.2 [IQR 0–3.2] and 1.0 [IQR 0–3.2], p = 0.954, respectively) nor in the long-term follow-up as observed for the VRS (Table 5).

Evaluation of the 4-week pain diaries revealed significant differences especially from end of postoperative week two between both groups favoring the TEP group regarding NRS (Fig. 1).

Discussion

Currently, mesh-based groin hernia repair is the gold standard, either in the open or endoscopic/laparoscopic approach. Our data demonstrate that significant differences in postoperative pain (NRS) assessed by 4-week pain diaries only exist from postoperative week two between the minimally invasive TEP and the open PP technique regarding primary unilateral groin hernia repair (p < 0.05, Fig. 1). However, the difference, although significantly different, has no obvious clinical relevance (NRS 0–1). Chronic pain has a multifactorial etiology and may develop despite careful handling of nerves and meticulous surgical technique [7]. Prevention of chronic pain by prophylactic resection of the ilioinguinal nerve does not reduce the risk of chronic pain after open hernia surgery [8]. In this study the ilioinguinal nerve was therefore routinely preserved. Moreover, identification of all inguinal nerves during open hernia surgery may reduce the risk of nerve damage and postoperative chronic groin pain.

The major shortcoming of this prospective randomized-controlled single-center trial is the high rate of lost to follow-up patients in the study cohort after 24 months (45.1 %). Patients were contacted by a cover letter in terms of repeated unavailability on the phone. Systematic reviews have shown that several studies with an incomplete follow-up of less than 80 % of patients might explain the wide range in incidences of postoperative pain [2]. Liem et al. [9] favor the laparoscopic technique regarding incidence of chronic inguinal pain in a large series (2 vs. 14 %, p < 0.001), however, the difference in the rates of recurrence between the two groups was similar (p = 0.05).

Chronic pain is defined as any pain reported by the patient at or beyond 3 months postoperatively, as per the International Association of the Study of Pain [10]. Interestingly, the incidence of postoperative pain strongly depends on the method of pain assessment in the follow-up. Nienhuijs et al. [2] could clearly demonstrate that the incidence of chronic pain was much higher (to 40 %) in the studies using either the visual analog or the verbal descriptor scale than a simple questionnaire. In our study, we used the above mentioned scores to assess postoperative pain. However, chronic pain at the 2-year follow-up was zero (median NRS) in both groups and not significantly different between both groups (p = 0.428). Although the TEP procedure took significantly longer than the PP method, concerning duration of hospital stay and early complications, we do not consider operating time to have clinical relevance. Major drawback of this trial was the low return rate of pain diaries due to postal problems or patients incompliance (60.5 %).

While other studies report rates of chronic inguinal pain up to 40 % [11, 12] following open as well as laparoscopic hernia repair in the long-term follow-up, chronic pain was not a serious problem in our cohort.

Taking into account the professional occupation of our patients, about 20 % hold down a job with heavy physical stress (19 % in the TEP and 25.3 % in the PP group). This might be an important preoperative consideration when choosing the appropriate method for these patients. Other factors mentioned in the literature to be associated with chronic pain such as gender, activity level, and mental state were not found to influence the prevalence of chronic pain [2]. Also, insufficient data were available to determine the influence of surgical expertise of the institute or the operating team. In our study, a high number of different surgeons in different training status performed the operations in an academic institution, however under supervision/assistance of an experienced general surgeon.

The rate of chronic pain depends on the method of pain assessment. Nienhuijs et al. found that in studies using a questionnaire for assessing postoperative pain following groin hernia repair fewer patients were found to have chronic pain (OR 0.55, p < 0.001). The instrument for pain measurement remained the strongest factor influencing pain in the multivariate analysis (OR 0.51, p < 0.001) [2].

Regarding recurrence rate we could not find any significant differences between the open and the laparoscopic technique, however, meta-analyses derived a trend toward an increase in the relative odds of recurrence after laparoscopic repair [13]. Sharing the opinion of other authors that early recurrence rates in laparoscopic groin hernia repair are closely related to the surgeons’ expertise [9], the TEP procedures in our center were performed by surgeons who were experienced in this technique or were supervised by an experienced surgeon. The recurrences in the PP group occured in the long-term follow-up. The difference in recurrence rates in open and laparoscopic study groups can therefore be expected to increase over time and early recurrence rates are expected to be caused by technical errors [9].

To summarize, minimally invasive techniques like the TEP procedure improve for lower postoperative pain following groin hernia repair. Early complication and recurrence rates are low and do not differ between open, tension-free mesh plasty (PP) and TEP procedure. Pain questionnaires and diaries are still gold standard for assessing pain qualities and intensity following groin hernia repair.

References

Pavlids TE (2010) Current opinion on laparoscopic repair of inguinal hernia. Surg Endosc 24:974–976

Nienhuijs S, Staal E, Strobbe L, Rosman C, Groenewoud H, Bleichrodt R (2007) Chronic pain after mesh repair of inguinal hernia: a systematic review. Am J Surg 194(3):394–400

Singh AN, Bansal VK, Misra MC, Kumar S, Rajeshwari S, Kumar A, Sagar R, Kumar A (2012) Testicular functions, chronic groin pain, and quality of life after laparoscopic and open mesh repair of inguinal hernia: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Surg Endosc 26(5):1304–1317

Kugel RD (1999) Minimally invasive, nonlaparoscopic, preperitoneal, and sutureless, inguinal herniorrhaphy. Am J Surg 178:298–302

Rutkow IM, Robbins AW (1993) “Tension-free” inguinal herniorrhaphy: a preliminary report on the “mesh plug” technique. Surgery 114:3–8

Nyhus LM (1993) Individualization of hernia repair: a new era. Surgery 114:1–2

Alfieri S, Amid PK, Campanelli G, Izard G, Kehlet H, Wijsmuller AR, Di Miceli D, Doglietto GB (2011) International guidelines for prevention and management of post-operative chronic pain following inguinal hernia surgery. Hernia 15(3):239–249

Simons MP, Aufenacker T, Bay-Nielsen M, Bouillot JL, Campanelli G, Conze J, de Lange D, Fortelny R, Heikkinen T, Kingsnorth A, Kukleta J, Morales-Conde S, Nordin P, Schumpelick V, Smedberg S, Smietanski M, Weber G, Miserez M (2009) European Hernia Society guidelines on the treatment of inguinal hernia in adult patients. Hernia 13:343–403

Liem MS, van der Graaf Y, van Steensel CJ, Boelhouwer RU, Clevers GJ, Meijer WS, Stassen LP, Vente JP, Weidema WF, Schrijvers AJ, van Vroonhoven TJ (1997) Comparison of conventional anterior surgery and laparoscopic surgery for inguinal-hernia repair. N Engl J Med 336(22):1541–1547

Merskey H, Bogduk N (1994) Classification of chronic pain: descriptions of chronic pain syndromes and definitions of pain terms. In: Merskey H, Bogduk N (eds) Task force on taxonomy of the IASP, 2nd edn. IASP Press, Seattle, pp 209–214

Muldoon RL, Marchant K, Johnson DD, Yoder GG, Read RC, Hauer-Jensen M (2004) Lichtenstein vs anterior preperitoneal prosthetic mesh placement in open inguinal hernia repair: a prospective, randomized trial. Hernia 8(2):98–103

Nienhuijs SW, Boelens OB, Strobbe LJ (2005) Pain after anterior mesh hernia repair. J Am Coll Surg 200:885–889

Memon MA, Cooper NJ, Memon B, Memon MI, Abrams KR (2003) Meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials comparing open and laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. Br J Surg 90(12):1479–1492

Conflict of interest

FA, FA, CK, AS, HU, JP and TS declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical standard

The authors declare that the trial complies with the current laws of Austria.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

F. Aigner and F. Augustin shared first authorship.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Aigner, F., Augustin, F., Kaufmann, C. et al. Prospective, randomized-controlled trial comparing postoperative pain after plug and patch open repair with totally extraperitoneal inguinal hernia repair. Hernia 18, 237–242 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-013-1123-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-013-1123-6