Abstract

We report on a new method for the repair of spigelian hernia, in which we combined the step-by-step local anesthesia and open preperitoneal mesh repair techniques. After initial infiltration of local anesthetics, we incised the attenuated fascia and slightly enlarged the fascial defect to facilitate easy return of hernial content into the abdominal cavity. We injected preperitoneally, in a radial fashion around the peritoneal sac, more saline solution, consisting of 1:200,000 epinephrine (g:g) and ⅓ bupivacain (v:v). We dissected the peritoneum away from the anterior abdominal wall to create a preperitoneal pocket of sufficient size. We spread open a 9×9-cm polypropylene mesh in the area, as if we were doing a GPRVS of Stoppa. We followed up our four patients for an average of 32 months. All four cases had an uneventful recovery and were discharged in an average of 3.5 days. They returned to normal daily activity on the 9th day after surgery. We suggest that the preperitoneal mesh repair of a spigelian hernia under local anesthesia is a simple and feasible technique with favorable early and late postoperative results and deserves further investigation in larger series.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The spigelian hernia is a rare kind of abdominal wall defect that has been treated using a variety of techniques. When it is considered, the diagnosis is not as difficult as it had once been thought [1, 2]. The condition requires a surgical repair because of its high risk of complications [3, 4]. Aside from its conventional repair by direct approximation of the neighboring muscular tissues, some alternative open mesh and laparoscopic modalities of repair have been reported in recent years [5, 6, 7]. Could the concept of open posterior preperitoneal repair technique that has been successfully used in inguinal and some ventral hernias be applied to the repair of spigelian hernia defects with favorable early and late results [8, 9]? We, herewith, report on four patients in whom we repaired the spigelian hernia defects by an open preperitoneal tension-free technique under local anesthesia. A separate author who has followed up our patients for an average of 32 months determined the surgical results and patients' compliance.

Patients and methods

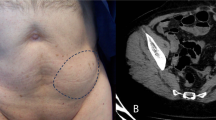

There were two males and two females whose ages ranged from 42–67 years (Table 1). All four patients referred with pain, and three reported a lump at the site of hernia. Case #2 has had chronic renal failure and was under continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) program at the time of diagnosis. An incarcerated spigelian hernia was diagnosed in Case #3 when she was hospitalized for an extensive aortic aneurysm that had extensions to both common iliac arteries. We found a lump at the site of spigelian hernia during initial physical examination in all four cases. We confirmed the presence of hernia by an ultrasound in three cases, and by a CT scan in two (Fig. 1). We suspected long-term elevated intra-abdominal pressure in cases #2 and #4, in whom the abdominal wall exhibited a general muscular weakness. After definite preoperative diagnosis of spigelian hernias, we accomplished an open preperitoneal mesh repair under local anesthesia in all four cases.

Surgical technique

We applied local anesthesia in a three-step fashion, as adapted from that of Amid et al. [10]. For this purpose, we used 65 ml (range 40–90 ml) of saline solution including 1:3 bupivacaine (v:v) and 1/200,000 adrenaline (g:g). We initially aimed for blockage of the skin and subcutaneous tissue, after which we started with a short transverse incision centered over the bulging. As we reached the bulging attenuated spigelian aponeurosis, we infiltrated a generous amount of local anesthetics into the aponeurotic layers around the bulging and into the surrounding muscular tissue. After this second step of infiltration, we incised the attenuated fascia around the neck of the bulging to expose the hernia sac, slightly enlarged the defect (if necessary) by cutting the fascia at medial and lateral sides, and peeled off a narrow segment of peritoneum in a circular fashion. Through this opening, we infiltrated local anesthetic solution radially into the preperitoneal space, utilizing a high-pressure jet technique by a disposable 25G spinal needle. This maneuver helped in better dissection of the peritoneum, which is normally strongly fused to an underlying layer at this part of the abdominal wall. As we formed a preperitoneal pouch of sufficient size by sharp and finger dissection, we laid open a 9×9 cm polypropylene mesh (Prolene, Ethicon Ltd., U.K.) in the area in a fashion mimicking that of Stoppa [11] (Fig. 2). We asked the patient to cough while we checked how the mesh fit into the space and how well it held the hernia back. We did not fixate the mesh in place and did not drain the wound. We approximated the external oblique aponeurosis and the subcutaneous tissue with several sparsely placed absorbable sutures. The skin was brought together using staples.

Follow-up

Each patient was asked to determine his (or her) postoperative pain by using McGill's Pain Score Scale on the 1st, 7th, and 30th postoperative days (pod) and at 6 months [12]. By filling out this questionnaire, each patient quantified his (or her) pain using the verbal rating scale [0 (no pain) to 5 (excruciating pain)] (Table 2). Early pain scores were attributed to surgery, while pain at 6 months was considered to be related to a previous condition. All the patients received a routine intramuscular dose of 75 mg diclophenac sodium on the evening of the operation day. Thereafter, patients were instructed to take tablets of the same drug as necessary. Total analgesic consumption in the first week was recorded on the 7th pod. We did not restrict the physical activity postoperatively. One of the authors carried out the long-term follow-up on an outpatient basis, or requested the completion and return of a written questionnaire from those who did not show up. The length of hospital stay, time to return to pain-free daily activity, postoperative complications, and patients' satisfaction with the operation were recorded [8]. We performed no statistical analysis.

Discussion

The conventional repair technique of spigelian hernia depends on direct tissue approximation; however, such a repair causes variable degrees of tension that results in postoperative pain, local necrosis, and suture line failure, following with recurrence. There are reports that describe recurrence after conventional repair of spigelian hernias [13, 14].

Sanchez-Montes and Deysine [5] reported their method for the repair of a spigelian hernia utilizing a preshaped polypropylene umbrella plug. Their description of the technique and the material strongly suggested that a small- to a medium-size direct inguinal hernia was to be repaired by a plug [15]. However, the anatomic structures at this level of the abdominal wall are not the same as those of the inguinal region. Namely, the preperitoneal space is not that voluminous, the peritoneum is strongly adherent to underlying tissue, and the intra-abdominal organs come in close contact with the posterior surface of the abdominal wall during straining. As depicted in the original paper, the umbrella mesh used in a spigelian hernia would most probably bulge into the abdominal cavity, a fact that would eventually cause its intraperitoneal migration and fistula formation. Larger defects, like the one in our first case, would not be suitable for plugging, as well. Shulman et al. [16] did not recommend plug repair of inguinal or femoral defects larger than 3.5 cm. We believe that validity of plug repair needs to be confirmed by long-term results.

There are increasing numbers of reports advocating laparoscopic repair of spigelian hernias [2, 6, 7, 17]. Laparoscopic repair of a spigelian hernia may be a viable option in certain conditions. This technique is very suitable in those patients who have additional intraperitoneal pathologies to be resolved by the use of laparoscopy (e.g. cholecystolithiasis, inguinal hernia) [18, 19, 20]. In their retrospective series of 81 cases, Larson and Farley [13] reported that a second procedure accompanied repair of spigelian hernia in 12 patients. With the growing use of laparoscopy, it seems likely that more spigelian hernias will be diagnosed coincidentally during other intra-abdominal procedures and repaired per se [18]. Laparoscopy seems to be a perfect diagnostic measure in those patients in whom the diagnosis of a spigelian hernia is controversial [21]. However, there are two major drawbacks of laparoscopic repair of a spigelian hernia. First, it requires general or spinal anesthesia, a fact that is crucial in elderly and debilitated patients. Second, some measures are to be taken to prevent the intra-abdominal structures from adhering to the intraperitoneally placed mesh material [6]. Innovative composite mesh materials and ePTFE have facilitated laparoscopic repair of ventral and spigelian hernias by intraperitoneally placed mesh [18, 22, 23]. Moreno-Egea et al. [2, 7] obtained favorable results with totally extraperitoneal laparoscopic repair of spigelian hernias and advocated its use as a technique of choice in uncomplicated cases.

Our open preperitoneal mesh repair technique under local anesthesia was simple and yielded good clinical results. Our 50-min operating time and only one incidence of postoperative seroma collection was better than those of the conventional group and corresponds well with laparoscopic results of Moreno-Egea's series [7]. An average hospital stay of 3.5 days falls in between the associated figures of Moreno's conventional and laparoscopic groups, as well. Our 9-day average of return to normal daily activity corresponds with those reported for unilateral inguinal hernias [24] and is shorter than figures for bilateral inguinal hernias [8]. The low pain scores and willingness to have the same operation again show favorable patient compliance to the surgical and anesthesia techniques used.

We conclude that preperitoneal mesh repair of a spigelian hernia under local anesthesia seems to be a simple and reliable method and is well tolerated by patients. However, its feasibility as an alternative method to either conventional or laparoscopic techniques is to be warranted by larger series.

References

Losanoff JE, Richman BW, Jones JW (2002) Spigelian hernia in a child: case report and review of the literature. Hernia 6:191–193

Moreno-Egea A, Flores B, Girela E, Martin JG, Aguayo JL, Canteras M (2002) Spigelian hernia: bibliographical study and presentation of a series of 28 patients. Hernia 6:167–170

Rogers FB, Camp PC (2001) A strangulated Spigelian hernia mimicking diverticulitis. Hernia 5:51–52

Nursal TZ, Kologlu M, Aran O (1997) Spigelian hernia presenting as an incarcerated incisional hernia. Hernia 1:149–150

Sanchez-Montes I, Deysine M (1998) A new repair technique using preshaped polypropylene umbrella plugs. Arch Surg 133:670–672

Fisher BL (1994) Video-assisted Spigelian hernia repair. Surg Laparosc Endosc 4:238–240

Moreno-Egea A, Carrasco L, Girela E, Martin JG, Aguayo JL, Canteras M (2002) Open vs laparoscopic repair of spigelian hernia. Arch Surg 137:1266–1268

Malazgirt Z, Ozkan K, Dervisoglu A, Kaya E (2000) Comparison of Stoppa and Lichtenstein techniques in the repair of bilateral inguinal hernias. Hernia 4:264–267

Solorzano CC, Minter RM, Childers TC, Kilkenny JW, Vauthey JN (1999) Prospective evaluation of the giant prosthetic reinforcement of the visceral sac for recurrent and complex bilateral inguinal hernias. Am J Surg 177:19–22

Amid PK, Shulman AG, Lichtenstein IL (1994) Local anesthesia for inguinal hernia repair step-by-step procedure. Ann Surg 220:735–737

Stoppa R (1995) The preperitoneal approach and prosthetic repair of groin hernias. In: Nyhus LM, Condon RE (eds) Hernia J.B.Lippincott, Philadelphia, pp 188–210

Melzack R (1987) The short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire. Pain 30:191–197

Larson DW, Farley DR (2002) Spigelian hernias: repair and outcome for 81 patients. World J Surg 26:1277–1281

Losanoff JE, Jones JW, Richman BW (2001) Recurrent Spigelian hernia: a rare cause of colonic obstruction. Hernia 5:101–104

Rutkow IM, Robbins AW (1993) ''Tension-free" inguinal herniorrhaphy: a preliminary report on the "mesh plug" technique. Surgery 144:3–8

Shulman AG, Amid PK, Lichtenstein IL (1994) Patch or plug for groin hernia-which? Am J Surg 167:331–336

Kasirajan K, Lopez J, Lopez R (1997) Laparoscopic technique in the management of Spigelian hernia. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 7:385–388

DeMatteo RP, Morris JP, Broderick G (1994) Incidental laparoscopic repair of a spigelian hernia. Surgery 115:521–522

Amendolora M (1998) Videolaparoscopic treatment of spigelian hernias. Surg Laparosc Endosc 8:136–139

Gedebou TM, Neubauer W (1998) Laparoscopic repair of bilateral spigelian and inguinal hernias. Surg Endosc 12:1424–1425

Carter JE, Mizes C (1992) Laparoscopic diagnosis and repair of spigelian hernia: report of a case and technique. Am J Obstet Gynecol 167:77–78

Barie PS (1994) Planned laparoscopic repair of a spigelian hernia using a composite prosthesis. J Laparoendosc Surg 4: 359–363

Goodney PP, Birkmeyer CM, Birkmeyer JD (2002) Short-term outcomes of laparoscopic and open ventral hernia repair: a meta-analysis. Arch Surg 137:1161–1165

Liem MS, van der Graaf Y, Zwart RC, Geurts I, van Vroonhoven TJ (1997) A randomized comparison of physical performance following laparoscopic and open inguinal hernia repair. Br J Surg 84:64–67

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Malazgirt, Z., Dervisoğlu, A., Polat, C. et al. Preperitoneal mesh repair of spigelian hernias under local anesthesia: description and clinical evaluation of a new technique. Hernia 7, 202–205 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-003-0153-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-003-0153-x